Cosmographer Networks of Sebastian Münster, Gerard Mercator, and Abraham Ortelius (1540-1570)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Catalogue Summer 2012

JONATHAN POTTER ANTIQUE MAPS CATALOGUE SUMMER 2012 INTRODUCTION 2012 was always going to be an exciting year in London and Britain with the long- anticipated Queen’s Jubilee celebrations and the holding of the Olympic Games. To add to this, Jonathan Potter Ltd has moved to new gallery premises in Marylebone, one of the most pleasant parts of central London. After nearly 35 years in Mayfair, the move north of Oxford Street seemed a huge step to take, but is only a few minutes’ walk from Bond Street. 52a George Street is set in an attractive area of good hotels and restaurants, fine Georgian residential properties and interesting retail outlets. Come and visit us. Our summer catalogue features a fascinating mixture of over 100 interesting, rare and decorative maps covering a period of almost five hundred years. From the fifteenth century incunable woodcut map of the ancient world from Schedels’ ‘Chronicarum...’ to decorative 1960s maps of the French wine regions, the range of maps available to collectors and enthusiasts whether for study or just decoration is apparent. Although the majority of maps fall within the ‘traditional’ definition of antique, we have included a number of twentieth and late ninteenth century publications – a significant period in history and cartography which we find fascinating and in which we are seeing a growing level of interest and appreciation. AN ILLUSTRATED SELECTION OF ANTIQUE MAPS, ATLASES, CHARTS AND PLANS AVAILABLE FROM We hope you find the catalogue interesting and please, if you don’t find what you are looking for, ask us - we have many, many more maps in stock, on our website and in the JONATHAN POTTER LIMITED gallery. -

Barry Lawrence Ruderman Antique Maps Inc

Barry Lawrence Ruderman Antique Maps Inc. 7407 La Jolla Boulevard www.raremaps.com (858) 551-8500 La Jolla, CA 92037 [email protected] Typus Cosmographicus Universalis Tiguri Anno M.D. XXXIIII Stock#: 51052 Map Maker: Vadianus Date: 1534 Place: Zurich Color: Uncolored Condition: VG+ Size: 15.5 x 11.5 inches Price: SOLD Description: Fine Example of One of Earliest Obtainable Maps to Use "America" and Show a Western Ocean Fine example of the first state of Vadianus' scarce oval projection published by Zurich's first printer, Christopher Frosch. This is one of the earliest obtainable maps to show an ocean to the west of the American continent, which is not yet named. It is also one of the earliest obtainable maps to use the name America, the first being the Waldseemuller map in 1507 (one known example) and the second (and earliest obtainable) being the Peter Apian map of 1520. The map shows North America as a narrow unrecognizable sliver, while South America is recognizable. The Old World appears much as we know it, except for the "tail" that seems to connect the East Indies to the continent of Asia. This "tail" is a remnant of the Ptolemaic world map that depicted the Indian Ocean as an inland sea surrounded by land. Here, there are no lands to the south, although Scandinavia extends right to the North Pole. The map shows a passage between the Americas and Terra de Cuba in North America rather than an isthmus. The toponyms used on the map are an eclectic mix of Ptolemaic and modern geographical place names. -

