=Ë*F7"Lt-.,., ..Re, .Ê'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Visio-MERCATOR ENG2.Vsd

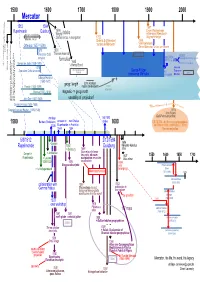

1500 1600 1700 1800 1900 2000 Mercator 1512 1594 1897 Rupelmonde Duisburg 1599 tables Lt-gen Wauwermans Italian composite Wright tables article about Mercator in Certain erros in navigation 1752 Biographie belge atlases IATO 1869 middle 15th Century Diderot & d’Alembert “cartes de Mercator” Van Raemdonck Ortelius (1527-1598) Gérard Mercator, sa vie, son oeuvre printing 1570 1600 Theatrum Orbis Thomas Harrriot projection MGRS terrarum 1772 1825 1914 post WWI military grid reference system formulas Johan Lambert Carl Friedrich Gauss Johann Krüger NATO UTM Gerard de Jode (1509-1591) 1645 transverse Mercator transverse Mercator transverse Mercator civil reference system fall of Constantinople Henry Bond 1578 (sphere) (ellipsoid) (ellipsoid) Universal 1492 end of Reconquista Mercatorprojection Transverse Speculum Orbis terrarum formula Gauss-Krüger 1942 grid transverse Mercator developped Mercator Judocus Hondius (1563-1612) + geogr. length John Harrison Plantijn (1520-1589) marine timekeepers use of projection Moretus (1543-1610) magnetic <> geogr north John Dee (1527-1608) useability of projection? 1488 Bartholomeus Dias rounded Cape of Good Hope 1492 Columbus ‘America’ discovered 1498 Vasco da Gama reached India via Africa 1519 – 1522 Magellan around the world Gemma Frisius (1508-1555) 1904 criticism + -- Gaspard van der Heyden (1496-1549) 1974 Arne Peters (Gall-Peters-projection) mariage 5/5/1590 1500 Barbara Shellekens arrested in met Ortelius stroke 1600 CRITICISM - but from non-cartographers - 1536 Rupelmonde in Frankfurt on ethnocentrism, -

Early & Rare World Maps, Atlases & Rare Books

19219a_cover.qxp:Layout 1 5/10/11 12:48 AM Page 1 EARLY & RARE WORLD MAPS, ATLASES & RARE BOOKS Mainly from a Private Collection MARTAYAN LAN CATALOGUE 70 EAST 55TH STREET • NEW YORK, NEW YORK 10022 45 To Order or Inquire: Telephone: 800-423-3741 or 212-308-0018 Fax: 212-308-0074 E-Mail: [email protected] Website: www.martayanlan.com Gallery Hours: Monday through Friday 9:30 to 5:30 Saturday and Evening Hours by Appointment. We welcome any questions you might have regarding items in the catalogue. Please let us know of specific items you are seeking. We are also happy to discuss with you any aspect of map collecting. Robert Augustyn Richard Lan Seyla Martayan James Roy Terms of Sale: All items are sent subject to approval and can be returned for any reason within a week of receipt. All items are original engrav- ings, woodcuts or manuscripts and guaranteed as described. New York State residents add 8.875 % sales tax. Personal checks, Visa, MasterCard, American Express, and wire transfers are accepted. To receive periodic updates of recent acquisitions, please contact us or register on our website. Catalogue 45 Important World Maps, Atlases & Geographic Books Mainly from a Private Collection the heron tower 70 east 55th street new york, new york 10022 Contents Item 1. Isidore of Seville, 1472 p. 4 Item 2. C. Ptolemy, 1478 p. 7 Item 3. Pomponius Mela, 1482 p. 9 Item 4. Mer des hystoires, 1491 p. 11 Item 5. H. Schedel, 1493, Nuremberg Chronicle p. 14 Item 6. Bergomensis, 1502, Supplementum Chronicum p. -

Knowing and Decorating the World Illustrations and Textual Descriptions in the Maps of the Fourth Edition of the Mercator-Hondius Atlas (1613)

