Cartographer's Experience of Time in the Mercator-Hondius Atlas (1606

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![Or Later, but Before 1650] 687X868mm. Copper Engraving On](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3632/or-later-but-before-1650-687x868mm-copper-engraving-on-163632.webp)

Or Later, but Before 1650] 687X868mm. Copper Engraving On

60 Willem Janszoon BLAEU (1571-1638). Pascaarte van alle de Zécuften van EUROPA. Nieulycx befchreven door Willem Ianfs. Blaw. Men vintfe te coop tot Amsterdam, Op't Water inde vergulde Sonnewÿser. [Amsterdam, 1621 or later, but before 1650] 687x868mm. Copper engraving on parchment, coloured by a contemporary hand. Cropped, as usual, on the neat line, to the right cut about 5mm into the printed area. The imprint is on places somewhat weaker and /or ink has been faded out. One small hole (1,7x1,4cm.) in lower part, inland of Russia. As often, the parchment is wavy, with light water staining, usual staining and surface dust. First state of two. The title and imprint appear in a cartouche, crowned by the printer's mark of Willem Jansz Blaeu [INDEFESSVS AGENDO], at the center of the lower border. Scale cartouches appear in four corners of the chart, and richly decorated coats of arms have been engraved in the interior. The chart is oriented to the west. It shows the seacoasts of Europe from Novaya Zemlya and the Gulf of Sydra in the east, and the Azores and the west coast of Greenland in the west. In the north the chart extends to the northern coast of Spitsbergen, and in the south to the Canary Islands. The eastern part of the Mediterranean id included in the North African interior. The chart is printed on parchment and coloured by a contemporary hand. The colours red and green and blue still present, other colours faded. An intriguing line in green colour, 34 cm long and about 3mm bold is running offshore the Norwegian coast all the way south of Greenland, and closely following Tara Polar Arctic Circle ! Blaeu's chart greatly influenced other Amsterdam publisher's. -

Visio-MERCATOR ENG2.Vsd

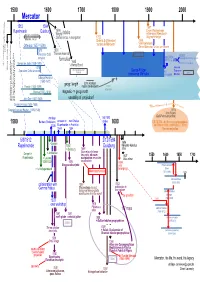

1500 1600 1700 1800 1900 2000 Mercator 1512 1594 1897 Rupelmonde Duisburg 1599 tables Lt-gen Wauwermans Italian composite Wright tables article about Mercator in Certain erros in navigation 1752 Biographie belge atlases IATO 1869 middle 15th Century Diderot & d’Alembert “cartes de Mercator” Van Raemdonck Ortelius (1527-1598) Gérard Mercator, sa vie, son oeuvre printing 1570 1600 Theatrum Orbis Thomas Harrriot projection MGRS terrarum 1772 1825 1914 post WWI military grid reference system formulas Johan Lambert Carl Friedrich Gauss Johann Krüger NATO UTM Gerard de Jode (1509-1591) 1645 transverse Mercator transverse Mercator transverse Mercator civil reference system fall of Constantinople Henry Bond 1578 (sphere) (ellipsoid) (ellipsoid) Universal 1492 end of Reconquista Mercatorprojection Transverse Speculum Orbis terrarum formula Gauss-Krüger 1942 grid transverse Mercator developped Mercator Judocus Hondius (1563-1612) + geogr. length John Harrison Plantijn (1520-1589) marine timekeepers use of projection Moretus (1543-1610) magnetic <> geogr north John Dee (1527-1608) useability of projection? 1488 Bartholomeus Dias rounded Cape of Good Hope 1492 Columbus ‘America’ discovered 1498 Vasco da Gama reached India via Africa 1519 – 1522 Magellan around the world Gemma Frisius (1508-1555) 1904 criticism + -- Gaspard van der Heyden (1496-1549) 1974 Arne Peters (Gall-Peters-projection) mariage 5/5/1590 1500 Barbara Shellekens arrested in met Ortelius stroke 1600 CRITICISM - but from non-cartographers - 1536 Rupelmonde in Frankfurt on ethnocentrism, -

Ortelius's Typus Orbis Terrarum (1570)

