Knowing and Decorating the World Illustrations and Textual Descriptions in the Maps of the Fourth Edition of the Mercator-Hondius Atlas (1613)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Catalogue Summer 2012

JONATHAN POTTER ANTIQUE MAPS CATALOGUE SUMMER 2012 INTRODUCTION 2012 was always going to be an exciting year in London and Britain with the long- anticipated Queen’s Jubilee celebrations and the holding of the Olympic Games. To add to this, Jonathan Potter Ltd has moved to new gallery premises in Marylebone, one of the most pleasant parts of central London. After nearly 35 years in Mayfair, the move north of Oxford Street seemed a huge step to take, but is only a few minutes’ walk from Bond Street. 52a George Street is set in an attractive area of good hotels and restaurants, fine Georgian residential properties and interesting retail outlets. Come and visit us. Our summer catalogue features a fascinating mixture of over 100 interesting, rare and decorative maps covering a period of almost five hundred years. From the fifteenth century incunable woodcut map of the ancient world from Schedels’ ‘Chronicarum...’ to decorative 1960s maps of the French wine regions, the range of maps available to collectors and enthusiasts whether for study or just decoration is apparent. Although the majority of maps fall within the ‘traditional’ definition of antique, we have included a number of twentieth and late ninteenth century publications – a significant period in history and cartography which we find fascinating and in which we are seeing a growing level of interest and appreciation. AN ILLUSTRATED SELECTION OF ANTIQUE MAPS, ATLASES, CHARTS AND PLANS AVAILABLE FROM We hope you find the catalogue interesting and please, if you don’t find what you are looking for, ask us - we have many, many more maps in stock, on our website and in the JONATHAN POTTER LIMITED gallery. -

A History of the World in Twelve Maps

Book Review / A History of the World in Twelve Maps A History of the World in Twelve Maps Author Jerry Brotton Renaissance Studies at Queen Mary University of London, UK Review of International Geographical Education Online ©RIGEO, 8(3), Winter 2018 Reviewer Niyazi KAYA1 National Ministry of Education, Ankara, TURKEY Publisher: Allen Lane Publication Year: 2012 Edition: First Edition Pages: 514 + xviii Price: £32.99 ISBN: 978-0-141-03493-5 Jerry Brotton is Professor of Renaissance Studies at Queen Mary University of London. In his recent work Jerry Brotton, as a leading expert in the history of maps and Renaissance cartography, presents the histories of twelve maps belonging to different eras from the mystical representations of ancient times to Google Earth. He examines the stories of these twelve maps as having important roles in the context of regional and global perspectives of past and today's world. His book is an interesting and significant contribution to the interdisciplinary approach between history and geography. In addition to the twelve maps, thirty four figures and fifty six illustrations are included in this book, which aims to tell history through maps. All of the maps chosen by the author should not be regarded as the best ones of their times. Conversely, many of them were heavily criticized at the moment of their completion. Some maps were neglected at the time or subsequently dismissed as outdated or obscure. The author stresses that all the maps he analyzed in detail bear witness that one way of trying to understand the histories of our world is by exploring how the spaces within it are mapped (p.16). -

Neuzugänge Zur Stuttgarter Antiquariatsmesse

KATALOG CCXXV 2020 INTERESSANTE NEUZUGÄNGE ZUR STUTTGARTER ANTIQUARIATSMESSE ANTIQUARIAT CLEMENS PAULUSCH GmbH ANTIQUARIAT NIKOLAUS STRUCK VORWORT INHALT Liebe Kunden, Kollegen und Freunde, Aus dem Messekatalog 1 - 12 die Stuttgarter Antiquariatsmesse, seit Jahren der Auftakt des Antiquariatsjahres, wirft ihren Schatten voraus. Zur Messe erscheint Landkarten 13 - 212 dieses Jahr ein Katalog mit 600 Neuzugängen. Selbstverständlich werden wir, wie auch die Jahre zuvor, mit einer Stadtansichten 213 - 492 weit größeren Auswahl an Stadtansichten und Landkarten aufwarten können. Da wir nach Stuttgart nur eine Auswahl mitnehmen und Dekorative Grafik 493 - 581 präsentieren können, bitten wir Sie, sollten Sie spezielle Objekte aus unserem Bestand sehen wollen, uns zuvor zu benachrichtigen. Bücher 582 - 600 Die in diesem Katalog verzeichneten Blätter und Bücher sind mit Ausnahme der Nummern 1-12 vor der Messe bestellbar, denn diese Objekte sind unser Beitrag für den offiziellen Messekatalog. Allgemeine Geschäfts- Diesen Katalog finden Sie auf der Homepage der Stuttgarter und Lieferbedingungen Antiquariatsmesse (http://www.stuttgarter-antiquariatsmesse.de) und sowie die Widerrufsbelehrung können ihn auch über den Verband Deutscher Antiquare beziehen. finden Sie auf der letzten Seite. Wir möchten Sie herzlich einladen, uns auf der Messe zu besuchen, Sie finden uns aufStand 6. Ort: Württembergischer Kunstverein, Schlossplatz 2, Stuttgart Lieferbare Kataloge Öffnungszeiten: Freitag, 24. Januar: 12 bis 19.30 Uhr Samstag, 25. Januar: 11 bis 18 Uhr Katalog 200 Sonntag, 26. Januar: 11 bis 17 Uhr Berlin Rosenberg (31 Nummern) Eintrittspreis: 10 Euro (Einladungen für freien Eintritt Katalog 217 senden wir Ihnen gerne zu) Bella Italia und Felix Austria (800 Nummern) Nun wünschen wir Ihnen viel Spaß beim Lesen und Stöbern in diesem Katalog, Katalog 219 Ihr Clemens Paulusch Deutschland Teil 6: Gesamt und ehemals dt. -