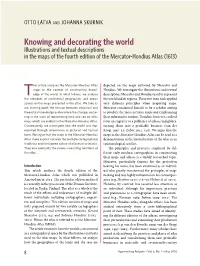

OTTO LATVA AND JOHANNA SKURNIK Knowing and decorating the world Illustrations and textual descriptions in the maps of the fourth edition of the Mercator-Hondius Atlas (1613) his article analyses the Mercator-Hondius Atlas depicted on the maps authored by Mercator and maps in the context of constructing knowl- Hondius. We investigate the illustrations and textual Tedge of the world. In what follows, we analyse descriptions Mercator and Hondius used to represent the elem ents of continental geographies and ocean the world and its regions. These two men each applied spaces on the maps presented in the atlas. We take as very different principles when preparing maps: our starting point the tension between empirical and Mercator considered himself to be a scholar aiming theoretical knowledge and examine the changes occur- to produce the most accurate maps and emphasizing ring in the ways of representing land and sea on atlas their informative content. Hondius, however, evolved maps which are evident in the Mercator-Hondius Atlas. from an engraver to a publisher of atlases and globes, Consequently, we investigate how the world was rep- turning them into a profitable business (van der resented through information in pictorial and textual Krogt 1997: 35; Zuber 2011: 516). We argue that the form. We argue that the maps in the Mercator-Hondius maps in the Mercator-Hondius Atlas can be read as a Atlas make explicit not only the multiple cartographical demonstration of the layered nature of the atlas as an trad itions and the layered nature of atlases as artefacts. epistemological artefact. They also exemplify the various coexisting functions of The principles and practices employed by dif- the atlas. -

From the Old Ages to Mercator

14 The World Image in Maps – From the Old Ages to Mercator Mirjanka Lechthaler Institute of Geoinformation and Cartography Vienna University of Technology, Austria Abstract Studying the Australian aborigines’ ‘dreamtime’ maps or engravings from Dutch cartographers of the 16 th century, one can lose oneself in their beauty. Casually, cartography is a kind of art. Visualization techniques, precision and compliance with reality are of main interest. The centuries of great expeditions led to today’s view and mapping of the world. This chapter gives an overview on the milestones in the history of cartography, from the old ages to Mercator’s map collections. Each map presented is a work of art, which acts as a substitute for its era, allowing us to re-live the circumstances at that time. 14.1 Introduction Long before people were able to write, maps have been used to visualise reality or fantasy. Their content in \ uenced how people saw the world. From studying maps conclusions can be drawn about how visualized regions are experienced, imagined, or meant to be perceived. Often this is in \ uenced by social and political objectives. Cartography is an essential instrument in mapping and therefore preserving cultural heritage. Map contents are expressed by means of graphical language. Only techniques changed – from cuneiform writing to modern digital techniques. From the begin- nings of cartography until now, this language remained similar: clearly perceptible graphics that represented real world objects. The chapter features the brief and concise history of the appearance and develop- ment of topographic representations from Mercator’s time (1512–1594), which was an important period for the development of cartography. -

WILLIAM R. TALBOT FINE ART, ANTIQUE MAPS & PRINTS 505-982-1559 • [email protected] • for Purchases, Please Call Or Email

ILLIAM R TALT FIE ART, ATIE MAPS PRITS 129 West San Francisco Street • P. O. Box 2757, Santa Fe, New Mexico 87504 505-982-1559 • [email protected] • www.williamtalbot.com FALL 2019 Abraham Ortelius’s FIRST EDITION WORLD MAP The present map is a depiction of the world from the Age of Discovery and the earliest edition of Abraham Ortelius’s famous world map rendered in magnificent color. Ortelius was a great compiler of newly discovered geographical facts and information. His New World mapping is also a study in early conjecture, including a generous northwest passage below the Terra Septentrionalis Incognita, and a projection of the St. Lawrence reaching to the middle of the continent. Ortelius’s map includes Terra Australis Nondum Cognita, reflecting the misconception held at the time of a massive southern continent, that incorporates Tierra del Fuego in this southern polar region rather than in South America. The relatively unknown regions across Northeast Asia distort the outline of Japan considerably. In the North Atlantic, the outline of Scandinavia is skewed, and Greenland appears very close to Abraham Ortelius (1528–1598). “Typus Orbis Terrarum,” (Antwerp: 1570). First Edition. Published in the Latin editions of Theatrum Orbis Terrarum. Double- North America. Ortelius published his world maps page copperplate engraving with full hand color and some original color. Signed by in his Theatrum Orbis Terrarum, considered to be engraver l.r. “Franciscus (Frans) Hogenberg”. Latin text, verso: “Orbis Terrarum.” the first modern atlas, with 70 copper engravings and “I”. 13 3/32 x 19 7/16” to neatline. Sheet: 15 9/16 x 20 3/4”. -

