Tailoring Truтʜ

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bangor University DOCTOR of PHILOSOPHY Reimagining

Bangor University DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Reimagining Everyday Life in the GDR Post-Ostalgia in Contemporary German Films and Museums Kreibich, Stefanie Award date: 2019 Awarding institution: Bangor University Link to publication General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 29. Sep. 2021 Reimagining Everyday Life in the GDR: Post-Ostalgia in Contemporary German Films and Museums Stefanie Kreibich Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of PhD in Modern Languages Bangor University, School of Modern Languages and Cultures April 2018 Abstract In the last decade, everyday life in the GDR has undergone a mnemonic reappraisal following the Fortschreibung der Gedenkstättenkonzeption des Bundes in 2008. No longer a source of unreflective nostalgia for reactionaries, it is now being represented as a more nuanced entity that reflects the complexities of socialist society. The black and white narratives that shaped cultural memory of the GDR during the first fifteen years after the Wende have largely been replaced by more complicated tones of grey. -

Überseehafen Rostock: East Germany’S Window to the World Under Stasi Watch, 1961-1989

Tomasz Blusiewicz Überseehafen Rostock: East Germany’s Window to the World under Stasi Watch, 1961-1989 Draft: Please do not cite Dear colleagues, Thank you for your interest in my dissertation chapter. Please see my dissertation outline to get a sense of how it is going to fit within the larger project, which also includes Poland and the Soviet Union, if you're curious. This is of course early work in progress. I apologize in advance for the chapter's messy character, sloppy editing, typos, errors, provisional footnotes, etc,. Still, I hope I've managed to reanimate my prose to an edible condition. I am looking forward to hearing your thoughts. Tomasz I. Introduction Alexander Schalck-Golodkowski, a Stasi Oberst in besonderen Einsatz , a colonel in special capacity, passed away on June 21, 2015. He was 83 years old. Schalck -- as he was usually called by his subordinates -- spent most of the last quarter-century in an insulated Bavarian mountain retreat, his career being all over three weeks after the fall of the Wall. But his death did not pass unnoticed. All major German evening TV news services marked his death, most with a few minutes of extended commentary. The most popular one, Tagesschau , painted a picture of his life in colors appropriately dark for one of the most influential and enigmatic figures of the Honecker regime. True, Mielke or Honecker usually had the last word, yet Schalck's aura of power appears unparalleled precisely because the strings he pulled remained almost always behind the scenes. "One never saw his face at the time. -

The Art of Society, 1900-1945: the Nationalgalerie Collection 1 / 23 1

The Art of Society, 1900-1945: The Nationalgalerie Collection 1 / 23 1. Tarsila do Amaral Long-term loan from the Fundação José Distance, 1928 e Paulina Nemirovsky to the Pinacoteca Oil on canvas do Estado de São Paulo 65 × 74.5 cm 2. Alexander Archipenko Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Flat Torso, 1914 (cast, late 1950s) Nationalgalerie Bronze Acquired in 1965 from the Galerie 48 x 10,5 x 10,5 cm (base included) Grosshennig, Düsseldorf, by the Land Berlin for the Galerie des 20. Jahrhunderts, Berlin (West) 3. Alexander Archipenko Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Woman Standing, 1921 Nationalgalerie Bronze Acquired in 1977 from the 67,5 x 14,5 x 15 cm Handelsorganisation (HO) Cottbusser Börse, Cottbus, for the Nationalgalerie, Berlin (East) 4. Hans Arp Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Constellation (Shellhead and Tie), Nationalgalerie 1928 Gift from the Ulla and Heiner Pietzsch Wood, 25,1 x 33,9 x 6 cm Collection to the Land Berlin, 2010 5. Hans Arp Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Sitting, 1937 Nationalgalerie Limestone Gift from the Ulla and Heiner Pietzsch 29,5 x 44,5 x 18 cm Collection to the Land Berlin, 2010 6. Hans Arp Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Concrete Relief, 1916/1923 Nationalgalerie Wood Acquired in 1979 from the estate of 21,4 x 27,7 x 7 cm Hannah Höch, Berlin, by the Freunde der Nationalgalerie for the Nationalgalerie, Berlin (West) 7. Hans Arp Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Concretes Relief, 1916/1917 Nationalgalerie Wood Acquired in 1979 from the estate of 41,2 x 60,6 x 12 cm Hannah Höch, Berlin, by the Freunde der Nationalgalerie for the Nationalgalerie, Berlin (West) 8. -