The History of Cartography, Volume 3

THE HISTORY OF CARTOGRAPHY VOLUME THREE Volume Three Editorial Advisors Denis E. Cosgrove Richard Helgerson Catherine Delano-Smith Christian Jacob Felipe Fernández-Armesto Richard L. Kagan Paula Findlen Martin Kemp Patrick Gautier Dalché Chandra Mukerji Anthony Grafton Günter Schilder Stephen Greenblatt Sarah Tyacke Glyndwr Williams The History of Cartography J. B. Harley and David Woodward, Founding Editors 1 Cartography in Prehistoric, Ancient, and Medieval Europe and the Mediterranean 2.1 Cartography in the Traditional Islamic and South Asian Societies 2.2 Cartography in the Traditional East and Southeast Asian Societies 2.3 Cartography in the Traditional African, American, Arctic, Australian, and Pacific Societies 3 Cartography in the European Renaissance 4 Cartography in the European Enlightenment 5 Cartography in the Nineteenth Century 6 Cartography in the Twentieth Century THE HISTORY OF CARTOGRAPHY VOLUME THREE Cartography in the European Renaissance PART 1 Edited by DAVID WOODWARD THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS • CHICAGO & LONDON David Woodward was the Arthur H. Robinson Professor Emeritus of Geography at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London © 2007 by the University of Chicago All rights reserved. Published 2007 Printed in the United States of America 1615141312111009080712345 Set ISBN-10: 0-226-90732-5 (cloth) ISBN-13: 978-0-226-90732-1 (cloth) Part 1 ISBN-10: 0-226-90733-3 (cloth) ISBN-13: 978-0-226-90733-8 (cloth) Part 2 ISBN-10: 0-226-90734-1 (cloth) ISBN-13: 978-0-226-90734-5 (cloth) Editorial work on The History of Cartography is supported in part by grants from the Division of Preservation and Access of the National Endowment for the Humanities and the Geography and Regional Science Program and Science and Society Program of the National Science Foundation, independent federal agencies. -

General Index

General Index Italic page numbers refer to illustrations. Authors are listed in ical Index. Manuscripts, maps, and charts are usually listed by this index only when their ideas or works are discussed; full title and author; occasionally they are listed under the city and listings of works as cited in this volume are in the Bibliograph- institution in which they are held. CAbbas I, Shah, 47, 63, 65, 67, 409 on South Asian world maps, 393 and Kacba, 191 "Jahangir Embracing Shah (Abbas" Abywn (Abiyun) al-Batriq (Apion the in Kitab-i balJriye, 232-33, 278-79 (painting), 408, 410, 515 Patriarch), 26 in Kitab ~urat ai-arc!, 169 cAbd ai-Karim al-Mi~ri, 54, 65 Accuracy in Nuzhat al-mushtaq, 169 cAbd al-Rabman Efendi, 68 of Arabic measurements of length of on Piri Re)is's world map, 270, 271 cAbd al-Rabman ibn Burhan al-Maw~ili, 54 degree, 181 in Ptolemy's Geography, 169 cAbdolazlz ibn CAbdolgani el-Erzincani, 225 of Bharat Kala Bhavan globe, 397 al-Qazwlni's world maps, 144 Abdur Rahim, map by, 411, 412, 413 of al-BlrunI's calculation of Ghazna's on South Asian world maps, 393, 394, 400 Abraham ben Meir ibn Ezra, 60 longitude, 188 in view of world landmass as bird, 90-91 Abu, Mount, Rajasthan of al-BlrunI's celestial mapping, 37 in Walters Deniz atlast, pl.23 on Jain triptych, 460 of globes in paintings, 409 n.36 Agapius (Mabbub) religious map of, 482-83 of al-Idrisi's sectional maps, 163 Kitab al- ~nwan, 17 Abo al-cAbbas Abmad ibn Abi cAbdallah of Islamic celestial globes, 46-47 Agnese, Battista, 279, 280, 282, 282-83 Mu\:lammad of Kitab-i ba/Jriye, 231, 233 Agnicayana, 308-9, 309 Kitab al-durar wa-al-yawaqft fi 11m of map of north-central India, 421, 422 Agra, 378 n.145, 403, 436, 448, 476-77 al-ra~d wa-al-mawaqft (Book of of maps in Gentil's atlas of Mughal Agrawala, V. -

