A New Geography of European Power?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

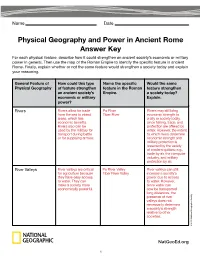

Physical Geography and Power in Ancient Rome Answer

Name Date Physical Geography and Power in Ancient Rome Answer Key For each physical feature, describe how it could strengthen an ancient society’s economic or military power in general. Then use the map of the Roman Empire to identify the specific feature in ancient Rome. Finally, explain whether or not the same feature would strengthen a society today and explain your reasoning. General Feature of How could this type Name the specific Would the same Physical Geography of feature strengthen feature in the Roman feature strengthen an ancient society’s Empire. a society today? economic or military Explain. power? Rivers Rivers allow for trade Po River Rivers may still bring from the sea to inland Tiber River economic strength to areas, which has a city or society today, economic benefits. since fishing, trade, and Rivers also can be protection are offered by used by the military for water. However, the extent transport during battle to which rivers determine or for supplying armies. economic strength and military protection is lessened by the variety of modern options: e.g., trade by air, the computer industry, and military protection by air. River Valleys River valleys are critical Po River Valley River valleys can still for agriculture because Tiber River Valley increase a society’s they have easy access power due to access to water. They can to water. However, make a society more since water can economically powerful. now be transported long distances, the presence of river valleys does not necessarily determine a society’s strength relative to other societies. © 2015 National Geographic Society NatGeoEd.org 1 Physical Geography and Power in Ancient Rome Answer Key, continued General Feature of How could this type Name the specific Would the same Physical Geography of feature strengthen feature in the Roman feature strengthen an ancient society’s Empire. -

Physical Geography of Southeast Asia

Physical Geography of SE Asia ©2012, TESCCC World Geography Unit 12, Lesson 01 Archipelago • A group of islands. Cordilleras • Parallel mountain ranges and plateaus, that extend into the Indochina Peninsula. Living on the Mainland • Mainland countries include Myanmar, Thailand, Cambodia, Vietnam, and Laos • Laos is a landlocked country • The landscape is characterized by mountains, rivers, river deltas, and plains • The climate includes tropical and mild • The monsoon creates a dry and rainy season ©2012, TESCCC Identify the mainland countries on your map. LAOS VIETNAM MYANMAR THAILAND CAMBODIA Human Settlement on the Mainland • People rely on the rivers that begin in the mountains as a source of water for drinking, transportation, and irrigation • Many people live in small villages • The river deltas create dense population centers • River create rich deposits of sediment that settle along central plains ©2012, TESCCC Major Cities on the Mainland • Myanmar- Yangon (Rangoon), Mandalay • Thailand- Bangkok • Vietnam- Hanoi, Ho Chi Minh City (Saigon) • Cambodia- Phnom Penh ©2012, TESCCC Label the major cities on your map BANGKOK YANGON HO CHI MINH CITY PHNOM PEHN Chao Phraya River • Flows into the Gulf of Thailand, Bangkok is located along the river’s delta Irrawaddy River • Located in Myanmar, Rangoon located along the river Mekong River • Longest river in the region, forms part of the borders of Myanmar, Laos, and Thailand, empties into the South China Sea in Vietnam Label the important rivers and the bodies of water on your map. MEKONG IRRAWADDY CHAO PRAYA ©2012, TESCCC Living on the Islands • The island nations are fragmented • Nations are on islands are made up of island groups. -

