Geographic Board Games

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

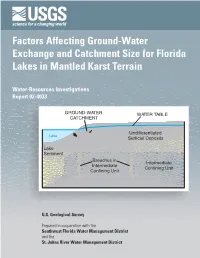

Factors Affecting Ground-Water Exchange and Catchment Size for Florida Lakes in Mantled Karst Terrain

Factors Affecting Ground-Water Exchange and Catchment Size for Florida Lakes in Mantled Karst Terrain Water-Resources Investigations Report 02-4033 GROUND-WATER WATER TABLE CATCHMENT Undifferentiated Lake Surficial Deposits Lake Sediment Breaches in Intermediate Intermediate Confining Unit Confining Unit U.S. Geological Survey Prepared in cooperation with the Southwest Florida Water Management District and the St. Johns River Water Management District Factors Affecting Ground-Water Exchange and Catchment Size for Florida Lakes in Mantled Karst Terrain By T.M. Lee U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Water-Resources Investigations Report 02-4033 Prepared in cooperation with the SOUTHWEST FLORIDA WATER MANAGEMENT DISTRICT and the ST. JOHNS RIVER WATER MANAGEMENT DISTRICT Tallahassee, Florida 2002 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR GALE A. NORTON, Secretary U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY CHARLES G. GROAT, Director The use of firm, trade, and brand names in this report is for identification purposes only and does not constitute endorsement by the U.S. Geological Survey. For additional information Copies of this report can be write to: purchased from: District Chief U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Geological Survey Branch of Information Services Suite 3015 Box 25286 227 N. Bronough Street Denver, CO 80225-0286 Tallahassee, FL 32301 888-ASK-USGS Additional information about water resources in Florida is available on the World Wide Web at http://fl.water.usgs.gov CONTENTS Abstract................................................................................................................................................................................. -

Vertical Motions of Australia During the Cretaceous

Basin Research (1994) 6,63-76 The planform of epeirogeny: vertical motions of Australia during the Cretaceous Mark Russell and Michael Gurnis* Department of Geological Sciences, The University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI 48109-1063,USA ABSTRACT Estimates of dynamic motion of Australia since the end of the Jurassic have been made by modelling marine flooding and comparing it with palaeogeographical reconstructions of marine inundation. First, sediment isopachs were backstripped from present-day topography. Dynamic motion was determined by the displacement needed to approximate observed flooding when allowance is made for changes in eustatic sea-level. The reconstructed inundation patterns suggest that during the Cretaceous, Australia remained a relatively stable platform, and flooding in the eastern interior during the Early Cretaceous was primarily the result of the regional tectonic motion. Vertical motion during the Cretaceous was much smaller than the movement since the end of the Cretaceous. Subsidence and marine flooding in the Eromanga and Surat Basins, and the subsequent 500 m of uplift of the eastern portion of the basin, may have been driven by changes in plate dynamics during the Mesozoic. Convergence along the north-east edge of Australia between 200 and 100 Ma coincides with platform sedimentation and subsidence within the Eromanga and Surat Basins. A major shift in the position of subduction at 140Ma was coeval with the marine incursion into the Eromanga. When subduction ended at 95 Ma, marine inundation of the Eromanga also ended. Subsidence and uplift of the eastern interior is consistent with dynamic models of subduction in which subsidence is generated when the dip angle of the slab decreases and uplift is generated when subduction terminates (i.e. -

Water Flow in the Silurian-Devonian Aquifer System, Johnson County, Iowa

Hydrogeology and Simulation of Ground- Water Flow in the Silurian-Devonian Aquifer System, Johnson County, Iowa By Patrick Tucci (U.S. Geological Survey) and Robert M. McKay (Iowa Department of Natural Resources, Iowa Geological Survey) Prepared in cooperation with The Iowa Department of Natural Resources – Water Supply Bureau City of Iowa City Johnson County Board of Supervisors City of Coralville The University of Iowa City of North Liberty City of Solon Scientific Investigations Report 2005–5266 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior Gale A. Norton, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey P. Patrick Leahy, Acting Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2006 For product and ordering information: World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS For more information on the USGS--the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment: World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this report is in the public domain, permission must be secured from the individual copyright owners to reproduce any copyrighted materials contained within this report. Suggested citation: Tucci, Patrick and McKay, Robert, 2006, Hydrogeology and simulation of ground-water flow in the Silurian-Devonian aquifer system, Johnson County, Iowa: U.S. Geological Survey, Scientific Investigations -

