The World's Measure: Caesar's Geographies of Gallia and Britannia in Their Contexts and As Evidence of His World Map

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TITLE: Pomponius Mela's World Map DATE: A.D. 37 AUTHOR: Pomponius Mela

Pomponius Mela’s World View #116 TITLE: Pomponius Mela’s World Map DATE: A.D. 37 AUTHOR: Pomponius Mela DESCRIPTION: The images in this monograph show attempts at reconstruction of the world view of the earliest Roman geographer Pomponius Mela, who, although of Spanish birth, wrote a brief work which agrees in most of its views with the great Greek writers from Eratosthenes (#112) to Strabo (#115). However, Mela departs from the traditional ancient concept by asserting that in the southern temperate zone dwelt inhabitants who were inaccessible to Europeans because of the Torrid Zone that intervened. His knowledge of the characters of Western Europe and the British Isles was clearer than that of the Greek writers, and he was the first to name the Orcades [Orkney Islands]. The great Roman historian Pliny quoted Mela as an authority. The first-century author Pomponius Mela enjoyed a long- standing reputation in geographical matters, given Pliny’s praise of him in the Natural History. But no text by Mela was known until the 1330s, when Petrarch discovered his De chorographia [On Chorography, or Descriptive Geography] in Avignon. Mela did not include a map in his text, but it has been suggested that he had in mind the map of the known world that Agrippa (#118) had started and Augustus completed. Displayed in the Porticus Vipsania in Rome, this map was known as chorographia, a name possibly recalled by the title of Mela’s text. Petrarch was fascinated with Mela’s brief and engaging text and had copies made for fellow humanists, including Giovanni Boccaccio, facilitating the wide circulation of the manuscript for almost a century, until it was printed in Milan in 1471. -

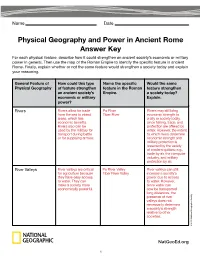

Physical Geography and Power in Ancient Rome Answer

Name Date Physical Geography and Power in Ancient Rome Answer Key For each physical feature, describe how it could strengthen an ancient society’s economic or military power in general. Then use the map of the Roman Empire to identify the specific feature in ancient Rome. Finally, explain whether or not the same feature would strengthen a society today and explain your reasoning. General Feature of How could this type Name the specific Would the same Physical Geography of feature strengthen feature in the Roman feature strengthen an ancient society’s Empire. a society today? economic or military Explain. power? Rivers Rivers allow for trade Po River Rivers may still bring from the sea to inland Tiber River economic strength to areas, which has a city or society today, economic benefits. since fishing, trade, and Rivers also can be protection are offered by used by the military for water. However, the extent transport during battle to which rivers determine or for supplying armies. economic strength and military protection is lessened by the variety of modern options: e.g., trade by air, the computer industry, and military protection by air. River Valleys River valleys are critical Po River Valley River valleys can still for agriculture because Tiber River Valley increase a society’s they have easy access power due to access to water. They can to water. However, make a society more since water can economically powerful. now be transported long distances, the presence of river valleys does not necessarily determine a society’s strength relative to other societies. © 2015 National Geographic Society NatGeoEd.org 1 Physical Geography and Power in Ancient Rome Answer Key, continued General Feature of How could this type Name the specific Would the same Physical Geography of feature strengthen feature in the Roman feature strengthen an ancient society’s Empire. -

Language Contact and Identity in Roman Britain

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 5-16-2016 12:00 AM Language Contact and Identity in Roman Britain Robert Jackson Woodcock The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Professor Alexander Meyer The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Classics A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Master of Arts © Robert Jackson Woodcock 2016 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons, and the Indo- European Linguistics and Philology Commons Recommended Citation Woodcock, Robert Jackson, "Language Contact and Identity in Roman Britain" (2016). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 3775. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/3775 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract Language is one of the most significant aspects of cultural identity. This thesis examines the evidence of languages in contact in Roman Britain in order to determine the role that language played in defining the identities of the inhabitants of this Roman province. All forms of documentary evidence from monumental stone epigraphy to ownership marks scratched onto pottery are analyzed for indications of bilingualism and language contact in Roman Britain. The language and subject matter of the Vindolanda writing tablets from a Roman army fort on the northern frontier are analyzed for indications of bilingual interactions between Roman soldiers and their native surroundings, as well as Celtic interference on the Latin that was written and spoken by the Roman army. -