Greek-Anatolian Language Contact and the Settlement of Pamphylia

CHRISTINA SKELTON Greek-Anatolian Language Contact and the Settlement of Pamphylia The Ancient Greek dialect of Pamphylia shows extensive influence from the nearby Anatolian languages. Evidence from the linguistics of Greek and Anatolian, sociolinguistics, and the histor- ical and archaeological record suggest that this influence is due to Anatolian speakers learning Greek as a second language as adults in such large numbers that aspects of their L2 Greek became fixed as a part of the main Pamphylian dialect. For this linguistic development to occur and persist, Pamphylia must initially have been settled by a small number of Greeks, and remained isolated from the broader Greek-speaking community while prevailing cultural atti- tudes favored a combined Greek-Anatolian culture. 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 BACKGROUND The Greek-speaking world of the Archaic and Classical periods (ca. ninth through third centuries BC) was covered by a patchwork of different dialects of Ancient Greek, some of them quite different from the Attic and Ionic familiar to Classicists. Even among these varied dialects, the dialect of Pamphylia, located on the southern coast of Asia Minor, stands out as something unusual. For example, consider the following section from the famous Pamphylian inscription from Sillyon: συ Διϝι̣ α̣ ̣ και hιιαροισι Μανεˉ[ς .]υαν̣ hελε ΣελυW[ι]ιυ̣ ς̣ ̣ [..? hι†ια[ρ]α ϝιλ̣ σιι̣ ọς ̣ υπαρ και ανιιας̣ οσα περ(̣ ι)ι[στα]τυ ̣ Wοικ[. .] The author would like to thank Sally Thomason, Craig Melchert, Leonard Neidorf and the anonymous reviewer for their valuable input, as well as Greg Nagy and everyone at the Center for Hellenic Studies for allowing me to use their library and for their wonderful hospitality during the early stages of pre- paring this manuscript. -

5Hjxodwru\ 5Hirup Lq +Xqjdu\

5HJXODWRU\ 5HIRUP LQ +XQJDU\ 5HJXODWRU\ 5HIRUP LQ WKH (OHFWULFLW\ 6HFWRU ORGANISATION FOR ECONOMIC CO-OPERATION AND DEVELOPMENT Pursuant to Article 1 of the Convention signed in Paris on 14th December 1960, and which came into force on 30th September 1961, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) shall promote policies designed: to achieve the highest sustainable economic growth and employment and a rising standard of living in Member countries, while maintaining financial stability, and thus to contribute to the development of the world economy; to contribute to sound economic expansion in Member as well as non-member countries in the process of economic development; and to contribute to the expansion of world trade on a multilateral, non-discriminatory basis in accordance with international obligations. The original Member countries of the OECD are Austria, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, France, Germany, Greece, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey, the United Kingdom and the United States. The following countries became Members subsequently through accession at the dates indicated hereafter: Japan (28th April 1964), Finland (28th January 1969), Australia (7th June 1971), New Zealand (29th May 1973), Mexico (18th May 1994), the Czech Republic (21st December 1995), Hungary (7th May 1996), Poland (22nd November 1996), Korea (12th December 1996) and the Slovak Republic (14th December 2000). The Commission of the European Communities takes part in the work of the OECD (Article 13 of the OECD Convention). Publié en français sous le titre : LA RÉFORME DE LA RÉGLEMENTATION DANS LE SECTEUR DE L'ÉLECTRICITÉ © OECD 2000. Permission to reproduce a portion of this work for non-commercial purposes or classroom use should be obtained through the Centre français d’exploitation du droit de copie (CFC), 20, rue des Grands-Augustins, 75006 Paris, France, tel. -

