Early & Rare World Maps, Atlases & Rare Books

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TITLE: Pomponius Mela's World Map DATE: A.D. 37 AUTHOR: Pomponius Mela

Pomponius Mela’s World View #116 TITLE: Pomponius Mela’s World Map DATE: A.D. 37 AUTHOR: Pomponius Mela DESCRIPTION: The images in this monograph show attempts at reconstruction of the world view of the earliest Roman geographer Pomponius Mela, who, although of Spanish birth, wrote a brief work which agrees in most of its views with the great Greek writers from Eratosthenes (#112) to Strabo (#115). However, Mela departs from the traditional ancient concept by asserting that in the southern temperate zone dwelt inhabitants who were inaccessible to Europeans because of the Torrid Zone that intervened. His knowledge of the characters of Western Europe and the British Isles was clearer than that of the Greek writers, and he was the first to name the Orcades [Orkney Islands]. The great Roman historian Pliny quoted Mela as an authority. The first-century author Pomponius Mela enjoyed a long- standing reputation in geographical matters, given Pliny’s praise of him in the Natural History. But no text by Mela was known until the 1330s, when Petrarch discovered his De chorographia [On Chorography, or Descriptive Geography] in Avignon. Mela did not include a map in his text, but it has been suggested that he had in mind the map of the known world that Agrippa (#118) had started and Augustus completed. Displayed in the Porticus Vipsania in Rome, this map was known as chorographia, a name possibly recalled by the title of Mela’s text. Petrarch was fascinated with Mela’s brief and engaging text and had copies made for fellow humanists, including Giovanni Boccaccio, facilitating the wide circulation of the manuscript for almost a century, until it was printed in Milan in 1471. -

Catalogue Summer 2012

JONATHAN POTTER ANTIQUE MAPS CATALOGUE SUMMER 2012 INTRODUCTION 2012 was always going to be an exciting year in London and Britain with the long- anticipated Queen’s Jubilee celebrations and the holding of the Olympic Games. To add to this, Jonathan Potter Ltd has moved to new gallery premises in Marylebone, one of the most pleasant parts of central London. After nearly 35 years in Mayfair, the move north of Oxford Street seemed a huge step to take, but is only a few minutes’ walk from Bond Street. 52a George Street is set in an attractive area of good hotels and restaurants, fine Georgian residential properties and interesting retail outlets. Come and visit us. Our summer catalogue features a fascinating mixture of over 100 interesting, rare and decorative maps covering a period of almost five hundred years. From the fifteenth century incunable woodcut map of the ancient world from Schedels’ ‘Chronicarum...’ to decorative 1960s maps of the French wine regions, the range of maps available to collectors and enthusiasts whether for study or just decoration is apparent. Although the majority of maps fall within the ‘traditional’ definition of antique, we have included a number of twentieth and late ninteenth century publications – a significant period in history and cartography which we find fascinating and in which we are seeing a growing level of interest and appreciation. AN ILLUSTRATED SELECTION OF ANTIQUE MAPS, ATLASES, CHARTS AND PLANS AVAILABLE FROM We hope you find the catalogue interesting and please, if you don’t find what you are looking for, ask us - we have many, many more maps in stock, on our website and in the JONATHAN POTTER LIMITED gallery. -

Geographic Board Games

GSR_3 Geospatial Science Research 3. School of Mathematical and Geospatial Science, RMIT University December 2014 Geographic Board Games Brian Quinn and William Cartwright School of Mathematical and Geospatial Sciences RMIT University, Australia Email: [email protected] Abstract Geographic Board Games feature maps. As board games developed during the Early Modern Period, 1450 to 1750/1850, the maps that were utilised reflected the contemporary knowledge of the Earth and the cartography and surveying technologies at their time of manufacture and sale. As ephemera of family life, many board games have not survived, but those that do reveal an entertaining way of learning about the geography, exploration and politics of the world. This paper provides an introduction to four Early Modern Period geographical board games and analyses how changes through time reflect the ebb and flow of national and imperial ambitions. The portrayal of Australia in three of the games is examined. Keywords: maps, board games, Early Modern Period, Australia Introduction In this selection of geographic board games, maps are paramount. The games themselves tend to feature a throw of the dice and moves on a set path. Obstacles and hazards often affect how quickly a player gets to the finish and in a competitive situation whether one wins, or not. The board games examined in this paper were made and played in the Early Modern Period which according to Stearns (2012) dates from 1450 to 1750/18501. In this period printing gradually improved and books and journals became more available, at least to the well-off. Science developed using experimental techniques and real world observation; relying less on classical authority. -