1 Gallo-Roman Relations Under the Early Empire by Ryan Walsh A

Gallo-Roman Relations under the Early Empire By Ryan Walsh A thesis presented to the University of Waterloo in fulfillment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Master of Arts in Ancient Mediterranean Cultures Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, 2013 © Ryan Walsh 2013 1 Author's Declaration I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. ii Abstract This paper examines the changing attitudes of Gallo-Romans from the time of Caesar's conquest in the 50s BCE to the start of Vespasian's reign in 70-71 CE and how Roman prejudice shaped those attitudes. I first examine the conflicted opinions of the Gauls in Caesar's time and how they eventually banded together against him but were defeated. Next, the activities of each Julio-Claudian emperor are examined to see how they impacted Gaul and what the Gallo-Roman response was. Throughout this period there is clear evidence of increased Romanisation amongst the Gauls and the prominence of the region is obvious in imperial policy. This changes with Nero's reign where Vindex's rebellion against the emperor highlights the prejudices still effecting Roman attitudes. This only becomes worse in the rebellion of Civilis the next year. After these revolts, the Gallo-Romans appear to retreat from imperial offices and stick to local affairs, likely as a direct response to Rome's rejection of them. -

The Architecture of Marcus Vitruvius Pollio, in Ten Books

www.e-rara.ch The architecture of Marcus Vitruvius Pollio, in ten books Vitruvius London, 1826 Bibliothek Werner Oechslin Shelf Mark: A04a ; app. 851 Persistent Link: http://dx.doi.org/10.3931/e-rara-19442 Life of Vitruvius. www.e-rara.ch Die Plattform e-rara.ch macht die in Schweizer Bibliotheken vorhandenen Drucke online verfügbar. Das Spektrum reicht von Büchern über Karten bis zu illustrierten Materialien – von den Anfängen des Buchdrucks bis ins 20. Jahrhundert. e-rara.ch provides online access to rare books available in Swiss libraries. The holdings extend from books and maps to illustrated material – from the beginnings of printing to the 20th century. e-rara.ch met en ligne des reproductions numériques d’imprimés conservés dans les bibliothèques de Suisse. L’éventail va des livres aux documents iconographiques en passant par les cartes – des débuts de l’imprimerie jusqu’au 20e siècle. e-rara.ch mette a disposizione in rete le edizioni antiche conservate nelle biblioteche svizzere. La collezione comprende libri, carte geografiche e materiale illustrato che risalgono agli inizi della tipografia fino ad arrivare al XX secolo. Nutzungsbedingungen Dieses Digitalisat kann kostenfrei heruntergeladen werden. Die Lizenzierungsart und die Nutzungsbedingungen sind individuell zu jedem Dokument in den Titelinformationen angegeben. Für weitere Informationen siehe auch [Link] Terms of Use This digital copy can be downloaded free of charge. The type of licensing and the terms of use are indicated in the title information for each document individually. For further information please refer to the terms of use on [Link] Conditions d'utilisation Ce document numérique peut être téléchargé gratuitement. -