Plenarprotokoll 15/56

Plenarprotokoll 15/56 Deutscher Bundestag Stenografischer Bericht 56. Sitzung Berlin, Donnerstag, den 3. Juli 2003 Inhalt: Begrüßung des Marschall des Sejm der Repu- rung als Brücke in die Steuerehr- blik Polen, Herrn Marek Borowski . 4621 C lichkeit (Drucksache 15/470) . 4583 A Begrüßung des Mitgliedes der Europäischen Kommission, Herrn Günter Verheugen . 4621 D in Verbindung mit Begrüßung des neuen Abgeordneten Michael Kauch . 4581 A Benennung des Abgeordneten Rainder Tagesordnungspunkt 19: Steenblock als stellvertretendes Mitglied im a) Antrag der Abgeordneten Dr. Michael Programmbeirat für die Sonderpostwert- Meister, Friedrich Merz, weiterer Ab- zeichen . 4581 B geordneter und der Fraktion der CDU/ Nachträgliche Ausschussüberweisung . 4582 D CSU: Steuern: Niedriger – Einfa- cher – Gerechter Erweiterung der Tagesordnung . 4581 B (Drucksache 15/1231) . 4583 A b) Antrag der Abgeordneten Dr. Hermann Zusatztagesordnungspunkt 1: Otto Solms, Dr. Andreas Pinkwart, weiterer Abgeordneter und der Fraktion Abgabe einer Erklärung durch den Bun- der FDP: Steuersenkung vorziehen deskanzler: Deutschland bewegt sich – (Drucksache 15/1221) . 4583 B mehr Dynamik für Wachstum und Be- schäftigung 4583 A Gerhard Schröder, Bundeskanzler . 4583 C Dr. Angela Merkel CDU/CSU . 4587 D in Verbindung mit Franz Müntefering SPD . 4592 D Dr. Guido Westerwelle FDP . 4596 D Tagesordnungspunkt 7: Krista Sager BÜNDNIS 90/ a) Erste Beratung des von den Fraktionen DIE GRÜNEN . 4600 A der SPD und des BÜNDNISSES 90/ DIE GRÜNEN eingebrachten Ent- Dr. Guido Westerwelle FDP . 4603 B wurfs eines Gesetzes zur Förderung Krista Sager BÜNDNIS 90/ der Steuerehrlichkeit DIE GRÜNEN . 4603 C (Drucksache 15/1309) . 4583 A Michael Glos CDU/CSU . 4603 D b) Erste Beratung des von den Abgeord- neten Dr. Hermann Otto Solms, Hubertus Heil SPD . -

Deutscher Bundestag Gesetzentwurf

Deutscher Bundestag Drucksache 14/533 14. Wahlperiode 16. 03. 99 Gesetzentwurf der Abgeordneten Dr. Peter Struck, Otto Schily, Wilhelm Schmidt (Salzgitter), Kerstin Müller (Köln), Rezzo Schlauch, Kristin Heyne, Dr. Wolfgang Gerhardt, Dr. Guido Westerwelle, Jörg van Essen, Dieter Wiefelspütz, Ludwig Stiegler, Marieluise Beck (Bremen), Cem Özdemir, Rainer Brüderle Brigitte Adler, Gerd Andres, Rainer Arnold, Hermann Bachmaier, Ernst Bahr, Doris Barnett, Dr. Hans Peter Bartels, Ingrid Becker-Inglau, Wolfgang Behrendt, Dr. Axel Berg, Hans-Werner Bertl, Friedhelm Julius Beucher, Petra Bierwirth, Rudolf Bindig, Lothar Binding (Heidelberg), Klaus Brandner, Willi Brase, Dr. Eberhard Brecht, Rainer Brinkmann (Detmold), Bernhard Brinkmann (Hildesheim), Hans-Günter Bruckmann, Hans Büttner (Ingolstadt), Dr. Michael Bürsch, Ursula Burchardt, Hans Martin Bury, Marion Caspers-Merk, Wolf-Michael Catenhusen, Dr. Herta Däubler-Gmelin, Dr. Peter Wilhelm Danckert, Christel Deichmann, Rudolf Dreßler, Detlef Dzembritzki, Dieter Dzewas, Sebastian Edathy, Marga Elser, Peter Enders, Gernot Erler, Petra Ernstberger, Annette Faße, Lothar Fischer (Homburg), Gabriele Fograscher, Iris Follak, Norbert Formanski, Rainer Fornahl, Dagmar Freitag, Peter Friedrich (Altenburg), Lilo Friedrich (Mettmann), Harald Friese, Anke Fuchs (Köln), Arne Fuhrmann, Iris Gleicke, Günter Gloser, Uwe Göllner, Renate Gradistanac, Günter Graf (Friesoythe), Dieter Grasedieck,Wolfgang Grotthaus, Karl-Hermann Haack (Extertal), Hans-Joachim Hacker, Klaus Hagemann, Manfred Hampel, Alfred Hartenbach, -

