The Mercator Projection: Its Uses, Misuses, and Its Association with Scientific Information and the Rise of Scientific Societies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Geographic Board Games

GSR_3 Geospatial Science Research 3. School of Mathematical and Geospatial Science, RMIT University December 2014 Geographic Board Games Brian Quinn and William Cartwright School of Mathematical and Geospatial Sciences RMIT University, Australia Email: [email protected] Abstract Geographic Board Games feature maps. As board games developed during the Early Modern Period, 1450 to 1750/1850, the maps that were utilised reflected the contemporary knowledge of the Earth and the cartography and surveying technologies at their time of manufacture and sale. As ephemera of family life, many board games have not survived, but those that do reveal an entertaining way of learning about the geography, exploration and politics of the world. This paper provides an introduction to four Early Modern Period geographical board games and analyses how changes through time reflect the ebb and flow of national and imperial ambitions. The portrayal of Australia in three of the games is examined. Keywords: maps, board games, Early Modern Period, Australia Introduction In this selection of geographic board games, maps are paramount. The games themselves tend to feature a throw of the dice and moves on a set path. Obstacles and hazards often affect how quickly a player gets to the finish and in a competitive situation whether one wins, or not. The board games examined in this paper were made and played in the Early Modern Period which according to Stearns (2012) dates from 1450 to 1750/18501. In this period printing gradually improved and books and journals became more available, at least to the well-off. Science developed using experimental techniques and real world observation; relying less on classical authority. -

Factors Affecting Ground-Water Exchange and Catchment Size for Florida Lakes in Mantled Karst Terrain

Factors Affecting Ground-Water Exchange and Catchment Size for Florida Lakes in Mantled Karst Terrain Water-Resources Investigations Report 02-4033 GROUND-WATER WATER TABLE CATCHMENT Undifferentiated Lake Surficial Deposits Lake Sediment Breaches in Intermediate Intermediate Confining Unit Confining Unit U.S. Geological Survey Prepared in cooperation with the Southwest Florida Water Management District and the St. Johns River Water Management District Factors Affecting Ground-Water Exchange and Catchment Size for Florida Lakes in Mantled Karst Terrain By T.M. Lee U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Water-Resources Investigations Report 02-4033 Prepared in cooperation with the SOUTHWEST FLORIDA WATER MANAGEMENT DISTRICT and the ST. JOHNS RIVER WATER MANAGEMENT DISTRICT Tallahassee, Florida 2002 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR GALE A. NORTON, Secretary U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY CHARLES G. GROAT, Director The use of firm, trade, and brand names in this report is for identification purposes only and does not constitute endorsement by the U.S. Geological Survey. For additional information Copies of this report can be write to: purchased from: District Chief U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Geological Survey Branch of Information Services Suite 3015 Box 25286 227 N. Bronough Street Denver, CO 80225-0286 Tallahassee, FL 32301 888-ASK-USGS Additional information about water resources in Florida is available on the World Wide Web at http://fl.water.usgs.gov CONTENTS Abstract................................................................................................................................................................................. -

Water Flow in the Silurian-Devonian Aquifer System, Johnson County, Iowa

Hydrogeology and Simulation of Ground- Water Flow in the Silurian-Devonian Aquifer System, Johnson County, Iowa By Patrick Tucci (U.S. Geological Survey) and Robert M. McKay (Iowa Department of Natural Resources, Iowa Geological Survey) Prepared in cooperation with The Iowa Department of Natural Resources – Water Supply Bureau City of Iowa City Johnson County Board of Supervisors City of Coralville The University of Iowa City of North Liberty City of Solon Scientific Investigations Report 2005–5266 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior Gale A. Norton, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey P. Patrick Leahy, Acting Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2006 For product and ordering information: World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS For more information on the USGS--the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment: World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this report is in the public domain, permission must be secured from the individual copyright owners to reproduce any copyrighted materials contained within this report. Suggested citation: Tucci, Patrick and McKay, Robert, 2006, Hydrogeology and simulation of ground-water flow in the Silurian-Devonian aquifer system, Johnson County, Iowa: U.S. Geological Survey, Scientific Investigations -