Ortelius’s Typus Orbis Terrarum (1570) by Giorgio Mangani (Ancona, Italy) Paper presented at the 18th International Conference for the History of Cartography (Athens, 11-16th July 1999), in the "Theory Session", with Lucia Nuti (University of Pisa), Peter van der Krogt (University of Uthercht), Kess Zandvliet (Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam), presided by Dennis Reinhartz (University of Texas at Arlington). I tried to examine this map according to my recent studies dedicated to Abraham Ortelius,1 trying to verify the deep meaning that it could have in his work of geographer and intellectual, committed in a rather wide religious and political programme. Ortelius was considered, in the scientific and intellectual background of the XVIth century Low Countries, as a model of great morals in fact, he was one of the most famous personalities of Northern Europe; he was a scholar, a collector, a mystic, a publisher, a maps and books dealer and he was endowed with a particular charisma, which seems to have influenced the work of one of the best artist of the time, Pieter Bruegel the Elder. Dealing with the deep meaning of Ortelius’ atlas, I tried some other time to prove that the Theatrum, beyond its function of geographical documentation and succesfull publishing product, aimed at a political and theological project which Ortelius shared with the background of the Familist clandestine sect of Antwerp (the Family of Love). In short, the fundamentals of the familist thought focused on three main points: a) an accentuated sensibility towards a mysticism close to the so called devotio moderna, that is to say an inner spirituality searching for a direct relation with God. -

Early & Rare World Maps, Atlases & Rare Books

19219a_cover.qxp:Layout 1 5/10/11 12:48 AM Page 1 EARLY & RARE WORLD MAPS, ATLASES & RARE BOOKS Mainly from a Private Collection MARTAYAN LAN CATALOGUE 70 EAST 55TH STREET • NEW YORK, NEW YORK 10022 45 To Order or Inquire: Telephone: 800-423-3741 or 212-308-0018 Fax: 212-308-0074 E-Mail: [email protected] Website: www.martayanlan.com Gallery Hours: Monday through Friday 9:30 to 5:30 Saturday and Evening Hours by Appointment. We welcome any questions you might have regarding items in the catalogue. Please let us know of specific items you are seeking. We are also happy to discuss with you any aspect of map collecting. Robert Augustyn Richard Lan Seyla Martayan James Roy Terms of Sale: All items are sent subject to approval and can be returned for any reason within a week of receipt. All items are original engrav- ings, woodcuts or manuscripts and guaranteed as described. New York State residents add 8.875 % sales tax. Personal checks, Visa, MasterCard, American Express, and wire transfers are accepted. To receive periodic updates of recent acquisitions, please contact us or register on our website. Catalogue 45 Important World Maps, Atlases & Geographic Books Mainly from a Private Collection the heron tower 70 east 55th street new york, new york 10022 Contents Item 1. Isidore of Seville, 1472 p. 4 Item 2. C. Ptolemy, 1478 p. 7 Item 3. Pomponius Mela, 1482 p. 9 Item 4. Mer des hystoires, 1491 p. 11 Item 5. H. Schedel, 1493, Nuremberg Chronicle p. 14 Item 6. Bergomensis, 1502, Supplementum Chronicum p. -

THE CONSTELLATION MUSCA, the FLY Musca Australis (Latin: Southern Fly) Is a Small Constellation in the Deep Southern Sky

THE CONSTELLATION MUSCA, THE FLY Musca Australis (Latin: Southern Fly) is a small constellation in the deep southern sky. It was one of twelve constellations created by Petrus Plancius from the observations of Pieter Dirkszoon Keyser and Frederick de Houtman and it first appeared on a 35-cm diameter celestial globe published in 1597 in Amsterdam by Plancius and Jodocus Hondius. The first depiction of this constellation in a celestial atlas was in Johann Bayer's Uranometria of 1603. It was also known as Apis (Latin: bee) for two hundred years. Musca remains below the horizon for most Northern Hemisphere observers. Also known as the Southern or Indian Fly, the French Mouche Australe ou Indienne, the German Südliche Fliege, and the Italian Mosca Australe, it lies partly in the Milky Way, south of Crux and east of the Chamaeleon. De Houtman included it in his southern star catalogue in 1598 under the Dutch name De Vlieghe, ‘The Fly’ This title generally is supposed to have been substituted by La Caille, about 1752, for Bayer's Apis, the Bee; but Halley, in 1679, had called it Musca Apis; and even previous to him, Riccioli catalogued it as Apis seu Musca. Even in our day the idea of a Bee prevails, for Stieler's Planisphere of 1872 has Biene, and an alternative title in France is Abeille. When the Northern Fly was merged with Aries by the International Astronomical Union (IAU) in 1929, Musca Australis was given its modern shortened name Musca. It is the only official constellation depicting an insect. Julius Schiller, who redrew and named all the 88 constellations united Musca with the Bird of Paradise and the Chamaeleon as mother Eve. -