Politikszene 5.4

politik & Ausgabe Nr. 86 kommunikation politikszene 5.4. – 11.4.2006 Doppler neu bei CNC Heinrich Doppler (59) ist neuer Partner der Communications & Network Consulting AG (CNC) in Berlin. Ab Juli wird er zudem in die Berliner Geschäftsleitung des Beratungsunternehmens eintreten. Dopp- ler war zuletzt Staatsrat in der Hamburger Umweltbehörde, die er im Februar verließ (politikszene 74 brich- tete). Davor war er bereits Staatsrat in der Behörde für Wirtschaft und Arbeit der Hansestadt. Von 1995 bis 2003 war er in verschiedenen Positionen für das Elektrotechnik-Unternehmen ABB in Bonn und Berlin tätig. Heinrich Doppler DKG: Baum folgt auf Robbers Georg Baum (50) ist neuer Hauptgeschäftsführer der Deutschen Krankenhausgesellschaft (DKG). Er tritt die Nachfolge von Jörg Robbers (65) an, der in Ruhestand ging. Der Diplom-Volkswirt Baum leitete seit 1993 die Unterabteilung „Gesundheitsversorgung und Krankenhauswesen“ im Bundesgesund- heitsministerium (BMGS). Zuvor war er Leiter der BMGS-Unterabteilung „Grundsatz- und Planungsangelegen- heiten, Öffentlichkeitsarbeit“ und Leiter des Bonner Büros des Bundesverbandes der Betriebskassen. Georg Baum Pleon: Hauptstadtbüro mit neuer Leitung Christiane Schulz (37) und Cornelius Winter (32) übernehmen ab Mai die Leitung des Berliner Büros von Pleon. Sie lösen Jörg Ihlau (43) ab, der künf- tig andere Aufgaben innerhalb der deutschen Pleon-Gruppe übernehmen wird. Schulz arbeitete zuletzt als Business Director für zentrale Key-Accounts in der Düsseldorfer Zentrale der PR-Agenturgruppe und lenkte die europäische -

Strengthening Transatlantic Dialogue 2019 Annual Report Making Table of an Impact Contents

STRENGTHENING TRANSATLANTIC DIALOGUE 2019 ANNUAL REPORT MAKING TABLE OF AN IMPACT CONTENTS THE AMERICAN COUNCIL 01 A Message from the President ON GERMANY WAS INCORPORATED IN 1952 POLICY PROGRAMS in New York as a private, nonpartisan 02 2019 Event Highlights nonprofit organization to promote 05 German-American Conference reconciliation and understanding between Germans and Americans 06 Eric M. Warburg Chapters in the aftermath of World War II. 08 Deutschlandjahr USA 2018/2019 PROGRAMS FOR THE SUCCESSOR GENERATION THE ACG HELD MORE THAN 140 EVENTS IN 2019, 10 American-German Young Leaders Program addressing topics from security 13 Fellowships policy to trade relations and from 14 Study Tours technology to urban development. PARTNERS IN PROMOTING TRANSATLANTIC COOPERATION SINCE THEIR INCEPTION 16 John J. McCloy Awards Dinner IN 1992, THE NUMBER OF 18 Corporate Membership Program ERIC M. WARBURG Corporate and Foundation Support CHAPTERS HAS GROWN TO 22 IN 18 STATES. 19 Co-Sponsors and Collaborating Organizations In 2019, the ACG also was Individual Support active in more than 15 additional communities. ABOUT THE ACG 20 The ACG and Its Mission 21 Officers, Directors, and Staff MORE THAN 100 INDIVIDUALS PARTICIPATED IN AN IMMERSIVE EXCHANGE EXPERIENCE through programs such as the American-German Young Leaders Conference, study tours, and fact-finding missions in 2019. More than 1,100 rising stars have VISION participated in the Young Leaders program since its launch in 1973. The American Council on Germany (ACG) is the leading U.S.-based forum for strengthening German-American relations. It delivers a deep MORE THAN 1,100 and nuanced understanding of why Germany INDIVIDUALS HAVE matters, because the only way to understand TRAVELED ACROSS THE ATLANTIC contemporary Europe is to understand Germany’s since 1976 to broaden their personal role within Europe and around the world. -