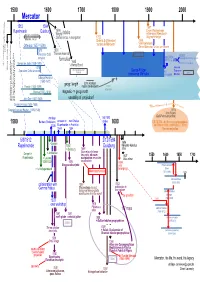

Visio-MERCATOR ENG2.Vsd

1500 1600 1700 1800 1900 2000 Mercator 1512 1594 1897 Rupelmonde Duisburg 1599 tables Lt-gen Wauwermans Italian composite Wright tables article about Mercator in Certain erros in navigation 1752 Biographie belge atlases IATO 1869 middle 15th Century Diderot & d’Alembert “cartes de Mercator” Van Raemdonck Ortelius (1527-1598) Gérard Mercator, sa vie, son oeuvre printing 1570 1600 Theatrum Orbis Thomas Harrriot projection MGRS terrarum 1772 1825 1914 post WWI military grid reference system formulas Johan Lambert Carl Friedrich Gauss Johann Krüger NATO UTM Gerard de Jode (1509-1591) 1645 transverse Mercator transverse Mercator transverse Mercator civil reference system fall of Constantinople Henry Bond 1578 (sphere) (ellipsoid) (ellipsoid) Universal 1492 end of Reconquista Mercatorprojection Transverse Speculum Orbis terrarum formula Gauss-Krüger 1942 grid transverse Mercator developped Mercator Judocus Hondius (1563-1612) + geogr. length John Harrison Plantijn (1520-1589) marine timekeepers use of projection Moretus (1543-1610) magnetic <> geogr north John Dee (1527-1608) useability of projection? 1488 Bartholomeus Dias rounded Cape of Good Hope 1492 Columbus ‘America’ discovered 1498 Vasco da Gama reached India via Africa 1519 – 1522 Magellan around the world Gemma Frisius (1508-1555) 1904 criticism + -- Gaspard van der Heyden (1496-1549) 1974 Arne Peters (Gall-Peters-projection) mariage 5/5/1590 1500 Barbara Shellekens arrested in met Ortelius stroke 1600 CRITICISM - but from non-cartographers - 1536 Rupelmonde in Frankfurt on ethnocentrism, -

Arias Montano, Mediador Entre España Y Flandes, Por Vicente Bécares Botas, Universidad De Salamanca 273 Carta De Arias Montano a Fray Luis De León

DIRECTORA LYDIA JIMÉNEZ SECRETARIO RAMIRO FLÓREZ CONSEJO EDITORIAL JOSÉT.RAGA RAÚL VÁZQUEZ CONSOLACIÓN MORALES AMANCIO LABANDEIRA JOSÉ LUIS CAÑAS ANDRÉS JIMÉNEZ JAVIER RUIZ SERRADILLA SECRETARÍA: Alcalá, 93. 28009 Madrid. Teléfono 91 431 11 93 ISSN: 0214-0284 Depósito Legal: M-37.362-1987 Cuadernos de Pensamiento 12 PUBLICACIÓN DEL SEMINARIO «ÁNGEL GONZÁLEZ ÁLVAREZ» DE LA FUNDACIÓN UNIVERSITARIA ESPAÑOLA SUMARIO ESPECIAL DEDICADO A B. ARIAS MONTANO Presentación, por Lydia Jiménez 7 I. CONFERENCIAS Palabras de Presentación del Ciclo, por el Excmo. Sr. D. Antonio Garrigues Díaz- Cañabate 11 La Universidad de Alcalá y la formación humanista, bíblica y arqueológica de Benito Arias Montano, por Antonio Martínez Ripoll, Universidad de Alca- lá 13 Filología bíblica y humanismo, por Natalio Femández Marcos, CSIC 93 Actitud ante la Filosofía y Humanismo cultural de Arias Montano, por Ramiro Flórez, Fundación Universitaria Española 111 Transmisión histórica y valoración actual del biblismo de Arias Montano, por Gaspar Morocho, Universidad de León 135 n. COLABORACIONES Los presupuestos de la Hermenéutica de M. Heidegger, por José Luis Canee- lo............................................................................................................... 243 Arias Montano, mediador entre España y Flandes, por Vicente Bécares Botas, Universidad de Salamanca 273 Carta de Arias Montano a Fray Luis de León. Comentario, edición y traduccián, por Juan Francisco Domínguez Domínguez, Universidad de León 285 Traducción de un poema de Arias Montano sobre un cuadro de Zúcaro, por María Violeta Pérez Custodio, Universidad de Cádiz 313 El Prólogo del Opus Magnum de Benito Arias Montano, por J. José de Jorge López, Universidad Complutense 317 Crónica y resumen del XI Curso de Pedagogía para Educadores, por Teresa Cid 351 COLABORADORES DE ESTE NÚMERO (orden alfabético): BÉCARES BOTAS, Vicente CANCELO, José LUIS CID, Teresa DE JORGE LÓPEZ, J. -