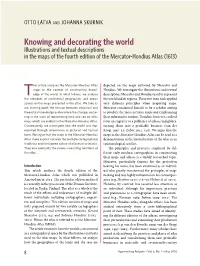

Knowing and Decorating the World Illustrations and Textual Descriptions in the Maps of the Fourth Edition of the Mercator-Hondius Atlas (1613)

OTTO LATVA AND JOHANNA SKURNIK Knowing and decorating the world Illustrations and textual descriptions in the maps of the fourth edition of the Mercator-Hondius Atlas (1613) his article analyses the Mercator-Hondius Atlas depicted on the maps authored by Mercator and maps in the context of constructing knowl- Hondius. We investigate the illustrations and textual Tedge of the world. In what follows, we analyse descriptions Mercator and Hondius used to represent the elem ents of continental geographies and ocean the world and its regions. These two men each applied spaces on the maps presented in the atlas. We take as very different principles when preparing maps: our starting point the tension between empirical and Mercator considered himself to be a scholar aiming theoretical knowledge and examine the changes occur- to produce the most accurate maps and emphasizing ring in the ways of representing land and sea on atlas their informative content. Hondius, however, evolved maps which are evident in the Mercator-Hondius Atlas. from an engraver to a publisher of atlases and globes, Consequently, we investigate how the world was rep- turning them into a profitable business (van der resented through information in pictorial and textual Krogt 1997: 35; Zuber 2011: 516). We argue that the form. We argue that the maps in the Mercator-Hondius maps in the Mercator-Hondius Atlas can be read as a Atlas make explicit not only the multiple cartographical demonstration of the layered nature of the atlas as an trad itions and the layered nature of atlases as artefacts. epistemological artefact. They also exemplify the various coexisting functions of The principles and practices employed by dif- the atlas. -

Development and Achievements of Dutch Northern and Arctic Cartography

ARCTIC’ VOL. 37, NO. 4 (DECEMBER 1984) P. 493.514 Development and Achievements of Dutch Northern and Arctic Cartography. in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth :Centuries GUNTER. SCHILDER* ther north, as far as the Shetlands the Faroes, in line with INTRODUCTION and the expansion of the Dutch .fishing and trading areas. The During the sixteenth and .seventeenth. centuries, the Dutch Thresmr contains a number of coastal viewsfrom the voyage made. a vital contribution to. the mapphg of the northern and around the North Capeas far as ‘‘Wardhuys”. Although there arctic regions, and their caPtographic work piayed a decisive is no mapofthis region, there is.a map of the coasts of Karelia part in expanding. the ,geographical .knowledgeof that time. and Russia to the east of the White Sea asfar as the Pechora, Amsterdam became the centre.of international map production accompanied by a text with instructionsfor navigation as far as and the map trade. Its Cartographers and publishers acquired Vaygach and Novaya Zemlya (Waghenaer, 1592:fo101-105). their knowledge partly from the results of expeditions fitted A coastal view.of the latter is also given.s The fact that Wag- out by theirfellow countrymen and, partlyfrom foreign henaer had access to original sources is shown by the inclusion voyages of discovery. This paper will describe the growing- in the Thresoor of the only known accountof Olivier Brunel’s Dutch..awarenessof .the northern and arctic regions. stage by voyage to-NovayaZemlya in 1584 (Waghenaer, ‘1592:P104).6 stage and region by region, with the aid of Dutch. maps. Anotherimportant document is WillemBiuentsz’s map of northern Scandinavia, which extends as faras the entrance to THE PROGRESS OF DUTCH KNOWLEDGE IN THE NORTH .the White Sea, and shows.al1 the reefs and shallows(Fig. -

Snake in the Clouds: a New Nearby Dwarf Galaxy in the Magellanic Bridge ∗ Sergey E

