THE LYCIAN PEOPLE and THEIR ENVIRONMENT 1 Geography And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Georgy Kantor

Georgy Kantor Lycia et Pamphylia: A Social and Institutional History The project which I am proposing to undertake is a social and institutional history of the Roman province of Lycia and Pamphylia, from the process of establishment of Roman rule in the region in the late Republic and the Julio-Claudian period to the coming of Christianity and the separation of the constituent parts of the province in the early fourth century AD. The project aims at utilising different kinds of evidence – documentary, archaeological, numismatic, literary. Several factors combine to make such a study worthwhile. The isolated nature of the region, separated as it is by mountain ranges from the rest of Anatolia, and the fact that, with a very brief interruption, it has been a single administrative unit for more than two centuries, from the principate of Claudius to at least AD 312, allow us to treat it as a meaningful object of regional history. But below this unity there were striking distinctions between its different parts. In the course of my doctoral work on Roman and local law in the provinces of Asia Minor, I have found preliminary evidence to indicate that the ways in which Pamphylia and Lycia were governed by Rome were different in many crucial aspects. My project will thus provide an opportunity to study two models of Roman rule within one province, and it is at this level that we can best understand how Roman imperial structures worked and contribute to the ongoing discussion (re-opened by recent works of S. Dmitriev and C. -

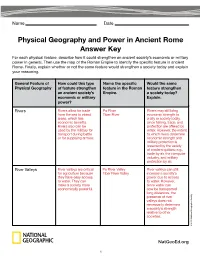

Physical Geography and Power in Ancient Rome Answer

Name Date Physical Geography and Power in Ancient Rome Answer Key For each physical feature, describe how it could strengthen an ancient society’s economic or military power in general. Then use the map of the Roman Empire to identify the specific feature in ancient Rome. Finally, explain whether or not the same feature would strengthen a society today and explain your reasoning. General Feature of How could this type Name the specific Would the same Physical Geography of feature strengthen feature in the Roman feature strengthen an ancient society’s Empire. a society today? economic or military Explain. power? Rivers Rivers allow for trade Po River Rivers may still bring from the sea to inland Tiber River economic strength to areas, which has a city or society today, economic benefits. since fishing, trade, and Rivers also can be protection are offered by used by the military for water. However, the extent transport during battle to which rivers determine or for supplying armies. economic strength and military protection is lessened by the variety of modern options: e.g., trade by air, the computer industry, and military protection by air. River Valleys River valleys are critical Po River Valley River valleys can still for agriculture because Tiber River Valley increase a society’s they have easy access power due to access to water. They can to water. However, make a society more since water can economically powerful. now be transported long distances, the presence of river valleys does not necessarily determine a society’s strength relative to other societies. © 2015 National Geographic Society NatGeoEd.org 1 Physical Geography and Power in Ancient Rome Answer Key, continued General Feature of How could this type Name the specific Would the same Physical Geography of feature strengthen feature in the Roman feature strengthen an ancient society’s Empire. -

Physical Geography of Southeast Asia

Physical Geography of SE Asia ©2012, TESCCC World Geography Unit 12, Lesson 01 Archipelago • A group of islands. Cordilleras • Parallel mountain ranges and plateaus, that extend into the Indochina Peninsula. Living on the Mainland • Mainland countries include Myanmar, Thailand, Cambodia, Vietnam, and Laos • Laos is a landlocked country • The landscape is characterized by mountains, rivers, river deltas, and plains • The climate includes tropical and mild • The monsoon creates a dry and rainy season ©2012, TESCCC Identify the mainland countries on your map. LAOS VIETNAM MYANMAR THAILAND CAMBODIA Human Settlement on the Mainland • People rely on the rivers that begin in the mountains as a source of water for drinking, transportation, and irrigation • Many people live in small villages • The river deltas create dense population centers • River create rich deposits of sediment that settle along central plains ©2012, TESCCC Major Cities on the Mainland • Myanmar- Yangon (Rangoon), Mandalay • Thailand- Bangkok • Vietnam- Hanoi, Ho Chi Minh City (Saigon) • Cambodia- Phnom Penh ©2012, TESCCC Label the major cities on your map BANGKOK YANGON HO CHI MINH CITY PHNOM PEHN Chao Phraya River • Flows into the Gulf of Thailand, Bangkok is located along the river’s delta Irrawaddy River • Located in Myanmar, Rangoon located along the river Mekong River • Longest river in the region, forms part of the borders of Myanmar, Laos, and Thailand, empties into the South China Sea in Vietnam Label the important rivers and the bodies of water on your map. MEKONG IRRAWADDY CHAO PRAYA ©2012, TESCCC Living on the Islands • The island nations are fragmented • Nations are on islands are made up of island groups. -