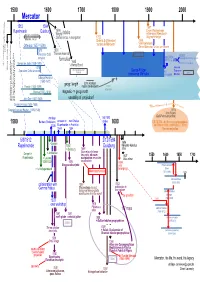

Visio-MERCATOR ENG2.Vsd

1500 1600 1700 1800 1900 2000 Mercator 1512 1594 1897 Rupelmonde Duisburg 1599 tables Lt-gen Wauwermans Italian composite Wright tables article about Mercator in Certain erros in navigation 1752 Biographie belge atlases IATO 1869 middle 15th Century Diderot & d’Alembert “cartes de Mercator” Van Raemdonck Ortelius (1527-1598) Gérard Mercator, sa vie, son oeuvre printing 1570 1600 Theatrum Orbis Thomas Harrriot projection MGRS terrarum 1772 1825 1914 post WWI military grid reference system formulas Johan Lambert Carl Friedrich Gauss Johann Krüger NATO UTM Gerard de Jode (1509-1591) 1645 transverse Mercator transverse Mercator transverse Mercator civil reference system fall of Constantinople Henry Bond 1578 (sphere) (ellipsoid) (ellipsoid) Universal 1492 end of Reconquista Mercatorprojection Transverse Speculum Orbis terrarum formula Gauss-Krüger 1942 grid transverse Mercator developped Mercator Judocus Hondius (1563-1612) + geogr. length John Harrison Plantijn (1520-1589) marine timekeepers use of projection Moretus (1543-1610) magnetic <> geogr north John Dee (1527-1608) useability of projection? 1488 Bartholomeus Dias rounded Cape of Good Hope 1492 Columbus ‘America’ discovered 1498 Vasco da Gama reached India via Africa 1519 – 1522 Magellan around the world Gemma Frisius (1508-1555) 1904 criticism + -- Gaspard van der Heyden (1496-1549) 1974 Arne Peters (Gall-Peters-projection) mariage 5/5/1590 1500 Barbara Shellekens arrested in met Ortelius stroke 1600 CRITICISM - but from non-cartographers - 1536 Rupelmonde in Frankfurt on ethnocentrism, -

Antique Maps and the Study Ok Caribbean Prehistory

ANTIQUE MAPS AND THE STUDY OK CARIBBEAN PREHISTORY Stephen D. Glazier In this presentation I will explore possible uses of sixteenth and seventeenth century maps for the study of Caribbean prehistory and protohistory. Several considerations entered into my choice of maps, the foremost of which was accessibility. Maps covered in this present ation are readily available through private collections, the map trade, museums, libraries and in facsimile. Accuracy was a secondary consideration. The succession of New World maps is not a general progression from the speculative to the scientific, and at times, as Bernardo Vega demonstrated in his mono graph on the caciques of Hispaniola, early maps may be more accurate than later editions. Professor Vega found that the map of Morales (1508) was far superior to later maps and that it was far more accurate than the published accounts of Las Casas and Oveido (Vega 1980: 22). Tooley (1978: xv), the foremost authority on antique maps, claims that seventeenth century maps are much more "decorative" than sixteenth century maps. Whenever mapmakers of the sixteenth century encountered gaps in their knowledge of an area, they simply left that area blank or added a strapwork cartouche. Seventeenth century map- makers, on the other hand, felt obliged to fill in all gaps by provid ing misinformation of depicting native ways of life and flora and fauna. Sea monsters and cannibals were commonly used. All mapmakers claimed to base their works on the "latest" inform ation; however, it is my contention that maps are essentially conserv ative documents. A number of factors militated against the rapid assimilation of new data. -

