From the Old Ages to Mercator

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Analyze a World Map

Analyze a World Map Materials: Map of the World: Political or use link this website Map of the World Worksheet You could start the discussion by saying that the social studies part of the GED test assumes that everyone has a basic knowledge of world geography. The test will contain maps that you have to analyze and the answers are not always directly on the map. This is one area of the test where they expect you to just know the approximate locations of countries and oceans. So we thought we would use this world map to familiarize everyone with some world geography. Hand out the maps. The first thing you need to do with a map is read the title so that you know what you are looking at. Ask, “What is the title of this map?” ‘Map of the World: Political”. So this map should give us information about the location of countries. Then look to see if there is a legend or a list of symbols that explains the information shown on the map. Ask, “Is there a legend for this map/” Yes, it shows the scale of the map. You can discuss that the scale shows the relationship between distances on the map to the actual distance on the ground. Look to see if there is anything on the map showing directions, most maps have a compass that shows east, west, north, and south. Ask, “Does this map have any symbols indicating direction?” Yes, this map has a direction compass that shows points north. Ask if students know where south, east, and west are on the map. -

Countries and Continents of the World: a Visual Model

Countries and Continents of the World http://geology.com/world/world-map-clickable.gif By STF Members at The Crossroads School Africa Second largest continent on earth (30,065,000 Sq. Km) Most countries of any other continent Home to The Sahara, the largest desert in the world and The Nile, the longest river in the world The Sahara: covers 4,619,260 km2 The Nile: 6695 kilometers long There are over 1000 languages spoken in Africa http://www.ecdc-cari.org/countries/Africa_Map.gif North America Third largest continent on earth (24,256,000 Sq. Km) Composed of 23 countries Most North Americans speak French, Spanish, and English Only continent that has every kind of climate http://www.freeusandworldmaps.com/html/WorldRegions/WorldRegions.html Asia Largest continent in size and population (44,579,000 Sq. Km) Contains 47 countries Contains the world’s largest country, Russia, and the most populous country, China The Great Wall of China is the only man made structure that can be seen from space Home to Mt. Everest (on the border of Tibet and Nepal), the highest point on earth Mt. Everest is 29,028 ft. (8,848 m) tall http://craigwsmall.wordpress.com/2008/11/10/asia/ Europe Second smallest continent in the world (9,938,000 Sq. Km) Home to the smallest country (Vatican City State) There are no deserts in Europe Contains mineral resources: coal, petroleum, natural gas, copper, lead, and tin http://www.knowledgerush.com/wiki_image/b/bf/Europe-large.png Oceania/Australia Smallest continent on earth (7,687,000 Sq. -

Geography Notes.Pdf

THE GLOBE What is a globe? a small model of the Earth Parts of a globe: equator - the line on the globe halfway between the North Pole and the South Pole poles - the northern-most and southern-most points on the Earth 1. North Pole 2. South Pole hemispheres - half of the earth, divided by the equator (North & South) and the prime meridian (East and West) 1. Northern Hemisphere 2. Southern Hemisphere 3. Eastern Hemisphere 4. Western Hemisphere continents - the largest land areas on Earth 1. North America 2. South America 3. Europe 4. Asia 5. Africa 6. Australia 7. Antarctica oceans - the largest water areas on Earth 1. Atlantic Ocean 2. Pacific Ocean 3. Indian Ocean 4. Arctic Ocean 5. Antarctic Ocean WORLD MAP ** NOTE: Our textbooks call the “Southern Ocean” the “Antarctic Ocean” ** North America The three major countries of North America are: 1. Canada 2. United States 3. Mexico Where Do We Live? We live in the Western & Northern Hemispheres. We live on the continent of North America. The other 2 large countries on this continent are Canada and Mexico. The name of our country is the United States. There are 50 states in it, but when it first became a country, there were only 13 states. The name of our state is New York. Its capital city is Albany. GEOGRAPHY STUDY GUIDE You will need to know: VOCABULARY: equator globe hemisphere continent ocean compass WORLD MAP - be able to label 7 continents and 5 oceans 3 Large Countries of North America 1. United States 2. Canada 3. -

Was This World Map Made Ten Centuries Ago?