Erwin Raisz' Atlases

Erwin Raisz‘ Atlases – an early multi-method approach to cartographic communication (Eric Losang) ICC-Preconference-Workshop: Atlases and Infographics Tokyo, 2019/ 07/ 13 Outline • Erwin Raisz – biography and opus • The concept behind Raisz‘ work • Three Atlases • Atlas of Global Geography • Atlas of Cuba • Atlas of Florida • Possible Importance of the three Atlases • Communication • Storytelling Biography • * 1 March 1893, Lőcse, Hungary • 1914 degree in civil engineering and architecture Royal Polytechnicum in Budapest • 1923 Immigration US • 1924/1929 Master/Ph.D. Geology, Columbia University • 1931 Institute of Geographical Exploration at Harvard University (proposed by W. M. Davies, teaching Cartography) • 1938 General Cartography (first cartographic textbook in English) • 1951 Clark University, Boston; from 1957 University of Florida • + 1968, Bangkok while travelling to the IGU in Dehli. Landform (physiographic) Maps • Influenced by W.M. Davies, I. Bowman and N. Fenneman (physiographic provinces) • Goal: explaining territory within its physiographic instead of (man made) county borders Landform (physiographic) Maps Landform (physiographic) Maps • Influenced by W.M. Davies, I. Bowman and N. Fenneman (physiographic provinces) • Goal: explaining territory within its physiographic instead of (man made) county borders • Geodeterministic answer to a prevailling statistical approach to geography (H. Gannett) Landform (physiographic) Maps • Influenced by W.M. Davies, I. Bowman and N. Fenneman (physiographic provinces) • Goal: explaining territory within its physiographic instead of (man made) county borders • Geodeterministic answer to a prevailling statistical approach to geography (H. Gannett) • Method: Delineate the significant elements of the terrain in pictorial-diagrammatic fashion Statistical atlas of the United States 1898 Landform (physiographic) Maps • Influenced by W.M. Davies, I. Bowman and N. -

The History of Cartography, Volume 3

THE HISTORY OF CARTOGRAPHY VOLUME THREE Volume Three Editorial Advisors Denis E. Cosgrove Richard Helgerson Catherine Delano-Smith Christian Jacob Felipe Fernández-Armesto Richard L. Kagan Paula Findlen Martin Kemp Patrick Gautier Dalché Chandra Mukerji Anthony Grafton Günter Schilder Stephen Greenblatt Sarah Tyacke Glyndwr Williams The History of Cartography J. B. Harley and David Woodward, Founding Editors 1 Cartography in Prehistoric, Ancient, and Medieval Europe and the Mediterranean 2.1 Cartography in the Traditional Islamic and South Asian Societies 2.2 Cartography in the Traditional East and Southeast Asian Societies 2.3 Cartography in the Traditional African, American, Arctic, Australian, and Pacific Societies 3 Cartography in the European Renaissance 4 Cartography in the European Enlightenment 5 Cartography in the Nineteenth Century 6 Cartography in the Twentieth Century THE HISTORY OF CARTOGRAPHY VOLUME THREE Cartography in the European Renaissance PART 1 Edited by DAVID WOODWARD THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS • CHICAGO & LONDON David Woodward was the Arthur H. Robinson Professor Emeritus of Geography at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London © 2007 by the University of Chicago All rights reserved. Published 2007 Printed in the United States of America 1615141312111009080712345 Set ISBN-10: 0-226-90732-5 (cloth) ISBN-13: 978-0-226-90732-1 (cloth) Part 1 ISBN-10: 0-226-90733-3 (cloth) ISBN-13: 978-0-226-90733-8 (cloth) Part 2 ISBN-10: 0-226-90734-1 (cloth) ISBN-13: 978-0-226-90734-5 (cloth) Editorial work on The History of Cartography is supported in part by grants from the Division of Preservation and Access of the National Endowment for the Humanities and the Geography and Regional Science Program and Science and Society Program of the National Science Foundation, independent federal agencies. -