295 Emanuela Borgia (Rome) CILICIA and the ROMAN EMPIRE

EMANUELA BORGIA, CILICIA AND THE ROMAN EMPIRE STUDIA EUROPAEA GNESNENSIA 16/2017 ISSN 2082-5951 DOI 10.14746/seg.2017.16.15 Emanuela Borgia (Rome) CILICIA AND THE ROMAN EMPIRE: REFLECTIONS ON PROVINCIA CILICIA AND ITS ROMANISATION Abstract This paper aims at the study of the Roman province of Cilicia, whose formation process was quite long (from the 1st century BC to 72 AD) and complicated by various events. Firstly, it will focus on a more precise determination of the geographic limits of the region, which are not clear and quite ambiguous in the ancient sources. Secondly, the author will thoroughly analyze the formation of the province itself and its progressive Romanization. Finally, political organization of Cilicia within the Roman empire in its different forms throughout time will be taken into account. Key words Cilicia, provincia Cilicia, Roman empire, Romanization, client kings 295 STUDIA EUROPAEA GNESNENSIA 16/2017 · ROME AND THE PROVINCES Quos timuit superat, quos superavit amat (Rut. Nam., De Reditu suo, I, 72) This paper attempts a systematic approach to the study of the Roman province of Cilicia, whose formation process was quite long and characterized by a complicated sequence of historical and political events. The main question is formulated drawing on – though in a different geographic context – the words of G. Alföldy1: can we consider Cilicia a „typical” province of the Roman empire and how can we determine the peculiarities of this province? Moreover, always recalling a point emphasized by G. Alföldy, we have to take into account that, in order to understand the characteristics of a province, it is fundamental to appreciate its level of Romanization and its importance within the empire from the economic, political, military and cultural points of view2. -

Greek-Anatolian Language Contact and the Settlement of Pamphylia

CHRISTINA SKELTON Greek-Anatolian Language Contact and the Settlement of Pamphylia The Ancient Greek dialect of Pamphylia shows extensive influence from the nearby Anatolian languages. Evidence from the linguistics of Greek and Anatolian, sociolinguistics, and the histor- ical and archaeological record suggest that this influence is due to Anatolian speakers learning Greek as a second language as adults in such large numbers that aspects of their L2 Greek became fixed as a part of the main Pamphylian dialect. For this linguistic development to occur and persist, Pamphylia must initially have been settled by a small number of Greeks, and remained isolated from the broader Greek-speaking community while prevailing cultural atti- tudes favored a combined Greek-Anatolian culture. 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 BACKGROUND The Greek-speaking world of the Archaic and Classical periods (ca. ninth through third centuries BC) was covered by a patchwork of different dialects of Ancient Greek, some of them quite different from the Attic and Ionic familiar to Classicists. Even among these varied dialects, the dialect of Pamphylia, located on the southern coast of Asia Minor, stands out as something unusual. For example, consider the following section from the famous Pamphylian inscription from Sillyon: συ Διϝι̣ α̣ ̣ και hιιαροισι Μανεˉ[ς .]υαν̣ hελε ΣελυW[ι]ιυ̣ ς̣ ̣ [..? hι†ια[ρ]α ϝιλ̣ σιι̣ ọς ̣ υπαρ και ανιιας̣ οσα περ(̣ ι)ι[στα]τυ ̣ Wοικ[. .] The author would like to thank Sally Thomason, Craig Melchert, Leonard Neidorf and the anonymous reviewer for their valuable input, as well as Greg Nagy and everyone at the Center for Hellenic Studies for allowing me to use their library and for their wonderful hospitality during the early stages of pre- paring this manuscript. -

A New Geography of European Power?

