Greek-Anatolian Language Contact and the Settlement of Pamphylia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Impact of Hittite and Tocharian: Rethinking Indo-European in the 20Th Century and Beyond

The Impact of Hittite and Tocharian: Rethinking Indo-European in the 20th Century and Beyond The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Jasanoff, Jay. 2017. The Impact of Hittite and Tocharian: Rethinking Indo-European in the 20th Century and Beyond. In Handbook of Comparative and Historical Indo-European Linguistics, edited by Jared Klein, Brian Joseph, and Matthias Fritz, 31-53. Munich: Walter de Gruyter. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:41291502 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA 18. The Impact of Hittite and Tocharian ■■■ 35 18. The Impact of Hittite and Tocharian: Rethinking Indo-European in the Twentieth Century and Beyond 1. Two epoch-making discoveries 4. Syntactic impact 2. Phonological impact 5. Implications for subgrouping 3. Morphological impact 6. References 1. Two epoch-making discoveries The ink was scarcely dry on the last volume of Brugmann’s Grundriß (1916, 2nd ed., Vol. 2, pt. 3), so to speak, when an unexpected discovery in a peripheral area of Assyriol- ogy portended the end of the scholarly consensus that Brugmann had done so much to create. Hrozný, whose Sprache der Hethiter appeared in 1917, was not primarily an Indo-Europeanist, but, like any trained philologist of the time, he could see that the cuneiform language he had deciphered, with such features as an animate nom. -

Tlos, Oinoanda and the Hittite Invasion of the Lukka Lands. Some Thoughts on the History of North-Western Lycia in the Late Bronze and Iron Ages

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2014 Tlos, Oinoanda and the Hittite Invasion of the Lukka lands: Some Thoughts on the History of North-Western Lycia in the Late Bronze and Iron Ages Gander, Max DOI: https://doi.org/10.1515/klio-2014-0039 Posted at the Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich ZORA URL: https://doi.org/10.5167/uzh-119374 Journal Article Published Version Originally published at: Gander, Max (2014). Tlos, Oinoanda and the Hittite Invasion of the Lukka lands: Some Thoughts on the History of North-Western Lycia in the Late Bronze and Iron Ages. Klio. Beiträge zur Alten Geschichte, 96(2):369-415. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1515/klio-2014-0039 Klio 2014; 96(2): 369–415 Max Gander Tlos, Oinoanda and the Hittite Invasion of the Lukka lands. Some Thoughts on the History of North-Western Lycia in the Late Bronze and Iron Ages Summary: The present article contains observations on the invasion of Lycia by the Hittite king Tudhaliya IV as described in the Yalburt inscription. The author questions the commonly found identification of the land of VITIS/Wiyanwanda with the city of Oinoanda on account of the problems raised by the reading of the sign VITIS as well as of archaeological and strategical observations. With the aid of Lycian and Greek inscriptions the author argues that the original Wiya- nawanda/Oinoanda was located further south than the city commonly known as Oinoanda situated above İncealiler. These insights lead to a reassessment of the Hittite-Luwian sources concerning the conquest of Lycia. -