![List 3-2016 Accademia Della Crusca – Aldine Device 1) [BARDI, Giovanni (1534-1612)]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5354/list-3-2016-accademia-della-crusca-aldine-device-1-bardi-giovanni-1534-1612-465354.webp)

List 3-2016 Accademia Della Crusca – Aldine Device 1) [BARDI, Giovanni (1534-1612)]

LIST 3-2016 ACCADEMIA DELLA CRUSCA – ALDINE DEVICE 1) [BARDI, Giovanni (1534-1612)]. Ristretto delle grandeze di Roma al tempo della Repub. e de gl’Imperadori. Tratto con breve e distinto modo dal Lipsio e altri autori antichi. Dell’Incruscato Academico della Crusca. Trattato utile e dilettevole a tutti li studiosi delle cose antiche de’ Romani. Posto in luce per Gio. Agnolo Ruffinelli. Roma, Bartolomeo Bonfadino [for Giovanni Angelo Ruffinelli], 1600. 8vo (155x98 mm); later cardboards; (16), 124, (2) pp. Lacking the last blank leaf. On the front pastedown and flyleaf engraved bookplates of Francesco Ricciardi de Vernaccia, Baron Landau, and G. Lizzani. On the title-page stamp of the Galletti Library, manuscript ownership’s in- scription (“Fran.co Casti”) at the bottom and manuscript initials “CR” on top. Ruffinelli’s device on the title-page. Some foxing and browning, but a good copy. FIRST AND ONLY EDITION of this guide of ancient Rome, mainly based on Iustus Lispius. The book was edited by Giovanni Angelo Ruffinelli and by him dedicated to Agostino Pallavicino. Ruff- inelli, who commissioned his editions to the main Roman typographers of the time, used as device the Aldine anchor and dolphin without the motto (cf. Il libro italiano del Cinquec- ento: produzione e commercio. Catalogo della mostra Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale, Roma 20 ottobre - 16 dicembre 1989, Rome, 1989, p. 119). Giovanni Maria Bardi, Count of Vernio, here dis- guised under the name of ‘Incruscato’, as he was called in the Accademia della Crusca, was born into a noble and rich family. He undertook the military career, participating to the war of Siena (1553-54), the defense of Malta against the Turks (1565) and the expedition against the Turks in Hun- gary (1594). -

Download Full Article in PDF Format

Serpents buveurs d’eau, serpents œnophiles et serpents sanguinaires : les serpents et leurs boissons dans les sources antiques Jean TRINQUIER* ENS Ulm, AOROC-UMR 8546 CNRS-ENS. [email protected] Trinquier J. 2012. Serpents buveurs d’eau, serpents œnophiles et serpents sanguinaires : les serpents et leurs boissons dans les sources antiques. Anthropozoologica 47.1 : 177-221. Les serpents ont-ils soif ? Que boivent-ils ? À ces deux questions, les sources antiques ap- portent des réponses contrastées, qui tantôt valent pour tous les ophidiens, tantôt seule- ment pour certaines espèces. D’un côté, les serpents passaient pour des animaux froids, et on concluait logiquement qu’ils n’avaient pas besoin de beaucoup boire, une déduction confirmée par l’observation de spécimens captifs ; telle était notamment la position d’Aris- tote. D’un autre côté, les serpents venimeux, en particulier les Vipéridés, étaient volontiers MOTS CLÉS mis en rapport avec le chaud et le sec, en raison tant de leur virulence estivale que des effets physiologie composition assoiffants de leur venin ; ils étaient plus facilement que d’autres décrits comme assoiffés, crase ou amateurs de vin, le vin étant lui aussi considéré comme chaud et sec. Un autre serpent toxicologie assoiffé est le python des confins indiens et éthiopiens, censé attaquer les éléphants pour épistémologie légendes les vider de leur sang à la façon d’une sangsue. À travers ces différents cas, la contribution vin étudie la façon dont s’est élaborée dans l’Antiquité, à partir d’un stock disparate de données sang serpents géants légendaires, de représentations mythiques et d’observations attentives, une réflexion sur la vampire crase des différentes espèces d’ophidiens. -