HAWAIIAN GAZETTE, FRIDAY, JANUARY n, 1907 SEMI-WEEKL- Y Was This World Map Made Ten Centuries Ago? gg "J" ISOME DETAILS OF GREAT Vf? rr9rv-vr- i 'vir)('JK.rr KXW XXXjtXXmXmKiXXXiXXX XvyXXXrXXX ffKftXr1 STORM Politically Inclined policemen nro not wanted by tho new Sheriff, who will MAUI, shortly Issue nn order to the effect that January i. The holiday sea- son 2 i I nlj employes of tho police department on Maul has not been a tlmo of quiet 5 j ft must chooso between their Jobs on tho enjoyment ns far as weather is 5 a force and their oITlces In any of tho concerned. Dame Nnturo has echoed A.- -. a. w three political party committees. This anything but the Christmas sentiment rule Is to bo strictly enforced, the em of "peace on earth and good-wi- lt ployes of tho public being supposed, bo mn." far as tho police are concernod at least, Before recovery could bo made from to give their time and energy to th tho effects of the recent north storm public and not for the advancement with Its 20 Inches of moisture In local- politically or otherwlso of any one sec- ities, on Saturday tho wind changed Ifr tion of tho public to the southucst and nn kona Tho Sheriff Is making plain storm came Into being. It contin- If It that ued to blow fiercely ho means ho says all tho night what when he tabued through, accompanied by nn Incessant i - i politics around tho police station. In piny of lightning and the heavy roll of this he has come In for moro or less thunder. -

General Index

General Index Italic page numbers refer to illustrations. Authors are listed in ical Index. Manuscripts, maps, and charts are usually listed by this index only when their ideas or works are discussed; full title and author; occasionally they are listed under the city and listings of works as cited in this volume are in the Bibliograph- institution in which they are held. CAbbas I, Shah, 47, 63, 65, 67, 409 on South Asian world maps, 393 and Kacba, 191 "Jahangir Embracing Shah (Abbas" Abywn (Abiyun) al-Batriq (Apion the in Kitab-i balJriye, 232-33, 278-79 (painting), 408, 410, 515 Patriarch), 26 in Kitab ~urat ai-arc!, 169 cAbd ai-Karim al-Mi~ri, 54, 65 Accuracy in Nuzhat al-mushtaq, 169 cAbd al-Rabman Efendi, 68 of Arabic measurements of length of on Piri Re)is's world map, 270, 271 cAbd al-Rabman ibn Burhan al-Maw~ili, 54 degree, 181 in Ptolemy's Geography, 169 cAbdolazlz ibn CAbdolgani el-Erzincani, 225 of Bharat Kala Bhavan globe, 397 al-Qazwlni's world maps, 144 Abdur Rahim, map by, 411, 412, 413 of al-BlrunI's calculation of Ghazna's on South Asian world maps, 393, 394, 400 Abraham ben Meir ibn Ezra, 60 longitude, 188 in view of world landmass as bird, 90-91 Abu, Mount, Rajasthan of al-BlrunI's celestial mapping, 37 in Walters Deniz atlast, pl.23 on Jain triptych, 460 of globes in paintings, 409 n.36 Agapius (Mabbub) religious map of, 482-83 of al-Idrisi's sectional maps, 163 Kitab al- ~nwan, 17 Abo al-cAbbas Abmad ibn Abi cAbdallah of Islamic celestial globes, 46-47 Agnese, Battista, 279, 280, 282, 282-83 Mu\:lammad of Kitab-i ba/Jriye, 231, 233 Agnicayana, 308-9, 309 Kitab al-durar wa-al-yawaqft fi 11m of map of north-central India, 421, 422 Agra, 378 n.145, 403, 436, 448, 476-77 al-ra~d wa-al-mawaqft (Book of of maps in Gentil's atlas of Mughal Agrawala, V. -