Early & Rare World Maps, Atlases & Rare Books

19219a_cover.qxp:Layout 1 5/10/11 12:48 AM Page 1 EARLY & RARE WORLD MAPS, ATLASES & RARE BOOKS Mainly from a Private Collection MARTAYAN LAN CATALOGUE 70 EAST 55TH STREET • NEW YORK, NEW YORK 10022 45 To Order or Inquire: Telephone: 800-423-3741 or 212-308-0018 Fax: 212-308-0074 E-Mail: [email protected] Website: www.martayanlan.com Gallery Hours: Monday through Friday 9:30 to 5:30 Saturday and Evening Hours by Appointment. We welcome any questions you might have regarding items in the catalogue. Please let us know of specific items you are seeking. We are also happy to discuss with you any aspect of map collecting. Robert Augustyn Richard Lan Seyla Martayan James Roy Terms of Sale: All items are sent subject to approval and can be returned for any reason within a week of receipt. All items are original engrav- ings, woodcuts or manuscripts and guaranteed as described. New York State residents add 8.875 % sales tax. Personal checks, Visa, MasterCard, American Express, and wire transfers are accepted. To receive periodic updates of recent acquisitions, please contact us or register on our website. Catalogue 45 Important World Maps, Atlases & Geographic Books Mainly from a Private Collection the heron tower 70 east 55th street new york, new york 10022 Contents Item 1. Isidore of Seville, 1472 p. 4 Item 2. C. Ptolemy, 1478 p. 7 Item 3. Pomponius Mela, 1482 p. 9 Item 4. Mer des hystoires, 1491 p. 11 Item 5. H. Schedel, 1493, Nuremberg Chronicle p. 14 Item 6. Bergomensis, 1502, Supplementum Chronicum p. -

Women in Vermeer's Home Mimesis and Ideation

Women in Vermeer's home Mimesis and ideation H. Perry Chapman Johannes Vermeer (1632-1675) is widely regarded as a definer of the Dutch detail domestic interior at its height in the 1660s. Vet comparison ofhis oeuvre to Johannes Vermeer, The art ofpainting, those of his contemporaries Pieter de Hooch (1629-1684), Jan Steen (1626 c. 1666-1667, oi! on canvas, 120 x 100 cm. Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna 1679), Gabriel Metsu (1629-1669), Nicolaes Maes (1634-1693), and others, (photo: museum). reveals that his pictures of home life are unusual in their omission ofwhat were quickly becoming stock features of the imagery of domesticity. The domestic ideal that flourished in the art ofmid-seventeenth century Holland entailed preparation for marriage, homemaking, housewifery, nurturing, and the virtues of family life, values that were celebrated, too, in popular household manuals ofwhich Jacob Cats' Houwelyck is the best known. 1 But Vermeer painted no families, the stock and trade ofJan Steen, master ofboth the dissolute household (fig. 11) and the harmonious, pious family saying grace. 2 Nor did he paint mothers tending to children in the absence of fathers, a popular theme that increasingly cast the home and child rearing as mothers' moral domain, which was the subject ofsome ofthe most engaging pictures by Pieter de Hooch, his Delft contemporary (see fig. 17).3 For that matter, with two small and somewhat anonymous exceptions (see fig. I), Vermeer painted no children, which is noteworthy not so much for its con trast with his own full household but because it shows him going against a pictorial grain ofendearing sentimentality.4 Also unusual in Vermeer's image of domesticity is the absence of essential furnishings and accoutrements of home life. -

From the Old Ages to Mercator

14 The World Image in Maps – From the Old Ages to Mercator Mirjanka Lechthaler Institute of Geoinformation and Cartography Vienna University of Technology, Austria Abstract Studying the Australian aborigines’ ‘dreamtime’ maps or engravings from Dutch cartographers of the 16 th century, one can lose oneself in their beauty. Casually, cartography is a kind of art. Visualization techniques, precision and compliance with reality are of main interest. The centuries of great expeditions led to today’s view and mapping of the world. This chapter gives an overview on the milestones in the history of cartography, from the old ages to Mercator’s map collections. Each map presented is a work of art, which acts as a substitute for its era, allowing us to re-live the circumstances at that time. 14.1 Introduction Long before people were able to write, maps have been used to visualise reality or fantasy. Their content in \ uenced how people saw the world. From studying maps conclusions can be drawn about how visualized regions are experienced, imagined, or meant to be perceived. Often this is in \ uenced by social and political objectives. Cartography is an essential instrument in mapping and therefore preserving cultural heritage. Map contents are expressed by means of graphical language. Only techniques changed – from cuneiform writing to modern digital techniques. From the begin- nings of cartography until now, this language remained similar: clearly perceptible graphics that represented real world objects. The chapter features the brief and concise history of the appearance and develop- ment of topographic representations from Mercator’s time (1512–1594), which was an important period for the development of cartography. -