Revue Des Études Slaves, LXXXVI-1-2

Revue des études slaves LXXXVI-1-2 | 2015 Villes postsocialistes entre rupture, evolutioń et nostalgie Andreas Schönle (dir.) Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/res/629 DOI : 10.4000/res.629 ISSN : 2117-718X Éditeur Institut d'études slaves Édition imprimée Date de publication : 15 septembre 2015 ISBN : 978-2-7204-0537-2 ISSN : 0080-2557 Référence électronique Andreas Schönle (dir.), Revue des études slaves, LXXXVI-1-2 | 2015, « Villes postsocialistes entre rupture, évolution et nostalgie » [En ligne], mis en ligne le 26 mars 2018, consulté le 23 septembre 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/res/629 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/res.629 Ce document a été généré automatiquement le 23 septembre 2020. Revue des études slaves 1 SOMMAIRE Introduction. Les défis de la condition post-postsocialiste Architecture et histoire en Europe centrale et orientale Andreas Schönle Traitement du patrimoine ‘Scientific Reconstruction’ or ‘New Oldbuild’? The Dilemmas of Restoration in Post-Soviet St. Petersburg Catriona Kelly Beyond Preservation: Post-Soviet Reconstructions of the Strelna and Tsaritsyno Palace- Parks Julie Buckler Московское зарядье: затянувшееся противостояние города и градостроителей Аleksandr Možaev Les monuments étrangers : la mémoire des régimes passés dans les villes postsocialistes Marina Dmitrieva Reconfiguration urbaine Olympian Plans and Ruins: the Makeover of Sochi William Nickell Perm′, laboratoire de la « révolution culturelle » ? Aleksandra Kaurova « Localisme agressif » et « globalisme local » – La poétique des villes postsocialistes en Europe centrale Alfrun Kliems Politique mémorielle The Repositioning of Postsocialist Narratives of Nowa Huta and Dunaújváros Katarzyna Zechenter Kafka’s Statue: Memory and Forgetting in Postsocialist Prague Alfred Thomas Le Musée juif et le Centre pour la tolérance de Moscou Ewa Bérard Некрополи террора на территории Санкт-Петербурга и ленинградской области Alexander D. -

Television and the Cold War in the German Democratic Republic

0/-*/&4637&: *ODPMMBCPSBUJPOXJUI6OHMVFJU XFIBWFTFUVQBTVSWFZ POMZUFORVFTUJPOT UP MFBSONPSFBCPVUIPXPQFOBDDFTTFCPPLTBSFEJTDPWFSFEBOEVTFE 8FSFBMMZWBMVFZPVSQBSUJDJQBUJPOQMFBTFUBLFQBSU $-*$,)&3& "OFMFDUSPOJDWFSTJPOPGUIJTCPPLJTGSFFMZBWBJMBCMF UIBOLTUP UIFTVQQPSUPGMJCSBSJFTXPSLJOHXJUI,OPXMFEHF6OMBUDIFE ,6JTBDPMMBCPSBUJWFJOJUJBUJWFEFTJHOFEUPNBLFIJHIRVBMJUZ CPPLT0QFO"DDFTTGPSUIFQVCMJDHPPE Revised Pages Envisioning Socialism Revised Pages Revised Pages Envisioning Socialism Television and the Cold War in the German Democratic Republic Heather L. Gumbert The University of Michigan Press Ann Arbor Revised Pages Copyright © by Heather L. Gumbert 2014 All rights reserved This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (be- yond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publisher. Published in the United States of America by The University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America c Printed on acid- free paper 2017 2016 2015 2014 5 4 3 2 A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 978– 0- 472– 11919– 6 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978– 0- 472– 12002– 4 (e- book) Revised Pages For my parents Revised Pages Revised Pages Contents Acknowledgments ix Abbreviations xi Introduction 1 1 Cold War Signals: Television Technology in the GDR 14 2 Inventing Television Programming in the GDR 36 3 The Revolution Wasn’t Televised: Political Discipline Confronts Live Television in 1956 60 4 Mediating the Berlin Wall: Television in August 1961 81 5 Coercion and Consent in Television Broadcasting: The Consequences of August 1961 105 6 Reaching Consensus on Television 135 Conclusion 158 Notes 165 Bibliography 217 Index 231 Revised Pages Revised Pages Acknowledgments This work is the product of more years than I would like to admit. -