THE LYCIAN PEOPLE and THEIR ENVIRONMENT 1 Geography And

CHAP'IERTWO THE LYCIAN PEOPLE AND THEIR ENVIRONMENT 1 Geography and communications in Lycia1 Lycia lies on the south-west coast of Asia Minor, between Caria and Pam phylia. At the period of its smallest extent, at the time of the Persian con quest, the Lycian state covered an area comparable in size to Attica, ex tending over most of the territory of the Xanthos valley, probably as far north as Araxa, more than forty kilometres away from Xanthos, and nearly fifty from the Mediterranean; Bryce has argued that to Homer 'Lycia' meant no more than the Xanthos valley. 2 At its largest, under Perikle of Limyra (pp. 154-70), the Lycian state was comparable in size to the south ern Peloponnese (i.e. Laconia and Messenia), stretching from Phaselis in the east to Telemessos in the north-west, nearly a hundred and thirty kilo metres as the crow flies, and included a large section of southern Milyas, if not all of it (p. 20). It is separated from its neighbours by high mountains which hampered movement in antiquity. 3 This remoteness continued into modern times-when Bean first visited the area in 1946 he found a country where tractors were unknown, and: When I asked, 'What do you do in the winter?', the answer was, 'We sit'.4 Three great chains determine access to and within Lycia. In the west two spurs of the western Tauros, the Boncuk Daglan and the Baba Dag1 (this latter being ancient Mt. Kragos and Mt. Antikragos) restrict access to Ly cia to the pass between them, east of Telemessos. -

Ground-Water Resources of the Bengasi Area, Cyrenaica, United Kingdom of Libya

Ground-Water Resources of the Bengasi Area, Cyrenaica, United Kingdom of Libya GEOLOGICAL SURVEY WATER-SUPPLY PAPER 1757-B Prepared under the auspices of the United States Operations Mission to Libya, the United States Corps of Engineers, and the Government of Libya BBQPERTY OF U.S.GW«r..GlCAL SURVEY JRENTON, NEW JEST.W Ground-Water Resources of the Bengasi Area Cyrenaica, United Kingdom of Libya By W. W. DOYEL and F. J. MAGUIRE CONTRIBUTIONS TO THE HYDROLOGY OF AFRICA AND THE MEDITERRANEAN REGION GEOLOGICAL SURVEY WATER-SUPPLY PAPER 1757-B Prepared under the auspices of the United States Operations Mission to Libya, the United States Corps of Engineers, and the Government of Libya UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1964 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR STEWART L. UDALL, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Thomas B. Nolan, Director For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 CONTENTS Page Abstract _ _______________-__--__-_______--__--_-__---_-------_--- Bl Introduction______-______--__-_-____________--------_-----------__ 1 Location and extent of area-----_______----___--_-------------_- 1 Purpose and scope of investigation---______-_______--__-------__- 3 Acknowledgments __________________________-__--_-----_--_____ 3 Geography___________--_---___-_____---____------------_-___---_- 5 General features.._-_____-___________-_-_____--_-_---------_-_- 5 Topography and drainage_______________________--_-------.-_- 6 Climate.____________________.__----- - 6 Geology____________________-________________________-___----__-__ 8 Ground water____._____________-____-_-______-__-______-_--_--__ 10 Bengasi municipal supply_____________________________________ 12 Other water supplies___________________-______-_-_-___-_--____- 14 Test drilling....______._______._______.___________ 15 Conclusions. -

Earth/Environmental (2014) Released Final Exam

Released Items Fall 2014 NC Final Exam Earth/Environmental Science RELEASED Public Schools of North Carolina Student Booklet State Board of Education Department of Public Instruction Raleigh, North Carolina 27699-6314 Copyrightã 2014 by the North Carolina Department of Public Instruction. All rights reserved. E ARTH/ENVIRONMENTAL S CIENCE — R ELEASED I TEMS 1 Cracks in rocks widen as water in them freezes and thaws. How does this affect the surface of the Earth? A It reduces the rates of soil formation. B It changes the chemical composition of the rocks. C It exposes rocks to increased rates of erosion and weathering. D It limits the exposure of rocks to acid precipitation. 2 How can urbanization affect a local area? A It can increase the number of invasive species in an area. B It can decrease the risk of water pollution in an area. C It can increase the risk of flooding in an area. D It can decrease the need for natural resources in an area. 3 Which is a farming technique that could improve the soil and the environment? A using fueled machines that will turn the soil continuously B creating undisturbed layers of mulch in the soil C placing inorganic chemical fertilizers in the soil D irrigating the RELEASEDsoil with salty water 1 Go to the next page. E ARTH/ENVIRONMENTAL S CIENCE — R ELEASED I TEMS 4 Subsurface ocean currents continually circulate from the warm waters near the equator to the colder waters in other parts of the world. What is the main cause of these currents? A differences in the topography along the ocean floor B differences -