Physical Geography of Southeast Asia

Physical Geography of SE Asia ©2012, TESCCC World Geography Unit 12, Lesson 01 Archipelago • A group of islands. Cordilleras • Parallel mountain ranges and plateaus, that extend into the Indochina Peninsula. Living on the Mainland • Mainland countries include Myanmar, Thailand, Cambodia, Vietnam, and Laos • Laos is a landlocked country • The landscape is characterized by mountains, rivers, river deltas, and plains • The climate includes tropical and mild • The monsoon creates a dry and rainy season ©2012, TESCCC Identify the mainland countries on your map. LAOS VIETNAM MYANMAR THAILAND CAMBODIA Human Settlement on the Mainland • People rely on the rivers that begin in the mountains as a source of water for drinking, transportation, and irrigation • Many people live in small villages • The river deltas create dense population centers • River create rich deposits of sediment that settle along central plains ©2012, TESCCC Major Cities on the Mainland • Myanmar- Yangon (Rangoon), Mandalay • Thailand- Bangkok • Vietnam- Hanoi, Ho Chi Minh City (Saigon) • Cambodia- Phnom Penh ©2012, TESCCC Label the major cities on your map BANGKOK YANGON HO CHI MINH CITY PHNOM PEHN Chao Phraya River • Flows into the Gulf of Thailand, Bangkok is located along the river’s delta Irrawaddy River • Located in Myanmar, Rangoon located along the river Mekong River • Longest river in the region, forms part of the borders of Myanmar, Laos, and Thailand, empties into the South China Sea in Vietnam Label the important rivers and the bodies of water on your map. MEKONG IRRAWADDY CHAO PRAYA ©2012, TESCCC Living on the Islands • The island nations are fragmented • Nations are on islands are made up of island groups. -

Grade 10 Literature Mini-Assessment Excerpt from Julius Caesar, Act III, Scene Ii

Grade 10 Literature Mini-Assessment Excerpt from Julius Caesar, Act III, Scene ii by William Shakespeare This grade 10 mini-assessment is based on an excerpt from Julius Caesar, Act III, Scene ii by William Shakespeare and a video of the scene. This text is considered to be worthy of students’ time to read and also meets the expectations for text complexity at grade 10. Assessments aligned to the Common Core State Standards (CCSS) will employ quality, complex texts such as this one. Questions aligned to the CCSS should be worthy of students’ time to answer and therefore do not focus on minor points of the text. Questions also may address several standards within the same question because complex texts tend to yield rich assessment questions that call for deep analysis. In this mini- assessment there are seven selected-response questions and one paper/pencil equivalent of technology enhanced items that address the Reading Standards listed below. Additionally, there is an optional writing prompt, which is aligned to both the Reading Standards for Literature and the Writing Standards. We encourage educators to give students the time that they need to read closely and write to the source. While we know that it is helpful to have students complete the mini-assessment in one class period, we encourage educators to allow additional time as necessary. Note for teachers of English Language Learners (ELLs): This assessment is designed to measure students’ ability to read and write in English. Therefore, educators will not see the level of scaffolding typically used in instructional materials to support ELLs—these would interfere with the ability to understand their mastery of these skills. -

Greek-Anatolian Language Contact and the Settlement of Pamphylia

CHRISTINA SKELTON Greek-Anatolian Language Contact and the Settlement of Pamphylia The Ancient Greek dialect of Pamphylia shows extensive influence from the nearby Anatolian languages. Evidence from the linguistics of Greek and Anatolian, sociolinguistics, and the histor- ical and archaeological record suggest that this influence is due to Anatolian speakers learning Greek as a second language as adults in such large numbers that aspects of their L2 Greek became fixed as a part of the main Pamphylian dialect. For this linguistic development to occur and persist, Pamphylia must initially have been settled by a small number of Greeks, and remained isolated from the broader Greek-speaking community while prevailing cultural atti- tudes favored a combined Greek-Anatolian culture. 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 BACKGROUND The Greek-speaking world of the Archaic and Classical periods (ca. ninth through third centuries BC) was covered by a patchwork of different dialects of Ancient Greek, some of them quite different from the Attic and Ionic familiar to Classicists. Even among these varied dialects, the dialect of Pamphylia, located on the southern coast of Asia Minor, stands out as something unusual. For example, consider the following section from the famous Pamphylian inscription from Sillyon: συ Διϝι̣ α̣ ̣ και hιιαροισι Μανεˉ[ς .]υαν̣ hελε ΣελυW[ι]ιυ̣ ς̣ ̣ [..? hι†ια[ρ]α ϝιλ̣ σιι̣ ọς ̣ υπαρ και ανιιας̣ οσα περ(̣ ι)ι[στα]τυ ̣ Wοικ[. .] The author would like to thank Sally Thomason, Craig Melchert, Leonard Neidorf and the anonymous reviewer for their valuable input, as well as Greg Nagy and everyone at the Center for Hellenic Studies for allowing me to use their library and for their wonderful hospitality during the early stages of pre- paring this manuscript. -