A NEW GEOGRAPHY OF EUROPEAN POWER? EGMONT PAPER 42 A NEW GEOGRAPHY OF EUROPEAN POWER? James ROGERS January 2011 The Egmont Papers are published by Academia Press for Egmont – The Royal Institute for International Relations. Founded in 1947 by eminent Belgian political leaders, Egmont is an independent think-tank based in Brussels. Its interdisciplinary research is conducted in a spirit of total academic freedom. A platform of quality information, a forum for debate and analysis, a melting pot of ideas in the field of international politics, Egmont’s ambition – through its publications, seminars and recommendations – is to make a useful contribution to the decision- making process. *** President: Viscount Etienne DAVIGNON Director-General: Marc TRENTESEAU Series Editor: Prof. Dr. Sven BISCOP *** Egmont - The Royal Institute for International Relations Address Naamsestraat / Rue de Namur 69, 1000 Brussels, Belgium Phone 00-32-(0)2.223.41.14 Fax 00-32-(0)2.223.41.16 E-mail [email protected] Website: www.egmontinstitute.be © Academia Press Eekhout 2 9000 Gent Tel. 09/233 80 88 Fax 09/233 14 09 [email protected] www.academiapress.be J. Story-Scientia NV Wetenschappelijke Boekhandel Sint-Kwintensberg 87 B-9000 Gent Tel. 09/225 57 57 Fax 09/233 14 09 [email protected] www.story.be All authors write in a personal capacity. Lay-out: proxess.be ISBN 978 90 382 1714 7 D/2011/4804/19 U 1547 NUR1 754 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the permission of the publishers. -

Archaeology and History of Lydia from the Early Lydian Period to Late Antiquity (8Th Century B.C.-6Th Century A.D.)

Dokuz Eylül University – DEU The Research Center for the Archaeology of Western Anatolia – EKVAM Colloquia Anatolica et Aegaea Congressus internationales Smyrnenses IX Archaeology and history of Lydia from the early Lydian period to late antiquity (8th century B.C.-6th century A.D.). An international symposium May 17-18, 2017 / Izmir, Turkey ABSTRACTS Edited by Ergün Laflı Gülseren Kan Şahin Last Update: 21/04/2017. Izmir, May 2017 Websites: https://independent.academia.edu/TheLydiaSymposium https://www.researchgate.net/profile/The_Lydia_Symposium 1 This symposium has been dedicated to Roberto Gusmani (1935-2009) and Peter Herrmann (1927-2002) due to their pioneering works on the archaeology and history of ancient Lydia. Fig. 1: Map of Lydia and neighbouring areas in western Asia Minor (S. Patacı, 2017). 2 Table of contents Ergün Laflı, An introduction to Lydian studies: Editorial remarks to the abstract booklet of the Lydia Symposium....................................................................................................................................................8-9. Nihal Akıllı, Protohistorical excavations at Hastane Höyük in Akhisar………………………………10. Sedat Akkurnaz, New examples of Archaic architectural terracottas from Lydia………………………..11. Gülseren Alkış Yazıcı, Some remarks on the ancient religions of Lydia……………………………….12. Elif Alten, Revolt of Achaeus against Antiochus III the Great and the siege of Sardis, based on classical textual, epigraphic and numismatic evidence………………………………………………………………....13. Gaetano Arena, Heleis: A chief doctor in Roman Lydia…….……………………………………....14. Ilias N. Arnaoutoglou, Κοινὸν, συμβίωσις: Associations in Hellenistic and Roman Lydia……….……..15. Eirini Artemi, The role of Ephesus in the late antiquity from the period of Diocletian to A.D. 449, the “Robber Synod”.……………………………………………………………………….………...16. Natalia S. Astashova, Anatolian pottery from Panticapaeum…………………………………….17-18. Ayşegül Aykurt, Minoan presence in western Anatolia……………………………………………...19. -