Las Dos Versiones De La De Psalterii Anglicani Exemplari Animaduersio De Benito Arias Montano En La Biblia Políglota De Amberes*

SEFARAD, vol. 74:1, enero-junio 2014, págs. 185-254 ISSN: 0037-0894, doi:10.3989/sefarad.014.006 Las dos versiones de la De Psalterii Anglicani exemplari animaduersio de Benito Arias Montano en la Biblia Políglota de Amberes* Antonio Dávila Pérez** Universidad de Cádiz En el octavo y último volumen de la Biblia Regia de Amberes Benito Arias Montano publicaba un breve texto titulado De Psalterii Anglicani exemplari animaduersio. En el marco de su defensa del original hebreo del Antiguo Testamento, su autor consideraba necesario advertir al lector de que algunos de los manuscritos más apreciados por los llamados «misohebreos» de su tiempo carecían de todo valor. Para ello, Arias Montano examinó un manuscrito hebreo del salterio elogiado como muy antiguo y relevante por el poderoso obispo Guillermo D. Lindano, y concluía que el códice era reciente y de escaso valor, cargando de paso contra la reputación científica de este. El ataque, fundamentado en parte en una falsa denuncia, sería el punto de partida de una controversia personal y científica que se extiende durate más de quince años. El presente artículo llama la atención sobre el hecho de que en los ejemplares conservados de la Políglota se pueden leer dos versiones de la Animaduersio montaniana muy diferentes entre sí. Con objeto de aclarar las circunstancias y motivos que las originaron, el autor propone: (1) reunir en un único estudio, por vez primera, el texto latino y la traducción al español de las dos versiones de la Animaduersio; (2) investigar, a la luz de la correspondencia privada de Arias Montano y de Lindano, las razones que propiciaron la existencia de dos versiones tan distintas de este prefacio; (3) y conjeturar una datación aproximada para cada una de las versiones. -

California Virtual Book Fair 2021

Bernard Quaritch Ltd 50 items for the 2021 Virtual California Book Fair BERNARD QUARITCH LTD 36 Bedford Row, London, WC1R 4JH tel.: +44 (0)20 7297 4888 fax: +44 (0)20 7297 4866 email: [email protected] web: www.quaritch.com Front cover image from item 20. LALIEU, Paul and Nicolas Joseph BEAUTOUR. P[hiloso]phia particularis Inside cover background from item 8. [CANONS REGULAR OF THE LATERAN]. Regula et constitutiones Canonicorum Regularium Last page images from item 13. [CUSTOMARY LAW]. Rechten, ende costumen van Antwerpen. and item 29. MARKHAM, Cavalarice, or the English Horseman Bankers: Barclays Bank PLC 1 Churchill Place London E14 5HP Sort code: 20-65-90 Account number: 10511722 Swift code: BUKBGB22 Sterling account: IBAN: GB71 BUKB 2065 9010 5117 22 Euro account: IBAN: GB03 BUKB 2065 9045 4470 11 U.S. Dollar account: IBAN: GB19 BUKB 2065 9063 9924 44 VAT number: GB 322 4543 31 ALDROVANDI'S QUADRUPEDS IN FIRST EDITION 1. ALDROVANDI, Ulisse. De quadrupedibus solidipedibus volume integrum … cum indice copiosissimo. Bologna, Vittoria Benacci for Girolamo Tamburini, 1616. [with:] Quadrupedum omnium bisulcorum historia … ucm indice copiosissimo. Bologna, Sebastiano Bonomi for Girolamo Tamburini, 1621. [and:] De quadrupedibus digitatis viviparis libri tres, et de quadrupedibus digitatis oviparis libri duo … cum indice memorabiliumetvariarumlinguarumcopiosissimo. Bologna,NicolaoTebaldiniforMarcoAntonioBernia,1637. 3 vols, folio, pp. 1: [8], 495, [1 (blank)], [30], [2 (colophon, blank)], 2: [11], [1 (blank)], 1040, [12], 3: [8], 492, ‘495-718’ [i.e. 716], [16];eachtitlecopper-engravedbyGiovanniBattistaCoriolano,withwoodcutdevicestocolophons,over200largewoodcutillustrations (12, 77, and 130 respectively), woodcut initials and ornaments; a few leaves lightly foxed and occasional minor stains, a little worming to early leaves vol. -