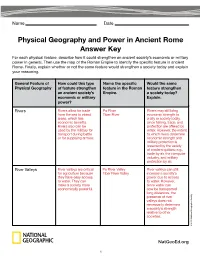

Physical Geography and Power in Ancient Rome Answer

Name Date Physical Geography and Power in Ancient Rome Answer Key For each physical feature, describe how it could strengthen an ancient society’s economic or military power in general. Then use the map of the Roman Empire to identify the specific feature in ancient Rome. Finally, explain whether or not the same feature would strengthen a society today and explain your reasoning. General Feature of How could this type Name the specific Would the same Physical Geography of feature strengthen feature in the Roman feature strengthen an ancient society’s Empire. a society today? economic or military Explain. power? Rivers Rivers allow for trade Po River Rivers may still bring from the sea to inland Tiber River economic strength to areas, which has a city or society today, economic benefits. since fishing, trade, and Rivers also can be protection are offered by used by the military for water. However, the extent transport during battle to which rivers determine or for supplying armies. economic strength and military protection is lessened by the variety of modern options: e.g., trade by air, the computer industry, and military protection by air. River Valleys River valleys are critical Po River Valley River valleys can still for agriculture because Tiber River Valley increase a society’s they have easy access power due to access to water. They can to water. However, make a society more since water can economically powerful. now be transported long distances, the presence of river valleys does not necessarily determine a society’s strength relative to other societies. © 2015 National Geographic Society NatGeoEd.org 1 Physical Geography and Power in Ancient Rome Answer Key, continued General Feature of How could this type Name the specific Would the same Physical Geography of feature strengthen feature in the Roman feature strengthen an ancient society’s Empire. -

A Utumn Catalogue 2016

Autumn Catalogue 2016 antiquariaat FORUM & ASHER Rare Books Autumn Catalogue 2016 ’t Goy-Houten 2016 autumn catalogue 2016 Extensive descriptions and images available on request. All offers are without engagement and subject to prior sale. All items in this list are complete and in good condition unless stated otherwise. Any item not agreeing with the description may be returned within one week after receipt. Prices are EURO (€). Postage and insurance are not included. VAT is charged at the standard rate to all EU customers. EU customers: please quote your VAT number when placing orders. Preferred mode of payment: in advance, wire transfer or bankcheck. Arrangements can be made for MasterCard and VisaCard. Ownership of goods does not pass to the purchaser until the price has been paid in full. General conditions of sale are those laid down in the ILAB Code of Usages and Customs, which can be viewed at: <www.ilab.org/eng/ilab/code.html>. New customers are requested to provide references when ordering. Orders can be sent to either firm. Tuurdijk 16 Tuurdijk 16 3997 ms ‘t Goy – Houten 3997 ms ‘t Goy – Houten The Netherlands The Netherlands Phone: +31 (0)30 6011955 Phone: +31 (0)30 6011955 Fax: +31 (0)30 6011813 Fax: +31 (0)30 6011813 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.forumrarebooks.com Web: www.asherbooks.com front cover: no. 163 on p. 90. v 1.1 · 12 Dec 2016 p. 136: no. 230 on p. 123. inside front cover: no. 32 on p. 23. inside back cover: no. -

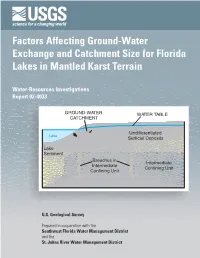

Factors Affecting Ground-Water Exchange and Catchment Size for Florida Lakes in Mantled Karst Terrain