The Baader Planetarium

1 THE BAADER PLANETARIUM INSTRUCTION MANUAL BAADER PLANETARIUM Zur Sternwarte M 82291 Mammendorf M Tel. 08145/8802 M Fax 08145/8805 www.baader-planetarium.de M [email protected] M www.celestron-deutschland.de 2 HINTS/TECHNICAL 1. YOUR PLANETARIUM OPERATES BY A DC MINIATUR MOTOR. IT'S LIFETIME IS THEREFORE LIMITED. PLEASE HAVE THE MOTOR USUALLY RUN IN THE SLOWEST SPEED POSSIBLE. FOR EXHIBITIONS OR PERMANENT DISPLAY A TIME LIMIT SWITCH IS A MUST. 2. DON'T HAVE THE SUNBULB WORKING IN THE HIGHEST STEP CONTINUOUSLY. THIS STEP IS FORSEEN ONLY FOR PROJECTING THE HEAVENS IF THE PLASTIC SUNCAP IS REMOVED. 3. CLOSE THE SPHERE AT ANY TIME POSSIBLE. HINTS/THEORETICAL 1. ESPECIALLY GIVE ATTENTION TO PAGE 5-3.F OF THE MANUAL. 2. CLOSE THE SPHERE SO THAT THE ORBIT LINES OF THE PLANETS INSIDE FIT CORRECTLY PAGE 6-5.A. 3. USUALLY DEMONSTRATE BY KEEPING THE EARTH'S ORBIT HORIZONTAL. 4. A SPECIAL EXPLANTATION FOR THE SEASONS IS POSSIBLE IF YOU TURN THE SPHERE TO A HORIZONTAL CELESTIAL EQUATOR. NOW THE EARTH MOVES UP AND DOWN ON ITS WAY AROUND THE SUN. MENTION THE APPEARING LIGHTPHASES. 5. REMEMBER THE GREATEST FINDING OF COPERNICUS: THE DISTANCE EARTH - SUN IS NEARLY ZERO COMPARED TO THE DISTANCE OF THE FIXED STARS. IN REALITY THE WHOLE SOLAR SYSTEM IN THE CELESTIAL SPHERE WOULD BE A PINPOINT IN THE CENTER. THIS HELPS TO UNDERSTAND THE MINUTE STELLAR PARALLAXE AND THE "FIXED" POSITION OF THE STARS COMPARED TO THE SUN'S CHANGING HEIGHT OVER THE HORIZON DURING THE YEAR. 3 INTRODUCTION For countless centuries the stars have been objects of mystery. -

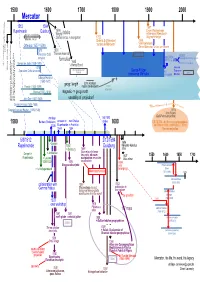

Visio-MERCATOR ENG2.Vsd

1500 1600 1700 1800 1900 2000 Mercator 1512 1594 1897 Rupelmonde Duisburg 1599 tables Lt-gen Wauwermans Italian composite Wright tables article about Mercator in Certain erros in navigation 1752 Biographie belge atlases IATO 1869 middle 15th Century Diderot & d’Alembert “cartes de Mercator” Van Raemdonck Ortelius (1527-1598) Gérard Mercator, sa vie, son oeuvre printing 1570 1600 Theatrum Orbis Thomas Harrriot projection MGRS terrarum 1772 1825 1914 post WWI military grid reference system formulas Johan Lambert Carl Friedrich Gauss Johann Krüger NATO UTM Gerard de Jode (1509-1591) 1645 transverse Mercator transverse Mercator transverse Mercator civil reference system fall of Constantinople Henry Bond 1578 (sphere) (ellipsoid) (ellipsoid) Universal 1492 end of Reconquista Mercatorprojection Transverse Speculum Orbis terrarum formula Gauss-Krüger 1942 grid transverse Mercator developped Mercator Judocus Hondius (1563-1612) + geogr. length John Harrison Plantijn (1520-1589) marine timekeepers use of projection Moretus (1543-1610) magnetic <> geogr north John Dee (1527-1608) useability of projection? 1488 Bartholomeus Dias rounded Cape of Good Hope 1492 Columbus ‘America’ discovered 1498 Vasco da Gama reached India via Africa 1519 – 1522 Magellan around the world Gemma Frisius (1508-1555) 1904 criticism + -- Gaspard van der Heyden (1496-1549) 1974 Arne Peters (Gall-Peters-projection) mariage 5/5/1590 1500 Barbara Shellekens arrested in met Ortelius stroke 1600 CRITICISM - but from non-cartographers - 1536 Rupelmonde in Frankfurt on ethnocentrism, -

