Archaeology and History of Lydia from the Early Lydian Period to Late Antiquity (8Th Century B.C.-6Th Century A.D.)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Hellenic Saga Gaia (Earth)

The Hellenic Saga Gaia (Earth) Uranus (Heaven) Oceanus = Tethys Iapetus (Titan) = Clymene Themis Atlas Menoetius Prometheus Epimetheus = Pandora Prometheus • “Prometheus made humans out of earth and water, and he also gave them fire…” (Apollodorus Library 1.7.1) • … “and scatter-brained Epimetheus from the first was a mischief to men who eat bread; for it was he who first took of Zeus the woman, the maiden whom he had formed” (Hesiod Theogony ca. 509) Prometheus and Zeus • Zeus concealed the secret of life • Trick of the meat and fat • Zeus concealed fire • Prometheus stole it and gave it to man • Freidrich H. Fuger, 1751 - 1818 • Zeus ordered the creation of Pandora • Zeus chained Prometheus to a mountain • The accounts here are many and confused Maxfield Parish Prometheus 1919 Prometheus Chained Dirck van Baburen 1594 - 1624 Prometheus Nicolas-Sébastien Adam 1705 - 1778 Frankenstein: The Modern Prometheus • Novel by Mary Shelly • First published in 1818. • The first true Science Fiction novel • Victor Frankenstein is Prometheus • As with the story of Prometheus, the novel asks about cause and effect, and about responsibility. • Is man accountable for his creations? • Is God? • Are there moral, ethical constraints on man’s creative urges? Mary Shelly • “I saw the pale student of unhallowed arts kneeling beside the thing he had put together. I saw the hideous phantasm of a man stretched out, and then, on the working of some powerful engine, show signs of life, and stir with an uneasy, half vital motion. Frightful must it be; for supremely frightful would be the effect of any human endeavour to mock the stupendous mechanism of the Creator of the world” (Introduction to the 1831 edition) Did I request thee, from my clay To mould me man? Did I solicit thee From darkness to promote me? John Milton, Paradise Lost 10. -

Abd-Hadad, Priest-King, Abila, , , , Abydos, , Actium, Battle

INDEX Abd-Hadad, priest-king, Akkaron/Ekron, , Abila, , , , Akko, Ake, , , , Abydos, , see also Ptolemaic-Ake Actium, battle, , Alexander III the Great, Macedonian Adaios, ruler of Kypsela, king, –, , , Adakhalamani, Nubian king, and Syria, –, –, , , , Adulis, , –, Aegean Sea, , , , , , –, and Egypt, , , –, , –, – empire of, , , , , , –, legacy of, – –, –, , , death, burial, – Aemilius Paullus, L., cult of, , , Aeropos, Ptolemaic commander, Alexander IV, , , Alexander I Balas, Seleukid king, Afrin, river, , , –, – Agathokleia, mistress of Ptolemy IV, and eastern policy, , and Demetrios II, Agathokles of Syracuse, , –, and Seventh Syrian War, –, , , Agathokles, son of Lysimachos, – death, , , , Alexander II Zabeinas, , , Agathokles, adviser of Ptolemy IV, –, , , –, Alexander Iannai, Judaean king, Aigai, Macedon, , – Ainos, Thrace, , , , Alexander, son of Krateros, , Aitolian League, Aitolians, , , Alexander, satrap of Persis, , , –, , , – Alexandria-by-Egypt, , , , , , , , , , , , , Aitos, son of Apollonios, , , –, , , Akhaian League, , , , , , , –, , , , , , , , , , , , , , Akhaios, son of Seleukos I, , , –, –, , – , , , , , , –, , , , Akhaios, son of Andromachos, , and Sixth Syrian War, –, adviser of Antiochos III, , – Alexandreia Troas, , conquers Asia Minor, – Alexandros, son of Andromachos, king, –, , , –, , , –, , , Alketas, , , Amanus, mountains, , –, index Amathos, Cyprus, and battle of Andros, , , Amathos, transjordan, , Amestris, wife of Lysimachos, , death, Ammonias, Egypt, -