Cartographer's Experience of Time in the Mercator-Hondius Atlas (1606

JANNE TUNTURI Cartographer’s experience of time in the Mercator-Hondius Atlas (1606, 1613) his article analyses the articulations of tempor The Mercator-Hondius Atlas is the work of two ality in the MercatorHondius Atlas. Firstly, cartographers who belonged to different generations; Tthe atlas reflects the sense of the past as the Gerardus Mercator (1512–94) was fifty years older cartog raphers had to assess the information included than Jodocus Hondius (1563–1612). Moreover, the in ancient texts in relation to modern testimonies. Sec scale of the atlases differed considerably, as Mercator’s ondly, Hondius had to take into account the worldview edition mapped only European countries (with not- provided by the explorers in the fifteenth and sixteenth able omissions such as Spain), while Hondius’ edi- centuries. Hence the experience of time articulated tion was universal. Mercator drew maps for his atlas in the MercatorHondius Atlas reflected not only the in the 1560s and the 1570s. The unfinished Atlas sive cartog raphers’ ideas of the Dutch cartographic industry cosmo graphicae meditationes de fabrica mundi et fab- but also directed the making of the atlas. ricati figura was published posthumously in 1595. In 1606 Hondius utilised the copperplates on Mercator’s maps he had bought together with Cornelis Claesz. The Mercator-Hondius Atlas, published by and added maps, some of his own, to compile an atlas Jodocus Hondius in 1606, summarises the early-sev- that would be convenient and met current standards. enteenth-century Dutch golden age of map-making, (Van der Krogt 1995: 115–16) famous for the skilled cartographers and the atlases During the publication of Mercator’s and Hondius’ it produced. -

MAPS Maps. Printed and Manuscript. Held in the Royal Society Of

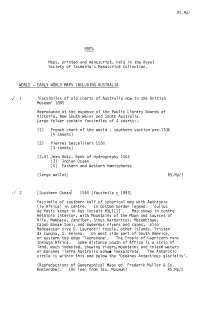

RS.Mpj MAPS Maps. printed and manuscript. held in the Royal Society of Tasmania's Manuscript Collection. WORLD - EARLY WORLD MAPS INCLUDING AUSTRALIA ./ 1 'Facsimiles of old charts of Austral ia now in the British Museum' 1885 Reproduced at the expense of the Public Library Boards of Victoria. New South Wales and South Australia. Large folder contain facsimiles of 4 charts:- (1) French chart of the world - southern section pre-1536 (4 sheets) (2) Pierres Descelliers 1550 (3 sheets) (3.4) Jean Rotz. Book of Hydrography 1542 (3) Indian Ocean (4) Eastern and Western hemispheres (1 arge wallet) RS .Mp/1 '/ 2 LSouthern OceanJ 1554 (facsimile c 1895) Facsimile of southern half of spherical map with Aethiopia (ie Africa) in centre. In bottom border legend: 'Julius de Musis Venet in Aes incidit ~1DLIIII'. Map shows in centre Aethipia Interior. with Mountains of the Moon and sources of Nile. Mombaca. Zanziber. Sinus Barbaricus. Mozambique. Caput Bonae Spei. and numerous rivers and capes; also Madagascar sive D. Laurenti; insula. other islands, Tristan da Cuegna. S. Helena. On west side part of South America. on eastern top edge 'Taprobane'. The Tropic of Capricorn runs through Africa. Some distance south of Africa is a strip of land. much indented, showing rivers. mountains and inland waters or marshes 'Terra Australis adhue inexplorata~ The Antarctic circle is within this and below the 'Oceanus Antacticus glacialis'. (Reproductions of Geographical Maps ed. Frederik Muller & Co. Amsterdam). (On loan from Tas. Museum) RS.Mp/2 - 2 - RS. Mp/ / 45 Mappenmonde - Desliens 1566 (19th Cent. facsimile) Nicholas Desliens of Dieppe. -