The Magic of the Atwood Sphere

The magic of the Atwood Sphere Exactly a century ago, on June Dr. Jean-Michel Faidit 5, 1913, a “celestial sphere demon- Astronomical Society of France stration” by Professor Wallace W. Montpellier, France Atwood thrilled the populace of [email protected] Chicago. This machine, built to ac- commodate a dozen spectators, took up a concept popular in the eigh- teenth century: that of turning stel- lariums. The impact was consider- able. It sparked the genesis of modern planetariums, leading 10 years lat- er to an invention by Bauersfeld, engineer of the Zeiss Company, the Deutsche Museum in Munich. Since ancient times, mankind has sought to represent the sky and the stars. Two trends emerged. First, stars and constellations were easy, especially drawn on maps or globes. This was the case, for example, in Egypt with the Zodiac of Dendera or in the Greco-Ro- man world with the statue of Atlas support- ing the sky, like that of the Farnese Atlas at the National Archaeological Museum of Na- ples. But things were more complicated when it came to include the sun, moon, planets, and their apparent motions. Ingenious mecha- nisms were developed early as the Antiky- thera mechanism, found at the bottom of the Aegean Sea in 1900 and currently an exhibi- tion until July at the Conservatoire National des Arts et Métiers in Paris. During two millennia, the human mind and ingenuity worked constantly develop- ing and combining these two approaches us- ing a variety of media: astrolabes, quadrants, armillary spheres, astronomical clocks, co- pernican orreries and celestial globes, cul- minating with the famous Coronelli globes offered to Louis XIV. -

Models for Earth and Maps

Earth Models and Maps James R. Clynch, Naval Postgraduate School, 2002 I. Earth Models Maps are just a model of the world, or a small part of it. This is true if the model is a globe of the entire world, a paper chart of a harbor or a digital database of streets in San Francisco. A model of the earth is needed to convert measurements made on the curved earth to maps or databases. Each model has advantages and disadvantages. Each is usually in error at some level of accuracy. Some of these error are due to the nature of the model, not the measurements used to make the model. Three are three common models of the earth, the spherical (or globe) model, the ellipsoidal model, and the real earth model. The spherical model is the form encountered in elementary discussions. It is quite good for some approximations. The world is approximately a sphere. The sphere is the shape that minimizes the potential energy of the gravitational attraction of all the little mass elements for each other. The direction of gravity is toward the center of the earth. This is how we define down. It is the direction that a string takes when a weight is at one end - that is a plumb bob. A spirit level will define the horizontal which is perpendicular to up-down. The ellipsoidal model is a better representation of the earth because the earth rotates. This generates other forces on the mass elements and distorts the shape. The minimum energy form is now an ellipse rotated about the polar axis. -