Factors Affecting Ground-Water Exchange and Catchment Size for Florida Lakes in Mantled Karst Terrain Water-Resources Investigations Report 02-4033 GROUND-WATER WATER TABLE CATCHMENT Undifferentiated Lake Surficial Deposits Lake Sediment Breaches in Intermediate Intermediate Confining Unit Confining Unit U.S. Geological Survey Prepared in cooperation with the Southwest Florida Water Management District and the St. Johns River Water Management District Factors Affecting Ground-Water Exchange and Catchment Size for Florida Lakes in Mantled Karst Terrain By T.M. Lee U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Water-Resources Investigations Report 02-4033 Prepared in cooperation with the SOUTHWEST FLORIDA WATER MANAGEMENT DISTRICT and the ST. JOHNS RIVER WATER MANAGEMENT DISTRICT Tallahassee, Florida 2002 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR GALE A. NORTON, Secretary U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY CHARLES G. GROAT, Director The use of firm, trade, and brand names in this report is for identification purposes only and does not constitute endorsement by the U.S. Geological Survey. For additional information Copies of this report can be write to: purchased from: District Chief U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Geological Survey Branch of Information Services Suite 3015 Box 25286 227 N. Bronough Street Denver, CO 80225-0286 Tallahassee, FL 32301 888-ASK-USGS Additional information about water resources in Florida is available on the World Wide Web at http://fl.water.usgs.gov CONTENTS Abstract................................................................................................................................................................................. -

Physical Geography of Southeast Asia

Physical Geography of SE Asia ©2012, TESCCC World Geography Unit 12, Lesson 01 Archipelago • A group of islands. Cordilleras • Parallel mountain ranges and plateaus, that extend into the Indochina Peninsula. Living on the Mainland • Mainland countries include Myanmar, Thailand, Cambodia, Vietnam, and Laos • Laos is a landlocked country • The landscape is characterized by mountains, rivers, river deltas, and plains • The climate includes tropical and mild • The monsoon creates a dry and rainy season ©2012, TESCCC Identify the mainland countries on your map. LAOS VIETNAM MYANMAR THAILAND CAMBODIA Human Settlement on the Mainland • People rely on the rivers that begin in the mountains as a source of water for drinking, transportation, and irrigation • Many people live in small villages • The river deltas create dense population centers • River create rich deposits of sediment that settle along central plains ©2012, TESCCC Major Cities on the Mainland • Myanmar- Yangon (Rangoon), Mandalay • Thailand- Bangkok • Vietnam- Hanoi, Ho Chi Minh City (Saigon) • Cambodia- Phnom Penh ©2012, TESCCC Label the major cities on your map BANGKOK YANGON HO CHI MINH CITY PHNOM PEHN Chao Phraya River • Flows into the Gulf of Thailand, Bangkok is located along the river’s delta Irrawaddy River • Located in Myanmar, Rangoon located along the river Mekong River • Longest river in the region, forms part of the borders of Myanmar, Laos, and Thailand, empties into the South China Sea in Vietnam Label the important rivers and the bodies of water on your map. MEKONG IRRAWADDY CHAO PRAYA ©2012, TESCCC Living on the Islands • The island nations are fragmented • Nations are on islands are made up of island groups. -