Interactions of Land and Water in Europe

Name Date Interactions of Land and Water in Europe Read the following passage two times. Read once for understanding. As you read the second time, underline or highlight each proper name of a physical feature of Europe. The interactions of land and water in Europe have shaped the geography of Europe. These interactions have also shaped the lives of the people who live there. The continent of Europe is nearly 10,359,952 square kilometers (4,000,000 square miles). Its finger-like peninsulas extend into the Arctic and Atlantic Oceans and the Baltic and Mediterranean Seas. The oceans and seas lie to the north, south, and west of the continent. Only the eastern edge of the continent is landlocked. It is firmly attached to its larger neighbor, Asia, along Russia and Kazakhstan’s low Ural Mountain range. Mountains, rivers, and seacoasts dominate the landscape from north to south and east to west. Europe is the only continent with no large deserts. The Scandinavian Peninsula and islands of Great Britain are partially covered with eroded mountains laced with fjords and lakes carved out by ancient glaciers. The northern edge of Europe lies in the frozen, treeless tundra biome. But forests once covered more than 80 percent of the continent. Thousands of years of clearing the land for farming and building towns and cities has left only a few large forest areas remaining in Scandinavia, Germany, France, Spain, and Russia. Warm, wet air from the Atlantic Ocean allowed agriculture, or farming, to thrive in chilly northern Europe. This is especially true on the North European Plain, which stretches all the way from France and southern England to Russia. -

What Is the Importance of Islands to Environmental Conservation?

Environmental Conservation (2017) 44 (4): 311–322 C Foundation for Environmental Conservation 2017 doi:10.1017/S0376892917000479 What is the importance of islands to environmental THEMATIC SECTION Humans and Island conservation? Environments CHRISTOPH KUEFFER∗ 1 AND KEALOHANUIOPUNA KINNEY2 1Institute of Integrative Biology, ETH Zurich, Universitätsstrasse 16, CH-8092 Zurich, Switzerland and 2Institute of Pacifc Islands Forestry, US Forest Service, 60 Nowelo St. Hilo, HI, USA Date submitted: 15 May 2017; Date accepted: 8 August 2017 SUMMARY islands of the world’s oceans, we cover both islands close to continents and others isolated far out in the oceans, and the This article discusses four features of islands that make full range from small to very large islands. Small and isolated them places of special importance to environmental islands represent unique cultural and biological values and the conservation. First, investment in island conservation environmental challenges of insularity in its most pronounced is both urgent and cost-effective. Islands are form. However, as we will demonstrate, all islands and island threatened hotspots of diversity that concentrate people share enough come concerns to consider them together unique cultural, biological and geophysical values, (Baldacchino 2007; Royle 2008; Gillespie & Clague 2009; and they form the basis of the livelihoods of Baldacchino & Niles 2011; Royle 2014). millions of islanders. Second, islands are paradigmatic Islands are hotspots of cultural, biological and geophysical places of human–environment relationships. Island diversity, and as such they form the basis of the livelihoods livelihoods have a long tradition of existing within of millions of islanders (Menard 1986; Nunn 1994; Royle spatial, ecological and ultimately social boundaries 2008; Gillespie & Clague 2009; Royle 2014; Kueffer et al. -