The History of Cartography, Volume Six: Cartography in the Twentieth Century

The AAG Review of Books ISSN: (Print) 2325-548X (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rrob20 The History of Cartography, Volume Six: Cartography in the Twentieth Century Jörn Seemann To cite this article: Jörn Seemann (2016) The History of Cartography, Volume Six: Cartography in the Twentieth Century, The AAG Review of Books, 4:3, 159-161, DOI: 10.1080/2325548X.2016.1187504 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/2325548X.2016.1187504 Published online: 07 Jul 2016. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 312 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rrob20 The AAG Review OF BOOKS The History of Cartography, Volume Six: Cartography in the Twentieth Century Mark Monmonier, ed. Chicago, document how all cultures of all his- IL: University of Chicago Press, torical periods represented the world 2015. 1,960 pp., set of 2 using maps” (Woodward 2001, 28). volumes, 805 color plates, What started as a chat on a relaxed 119 halftones, 242 line drawings, walk by these two authors in Devon, England, in May 1977 developed into 61 tables. $500.00 cloth (ISBN a monumental historia cartographica, 978-0-226-53469-5). a cartographic counterpart of Hum- boldt’s Kosmos. The project has not Reviewed by Jörn Seemann, been finished yet, as the volumes on Department of Geography, Ball the eighteenth and nineteenth cen- State University, Muncie, IN. tury are still in preparation, and will probably need a few more years to be published. -

Exploring the Reasons for the Seasons Using Google Earth, 3D Models, and Plots

International Journal of Digital Earth ISSN: 1753-8947 (Print) 1753-8955 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/tjde20 Exploring the reasons for the seasons using Google Earth, 3D models, and plots Declan G. De Paor, Mladen M. Dordevic, Paul Karabinos, Stephen Burgin, Filis Coba & Steven J. Whitmeyer To cite this article: Declan G. De Paor, Mladen M. Dordevic, Paul Karabinos, Stephen Burgin, Filis Coba & Steven J. Whitmeyer (2016): Exploring the reasons for the seasons using Google Earth, 3D models, and plots, International Journal of Digital Earth, DOI: 10.1080/17538947.2016.1239770 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17538947.2016.1239770 © 2016 The Author(s). Published by Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group Published online: 21 Oct 2016. Submit your article to this journal View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=tjde20 Download by: [141.105.107.244] Date: 21 October 2016, At: 09:31 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF DIGITAL EARTH, 2016 http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17538947.2016.1239770 Exploring the reasons for the seasons using Google Earth, 3D models, and plots Declan G. De Paora , Mladen M. Dordevicb , Paul Karabinosc , Stephen Burgind , Filis Cobae and Steven J. Whitmeyerb aDepartments of Physics and Ocean, Earth, and Atmospheric Sciences, Old Dominion University, Norfolk, VA, USA; bDepartment of Geology and Environmental Science, James Madison University, Harrisonburg, VA, USA; cDepartment of Geosciences, Williams College, Williamstown, MA, USA; dDepartment of Curriculum and Instruction, University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, AR, USA; eDepartment of Physics, Old Dominion University, Norfolk, VA, USA ABSTRACT ARTICLE HISTORY Public understanding of climate and climate change is of broad societal Received 7 May 2016 importance. -

The Chandelier Model by Richard Thompson on April 27Th, 1976

September 2008 The Chandelier Model by Richard Thompson On April 27th, 1976, Srila Prabhupada wrote a letter to Svarupa Damodara Das discussing the universe as described in the 5th Canto of the Srimad Bhagavatam. He asked his disciples with Ph.D’s to study the 5th Canto with the aim of making a model of the universe for a Vedic Planetarium. In this essay I will outline how such a model could be designed. This model has been called the “chandelier model” since it hangs down from a point of suspension situated on the ceiling above it. Srila Prabhupada said, “My final decision is that the universe is just like a tree, with root upwards. Just as a tree has branches and leaves so the universe is also composed of planets which are fixed up in the tree like the leaves, flowers, fruits, etc. of the tree. The pivot is the pole star, and the whole tree is rotating on this pivot. Mount Sumeru is the center, trunk, and is like a steep hill... The tree is turning and therefore, all the branches and leaves turn with the tree. The planets have their fixed orbits, but still they are turning with the turning of the great tree. There are pathways leading from one planet to another made of gold, copper, etc., and these are like the branches. Distances are also described in the 5th Canto just how far one planet is from another. We can see that at night, how the whole planetary system is turning around, the pole star being the pivot.