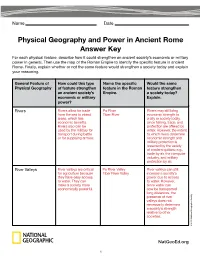

Physical Geography and Power in Ancient Rome Answer

Name Date Physical Geography and Power in Ancient Rome Answer Key For each physical feature, describe how it could strengthen an ancient society’s economic or military power in general. Then use the map of the Roman Empire to identify the specific feature in ancient Rome. Finally, explain whether or not the same feature would strengthen a society today and explain your reasoning. General Feature of How could this type Name the specific Would the same Physical Geography of feature strengthen feature in the Roman feature strengthen an ancient society’s Empire. a society today? economic or military Explain. power? Rivers Rivers allow for trade Po River Rivers may still bring from the sea to inland Tiber River economic strength to areas, which has a city or society today, economic benefits. since fishing, trade, and Rivers also can be protection are offered by used by the military for water. However, the extent transport during battle to which rivers determine or for supplying armies. economic strength and military protection is lessened by the variety of modern options: e.g., trade by air, the computer industry, and military protection by air. River Valleys River valleys are critical Po River Valley River valleys can still for agriculture because Tiber River Valley increase a society’s they have easy access power due to access to water. They can to water. However, make a society more since water can economically powerful. now be transported long distances, the presence of river valleys does not necessarily determine a society’s strength relative to other societies. © 2015 National Geographic Society NatGeoEd.org 1 Physical Geography and Power in Ancient Rome Answer Key, continued General Feature of How could this type Name the specific Would the same Physical Geography of feature strengthen feature in the Roman feature strengthen an ancient society’s Empire. -

Physical Geography of Southeast Asia

Physical Geography of SE Asia ©2012, TESCCC World Geography Unit 12, Lesson 01 Archipelago • A group of islands. Cordilleras • Parallel mountain ranges and plateaus, that extend into the Indochina Peninsula. Living on the Mainland • Mainland countries include Myanmar, Thailand, Cambodia, Vietnam, and Laos • Laos is a landlocked country • The landscape is characterized by mountains, rivers, river deltas, and plains • The climate includes tropical and mild • The monsoon creates a dry and rainy season ©2012, TESCCC Identify the mainland countries on your map. LAOS VIETNAM MYANMAR THAILAND CAMBODIA Human Settlement on the Mainland • People rely on the rivers that begin in the mountains as a source of water for drinking, transportation, and irrigation • Many people live in small villages • The river deltas create dense population centers • River create rich deposits of sediment that settle along central plains ©2012, TESCCC Major Cities on the Mainland • Myanmar- Yangon (Rangoon), Mandalay • Thailand- Bangkok • Vietnam- Hanoi, Ho Chi Minh City (Saigon) • Cambodia- Phnom Penh ©2012, TESCCC Label the major cities on your map BANGKOK YANGON HO CHI MINH CITY PHNOM PEHN Chao Phraya River • Flows into the Gulf of Thailand, Bangkok is located along the river’s delta Irrawaddy River • Located in Myanmar, Rangoon located along the river Mekong River • Longest river in the region, forms part of the borders of Myanmar, Laos, and Thailand, empties into the South China Sea in Vietnam Label the important rivers and the bodies of water on your map. MEKONG IRRAWADDY CHAO PRAYA ©2012, TESCCC Living on the Islands • The island nations are fragmented • Nations are on islands are made up of island groups. -

Poison King: the Life and Legend of Mithradates the Great, Rome's

Copyrighted Material Kill em All, and Let the Gods Sort em Out IN SPRING of 88 BC, in dozens of cities across Anatolia (Asia Minor, modern Turkey), sworn enemies of Rome joined a secret plot. On an appointed day in one month’s time, they vowed to kill every Roman man, woman, and child in their territories. e conspiracy was masterminded by King Mithradates the Great, who communicated secretly with numerous local leaders in Rome’s new Province of Asia. (“Asia” at this time referred to lands from the eastern Aegean to India; Rome’s Province of Asia encompassed western Turkey.) How Mithradates kept the plot secret remains one of the great intelli- gence mysteries of antiquity. e conspirators promised to round up and slay all the Romans and Italians living in their towns, including women and children and slaves of Italian descent. ey agreed to confiscate the Romans’ property and throw the bodies out to the dogs and crows. Any- one who tried to warn or protect Romans or bury their bodies was to be harshly punished. Slaves who spoke languages other than Latin would be spared, and those who joined in the killing of their masters would be rewarded. People who murdered Roman moneylenders would have their debts canceled. Bounties were offered to informers and killers of Romans in hiding.1 e deadly plot worked perfectly. According to several ancient histo- rians, at least 80,000—perhaps as many as 150,000—Roman and Italian residents of Anatolia and Aegean islands were massacred on that day. e figures are shocking—perhaps exaggerated—but not unrealistic. -