Early & Rare World Maps, Atlases & Rare Books

19219a_cover.qxp:Layout 1 5/10/11 12:48 AM Page 1 EARLY & RARE WORLD MAPS, ATLASES & RARE BOOKS Mainly from a Private Collection MARTAYAN LAN CATALOGUE 70 EAST 55TH STREET • NEW YORK, NEW YORK 10022 45 To Order or Inquire: Telephone: 800-423-3741 or 212-308-0018 Fax: 212-308-0074 E-Mail: [email protected] Website: www.martayanlan.com Gallery Hours: Monday through Friday 9:30 to 5:30 Saturday and Evening Hours by Appointment. We welcome any questions you might have regarding items in the catalogue. Please let us know of specific items you are seeking. We are also happy to discuss with you any aspect of map collecting. Robert Augustyn Richard Lan Seyla Martayan James Roy Terms of Sale: All items are sent subject to approval and can be returned for any reason within a week of receipt. All items are original engrav- ings, woodcuts or manuscripts and guaranteed as described. New York State residents add 8.875 % sales tax. Personal checks, Visa, MasterCard, American Express, and wire transfers are accepted. To receive periodic updates of recent acquisitions, please contact us or register on our website. Catalogue 45 Important World Maps, Atlases & Geographic Books Mainly from a Private Collection the heron tower 70 east 55th street new york, new york 10022 Contents Item 1. Isidore of Seville, 1472 p. 4 Item 2. C. Ptolemy, 1478 p. 7 Item 3. Pomponius Mela, 1482 p. 9 Item 4. Mer des hystoires, 1491 p. 11 Item 5. H. Schedel, 1493, Nuremberg Chronicle p. 14 Item 6. Bergomensis, 1502, Supplementum Chronicum p. -

Bulletin De La Sabix, 39 | 2005 Géodésie, Topographie Et Cartographie 2

Bulletin de la Sabix Société des amis de la Bibliothèque et de l'Histoire de l'École polytechnique 39 | 2005 André-Louis Cholesky (1875-1918) Géodésie, topographie et cartographie C. Brezinski Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/sabix/525 DOI : 10.4000/sabix.525 ISSN : 2114-2130 Éditeur Société des amis de la bibliothèque et de l’histoire de l’École polytechnique (SABIX) Édition imprimée Date de publication : 1 décembre 2005 Pagination : 32 - 66 ISBN : ISSN N° 2114-2130 ISSN : 0989-30-59 Référence électronique C. Brezinski, « Géodésie, topographie et cartographie », Bulletin de la Sabix [En ligne], 39 | 2005, mis en ligne le 07 décembre 2010, consulté le 21 décembre 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/ sabix/525 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/sabix.525 Ce document a été généré automatiquement le 21 décembre 2020. © SABIX Géodésie, topographie et cartographie 1 Géodésie, topographie et cartographie C. Brezinski 1 La géodésie s’occupe de la détermination mathématique de la forme de la Terre. Les observations géodésiques conduisent à des données numériques : forme et dimensions de la Terre, coordonnées géographiques des points, altitudes, déviations de la verticale, longueurs d’arcs de méridiens et de parallèles, etc. 2 La topographie est la sœur de la géodésie. Elle s’intéresse aux mêmes quantités, mais à une plus petite échelle, et elle rentre dans des détails de plus en plus fins pour établir des cartes à différentes échelles et suivre pas à pas les courbes de niveau. La topométrie constitue la partie mathématique de la topographie. 3 La cartographie proprement dite est l’art d’élaborer, de dessiner les cartes, avec souvent un souci artistique. -

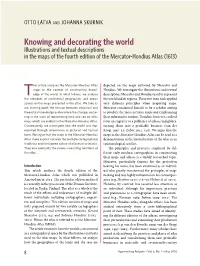

Knowing and Decorating the World Illustrations and Textual Descriptions in the Maps of the Fourth Edition of the Mercator-Hondius Atlas (1613)