The Basques of Lapurdi, Zuberoa, and Lower Navarre Their History and Their Traditions

Center for Basque Studies Basque Classics Series, No. 6 The Basques of Lapurdi, Zuberoa, and Lower Navarre Their History and Their Traditions by Philippe Veyrin Translated by Andrew Brown Center for Basque Studies University of Nevada, Reno Reno, Nevada This book was published with generous financial support obtained by the Association of Friends of the Center for Basque Studies from the Provincial Government of Bizkaia. Basque Classics Series, No. 6 Series Editors: William A. Douglass, Gregorio Monreal, and Pello Salaburu Center for Basque Studies University of Nevada, Reno Reno, Nevada 89557 http://basque.unr.edu Copyright © 2011 by the Center for Basque Studies All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America Cover and series design © 2011 by Jose Luis Agote Cover illustration: Xiberoko maskaradak (Maskaradak of Zuberoa), drawing by Paul-Adolph Kaufman, 1906 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Veyrin, Philippe, 1900-1962. [Basques de Labourd, de Soule et de Basse Navarre. English] The Basques of Lapurdi, Zuberoa, and Lower Navarre : their history and their traditions / by Philippe Veyrin ; with an introduction by Sandra Ott ; translated by Andrew Brown. p. cm. Translation of: Les Basques, de Labourd, de Soule et de Basse Navarre Includes bibliographical references and index. Summary: “Classic book on the Basques of Iparralde (French Basque Country) originally published in 1942, treating Basque history and culture in the region”--Provided by publisher. ISBN 978-1-877802-99-7 (hardcover) 1. Pays Basque (France)--Description and travel. 2. Pays Basque (France)-- History. I. Title. DC611.B313V513 2011 944’.716--dc22 2011001810 Contents List of Illustrations..................................................... vii Note on Basque Orthography......................................... -

Two Studies on Roman London. Part B: Population Decline and Ritual Landscapes in Antonine London

Two Studies on Roman London. Part B: population decline and ritual landscapes in Antonine London In this paper I turn my attention to the changes that took place in London in the mid to late second century. Until recently the prevailing orthodoxy amongst students of Roman London was that the settlement suffered a major population decline in this period. Recent excavations have shown that not all properties were blighted by abandonment or neglect, and this has encouraged some to suggest that the evidence for decline may have been exaggerated.1 Here I wish to restate the case for a significant decline in housing density in the period circa AD 160, but also draw attention to evidence for this being a period of increased investment in the architecture of religion and ceremony. New discoveries of temple complexes have considerably improved our ability to describe London’s evolving ritual landscape. This evidence allows for the speculative reconstruction of the main processional routes through the city. It also shows that the main investment in ceremonial architecture took place at the very time that London’s population was entering a period of rapid decline. We are therefore faced with two puzzling developments: why were parts of London emptied of houses in the middle second century, and why was this contraction accompanied by increased spending on religious architecture? This apparent contradiction merits detailed consideration. The causes of the changes of this period have been much debated, with most emphasis given to the economic and political factors that reduced London’s importance in late antiquity. These arguments remain valid, but here I wish to return to the suggestion that the Antonine plague, also known as the plague of Galen, may have been instrumental in setting London on its new trajectory.2 The possible demographic and economic consequences of this plague have been much debated in the pages of this journal, with a conservative view of its impact generally prevailing. -