Der Rote Gott Stalin Und Die Deutschen Mit Freundlicher Unterstützung Des Fördervereins Gedenkstätte Berlin-Hohenschönhausen Der Rote Gott Stalin Und Die Deutschen

DER ROTE GOTT Stalin und die Deutschen Mit freundlicher Unterstützung des Fördervereins Gedenkstätte Berlin-Hohenschönhausen DER ROTE GOTT Stalin und die Deutschen Katalog zur Sonderausstellung Herausgegeben von Andreas Engwert und Hubertus Knabe für die Stiftung Gedenkstätte Berlin-Hohenschönhausen Stalin-Bilder vor 1945 Stalinismus in Deutschland 6 13 55 Vorwort Stalin und die Stalins Deutschland – Hubertus Knabe Kommunistische Partei die Durchsetzung der Deutschlands in der kommunistischen Diktatur Weimarer Republik in der Sowjetischen Bernhard H. Bayerlein Besatzungszone Stefan Donth 25 Das Bild Stalins 72 und der Sowjetunion im Opfer stalinistischer nationalsozialistischen Parteisäuberungen in Deutschland Hohenschönhausen Jan C. Behrends 75 34 Repression als Instrument Der Hitler-Stalin-Pakt stalinistischer Herrschaft in Ostdeutschland 37 Matthias Uhl Deutsche Genossen im Mahlstrom der „Großen 84 Säuberung“ 1936 bis 1938 Der Fall Robert Bialek Peter Erler 50 Die Stalinorgel Stalin-Kult in der DDR Entstalinisierung Anhang 89 161 174 Die Erfinder und Träger Stalins langer Schatten Autorenbiografien des Stalin-Kultes in der SBZ Hubertus Knabe und der frühen DDR Danksagung Jan C. Behrends 170 Ein fataler Druckfehler – Leih- und Lizenzgeber 98 der Fall Tribüne Musterstücke des 175 Sozialismus – Geschenke Literaturempfehlung zu Stalins 70. Geburtstag 176 100 Bildnachweis Die Stalin-Note Impressum 103 Deutschlands bester Freund – Stalin und die deutschen Intellektuellen Gerd Koenen 109 Ein neuer Städtebau zur Legitimation der DDR: Der zentrale Platz in Berlin Jörn Düwel 126 Die Stalin-Pavillons – Kapellen der Deutsch- Sowjetischen Freundschaft 129 Ikonografie des Stalin-Kultes in der DDR Andreas Engwert Hubertus Knabe Vorwort Josef Wissarionowitsch Dschugaschwili – kaum ein anderer ausländischer Politiker des 20. Jahrhunderts hat so nachhaltigen Einfluss auf Deutschland ausgeübt wie der georgische Politiker, der unter dem Kampfnamen Stalin (der Stählerne) fast 30 Jahre an der Spitze der Sowjetunion stand. -