CILICIA: the FIRST CHRISTIAN CHURCHES in ANATOLIA1 Mark Wilson

CILICIA: THE FIRST CHRISTIAN CHURCHES IN ANATOLIA1 Mark Wilson Summary This article explores the origin of the Christian church in Anatolia. While individual believers undoubtedly entered Anatolia during the 30s after the day of Pentecost (Acts 2:9–10), the book of Acts suggests that it was not until the following decade that the first church was organized. For it was at Antioch, the capital of the Roman province of Syria, that the first Christians appeared (Acts 11:20–26). Yet two obscure references in Acts point to the organization of churches in Cilicia at an earlier date. Among the addressees of the letter drafted by the Jerusalem council were the churches in Cilicia (Acts 15:23). Later Paul visited these same churches at the beginning of his second ministry journey (Acts 15:41). Paul’s relationship to these churches points to this apostle as their founder. Since his home was the Cilician city of Tarsus, to which he returned after his conversion (Gal. 1:21; Acts 9:30), Paul was apparently active in church planting during his so-called ‘silent years’. The core of these churches undoubtedly consisted of Diaspora Jews who, like Paul’s family, lived in the region. Jews from Cilicia were members of a Synagogue of the Freedmen in Jerusalem, to which Paul was associated during his time in Jerusalem (Acts 6:9). Antiochus IV (175–164 BC) hellenized and urbanized Cilicia during his reign; the Romans around 39 BC added Cilicia Pedias to the province of Syria. Four cities along with Tarsus, located along or near the Pilgrim Road that transects Anatolia, constitute the most likely sites for the Cilician churches. -

16 Day Tour of Turkey Embarking on a Mysterious Journey to Turkey by Leaving Melbourne 7 Jan 2017 and Arriving Istanbul 8 Jan 2017

16 Day Tour of Turkey Embarking on a mysterious journey to Turkey by leaving Melbourne 7 Jan 2017 and arriving Istanbul 8 Jan 2017. Welcome to Istanbul, a city with a mysterious past filled with myriad of cultures blended into unmatched splendour. Arrive in Ankara at early morning. Embark into a lifetime adventure. Day 1 : (Sun) 8 Jan 2017 Istanbul - Gallipoli - Cannakale Transfer to the Gallipoli Peninsula. Visit Anzac Cove and the poignant Lone Pine Cemetery, the Dardanelles and Ferry crossings from Eceabat to Canakkale. Dinner and Overnight Cannakale (D) Day 2 : (Mon) 9 Jan 2017 Troy – Assos – Pergamum – Izmir Breakfast at hotel. Check out. Today we begin our tour to the legendary city of Troy to see the replica of the wooden horse. We visit the ruins, which sparked our interest as we entered Assos (Acts 20:13-14) where Paul boarded to sail to Mitylene—the relatively intact city walls, the lookout tower, theater and agora. The Byzantine church turned mosque is no longer used. From the top of the volcanic hill we have a spectacular view (if it is clear) of Mitylene located on the sea twelve kilometers away. Then we travel to Pergamon to visit the Acropolis, Temple of Athena, Serapis Temple, Heroon, Sanctuary of Athena, Library of Pergamon, Temple of Tragan, Theatre, Zeus Altar, Kizil Avlu. Our sites today are Pergamum (Church of Pergamum 3) and the small ruins at Thyatira. Pergamum, perched on the hilltop above the modern city of Bergama, is one of the most dramatic sites in Turkey. Strolling through the significant unearthed remnants of marble temples, one Page 1 of 6 wonders at the “technology” which made the construction possible. -

Hadrian and the Greek East

HADRIAN AND THE GREEK EAST: IMPERIAL POLICY AND COMMUNICATION DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By Demetrios Kritsotakis, B.A, M.A. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2008 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Fritz Graf, Adviser Professor Tom Hawkins ____________________________ Professor Anthony Kaldellis Adviser Greek and Latin Graduate Program Copyright by Demetrios Kritsotakis 2008 ABSTRACT The Roman Emperor Hadrian pursued a policy of unification of the vast Empire. After his accession, he abandoned the expansionist policy of his predecessor Trajan and focused on securing the frontiers of the empire and on maintaining its stability. Of the utmost importance was the further integration and participation in his program of the peoples of the Greek East, especially of the Greek mainland and Asia Minor. Hadrian now invited them to become active members of the empire. By his lengthy travels and benefactions to the people of the region and by the creation of the Panhellenion, Hadrian attempted to create a second center of the Empire. Rome, in the West, was the first center; now a second one, in the East, would draw together the Greek people on both sides of the Aegean Sea. Thus he could accelerate the unification of the empire by focusing on its two most important elements, Romans and Greeks. Hadrian channeled his intentions in a number of ways, including the use of specific iconographical types on the coinage of his reign and religious language and themes in his interactions with the Greeks. In both cases it becomes evident that the Greeks not only understood his messages, but they also reacted in a positive way. -