Barry Lawrence Ruderman Antique Maps Inc

Barry Lawrence Ruderman Antique Maps Inc. 7407 La Jolla Boulevard www.raremaps.com (858) 551-8500 La Jolla, CA 92037 [email protected] America sive India Nova ad magnae Gerardi Mercatoris avi universalis imitationem incompendium redacta Stock#: 38985 Map Maker: Mercator Date: 1613 circa Place: Amsterdam Color: Hand Colored Condition: VG Size: 18 x 15 inches Price: SOLD Description: Striking Example of Michael Mercator's Map of the Western Hemisphere, the Only Map he Ever Engraved This is a fine example of Mercator's map of the Western Hemisphere, based upon Rumold Mercator's world map of 1587. Fascinatingly, this is the only map that Mercator, Gerard's grandson, engraved. Even so, it shows spectacular skill and artistry. North and South America are shown above a large southern continent. The Pacific stretches to the west, with a large, round New Guinea at the edge of the hemisphere. To the north, three of the four islands Gerard Mercator typically placed around the North Pole are visible. There are four insets in the corners, along with decorative scrollwork that again showcases Michael's engraving prowess. In the upper left is the Gulf of Mexico, the upper right Cuba, the lower left Haiti (nunc Hispaniola), and the lower right a title. Although Gerard Mercator is mentioned in the title, Michael is identified as the engraver and Duisberg as the place where he executed the work. The St. Lawrence River crosses half the northern continent. The search for a water course across North America is interrupted only by some mid-continental mountains. Evidence of the Spanish explorations in the Southwest of North America is present and the Colorado and Gila Rivers already reflect a good knowledge of this area, as does the peninsular Baja California, based upon Ulloa's work. -

The Mercator Projection: Its Uses, Misuses, and Its Association with Scientific Information and the Rise of Scientific Societies

ABEE, MICHELE D., Ph.D. The Mercator Projection: Its Uses, Misuses, and Its Association with Scientific Information and the Rise of Scientific Societies. (2019) Directed by Dr. Jeff Patton and Dr. Linda Rupert. 309 pp. This study examines the uses and misuses of the Mercator Projection for the past 400 years. In 1569, Dutch cartographer Gerard Mercator published a projection that revolutionized maritime navigation. The Mercator Projection is a rectangular projection with great areal exaggeration, particularly of areas beyond 50 degrees north or south, and is ill-suited for displaying most reference and thematic world maps. The current literature notes the significance of Gerard Mercator, the Mercator Projection, the general failings of the projection, and the twentieth century controversies that arose as a consequence of its misuse. This dissertation illustrates the path of the institutionalization of the Mercator Projection in western cartography and the roles played by navigators, scientific societies and agencies, and by the producers of popular reference and thematic maps and atlases. The data are pulled from the publication record of world maps and world maps in atlases for content analysis. The maps ranged in date from 1569 to 1900 and displayed global or near global coverage. The results revealed that the misuses of the Mercator Projection began after 1700, when it was connected to scientists working with navigators and the creation of thematic cartography. During the eighteenth century, the Mercator Projection was published in journals and reports for geographic societies that detailed state-sponsored explorations. In the nineteenth century, the influence of well- known scientists using the Mercator Projection filtered into the publications for the general public. -

Gerardus Mercator (5 De Marzo, 1512 -2 De Diciembre, 1594) Fue Un Cartógrafo Belga, Recordado Por Su Proyección De Mercator