Ground-Water Resources of the Bengasi Area, Cyrenaica, United Kingdom of Libya

Ground-Water Resources of the Bengasi Area, Cyrenaica, United Kingdom of Libya GEOLOGICAL SURVEY WATER-SUPPLY PAPER 1757-B Prepared under the auspices of the United States Operations Mission to Libya, the United States Corps of Engineers, and the Government of Libya BBQPERTY OF U.S.GW«r..GlCAL SURVEY JRENTON, NEW JEST.W Ground-Water Resources of the Bengasi Area Cyrenaica, United Kingdom of Libya By W. W. DOYEL and F. J. MAGUIRE CONTRIBUTIONS TO THE HYDROLOGY OF AFRICA AND THE MEDITERRANEAN REGION GEOLOGICAL SURVEY WATER-SUPPLY PAPER 1757-B Prepared under the auspices of the United States Operations Mission to Libya, the United States Corps of Engineers, and the Government of Libya UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1964 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR STEWART L. UDALL, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Thomas B. Nolan, Director For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 CONTENTS Page Abstract _ _______________-__--__-_______--__--_-__---_-------_--- Bl Introduction______-______--__-_-____________--------_-----------__ 1 Location and extent of area-----_______----___--_-------------_- 1 Purpose and scope of investigation---______-_______--__-------__- 3 Acknowledgments __________________________-__--_-----_--_____ 3 Geography___________--_---___-_____---____------------_-___---_- 5 General features.._-_____-___________-_-_____--_-_---------_-_- 5 Topography and drainage_______________________--_-------.-_- 6 Climate.____________________.__----- - 6 Geology____________________-________________________-___----__-__ 8 Ground water____._____________-____-_-______-__-______-_--_--__ 10 Bengasi municipal supply_____________________________________ 12 Other water supplies___________________-______-_-_-___-_--____- 14 Test drilling....______._______._______.___________ 15 Conclusions. -

The Enigmatic Amyntas and His Tomb by Paavo Roos*

Athens Journal of History - Volume 6, Issue 2, April 2020 – Pages 139-156 The Enigmatic Amyntas and His Tomb By Paavo Roos* Among the rock-cut tombs in Fethiye, the ancient Telmessus in western Lycia, there are three with temple façade fronts among numerous of other types. The most famous of them is the one called the Amyntas tomb after the short inscription cut on the left anta. The tomb has been mentioned by several travellers and scholars for centuries but never given a thorough description. Also, the inscription has been mentioned by several persons but has got much less interest than it deserves– although it only consists of the name Amyntas and a patronymic there is a lot to discuss about it. In fact, the defective dealing with the inscription is as enigmatic as the existence of it and its connection with the tomb. Although many questions can easily be posed concerning the tomb the answers to give to them are difficult to find. Introduction Among the many rock-cut tombs in Fethiye (Telmessus) in western Lycia there are three chamber-tombs with temple façades overlooking the town and the harbour (Figure 1). The most famous is the first from the right (Figure 2) which is called the tomb of Amyntas after a short inscription on the left anta.1 Several mysteries are connected with the tomb however, not only with the tomb itself and its owner but also with the handling of it by the scholars and with each others᾽ observations, as we shall see. *Retired Lecturer, Lund University, Sweden. -

The History of Cartography, Volume Six: Cartography in the Twentieth Century

The AAG Review of Books ISSN: (Print) 2325-548X (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rrob20 The History of Cartography, Volume Six: Cartography in the Twentieth Century Jörn Seemann To cite this article: Jörn Seemann (2016) The History of Cartography, Volume Six: Cartography in the Twentieth Century, The AAG Review of Books, 4:3, 159-161, DOI: 10.1080/2325548X.2016.1187504 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/2325548X.2016.1187504 Published online: 07 Jul 2016. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 312 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rrob20 The AAG Review OF BOOKS The History of Cartography, Volume Six: Cartography in the Twentieth Century Mark Monmonier, ed. Chicago, document how all cultures of all his- IL: University of Chicago Press, torical periods represented the world 2015. 1,960 pp., set of 2 using maps” (Woodward 2001, 28). volumes, 805 color plates, What started as a chat on a relaxed 119 halftones, 242 line drawings, walk by these two authors in Devon, England, in May 1977 developed into 61 tables. $500.00 cloth (ISBN a monumental historia cartographica, 978-0-226-53469-5). a cartographic counterpart of Hum- boldt’s Kosmos. The project has not Reviewed by Jörn Seemann, been finished yet, as the volumes on Department of Geography, Ball the eighteenth and nineteenth cen- State University, Muncie, IN. tury are still in preparation, and will probably need a few more years to be published. -