Geocart 3 User's Manual

User’s Manual Credits Application design & programming ........ Daniel “daan” Strebe & Paul J. Messmer. Manual design & authorship ................... Daniel “daan” Strebe, with Paul J. Messmer (Chapter 1, Appendices G&H.) Thanks to Tiffany M. Lillie, Sirus A Strebe, & Matthew Strebe for proofreading and many helpful comments. Dedicated to the memory of John Parr Snyder extraordinary researcher of and historian of map projections. He encouraged me. — daan Manual composed and edited using: • Adobe InDesign™ CS4 • Geocart™ • Adobe Photoshop™ • Adobe Illustrator™ This manual is typeset primarily in Adobe Garamond Pro with headings in Myriad Pro. Notices This manual describes Geocart 3.1. The maps you make with Geocart may be used however you see fit without license and without having to credit Geocart (though we would appreciate if you would when it is reasonable to do so). However, if you use geographic databases not supplied with Geocart, then you are responsible for properly licensing them. Some map projections included in Geocart were patented. Mapthematics LLC believes patents on all included projections have expired but accepts no responsibility for alleged infringement. Some corporations use logos similar in form to some map projections available in Geocart. The user of the Geocart software accepts sole responsibility for their use. The name Geocart is trademarked by Daniel R. Strebe in the United States of America. The Geocart software is copyrighted material belonging to Mapthematics LLC and Special Case Software LLC. You may not make copies of Geocart for other than backup purposes, and you may not lend or sell Geocart to another person or corporation unless you destroy all of your own copies before doing so. -

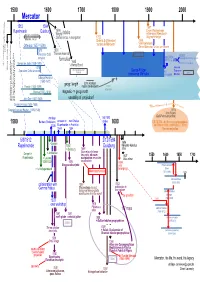

Visio-MERCATOR ENG2.Vsd

1500 1600 1700 1800 1900 2000 Mercator 1512 1594 1897 Rupelmonde Duisburg 1599 tables Lt-gen Wauwermans Italian composite Wright tables article about Mercator in Certain erros in navigation 1752 Biographie belge atlases IATO 1869 middle 15th Century Diderot & d’Alembert “cartes de Mercator” Van Raemdonck Ortelius (1527-1598) Gérard Mercator, sa vie, son oeuvre printing 1570 1600 Theatrum Orbis Thomas Harrriot projection MGRS terrarum 1772 1825 1914 post WWI military grid reference system formulas Johan Lambert Carl Friedrich Gauss Johann Krüger NATO UTM Gerard de Jode (1509-1591) 1645 transverse Mercator transverse Mercator transverse Mercator civil reference system fall of Constantinople Henry Bond 1578 (sphere) (ellipsoid) (ellipsoid) Universal 1492 end of Reconquista Mercatorprojection Transverse Speculum Orbis terrarum formula Gauss-Krüger 1942 grid transverse Mercator developped Mercator Judocus Hondius (1563-1612) + geogr. length John Harrison Plantijn (1520-1589) marine timekeepers use of projection Moretus (1543-1610) magnetic <> geogr north John Dee (1527-1608) useability of projection? 1488 Bartholomeus Dias rounded Cape of Good Hope 1492 Columbus ‘America’ discovered 1498 Vasco da Gama reached India via Africa 1519 – 1522 Magellan around the world Gemma Frisius (1508-1555) 1904 criticism + -- Gaspard van der Heyden (1496-1549) 1974 Arne Peters (Gall-Peters-projection) mariage 5/5/1590 1500 Barbara Shellekens arrested in met Ortelius stroke 1600 CRITICISM - but from non-cartographers - 1536 Rupelmonde in Frankfurt on ethnocentrism, -

FOR PEOPLE WHO LOVE EARLY MAPS 99298 IMCOS Covers 2012 Layout 1 06/02/2012 09:45 Page 5