VU Research Portal

VU Research Portal The impact of empire on market prices in Babylon Pirngruber, R. 2012 document version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication in VU Research Portal citation for published version (APA) Pirngruber, R. (2012). The impact of empire on market prices in Babylon: in the Late Achaemenid and Seleucid periods, ca. 400 - 140 B.C. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. E-mail address: [email protected] Download date: 25. Sep. 2021 THE IMPACT OF EMPIRE ON MARKET PRICES IN BABYLON in the Late Achaemenid and Seleucid periods, ca. 400 – 140 B.C. R. Pirngruber VRIJE UNIVERSITEIT THE IMPACT OF EMPIRE ON MARKET PRICES IN BABYLON in the Late Achaemenid and Seleucid periods, ca. 400 – 140 B.C. ACADEMISCH PROEFSCHRIFT ter verkrijging van de graad Doctor aan de Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, op gezag van de rector magnificus prof.dr. -

Republic of Iraq

Republic of Iraq Babylon Nomination Dossier for Inscription of the Property on the World Heritage List January 2018 stnel oC fobalbaT Executive Summary .......................................................................................................................... 1 State Party .......................................................................................................................................................... 1 Province ............................................................................................................................................................. 1 Name of property ............................................................................................................................................... 1 Geographical coordinates to the nearest second ................................................................................................. 1 Center ................................................................................................................................................................ 1 N 32° 32’ 31.09”, E 44° 25’ 15.00” ..................................................................................................................... 1 Textural description of the boundary .................................................................................................................. 1 Criteria under which the property is nominated .................................................................................................. 4 Draft statement -

Female Property Ownership and Status in Classical and Hellenistic Sparta

Female Property Ownership and Status in Classical and Hellenistic Sparta Stephen Hodkinson University of Manchester 1. Introduction The image of the liberated Spartiate woman, exempt from (at least some of) the social and behavioral controls which circumscribed the lives of her counterparts in other Greek poleis, has excited or horrified the imagination of commentators both ancient and modern.1 This image of liberation has sometimes carried with it the idea that women in Sparta exercised an unaccustomed influence over both domestic and political affairs.2 The source of that influence is ascribed by certain ancient writers, such as Euripides (Andromache 147-53, 211) and Aristotle (Politics 1269b12-1270a34), to female control over significant amounts of property. The male-centered perspectives of ancient writers, along with the well-known phenomenon of the “Spartan mirage” (the compound of distorted reality and sheer imaginative fiction regarding the character of Spartan society which is reflected in our overwhelmingly non-Spartan sources) mean that we must treat ancient images of women with caution. Nevertheless, ancient perceptions of their position as significant holders of property have been affirmed in recent modern studies.3 The issue at the heart of my paper is to what extent female property-holding really did translate into enhanced status and influence. In Sections 2-4 of this paper I shall approach this question from three main angles. What was the status of female possession of property, and what power did women have directly to manage and make use of their property? What impact did actual or potential ownership of property by Spartiate women have upon their status and influence? And what role did female property-ownership and status, as a collective phenomenon, play within the crisis of Spartiate society? First, however, in view of the inter-disciplinary audience of this volume, it is necessary to a give a brief outline of the historical context of my discussion. -

The Satrap of Western Anatolia and the Greeks

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2017 The aS trap Of Western Anatolia And The Greeks Eyal Meyer University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons Recommended Citation Meyer, Eyal, "The aS trap Of Western Anatolia And The Greeks" (2017). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 2473. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2473 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2473 For more information, please contact [email protected]. The aS trap Of Western Anatolia And The Greeks Abstract This dissertation explores the extent to which Persian policies in the western satrapies originated from the provincial capitals in the Anatolian periphery rather than from the royal centers in the Persian heartland in the fifth ec ntury BC. I begin by establishing that the Persian administrative apparatus was a product of a grand reform initiated by Darius I, which was aimed at producing a more uniform and centralized administrative infrastructure. In the following chapter I show that the provincial administration was embedded with chancellors, scribes, secretaries and military personnel of royal status and that the satrapies were periodically inspected by the Persian King or his loyal agents, which allowed to central authorities to monitory the provinces. In chapter three I delineate the extent of satrapal authority, responsibility and resources, and conclude that the satraps were supplied with considerable resources which enabled to fulfill the duties of their office. After the power dynamic between the Great Persian King and his provincial governors and the nature of the office of satrap has been analyzed, I begin a diachronic scrutiny of Greco-Persian interactions in the fifth century BC. -