Cappadocia and Cappadocians in the Hellenistic, Roman and Early

Dokuz Eylül University – DEU The Research Center for the Archaeology of Western Anatolia – EKVAM Colloquia Anatolica et Aegaea Congressus internationales Smyrnenses X Cappadocia and Cappadocians in the Hellenistic, Roman and Early Byzantine periods An international video conference on the southeastern part of central Anatolia in classical antiquity May 14-15, 2020 / Izmir, Turkey Edited by Ergün Laflı Izmir 2020 Last update: 04/05/2020. 1 Cappadocia and Cappadocians in the Hellenistic, Roman and Early Byzantine periods. Papers presented at the international video conference on the southeastern part of central Anatolia in classical antiquity, May 14-15, 2020 / Izmir, Turkey, Colloquia Anatolica et Aegaea – Acta congressus communis omnium gentium Smyrnae. Copyright © 2020 Ergün Laflı (editor) All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission from the editor. ISBN: 978-605-031-211-9. Page setting: Ergün Laflı (Izmir). Text corrections and revisions: Hugo Thoen (Deinze / Ghent). Papers, presented at the international video conference, entitled “Cappadocia and Cappadocians in the Hellenistic, Roman and Early Byzantine periods. An international video conference on the southeastern part of central Anatolia in classical antiquity” in May 14–15, 2020 in Izmir, Turkey. 36 papers with 61 pages and numerous colourful figures. All papers and key words are in English. 21 x 29,7 cm; paperback; 40 gr. quality paper. Frontispiece. A Roman stele with two portraits in the Museum of Kırşehir; accession nos. A.5.1.95a-b (photograph by E. -

The Carian Language HANDBOOK of ORIENTAL STUDIES SECTION ONE the NEAR and MIDDLE EAST

The Carian Language HANDBOOK OF ORIENTAL STUDIES SECTION ONE THE NEAR AND MIDDLE EAST Ancient Near East Editor-in-Chief W. H. van Soldt Editors G. Beckman • C. Leitz • B. A. Levine P. Michalowski • P. Miglus Middle East R. S. O’Fahey • C. H. M. Versteegh VOLUME EIGHTY-SIX The Carian Language by Ignacio J. Adiego with an appendix by Koray Konuk BRILL LEIDEN • BOSTON 2007 This book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Adiego Lajara, Ignacio-Javier. The Carian language / by Ignacio J. Adiego ; with an appendix by Koray Konuk. p. cm. — (Handbook of Oriental studies. Section 1, The Near and Middle East ; v. 86). Includes bibliographical references. ISBN-13 : 978-90-04-15281-6 (hardback) ISBN-10 : 90-04-15281-4 (hardback) 1. Carian language. 2. Carian language—Writing. 3. Inscriptions, Carian—Egypt. 4. Inscriptions, Carian—Turkey—Caria. I. Title. II. P946.A35 2006 491’.998—dc22 2006051655 ISSN 0169-9423 ISBN-10 90 04 15281 4 ISBN-13 978 90 04 15281 6 © Copyright 2007 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill Hotei Publishers, IDC Publishers, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, and VSP. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by Brill provided that the appropriate fees are paid directly to The Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Suite 910, Danvers, MA 01923, USA. -

Mortem Et Gloriam Army Lists Use the Army Lists to Create Your Own Customised Armies Using the Mortem Et Gloriam Army Builder