IMCSJOURNAL S pr ing 2013 | Number 132 FOR PEOPLE WHO LOVE EARLY MAPS 99298 IMCOS covers 2012_Layout 1 06/02/2012 09:45 Page 5 THE MAP HOUSE OF LONDON (established 1907) Antiquarian Maps, Atlases, Prints & Globes 54 BEAUCHAMP PLACE KNIGHTSBRIDGE LONDON SW3 1NY Telephone: 020 7589 4325 or 020 7584 8559 Fax: 020 7589 1041 Email: [email protected] www.themaphouse.com JOURNAL OF THE INTERNATIONAL MAP COLLECTORS’ SOCIETY FOUNDED S pr ing 2013 | Number 132 1980 FEATURES Mercator and his ‘Atlas of Europe’ 13 Self-protection, official obligations and the pursuit of truth Peter Barber High in the Andes partii 25 Further adventures of the French Academy expedition to Peru Richard Smith ‘The Dutch colony of The Cape of Good Hope’ 30 A map by L.S. De la Rochette Roger Stewart REGULAR ITEMS A Letter from the Chairman 3 Hans Kok From the Editor’s Desk 5 Ljiljana Ortolja-Baird IMCoS Matters 7 Mapping Matters 37 Worth a Look 46 You Write to Us 49 Book Reviews 53 Copy and other material for our next issue (Summer 2013) should be submitted by 1 April 2013. Editorial items should be sent to the Editor Ljiljana Ortolja-Baird, email [email protected] or 14 Hallfield, Quendon, Essex CB11 3XY United Kingdom Consultant Editor Valerie Newby Designer Catherine French Advertising Jenny Harvey, 27 Landford Road, Putney, London SW15 1AQ United Kingdom Tel +44 (0)20 8789 7358, email [email protected] Please note that acceptance of an article for publication gives IMCoS the right to place it on our website. -

Early & Rare World Maps, Atlases & Rare Books

19219a_cover.qxp:Layout 1 5/10/11 12:48 AM Page 1 EARLY & RARE WORLD MAPS, ATLASES & RARE BOOKS Mainly from a Private Collection MARTAYAN LAN CATALOGUE 70 EAST 55TH STREET • NEW YORK, NEW YORK 10022 45 To Order or Inquire: Telephone: 800-423-3741 or 212-308-0018 Fax: 212-308-0074 E-Mail: [email protected] Website: www.martayanlan.com Gallery Hours: Monday through Friday 9:30 to 5:30 Saturday and Evening Hours by Appointment. We welcome any questions you might have regarding items in the catalogue. Please let us know of specific items you are seeking. We are also happy to discuss with you any aspect of map collecting. Robert Augustyn Richard Lan Seyla Martayan James Roy Terms of Sale: All items are sent subject to approval and can be returned for any reason within a week of receipt. All items are original engrav- ings, woodcuts or manuscripts and guaranteed as described. New York State residents add 8.875 % sales tax. Personal checks, Visa, MasterCard, American Express, and wire transfers are accepted. To receive periodic updates of recent acquisitions, please contact us or register on our website. Catalogue 45 Important World Maps, Atlases & Geographic Books Mainly from a Private Collection the heron tower 70 east 55th street new york, new york 10022 Contents Item 1. Isidore of Seville, 1472 p. 4 Item 2. C. Ptolemy, 1478 p. 7 Item 3. Pomponius Mela, 1482 p. 9 Item 4. Mer des hystoires, 1491 p. 11 Item 5. H. Schedel, 1493, Nuremberg Chronicle p. 14 Item 6. Bergomensis, 1502, Supplementum Chronicum p. -