MNRAS 000, 1{21 (2018) Preprint 19 April 2018 Compiled using MNRAS LATEX style file v3.0 Snake in the Clouds: A new nearby dwarf galaxy in the Magellanic bridge ∗ Sergey E. Koposov,1;2 Matthew G. Walker,1 Vasily Belokurov,2;3 Andrew R. Casey,4;5 Alex Geringer-Sameth,y6 Dougal Mackey,7 Gary Da Costa,7 Denis Erkal8, Prashin Jethwa9, Mario Mateo,10, Edward W. Olszewski11 and John I. Bailey III12 1McWilliams Center for Cosmology, Carnegie Mellon University, 5000 Forbes Ave, 15213, USA 2Institute of Astronomy, University of Cambridge, Madingley road, CB3 0HA, UK 3Center for Computational Astrophysics, Flatiron Institute, 162 5th Avenue, New York, NY 10010, USA 4School of Physics and Astronomy, Monash University, Clayton 3800, Victoria, Australia 5Faculty of Information Technology, Monash University, Clayton 3800, Victoria, Australia 6Astrophysics Group, Physics Department, Imperial College London, Prince Consort Rd, London SW7 2AZ, UK 7Research School of Astronomy and Astrophysics, Australian National University, Canberra, ACT 2611, Australia 8Department of Physics, University of Surrey, Guildford, GU2 7XH, UK 9European Southern Observatory, Karl-Schwarzschild-Str. 2, 85748 Garching, Germany 10Department of Astronomy, University of Michigan, 311 West Hall, 1085 S University Avenue, Ann Arbor, MI 48109, USA 11Steward Observatory, The University of Arizona, 933 N. Cherry Avenue., Tucson, AZ 85721, USA 12Leiden Observatory, Leiden University, Niels Bohrweg 2, 2333 CA Leiden, The Netherlands Accepted XXX. Received YYY; in original form ZZZ ABSTRACT We report the discovery of a nearby dwarf galaxy in the constellation of Hydrus, between the Large and the Small Magellanic Clouds. Hydrus 1 is a mildy elliptical ultra-faint system with luminosity MV 4:7 and size 50 pc, located 28 kpc from the Sun and 24 kpc from the LMC. -

From the Old Ages to Mercator

14 The World Image in Maps – From the Old Ages to Mercator Mirjanka Lechthaler Institute of Geoinformation and Cartography Vienna University of Technology, Austria Abstract Studying the Australian aborigines’ ‘dreamtime’ maps or engravings from Dutch cartographers of the 16 th century, one can lose oneself in their beauty. Casually, cartography is a kind of art. Visualization techniques, precision and compliance with reality are of main interest. The centuries of great expeditions led to today’s view and mapping of the world. This chapter gives an overview on the milestones in the history of cartography, from the old ages to Mercator’s map collections. Each map presented is a work of art, which acts as a substitute for its era, allowing us to re-live the circumstances at that time. 14.1 Introduction Long before people were able to write, maps have been used to visualise reality or fantasy. Their content in \ uenced how people saw the world. From studying maps conclusions can be drawn about how visualized regions are experienced, imagined, or meant to be perceived. Often this is in \ uenced by social and political objectives. Cartography is an essential instrument in mapping and therefore preserving cultural heritage. Map contents are expressed by means of graphical language. Only techniques changed – from cuneiform writing to modern digital techniques. From the begin- nings of cartography until now, this language remained similar: clearly perceptible graphics that represented real world objects. The chapter features the brief and concise history of the appearance and develop- ment of topographic representations from Mercator’s time (1512–1594), which was an important period for the development of cartography. -

WILLIAM R. TALBOT FINE ART, ANTIQUE MAPS & PRINTS 505-982-1559 • [email protected] • for Purchases, Please Call Or Email

ILLIAM R TALT FIE ART, ATIE MAPS PRITS 129 West San Francisco Street • P. O. Box 2757, Santa Fe, New Mexico 87504 505-982-1559 • [email protected] • www.williamtalbot.com FALL 2019 Abraham Ortelius’s FIRST EDITION WORLD MAP The present map is a depiction of the world from the Age of Discovery and the earliest edition of Abraham Ortelius’s famous world map rendered in magnificent color. Ortelius was a great compiler of newly discovered geographical facts and information. His New World mapping is also a study in early conjecture, including a generous northwest passage below the Terra Septentrionalis Incognita, and a projection of the St. Lawrence reaching to the middle of the continent. Ortelius’s map includes Terra Australis Nondum Cognita, reflecting the misconception held at the time of a massive southern continent, that incorporates Tierra del Fuego in this southern polar region rather than in South America. The relatively unknown regions across Northeast Asia distort the outline of Japan considerably. In the North Atlantic, the outline of Scandinavia is skewed, and Greenland appears very close to Abraham Ortelius (1528–1598). “Typus Orbis Terrarum,” (Antwerp: 1570). First Edition. Published in the Latin editions of Theatrum Orbis Terrarum. Double- North America. Ortelius published his world maps page copperplate engraving with full hand color and some original color. Signed by in his Theatrum Orbis Terrarum, considered to be engraver l.r. “Franciscus (Frans) Hogenberg”. Latin text, verso: “Orbis Terrarum.” the first modern atlas, with 70 copper engravings and “I”. 13 3/32 x 19 7/16” to neatline. Sheet: 15 9/16 x 20 3/4”. -