Army Lists Syria and Asia Minor Contents Asiatic Greek 670 to 129 BCE Lycian 525 to 300 BCE Bithynian 434 to 74 BCE Armenian 330 BCE to 627 CE Asiatic Successor 323 to 280 BCE Cappadocian 300 BCE to 17 CE Attalid Pergamene 282 to 129 BCE Galatian 280 to 62 BCE Early Seleucid 279 to 167 BCE Seleucid 166 to 129 BCE Commagene 163 BCE to 72 CE Late Seleucid 128 to 56 BCE Pontic 110 to 47 BCE Palmyran 258 CE to 273 CE Version 2020.02: 1st January 2020 © Simon Hall Creating an army with the Mortem et Gloriam Army Lists Use the army lists to create your own customised armies using the Mortem et Gloriam Army Builder. There are few general rules to follow: 1. An army must have at least 2 generals and can have no more than 4. 2. You must take at least the minimum of any troops noted and may not go beyond the maximum of any. 3. No army may have more than two generals who are Talented or better. 4. Unless specified otherwise, all elements in a UG must be classified identically. Unless specified otherwise, if an optional characteristic is taken, it must be taken by all the elements in the UG for which that optional characteristic is available. 5. Any UGs can be downgraded by one quality grade and/or by one shooting skill representing less strong, tired or understrength troops. If any bases are downgraded all in the UG must be downgraded. So Average-Experienced skirmishers can always be downgraded to Poor-Unskilled. -

A Literary Sources

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-82860-4 — The Hellenistic World from Alexander to the Roman Conquest 2nd Edition Index More Information Index A Literary sources Livy XXVI.24.7–15: 77 (a); XXIX.12.11–16: 80; XXXI.44.2–9: 11 Aeschines III.132–4: 82; XXXIII.38: 195; XXXVII.40–1: Appian, Syrian Wars 52–5, 57–8, 62–3: 203; XXXVIII.34: 87; 57 XXXIX.24.1–4: 89; XLI.20: 209 (b); ‘Aristeas to Philocrates’ I.9–11 and XLII.29–30.7: 92; XLII.51: 94; 261 V.35–40: XLV.29.3–30 and 32.1–7: 96 15 [Aristotle] Oeconomica II.2.33: I Maccabees 1.1–9: 24; 1.10–25 and 5 7 Arrian, Alexander I.17: ; II.14: ; 41–56: 217; 15.1–9: 221 8 9 III.1.5–2.2: (a); III.3–4: ; II Maccabees 3.1–3: 216 12 13 IV.10.5–12.5: ; V.28–29.1: ; Memnon, FGrH 434 F 11 §§5.7–11: 159 14 20 V1.27.3–5: ; VII.1.1–4: ; Menander, The Sicyonian lines 3–15: 104 17 18 VII.4.4–5: ; VII.8–9 and 11: Menecles of Barca FGrHist 270F9:322 26 Arrian, FGrH 156 F 1, §§1–8: (a); F 9, Pausanias I.7: 254; I.9.4: 254; I.9.5–10: 30 §§34–8: 56; I.25.3–6: 28; VII.16.7–17.1: Athenaeus, Deipnosophistae V.201b–f, 100 258 43 202f–203e: ; VI.253b–f: Plutarch, Agis 5–6.1 and 7.5–8: 69 23 Augustine, City of God 4.4: Alexander 10.6–11: 3 (a); 15: 4 (a); Demetrius of Phalerum, FGrH 228 F 39: 26.3–10: 8 (b); 68.3: cf. -

Homer's Iliad Via the Movie Troy (2004)

23 November 2017 Homer’s Iliad via the Movie Troy (2004) PROFESSOR EDITH HALL One of the most successful movies of 2004 was Troy, directed by Wolfgang Petersen and starring Brad Pitt as Achilles. Troy made more than $497 million worldwide and was the 8th- highest-grossing film of 2004. The rolling credits proudly claim that the movie is inspired by the ancient Greek Homeric epic, the Iliad. This was, for classical scholars, an exciting claim. There have been blockbuster movies telling the story of Troy before, notably the 1956 glamorous blockbuster Helen of Troy starring Rossana Podestà, and a television two-episode miniseries which came out in 2003, directed by John Kent Harrison. But there has never been a feature film announcing such a close relationship to the Iliad, the greatest classical heroic action epic. The movie eagerly anticipated by those of us who teach Homer for a living because Petersen is a respected director. He has made some serious and important films. These range from Die Konsequenz (The Consequence), a radical story of homosexual love (1977), to In the Line of Fire (1993) and Air Force One (1997), political thrillers starring Clint Eastwood and Harrison Ford respectively. The Perfect Storm (2000) showed that cataclysmic natural disaster and special effects spectacle were also part of Petersen’s repertoire. His most celebrated film has probably been Das Boot (The Boat) of 1981, the story of the crew of a German U- boat during the Battle of the Atlantic in 1941. The finely judged and politically impartial portrayal of ordinary men, caught up in the terror and tedium of war, suggested that Petersen, if anyone, might be able to do some justice to the Homeric depiction of the Trojan War in the Iliad. -