Keltoi and Hellenes: a Study of the Celts in the Hellenistic World

KELTOI AND THE HELLENES A STUDY OF THE CELTS IN THE HELLENISTIC WoRU) PATRICK EGAN In the third century B.C. a large body ofCeltic tribes thrust themselves violently into the turbulent world of the Diadochoi,’ immediately instilling fear, engendering anger and finally, commanding respect from the peoples with whom they came into contact. Their warlike nature, extreme hubris and vigorous energy resembled Greece’s own Homeric past, but represented a culture, language and way of life totally alien to that of the Greeks and Macedonians in this period. In the years that followed, the Celts would go on to ravage Macedonia, sack Delphi, settle their own “kingdom” and ifil the ranks of the Successors’ armies. They would leave indelible marks on the Hellenistic World, first as plundering barbaroi and finally, as adapted, integral elements and members ofthe greatermulti-ethnic society that was taking shape around them. This paper will explore the roles played by the Celts by examining their infamous incursions into Macedonia and Greece, their phase of settlement and occupation ofwhat was to be called Galatia, their role as mercenaries, and finally their transition and adaptation, most noticeably on the individual level, to the demands of the world around them. This paper will also seek to challenge some of the traditionally hostile views held by Greek historians regarding the role, achievements, and the place the Celts occupied as members, not simply predators, of the Hellenistic World.2 19 THE DAWN OF THE CELTS IN THE HELLENISTIC WORLD The Celts were not unknown to all Greeks in the years preceding the Deiphic incursion of February, 279. -

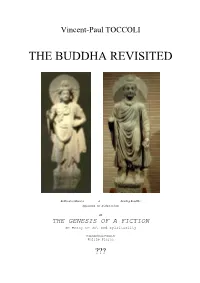

The Buddha Revisited

Vincent-Paul TOCCOLI THE BUDDHA REVISITED Bodhisattva Maitreya & Standing Bouddha Afghanistan, 1er & 2ème sicècles or THE GENESIS OF A FICTION an essay on art and spirituality Translated from French by Philip Pierce ??? "Stories do not belong to eternity "They belong to time "And out of time they grow... "It is in time "That stories, relived and redreamed "Become timeless... "Nations and people are largely the stories they feed themselves "If they tell themselves stories that are lies, "They will suffer the future consequences of those lies. "If they tell themselves stories that free their own truths "They will free their histories forfuture flowerings. (Ben OKRI, Birds of heaven, 25, 15) "Dans leur prétention à la sagesse, "Ils sont devenus fous, "Et ils ont changé la gloire du dieu incorruptible "Contre une représentation, "Simple image d`homme corruptible. (St Paul, to the Romans, 1, 22-23) C O N T E N T S INTRODUCTION FIRST PART: THE MAKING-SENSE TRANSGRESSIONS 1st SECTION: ON THE GANGES SIDE, 5th-1st cent. BC. Chap.1: The Buddhism of the Buddha Chap.2: The state of Buddhism under the last Mauryas 2nd SECTION: ON THE INDUS SIDE, 4th-1st cent. BC. Chap.3: The permanence of Philhellenism, from the Graeco-bactrians to the Scytho-Parthans Chap.4: An approach to the graeco-hellenistic influence SECOND PART: THE ARTIFICIAL FECUNDATIONS 3rd SECTION: THE SYMBOLIC IMAGINARY AND THE REPRESENTATION OF THE SACRED Chap.5: The figurative vision of Buddhism Chap.6: The aesthetic tradition of Greek sculpture 4th SECTION: THE PRECIPITATE IN SPACE -

The Cambridge Companion to Greek Mythology (2007)

P1: JzG 9780521845205pre CUFX147/Woodard 978 0521845205 Printer: cupusbw July 28, 2007 1:25 The Cambridge Companion to GREEK MYTHOLOGY S The Cambridge Companion to Greek Mythology presents a comprehensive and integrated treatment of ancient Greek mythic tradition. Divided into three sections, the work consists of sixteen original articles authored by an ensemble of some of the world’s most distinguished scholars of classical mythology. Part I provides readers with an examination of the forms and uses of myth in Greek oral and written literature from the epic poetry of the eighth century BC to the mythographic catalogs of the early centuries AD. Part II looks at the relationship between myth, religion, art, and politics among the Greeks and at the Roman appropriation of Greek mythic tradition. The reception of Greek myth from the Middle Ages to modernity, in literature, feminist scholarship, and cinema, rounds out the work in Part III. The Cambridge Companion to Greek Mythology is a unique resource that will be of interest and value not only to undergraduate and graduate students and professional scholars, but also to anyone interested in the myths of the ancient Greeks and their impact on western tradition. Roger D. Woodard is the Andrew V.V.Raymond Professor of the Clas- sics and Professor of Linguistics at the University of Buffalo (The State University of New York).He has taught in the United States and Europe and is the author of a number of books on myth and ancient civiliza- tion, most recently Indo-European Sacred Space: Vedic and Roman Cult. Dr.