Manual Técnico ECO Sistema de Coordenadas Universal Transversal de Mercator UTM Gerardo Mercator o Gerardus Mercator (5 de marzo, 1512 -2 de diciembre, 1594) fue un cartógrafo belga, recordado por su proyección de Mercator. Nació con el nombre Gerard de Cremere (o Kremer) en Rupelmonde, Flandes. "Mercator" es la latinización de su nombre, que significa "mercader". Recibió su educación formal del humanista Macro- pedius en Bolduque y en la Universidad de Leuven. Aunque nunca viajó mucho, desarrolló siendo joven un interés en la geografía como un medio de ganarse la vida. Mientras vivió en Leuven trabajó junto a Gemma Frisius y Gaspar Myrica entre 1535 y 1536 en la construcción de un globo terráqueo. Posterior- mente, Mercator publicó un mapa de Palestina (en 1537), un planisferio (en 1538) y un mapa de Flandes en 1540. A lo largo de estos años, aprendió a escribir en itálica, un tipo de letra más adecuado para los grabados en cobre de los mapas. Escribió al respecto un libro que fue el primero que trataba sobre este tema Europa del Norte. En 1544 es acusado de hereje y pasa en prisión siete meses. En 1552 , se traslada a Duisburgo donde abre un taller de cartografía. Trabajó en la realización de un mapa, compuesto por seis paneles, de Europa que completó en 1554, y también se dedicó a enseñar matemática. Realizó algunos otros ma- pas y, finalmente, fue nombrado cosmógrafo de la corte por el duque Wilhelm de Cléveris, en 1564. Du- rante estos años, concibió la idea de una nueva proyección para su uso en los mapas, que usó por prime- ra vez en 1569; lo novedoso era que las líneas de longitud eran paralelas, lo cual facilitaba la navegación por mar al poderse marcar las direcciones de las brújulas en líneas rectas. -

Netherlandic Treasures

Deep Blue Deep Blue https://deepblue.lib.umich.edu/documents Research Collections Library (University of Michigan Library) 2014 Netherlandic Treasures Vandersypen, Karla https://hdl.handle.net/2027.42/120264 Downloaded from Deep Blue, University of Michigan's institutional repository Netherlandic Treasures 6 June – 28 August 2014 Special Collections Exhibit Space 7th Floor, Hatcher South University of Michigan Ann Arbor, Michigan © 2014 University of Michigan Library (Special Collections Library) All rights reserved. Guest curator Karla Vandersypen gratefully thanks Pablo Alvarez, Martha Conway, Karl Longstreth, and Tim Utter; Cathleen Baker, Thomas Hogarth, Brooke Adams, Erin Kraus, and Melissa Gomis. Please visit the online exhibit at: http://www.lib.umich.edu/netherlandic-treasures/welcome.html Netherlandic Treasures This exhibition is a selection of some of the most notable Dutch and Flemish printed books, manuscripts, and maps held by the University of Michigan Library: the earliest, most beautiful, rarest, or the most unusual. A special point has been made to tell how and why these materials have been acquired over the years. One could reduce the “why” to two principal reasons: the efforts of past librarians and administrators to create a research collection in the Midwest of the United States, and the presence of a significant group of inhabitants of Dutch heritage in the western part of the state of Michigan. Information as to the “how” is part of the explanatory label for most items shown: when and from whom purchased or received as a gift. The earliest item is also one of the most beautiful: an illuminated Book of Hours, written and painted on vellum in The Netherlands during the second quarter of the fifteenth century. -

Vladi Collection Sep

Legendary Vladi Collection of Historical Maps 1: Aa, Pieter van der. World and continents (set) USD 24,000 - 30,000 Aa, Pieter van derSet of Five Maps (AA, Pieter Van Der)1713Copperplate engraving; Later colourPrinted area: America: 65.7 x 47.2 cm; 25.9 x 18.6 inEurope: 65.3 x 47 cm; 25.7 x 18.5 inAfrica: 65 x 47.5 cm; 25.6 x 18.7 inAsia: 65.2 x 47 cm; 25.7 x 18.5 inWorld: 62.5 x 49.5 cm; 24.6 x 19.5 inA set of four large maps of the continents - each with a fine, full-colour title cartouche - first published in Van der Aa's atlas, 'Le Nou- veau theatre du monde.' In contrast to other contemporary maps of the world, the double hemisphere map dispenses with the delineation of depictions of a huge sub-continent in the Antarctic and gigantic expansions of North America and Australia. With the exception of a few speculative coastlines, unknown regions are left blank, resulting in the northwestern extension of North America being left blank. By the 16th Century, it was largely common knowledge that California was a peninsula. Yet despite evidence to the contrary, this cartographic error went on to be reproduced many time. Whilst the western and northern coastlines of Australia are visible, the continent is still shown as being connected to New Guinea. The title (towards the bottom-middle) is written in French and states that the map is based on the latest results from the 'Academie des Sciences' - an institution founded by Louis XIV in 1666.