WILLIAM R. TALBOT FINE ART, ANTIQUE MAPS & PRINTS 505-982-1559 • [email protected] • for Purchases, Please Call Or Email

ILLIAM R TALT FIE ART, ATIE MAPS PRITS 129 West San Francisco Street • P. O. Box 2757, Santa Fe, New Mexico 87504 505-982-1559 • [email protected] • www.williamtalbot.com FALL 2019 Abraham Ortelius’s FIRST EDITION WORLD MAP The present map is a depiction of the world from the Age of Discovery and the earliest edition of Abraham Ortelius’s famous world map rendered in magnificent color. Ortelius was a great compiler of newly discovered geographical facts and information. His New World mapping is also a study in early conjecture, including a generous northwest passage below the Terra Septentrionalis Incognita, and a projection of the St. Lawrence reaching to the middle of the continent. Ortelius’s map includes Terra Australis Nondum Cognita, reflecting the misconception held at the time of a massive southern continent, that incorporates Tierra del Fuego in this southern polar region rather than in South America. The relatively unknown regions across Northeast Asia distort the outline of Japan considerably. In the North Atlantic, the outline of Scandinavia is skewed, and Greenland appears very close to Abraham Ortelius (1528–1598). “Typus Orbis Terrarum,” (Antwerp: 1570). First Edition. Published in the Latin editions of Theatrum Orbis Terrarum. Double- North America. Ortelius published his world maps page copperplate engraving with full hand color and some original color. Signed by in his Theatrum Orbis Terrarum, considered to be engraver l.r. “Franciscus (Frans) Hogenberg”. Latin text, verso: “Orbis Terrarum.” the first modern atlas, with 70 copper engravings and “I”. 13 3/32 x 19 7/16” to neatline. Sheet: 15 9/16 x 20 3/4”. -

=Ë*F7"Lt-.,., ..Re, .Ê'

THE UNIVERSITY OF MANITOBA MERCATOR'S CHANGING CONCEPT OF THE NATURE OF THE NORTH POLE by URTE E. DE REYES A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMEI{TS FOR THE DEGREE \J-r MASTER OF ARTS HISTORY DEPARTMENT I{II\ll{IPEG, IVTAN ITOBA october L973 '' I '' ' ' t. *¡.--\- ,f =Ë*F7"lt-.,., ..re, .ê' ÀC Kl'i O-i',iL E D GE ilrä t'i T S I v¡ould lilce r'irsL 'bo Lhank si-ucerely P::ofessor i{enry Heller for the unflagging ínterest he has taken Ín my worl< and for his valuable advice and consiructive cri.bicism, I am very gratefulu Loo, to Professor John L, FÍnlay tdho,without thought for his own time or trouble, vJas always readl'to help arlcl encourage me in my t"¡ork' I am parLicularly 'inoebL.ed to Professor iriarvin K. singleton r,¿ho introduced ne to the study of the historl' of ideas anci guicìed me to I'1e::cator the humanisL" To Doctor RÕman Drazniorvsky, i,llap Curator of the ,\nrerican Geographícal Society of l{er"¡ York, T v'rísh to the aclvíce he has givet: me from e,LÈ/r!rJUêr¿rrrêqq ^.'Jm\/ oratiLude for his greaL store of carLographical knor,vledge and for allovring me to photograph the l"lercator maps ø And-fwanttotlranktire¡l'mericanGeographícal Society of i$er,v York for giving me access to their valuable 'l i l¡r¡rr¡ ;¡n¡*-^- -.tcl!',rnîh \-uJ!Euç¡vrf^^1 I a¡ì-.ì nn ¿v!fnr mr¡ rêsea-I: Ch" I also tvould like to avail rnyself of this opportu-nity to extend my síncere appreciation to all the members of the ui cl-nrr¡ a€ {-heIÇ ur¡r v l'.anicoi:a for !/eflô, v s!-r+-mon.t- n.í: i-r-L Þ UUI ) V¿ uI Tlniversitv of having guicìecl and encouraged me in the pursuit of my >^l-,.-l; LLlLlI(JÐ ^A @ tll TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF FIGURES.