A Review of the Three Waves of International Relations Small State Literature

Pacific Dynamics: Vol 5 (1) 2021 Journal of Interdisciplinary Research http://pacificdynamics.nz Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 ISSN: 2463-641X DOI : http://dx.doi.org/10.26021/10639 Breaking the paradigm(s): A review of the three waves of international relations small state literature Jeffrey Willis* Independent Researcher Abstract Mainstream international relations (IR) literature has long treated small states as marginal actors who exist on the periphery of global affairs. For many years, scholars have struggled to conclusively define the category of small statehood. Additionally, IR’s privileging of the theoretical paradigms of realism and neorealism when analyzing small state issues, has meant that, until recently, small states have been conceptualized as actors that struggle to make proactive foreign policy choices on their own terms. Despite this, small states, and particularly small island states in the Pacific region, appear to have many opportunities to engage in vibrant foreign policy endeavours in the present day. This article offers a review of small state IR literature, with a particular focus on small state foreign policy issues. It begins by reviewing the various approaches to defining small statehood, before turning to a review of how small state issues have been treated in broader IR. It posits that the small state IR literature can usefully be broken down into three distinct time periods— 1959–1979, 1979–1992, and 1992–present—and reviews the literature within that framework, drawing out the theoretical through lines -

Environmental Science in the Course of Different Levels

THIS PAGE IS BLANK NEW AGE INTERNATIONAL (P) LIMITED, PUBLISHERS New Delhi · Bangalore · Chennai · Cochin · Guwahati · Hyderabad Jalandhar · Kolkata · Lucknow · Mumbai · Ranchi PUBLISHING FOR ONE WORLD Visit us at www.newagepublishers.com Copyright © 2006 New Age International (P) Ltd., Publishers Published by New Age International (P) Ltd., Publishers All rights reserved. No part of this ebook may be reproduced in any form, by photostat, microfilm, xerography, or any other means, or incorporated into any information retrieval system, electronic or mechanical, without the written permission of the publisher. All inquiries should be emailed to [email protected] ISBN (10) : 81-224-2330-2 ISBN (13) : 978-81-224-2330-3 PUBLISHING FOR ONE WORLD NEW AGE INTERNATIONAL (P) LIMITED, PUBLISHERS 4835/24, Ansari Road, Daryaganj, New Delhi - 110002 Visit us at www.newagepublishers.com Education is a process of development which includes the three major activities, teaching, training and instruction. Teaching is social as well as a professional activity. It is science as well as art. Modern education is not in a sphere but it has a long and large area of study. Now a days most part of the world population is facing different problems related with the nature and they are studying the solutions to save the nature and global problems, but on the second hand we even today do not try to understand our local problems related to the nature. So for the awareness of the problems of P nature and pollution the higher education commission has suggested to add the Environmental Science in the course of different levels. -

168 2Nd Issue 2015

ISSN 0019–1043 Ice News Bulletin of the International Glaciological Society Number 168 2nd Issue 2015 Contents 2 From the Editor 25 Annals of Glaciology 56(70) 5 Recent work 25 Annals of Glaciology 57(71) 5 Chile 26 Annals of Glaciology 57(72) 5 National projects 27 Report from the New Zealand Branch 9 Northern Chile Annual Workshop, July 2015 11 Central Chile 29 Report from the Kathmandu Symposium, 13 Lake district (37–41° S) March 2015 14 Patagonia and Tierra del Fuego (41–56° S) 43 News 20 Antarctica International Glaciological Society seeks a 22 Abbreviations new Chief Editor and three new Associate 23 International Glaciological Society Chief Editors 23 Journal of Glaciology 45 Glaciological diary 25 Annals of Glaciology 56(69) 48 New members Cover picture: Khumbu Glacier, Nepal. Photograph by Morgan Gibson. EXCLUSION CLAUSE. While care is taken to provide accurate accounts and information in this Newsletter, neither the editor nor the International Glaciological Society undertakes any liability for omissions or errors. 1 From the Editor Dear IGS member It is now confirmed. The International Glacio be moving from using the EJ Press system to logical Society and Cambridge University a ScholarOne system (which is the one CUP Press (CUP) have joined in a partnership in uses). For a transition period, both online which CUP will take over the production and submission/review systems will run in parallel. publication of our two journals, the Journal Submissions will be twotiered – of Glaciology and the Annals of Glaciology. ‘Papers’ and ‘Letters’. There will no longer This coincides with our journals becoming be a distinction made between ‘General’ fully Gold Open Access on 1 January 2016.