OTTO LATVA AND JOHANNA SKURNIK Knowing and decorating the world Illustrations and textual descriptions in the maps of the fourth edition of the Mercator-Hondius Atlas (1613) his article analyses the Mercator-Hondius Atlas depicted on the maps authored by Mercator and maps in the context of constructing knowl- Hondius. We investigate the illustrations and textual Tedge of the world. In what follows, we analyse descriptions Mercator and Hondius used to represent the elem ents of continental geographies and ocean the world and its regions. These two men each applied spaces on the maps presented in the atlas. We take as very different principles when preparing maps: our starting point the tension between empirical and Mercator considered himself to be a scholar aiming theoretical knowledge and examine the changes occur- to produce the most accurate maps and emphasizing ring in the ways of representing land and sea on atlas their informative content. Hondius, however, evolved maps which are evident in the Mercator-Hondius Atlas. from an engraver to a publisher of atlases and globes, Consequently, we investigate how the world was rep- turning them into a profitable business (van der resented through information in pictorial and textual Krogt 1997: 35; Zuber 2011: 516). We argue that the form. We argue that the maps in the Mercator-Hondius maps in the Mercator-Hondius Atlas can be read as a Atlas make explicit not only the multiple cartographical demonstration of the layered nature of the atlas as an trad itions and the layered nature of atlases as artefacts. epistemological artefact. They also exemplify the various coexisting functions of The principles and practices employed by dif- the atlas. -

Biblioteca.Txt 50 De Ani De La Apariția Operei Lui V.I

Biblioteca.txt 50 De Ani De La Apariția Operei Lui V.I. Lenin „Materialism Și Empiriocriticism”. Edited by C.I Gulian. București: Academiei RPR, 1960. 150 De Ani De Lectură Publică. Biblioteca... Edited by Silviu Borș. Sibiu: Armanis, 2011. 1948: Marea Dramă a României. Edited by Ioan Păuc Otiman. București: Academia Română, 2013. Abbrüche Und Aufbrüche. Die Rumäniendeutschen ... Sibiu: Honterus, 2014. Academia Artelor Tradiționale Din România. Edited by Corneliu Bucur. Sibiu: Astra Museum, 2008. Academia Română 1866-2016. Edited by Ionel-Valentin Vlad. București: Academia Română, 2016. Academia Română Și Casa Regală a României. București: Academia Română, 2013. Academia Română. Filiala Cluj-Napoca. Cercetarea ... Cluj-Napoca: Mega, 2016. Activitatea Științifică a Institutului De Istorie „G. Barițiu”. Edited by Nicolae Edroiu. București: Enciclopedică, 2011. Acțiunea „Recuperarea”. Securitatea Și Emigrarea ... București: Ed. Enciclopedică, 2011. Alltag Und Materielle Kultur Im Mittelalaterichen Ungarn. Edited by András Kubiny. Krems: Gesellschaft zur Erforschung der materiellen Kultur des Mittelalters, 1991. Am Kreuzweg Der Geschichte: Mühlbach Im Unterwald. Siebenbürgen. Edited by Gerhard M. Wagner. Moosburg a.d. Isar: HOG Mühlbach, 2014. The Ambiguous Nation Case Studies From... München: Oldenbourg, 2013. Amintirile Colonelului Lăcusteanu ... București: Polirom, 2015. Analele Academiei Rsr. Seria a Iv-A. București, 1982. Ancient Linear Fortifications on the Lower Danube ... Edited by Valeriu Sîrbu. Cluj-Napoca: Mega, 2015. Anfänge Des Städtewesens an Schelde, Maas Und Rhein Bis Zum Jahre 1000. Edited by Adriaan Verhulst. Köln, Wien: Böhlau, 1996. Antidoron. Centenarul Acad. Emil Condurachi (1912-2012). Edited Page 1 Biblioteca.txt by Zoe Petre. București: Academia Română, 2012. Antologie De Filosofie Românească. Edited by Mircea Mâciu. 3 vols.