=Ë*F7"Lt-.,., ..Re, .Ê'

THE UNIVERSITY OF MANITOBA MERCATOR'S CHANGING CONCEPT OF THE NATURE OF THE NORTH POLE by URTE E. DE REYES A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMEI{TS FOR THE DEGREE \J-r MASTER OF ARTS HISTORY DEPARTMENT I{II\ll{IPEG, IVTAN ITOBA october L973 '' I '' ' ' t. *¡.--\- ,f =Ë*F7"lt-.,., ..re, .ê' ÀC Kl'i O-i',iL E D GE ilrä t'i T S I v¡ould lilce r'irsL 'bo Lhank si-ucerely P::ofessor i{enry Heller for the unflagging ínterest he has taken Ín my worl< and for his valuable advice and consiructive cri.bicism, I am very gratefulu Loo, to Professor John L, FÍnlay tdho,without thought for his own time or trouble, vJas always readl'to help arlcl encourage me in my t"¡ork' I am parLicularly 'inoebL.ed to Professor iriarvin K. singleton r,¿ho introduced ne to the study of the historl' of ideas anci guicìed me to I'1e::cator the humanisL" To Doctor RÕman Drazniorvsky, i,llap Curator of the ,\nrerican Geographícal Society of l{er"¡ York, T v'rísh to the aclvíce he has givet: me from e,LÈ/r!rJUêr¿rrrêqq ^.'Jm\/ oratiLude for his greaL store of carLographical knor,vledge and for allovring me to photograph the l"lercator maps ø And-fwanttotlranktire¡l'mericanGeographícal Society of i$er,v York for giving me access to their valuable 'l i l¡r¡rr¡ ;¡n¡*-^- -.tcl!',rnîh \-uJ!Euç¡vrf^^1 I a¡ì-.ì nn ¿v!fnr mr¡ rêsea-I: Ch" I also tvould like to avail rnyself of this opportu-nity to extend my síncere appreciation to all the members of the ui cl-nrr¡ a€ {-heIÇ ur¡r v l'.anicoi:a for !/eflô, v s!-r+-mon.t- n.í: i-r-L Þ UUI ) V¿ uI Tlniversitv of having guicìecl and encouraged me in the pursuit of my >^l-,.-l; LLlLlI(JÐ ^A @ tll TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF FIGURES. -

Map Projections

Map Projections Chapter 4 Map Projections What is map projection? Why are map projections drawn? What are the different types of projections? Which projection is most suitably used for which area? In this chapter, we will seek the answers of such essential questions. MAP PROJECTION Map projection is the method of transferring the graticule of latitude and longitude on a plane surface. It can also be defined as the transformation of spherical network of parallels and meridians on a plane surface. As you know that, the earth on which we live in is not flat. It is geoid in shape like a sphere. A globe is the best model of the earth. Due to this property of the globe, the shape and sizes of the continents and oceans are accurately shown on it. It also shows the directions and distances very accurately. The globe is divided into various segments by the lines of latitude and longitude. The horizontal lines represent the parallels of latitude and the vertical lines represent the meridians of the longitude. The network of parallels and meridians is called graticule. This network facilitates drawing of maps. Drawing of the graticule on a flat surface is called projection. But a globe has many limitations. It is expensive. It can neither be carried everywhere easily nor can a minor detail be shown on it. Besides, on the globe the meridians are semi-circles and the parallels 35 are circles. When they are transferred on a plane surface, they become intersecting straight lines or curved lines. 2021-22 Practical Work in Geography NEED FOR MAP PROJECTION The need for a map projection mainly arises to have a detailed study of a 36 region, which is not possible to do from a globe.