Erinnern! Aufgabe, Chance, Herausforderung

Erinnern! Aufgabe, Chance, Herausforderung. 2 | 2 017 1933 1945 1989 Zehn Jahre Stiftung Gedenkstätten Sachsen-Anhalt Bilanz und Ausblick Kai Langer 1 Martin Luther in der DDR. Vom „Fürstenknecht“ zu einem „der größten Söhne des deutschen Volkes“ Jan Scheunemann 33 Rudolf Bahros „Die Alternative“ – Dokument einer Politischen Theologie? Thomas Schubert 45 Perspektivwechsel – Wechselperspektive. Die Ausstellung „Wechselseitig. Rück- und Zuwanderung in die DDR 1949 bis 1989“ Eva Fuchslocher, Michael Schäbitz 59 Luthers Erben im Visier des Geheimdienstes oder: Pfarrer Hamel gefährdet den Weltfrieden André Gursky 75 Fonds „Heimerziehung in der DDR in den Jahren 1949 bis 1990“ Gundel Berger 88 Die Gedenkstätte für die Erschießung von polnischen Zwangsarbeitern im Schacht Schermen Annett Hehmann, Klaus Möbius, Reinhard Ritter, Axel Thiem 92 Über ein Schülerprojekt, das in Genthin für die Wanderausstellung „Justiz im Nationalsozialismus. Über Verbrechen im Namen des Deutschen Volkes. Sachsen- Anhalt“ im Rahmen des Freiwilligen Sozialen Jahres (FSJ) entwickelt wurde Jerome Kageler 102 Menschenrechte fallen nicht vom Himmel – Charta 77 und das Querfurter Papier Lothar Tautz 106 Inhalt Aus der Arbeit der Stiftung „Ich wollte sie alle mit Namen nennen“ Die Anfänge des sowjetischen GULag im Weißen Meer – Studienreise der Bundes- stiftung zur Aufarbeitung der SED-Diktatur im August 2017 nach Russland Edda Ahrberg, Kai Langer 116 „Reise der Erinnerung“ – Ein Tagebuch Femke Opper 127 Zur Lehramtsausbildung: Das Außerunterrichtliche Pädagogische Praktikum (AuPP) für Lehramtsstudierende in der Stiftung Gedenkstätten Sachsen-Anhalt Stefan Henze 136 Aus der Arbeit der Stiftung André Gursky 141 20 Jahre Internationales Workcamp am Grenzdenkmal Hötensleben Susan Baumgartl, René Müller 144 Gedenkstunde am 26. Mai 2017 am Grenzdenkmal Hötensleben zum 65. -

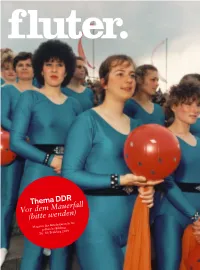

Thema DDR Vor Dem Mauerfall (Bitte Wenden)

Thema DDR Vor dem Mauerfall (bitte wenden) Magazin der Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung Nr. 30 / Frühling 2009 Was nicht in Alle bpb-Produkte unter www.bpb.de EDITORIAL INHALT diesem Heft steht, steht woanders Die DDR war einmal. »Sich dumm zu stellen, war eine Form von Und zwar hier: Sachbücher, Für viele ist es ein Land, das sie nur aus Erzählungen Opposition« . Seite 4 kennen. Aus diesem Block historischen Materials, Zuckerbrot und Peitsche: Der Historiker Stefan Romane, Broschüren, Filme der durch die Entfernung oft etwas Märchenhaf- Wolle über den Alltag in der DDR und den sprung- & Links zum Thema tes bekommt, hat fluter einige Geschichten heraus- haften Umgang der Regierung mit dem Volk gegriffen. Bei aller Komplexität – es gibt ein paar einfache Wahrheiten: Ein Staat, der seine Bürger Ein Stück Karibik . Seite 10 einsperrt und ermordet, wenn sie fliehen wollen, Es wäre ja auch zu schön gewesen: Die Geschichte ist kein guter Staat. Ein politisches System, das ei- von einer DDR-Insel brachte Wind in die Köpfe ner kleinen Gruppe alter Männer unkontrollierte Macht über alles gibt, ist eine Diktatur. Auch wenn Lost in Music . Seite 11 Stefan Wolle: Werner Bräunig: ONLINE: Die heile Welt der Diktatur Rummelplatz sie sich den Namen »Demokratische Republik« Völlig aus dem Takt: Nichts haben die Machthaber Stefan Wolle gelingt es, die widersprüchlichen Bilder Nach dem Vorabdruck einiger Kapitel fiel Bräunig, Auf der Seite »Deine Geschichte«können Jugend- gibt. Diktaturen sind im besten Fall absurd und in so gefürchtet wie Jugendbewegungen. Rock, Beat einer unter gegangenen Welt zusammenzufügen. der schreibende Bergmann, bei der SED in Ungnade.