Greek-Anatolian Language Contact and the Settlement of Pamphylia

CHRISTINA SKELTON Greek-Anatolian Language Contact and the Settlement of Pamphylia The Ancient Greek dialect of Pamphylia shows extensive influence from the nearby Anatolian languages. Evidence from the linguistics of Greek and Anatolian, sociolinguistics, and the histor- ical and archaeological record suggest that this influence is due to Anatolian speakers learning Greek as a second language as adults in such large numbers that aspects of their L2 Greek became fixed as a part of the main Pamphylian dialect. For this linguistic development to occur and persist, Pamphylia must initially have been settled by a small number of Greeks, and remained isolated from the broader Greek-speaking community while prevailing cultural atti- tudes favored a combined Greek-Anatolian culture. 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 BACKGROUND The Greek-speaking world of the Archaic and Classical periods (ca. ninth through third centuries BC) was covered by a patchwork of different dialects of Ancient Greek, some of them quite different from the Attic and Ionic familiar to Classicists. Even among these varied dialects, the dialect of Pamphylia, located on the southern coast of Asia Minor, stands out as something unusual. For example, consider the following section from the famous Pamphylian inscription from Sillyon: συ Διϝι̣ α̣ ̣ και hιιαροισι Μανεˉ[ς .]υαν̣ hελε ΣελυW[ι]ιυ̣ ς̣ ̣ [..? hι†ια[ρ]α ϝιλ̣ σιι̣ ọς ̣ υπαρ και ανιιας̣ οσα περ(̣ ι)ι[στα]τυ ̣ Wοικ[. .] The author would like to thank Sally Thomason, Craig Melchert, Leonard Neidorf and the anonymous reviewer for their valuable input, as well as Greg Nagy and everyone at the Center for Hellenic Studies for allowing me to use their library and for their wonderful hospitality during the early stages of pre- paring this manuscript. -

December-2016.Pdf

the hollstein journal december 2016 It is my great pleasure to write these first few lines introducing our first e-newsletter. Via this medium, which we aim to publish at least twice a year, we will keep you informed about various Hollstein projects: more in depth information about some of our current projects, new research, publication schedules, as well as other activities connected to Dutch and Flemish and German prints before 1700. In this first issue you will be introduced by Ad Stijnman to Johannes Teyler and the à la poupée printing technique. These volumes to be published in our series The New Hollstein Dutch & Flemish Etchings, Engravings and Woodcuts, 1450-1700 will be the first ever to be in full colour. Some of our previous volumes on the oeuvres of Hendrick Goltzius and Frans Floris already included a few colour plates but Teyler’s substantial oeuvre covers every colour of the rainbow. Marjolein Leesberg will discuss Gerard and Cornelis de Jode. Her research on the De Jode dynasty resulted in such a wealth of new material that we decided to divide The New Hollstein Dutch & Flemish volumes into two separate publications. The first will cover Gerard and Cornelis de Jode and the second following comprises the subsequent family members Pieter de Jode I, Pieter de Jode II, and Arnold de Jode. With the end of the year quickly approaching, I, on behalf of the whole team, would like to take the opportunity to wish you a Merry Christmas and a prosperous 2017. Frits Garritsen Director johannes teyler and dutch colour printing 1685-1710 The group of prints compiled for the forthcoming The à la poupée process had been used since 1457,2 New Hollstein volumes concern what are known as usually inking copper plates but also woodblocks in ‘Teyler prints’. -

Paper: Boston Globe, the (MA) Title: WATCHING the WORLD TAKE SHAPE Date: July 5, 2006

Paper: Boston Globe, The (MA) Title: WATCHING THE WORLD TAKE SHAPE Date: July 5, 2006 If we believe 16th-century accounts, Amerigo Vespucci's exploration of what would become known as the Americas mainly involved getting intimate with natives and brawling. But in the midst of all that, it occurred to Vespucci that this wasn't Asia, despite what Christopher Columbus proclaimed when he bumped into Caribbean islands in 1492. "We discovered many lands and almost countless islands . of which our forefathers make absolutely no mention," one account attributed to Vespucci reported. He hypothesized that this was an unknown continent, a "New World." One of the first to take notice was the German cartographer Martin Waldseemuller, who was so impressed by Vespucci's claims that in 1507 he published the first map showing the lands of the Western Hemisphere as a new continent, separate from Asia. "America," he called it, "after Amerigo, it's [sic] discoverer, a man of great ability." We all know the broad outlines of this tale. But "Journeys of the Imagination," an exhibit at the Boston Public Library in Copley Square through Aug. 18, presents a less familiar finale. Near a facsimile of Waldseemuller's 1507 map, the library displays its print of his 1513 revision [SEE ATTACHED CORRECTION]. Waldseemuller had a change of heart about Vespucci's claim. So he stripped his name and reglued North America to Asia. Successors, however, adopted the name America, and it stuck. Drawn from the library's Norman B. Leventhal Map Center, the 40 maps and two globes ranging from tiny book illustrations to 7-foot-wide panoramas, from the late 15th century to today show Europeans and Americans struggling to envision the earth. -