The World's Measure: Caesar's Geographies of Gallia and Britannia in Their Contexts and As Evidence of His World Map

The World's Measure: Caesar's Geographies of Gallia and Britannia in their Contexts and as Evidence of his World Map Christopher B. Krebs American Journal of Philology, Volume 139, Number 1 (Whole Number 553), Spring 2018, pp. 93-122 (Article) Published by Johns Hopkins University Press DOI: https://doi.org/10.1353/ajp.2018.0003 For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/687618 Access provided at 25 Oct 2019 22:25 GMT from Stanford Libraries THE WORLD’S MEASURE: CAESAR’S GEOGRAPHIES OF GALLIA AND BRITANNIA IN THEIR CONTEXTS AND AS EVIDENCE OF HIS WORLD MAP CHRISTOPHER B. KREBS u Abstract: Caesar’s geographies of Gallia and Britannia as set out in the Bellum Gallicum differ in kind, the former being “descriptive” and much indebted to the techniques of Roman land surveying, the latter being “scientific” and informed by the methods of Greek geographers. This difference results from their different contexts: here imperialist, there “cartographic.” The geography of Britannia is ultimately part of Caesar’s (only passingly and late) attested great cartographic endeavor to measure “the world,” the beginning of which coincided with his second British expedition. To Tony Woodman, on the occasion of his retirement as Basil L. Gildersleeve Professor of Classics at the University of Virginia, in gratitude. IN ALEXANDRIA AT DINNER with Cleopatra, Caesar felt the sting of curiosity. He inquired of “the linen-wearing Acoreus” (linigerum . Acorea, Luc. 10.175), a learned priest of Isis, whether he would illuminate him on the lands and peoples, gods and customs of Egypt. Surely, Lucan has him add, there had never been “a visitor more capable of the world” than he (mundique capacior hospes, 10.183). -

Early & Rare World Maps, Atlases & Rare Books

19219a_cover.qxp:Layout 1 5/10/11 12:48 AM Page 1 EARLY & RARE WORLD MAPS, ATLASES & RARE BOOKS Mainly from a Private Collection MARTAYAN LAN CATALOGUE 70 EAST 55TH STREET • NEW YORK, NEW YORK 10022 45 To Order or Inquire: Telephone: 800-423-3741 or 212-308-0018 Fax: 212-308-0074 E-Mail: [email protected] Website: www.martayanlan.com Gallery Hours: Monday through Friday 9:30 to 5:30 Saturday and Evening Hours by Appointment. We welcome any questions you might have regarding items in the catalogue. Please let us know of specific items you are seeking. We are also happy to discuss with you any aspect of map collecting. Robert Augustyn Richard Lan Seyla Martayan James Roy Terms of Sale: All items are sent subject to approval and can be returned for any reason within a week of receipt. All items are original engrav- ings, woodcuts or manuscripts and guaranteed as described. New York State residents add 8.875 % sales tax. Personal checks, Visa, MasterCard, American Express, and wire transfers are accepted. To receive periodic updates of recent acquisitions, please contact us or register on our website. Catalogue 45 Important World Maps, Atlases & Geographic Books Mainly from a Private Collection the heron tower 70 east 55th street new york, new york 10022 Contents Item 1. Isidore of Seville, 1472 p. 4 Item 2. C. Ptolemy, 1478 p. 7 Item 3. Pomponius Mela, 1482 p. 9 Item 4. Mer des hystoires, 1491 p. 11 Item 5. H. Schedel, 1493, Nuremberg Chronicle p. 14 Item 6. Bergomensis, 1502, Supplementum Chronicum p.