Recent Publications 1984 — 2017 Issues 1 — 100

RECENT PUBLICATIONS 1984 — 2017 ISSUES 1 — 100 Recent Publications is a compendium of books and articles on cartography and cartographic subjects that is included in almost every issue of The Portolan. It was compiled by the dedi- cated work of Eric Wolf from 1984-2007 and Joel Kovarsky from 2007-2017. The worldwide cartographic community thanks them greatly. Recent Publications is a resource for anyone interested in the subject matter. Given the dates of original publication, some of the materi- als cited may or may not be currently available. The information provided in this document starts with Portolan issue number 100 and pro- gresses to issue number 1 (in backwards order of publication, i.e. most recent first). To search for a name or a topic or a specific issue, type Ctrl-F for a Windows based device (Command-F for an Apple based device) which will open a small window. Then type in your search query. For a specific issue, type in the symbol # before the number, and for issues 1— 9, insert a zero before the digit. For a specific year, instead of typing in that year, type in a Portolan issue in that year (a more efficient approach). The next page provides a listing of the Portolan issues and their dates of publication. PORTOLAN ISSUE NUMBERS AND PUBLICATIONS DATES Issue # Publication Date Issue # Publication Date 100 Winter 2017 050 Spring 2001 099 Fall 2017 049 Winter 2000-2001 098 Spring 2017 048 Fall 2000 097 Winter 2016 047 Srping 2000 096 Fall 2016 046 Winter 1999-2000 095 Spring 2016 045 Fall 1999 094 Winter 2015 044 Spring -

Knowing and Decorating the World Illustrations and Textual Descriptions in the Maps of the Fourth Edition of the Mercator-Hondius Atlas (1613)

OTTO LATVA AND JOHANNA SKURNIK Knowing and decorating the world Illustrations and textual descriptions in the maps of the fourth edition of the Mercator-Hondius Atlas (1613) his article analyses the Mercator-Hondius Atlas depicted on the maps authored by Mercator and maps in the context of constructing knowl- Hondius. We investigate the illustrations and textual Tedge of the world. In what follows, we analyse descriptions Mercator and Hondius used to represent the elem ents of continental geographies and ocean the world and its regions. These two men each applied spaces on the maps presented in the atlas. We take as very different principles when preparing maps: our starting point the tension between empirical and Mercator considered himself to be a scholar aiming theoretical knowledge and examine the changes occur- to produce the most accurate maps and emphasizing ring in the ways of representing land and sea on atlas their informative content. Hondius, however, evolved maps which are evident in the Mercator-Hondius Atlas. from an engraver to a publisher of atlases and globes, Consequently, we investigate how the world was rep- turning them into a profitable business (van der resented through information in pictorial and textual Krogt 1997: 35; Zuber 2011: 516). We argue that the form. We argue that the maps in the Mercator-Hondius maps in the Mercator-Hondius Atlas can be read as a Atlas make explicit not only the multiple cartographical demonstration of the layered nature of the atlas as an trad itions and the layered nature of atlases as artefacts. epistemological artefact. They also exemplify the various coexisting functions of The principles and practices employed by dif- the atlas. -

Bibliography of Map Projections

AVAILABILITY OF BOOKS AND MAPS OF THE U.S. GEOlOGICAL SURVEY Instructions on ordering publications of the U.S. Geological Survey, along with prices of the last offerings, are given in the cur rent-year issues of the monthly catalog "New Publications of the U.S. Geological Survey." Prices of available U.S. Geological Sur vey publications released prior to the current year are listed in the most recent annual "Price and Availability List" Publications that are listed in various U.S. Geological Survey catalogs (see back inside cover) but not listed in the most recent annual "Price and Availability List" are no longer available. Prices of reports released to the open files are given in the listing "U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Reports," updated month ly, which is for sale in microfiche from the U.S. Geological Survey, Books and Open-File Reports Section, Federal Center, Box 25425, Denver, CO 80225. Reports released through the NTIS may be obtained by writing to the National Technical Information Service, U.S. Department of Commerce, Springfield, VA 22161; please include NTIS report number with inquiry. Order U.S. Geological Survey publications by mail or over the counter from the offices given below. BY MAIL OVER THE COUNTER Books Books Professional Papers, Bulletins, Water-Supply Papers, Techniques of Water-Resources Investigations, Circulars, publications of general in Books of the U.S. Geological Survey are available over the terest (such as leaflets, pamphlets, booklets), single copies of Earthquakes counter at the following Geological Survey Public Inquiries Offices, all & Volcanoes, Preliminary Determination of Epicenters, and some mis of which are authorized agents of the Superintendent of Documents: cellaneous reports, including some of the foregoing series that have gone out of print at the Superintendent of Documents, are obtainable by mail from • WASHINGTON, D.C.--Main Interior Bldg., 2600 corridor, 18th and C Sts., NW.