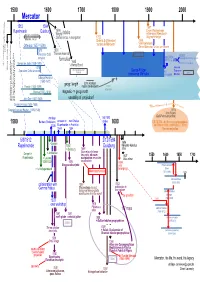

Visio-MERCATOR ENG2.Vsd

1500 1600 1700 1800 1900 2000 Mercator 1512 1594 1897 Rupelmonde Duisburg 1599 tables Lt-gen Wauwermans Italian composite Wright tables article about Mercator in Certain erros in navigation 1752 Biographie belge atlases IATO 1869 middle 15th Century Diderot & d’Alembert “cartes de Mercator” Van Raemdonck Ortelius (1527-1598) Gérard Mercator, sa vie, son oeuvre printing 1570 1600 Theatrum Orbis Thomas Harrriot projection MGRS terrarum 1772 1825 1914 post WWI military grid reference system formulas Johan Lambert Carl Friedrich Gauss Johann Krüger NATO UTM Gerard de Jode (1509-1591) 1645 transverse Mercator transverse Mercator transverse Mercator civil reference system fall of Constantinople Henry Bond 1578 (sphere) (ellipsoid) (ellipsoid) Universal 1492 end of Reconquista Mercatorprojection Transverse Speculum Orbis terrarum formula Gauss-Krüger 1942 grid transverse Mercator developped Mercator Judocus Hondius (1563-1612) + geogr. length John Harrison Plantijn (1520-1589) marine timekeepers use of projection Moretus (1543-1610) magnetic <> geogr north John Dee (1527-1608) useability of projection? 1488 Bartholomeus Dias rounded Cape of Good Hope 1492 Columbus ‘America’ discovered 1498 Vasco da Gama reached India via Africa 1519 – 1522 Magellan around the world Gemma Frisius (1508-1555) 1904 criticism + -- Gaspard van der Heyden (1496-1549) 1974 Arne Peters (Gall-Peters-projection) mariage 5/5/1590 1500 Barbara Shellekens arrested in met Ortelius stroke 1600 CRITICISM - but from non-cartographers - 1536 Rupelmonde in Frankfurt on ethnocentrism, -

ROMANIZATION and SOME CILICIAN CULTS by HUGH ELTON (BIAA)

ROMANIZATION AND SOME CILICIAN CULTS By HUGH ELTON (BIAA) This paper focuses on two sites from central Cilicia in Anatolia, the Cory cian Cave and Kanhdivane, to make some comments about religion and Romanization. From the Corycian Cave, a pair of early third-century AD altars are dedicated to Zeus Korykios, described as Victorious (Epinikios), Triumphant (Tropaiuchos), and the Harvester (Epikarpios), and to Hermes Korykios, also Victorious, Triumphant, and the Harvester. The altars were erected for 'the fruitfulness and brotherly love of the Augusti', suggesting they come from the period before Geta's murder, i.e. between AD 209 and 212. 1 These altars are unremarkable and similar examples are common else where, so these altars can be interpreted as showing the homogenising effect of the Roman Empire. But behind these dedications, however, may lie a re ligious tradition stretching back to the second millennium BC. At the second site, Kanhdivane, a tomb in the west necropolis was accompanied by a fu nerary inscription erected by Marcus Ulpius Knos for himself and his family, probably in the second century AD. Marcus then added, 'but if anyone damages or opens [the tomb] let him pay to the treasury of Zeus 1000 [de narii] and to the Moon (Selene) and to the Sun (Helios) above 1000 [denarii] and let him be subject to the curses also of the Underground Gods (Kata chthoniai Theoi). ' 2 When he wanted to threaten retribution, Knos turned to a local group of gods. As at the Corycian Cave, Knos' actions may preserve traces of pre-Roman practices, though within a Roman framework.