THE INDO-EUROPEAN FAMILY — the LINGUISTIC EVIDENCE by Brian D

THE INDO-EUROPEAN FAMILY — THE LINGUISTIC EVIDENCE by Brian D. Joseph, The Ohio State University 0. Introduction A stunning result of linguistic research in the 19th century was the recognition that some languages show correspondences of form that cannot be due to chance convergences, to borrowing among the languages involved, or to universal characteristics of human language, and that such correspondences therefore can only be the result of the languages in question having sprung from a common source language in the past. Such languages are said to be “related” (more specifically, “genetically related”, though “genetic” here does not have any connection to the term referring to a biological genetic relationship) and to belong to a “language family”. It can therefore be convenient to model such linguistic genetic relationships via a “family tree”, showing the genealogy of the languages claimed to be related. For example, in the model below, all the languages B through I in the tree are related as members of the same family; if they were not related, they would not all descend from the same original language A. In such a schema, A is the “proto-language”, the starting point for the family, and B, C, and D are “offspring” (often referred to as “daughter languages”); B, C, and D are thus “siblings” (often referred to as “sister languages”), and each represents a separate “branch” of the family tree. B and C, in turn, are starting points for other offspring languages, E, F, and G, and H and I, respectively. Thus B stands in the same relationship to E, F, and G as A does to B, C, and D. -

Archaeology and History of Lydia from the Early Lydian Period to Late Antiquity (8Th Century B.C.-6Th Century A.D.)

Dokuz Eylül University – DEU The Research Center for the Archaeology of Western Anatolia – EKVAM Colloquia Anatolica et Aegaea Congressus internationales Smyrnenses IX Archaeology and history of Lydia from the early Lydian period to late antiquity (8th century B.C.-6th century A.D.). An international symposium May 17-18, 2017 / Izmir, Turkey ABSTRACTS Edited by Ergün Laflı Gülseren Kan Şahin Last Update: 21/04/2017. Izmir, May 2017 Websites: https://independent.academia.edu/TheLydiaSymposium https://www.researchgate.net/profile/The_Lydia_Symposium 1 This symposium has been dedicated to Roberto Gusmani (1935-2009) and Peter Herrmann (1927-2002) due to their pioneering works on the archaeology and history of ancient Lydia. Fig. 1: Map of Lydia and neighbouring areas in western Asia Minor (S. Patacı, 2017). 2 Table of contents Ergün Laflı, An introduction to Lydian studies: Editorial remarks to the abstract booklet of the Lydia Symposium....................................................................................................................................................8-9. Nihal Akıllı, Protohistorical excavations at Hastane Höyük in Akhisar………………………………10. Sedat Akkurnaz, New examples of Archaic architectural terracottas from Lydia………………………..11. Gülseren Alkış Yazıcı, Some remarks on the ancient religions of Lydia……………………………….12. Elif Alten, Revolt of Achaeus against Antiochus III the Great and the siege of Sardis, based on classical textual, epigraphic and numismatic evidence………………………………………………………………....13. Gaetano Arena, Heleis: A chief doctor in Roman Lydia…….……………………………………....14. Ilias N. Arnaoutoglou, Κοινὸν, συμβίωσις: Associations in Hellenistic and Roman Lydia……….……..15. Eirini Artemi, The role of Ephesus in the late antiquity from the period of Diocletian to A.D. 449, the “Robber Synod”.……………………………………………………………………….………...16. Natalia S. Astashova, Anatolian pottery from Panticapaeum…………………………………….17-18. Ayşegül Aykurt, Minoan presence in western Anatolia……………………………………………...19.