1996 Njcl Certamen Round A1 (Revised)

1996 NJCL CERTAMEN ROUND A1 (REVISED) 1. Who immortalized the wife of Quintus Caecilius Metellus as Lesbia in his poetry? (GAIUS VALERIUS) CATULLUS What was probably the real name of Lesbia? CLODIA What orator fiercely attacked Clodia in his Pro Caelio? (MARCUS TULLIUS) CICERO 2. According to Hesiod, who was the first born of Cronus and Rhea? HESTIA Who was the second born? DEMETER Who was the fifth born? POSEIDON 3. Name the twin brothers who fought in their mother's womb. PROETUS & ACRISIUS Whom did Proetus marry? ANTIA (ANTEIA) (STHENEBOEA) With what hero did Antia fall in love? BELLEROPHON 4. Give the comparative and superlative forms of mult§ PLâRS, PLâRIM¦ ...of prÇ. PRIOR, PR¦MUS ...of hebes. HEBETIOR, HEBETISSIMUS 5. LegÇ means “I collect.” What does lectitÇ mean? (I) COLLECT OFTEN, EAGERLY Sitis means “thirst.” What does the verb sitiÇ mean? (I) AM THIRSTY / THIRST CantÇ means “I sing.” What does cantillÇ mean? (I) CHIRP, WARBLE, HUM, SING LOW 6. Differentiate in meaning between p~vÇ and paveÇ. P}VÆ -- PEACOCK PAVEÆ -- (I) FEAR, TREMBLE Differentiate in meaning between cavÇ and caveÇ. CAVÆ -- I HOLLOW OUT CAVEÆ -- I TAKE HEED, BEWARE Differentiate in meaning between modo (must pronounce with short “o”) and madeÇ. MODO -- ONLY, MERELY, BUT, JUST, IMMEDIATELY, PROVIDED THAT MADEÆ -- I AM WET, DRUNK Page 1 -- A1 7. What two words combine to form the Latin verb malÇ? MAGIS & VOLÆ What does malÇ mean? PREFER M~la is a contracted form of maxilla. What is a m~la? CHEEK, JAW 8. Which of the emperors of AD 193 executed the assassins of Commodus? DIDIUS JULIANUS How had Julianus gained imperial power? BOUGHT THE THRONE AT AN AUCTION (HELD BY THE PRAETORIANS) Whom had the Praetorians murdered after his reign of 87 days? PERTINAX 9. -

ROMANIZATION and SOME CILICIAN CULTS by HUGH ELTON (BIAA)

ROMANIZATION AND SOME CILICIAN CULTS By HUGH ELTON (BIAA) This paper focuses on two sites from central Cilicia in Anatolia, the Cory cian Cave and Kanhdivane, to make some comments about religion and Romanization. From the Corycian Cave, a pair of early third-century AD altars are dedicated to Zeus Korykios, described as Victorious (Epinikios), Triumphant (Tropaiuchos), and the Harvester (Epikarpios), and to Hermes Korykios, also Victorious, Triumphant, and the Harvester. The altars were erected for 'the fruitfulness and brotherly love of the Augusti', suggesting they come from the period before Geta's murder, i.e. between AD 209 and 212. 1 These altars are unremarkable and similar examples are common else where, so these altars can be interpreted as showing the homogenising effect of the Roman Empire. But behind these dedications, however, may lie a re ligious tradition stretching back to the second millennium BC. At the second site, Kanhdivane, a tomb in the west necropolis was accompanied by a fu nerary inscription erected by Marcus Ulpius Knos for himself and his family, probably in the second century AD. Marcus then added, 'but if anyone damages or opens [the tomb] let him pay to the treasury of Zeus 1000 [de narii] and to the Moon (Selene) and to the Sun (Helios) above 1000 [denarii] and let him be subject to the curses also of the Underground Gods (Kata chthoniai Theoi). ' 2 When he wanted to threaten retribution, Knos turned to a local group of gods. As at the Corycian Cave, Knos' actions may preserve traces of pre-Roman practices, though within a Roman framework.