The History of Cartography, Volume 3

THE HISTORY OF CARTOGRAPHY VOLUME THREE Volume Three Editorial Advisors Denis E. Cosgrove Richard Helgerson Catherine Delano-Smith Christian Jacob Felipe Fernández-Armesto Richard L. Kagan Paula Findlen Martin Kemp Patrick Gautier Dalché Chandra Mukerji Anthony Grafton Günter Schilder Stephen Greenblatt Sarah Tyacke Glyndwr Williams The History of Cartography J. B. Harley and David Woodward, Founding Editors 1 Cartography in Prehistoric, Ancient, and Medieval Europe and the Mediterranean 2.1 Cartography in the Traditional Islamic and South Asian Societies 2.2 Cartography in the Traditional East and Southeast Asian Societies 2.3 Cartography in the Traditional African, American, Arctic, Australian, and Pacific Societies 3 Cartography in the European Renaissance 4 Cartography in the European Enlightenment 5 Cartography in the Nineteenth Century 6 Cartography in the Twentieth Century THE HISTORY OF CARTOGRAPHY VOLUME THREE Cartography in the European Renaissance PART 1 Edited by DAVID WOODWARD THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS • CHICAGO & LONDON David Woodward was the Arthur H. Robinson Professor Emeritus of Geography at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London © 2007 by the University of Chicago All rights reserved. Published 2007 Printed in the United States of America 1615141312111009080712345 Set ISBN-10: 0-226-90732-5 (cloth) ISBN-13: 978-0-226-90732-1 (cloth) Part 1 ISBN-10: 0-226-90733-3 (cloth) ISBN-13: 978-0-226-90733-8 (cloth) Part 2 ISBN-10: 0-226-90734-1 (cloth) ISBN-13: 978-0-226-90734-5 (cloth) Editorial work on The History of Cartography is supported in part by grants from the Division of Preservation and Access of the National Endowment for the Humanities and the Geography and Regional Science Program and Science and Society Program of the National Science Foundation, independent federal agencies. -

General Index

General Index Italic page numbers refer to illustrations. Authors are listed in ical Index. Manuscripts, maps, and charts are usually listed by this index only when their ideas or works are discussed; full title and author; occasionally they are listed under the city and listings of works as cited in this volume are in the Bibliograph- institution in which they are held. CAbbas I, Shah, 47, 63, 65, 67, 409 on South Asian world maps, 393 and Kacba, 191 "Jahangir Embracing Shah (Abbas" Abywn (Abiyun) al-Batriq (Apion the in Kitab-i balJriye, 232-33, 278-79 (painting), 408, 410, 515 Patriarch), 26 in Kitab ~urat ai-arc!, 169 cAbd ai-Karim al-Mi~ri, 54, 65 Accuracy in Nuzhat al-mushtaq, 169 cAbd al-Rabman Efendi, 68 of Arabic measurements of length of on Piri Re)is's world map, 270, 271 cAbd al-Rabman ibn Burhan al-Maw~ili, 54 degree, 181 in Ptolemy's Geography, 169 cAbdolazlz ibn CAbdolgani el-Erzincani, 225 of Bharat Kala Bhavan globe, 397 al-Qazwlni's world maps, 144 Abdur Rahim, map by, 411, 412, 413 of al-BlrunI's calculation of Ghazna's on South Asian world maps, 393, 394, 400 Abraham ben Meir ibn Ezra, 60 longitude, 188 in view of world landmass as bird, 90-91 Abu, Mount, Rajasthan of al-BlrunI's celestial mapping, 37 in Walters Deniz atlast, pl.23 on Jain triptych, 460 of globes in paintings, 409 n.36 Agapius (Mabbub) religious map of, 482-83 of al-Idrisi's sectional maps, 163 Kitab al- ~nwan, 17 Abo al-cAbbas Abmad ibn Abi cAbdallah of Islamic celestial globes, 46-47 Agnese, Battista, 279, 280, 282, 282-83 Mu\:lammad of Kitab-i ba/Jriye, 231, 233 Agnicayana, 308-9, 309 Kitab al-durar wa-al-yawaqft fi 11m of map of north-central India, 421, 422 Agra, 378 n.145, 403, 436, 448, 476-77 al-ra~d wa-al-mawaqft (Book of of maps in Gentil's atlas of Mughal Agrawala, V. -

A Unified Plane Coordinate Reference System

This dissertation has been microfilmed exactly as received COLVOCORESSES, Alden Partridge, 1918- A UNIFIED PLANE COORDINATE REFERENCE SYSTEM. The Ohio State University, Ph.D., 1965 Geography University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan A UNIFIED PLANE COORDINATE REFERENCE SYSTEM DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University Alden P. Colvocoresses, B.S., M.Sc. Lieutenant Colonel, Corps of Engineers United States Army * * * * * The Ohio State University 1965 Approved by Adviser Department of Geodetic Science PREFACE This dissertation was prepared while the author was pursuing graduate studies at The Ohio State University. Although attending school under order of the United States Army, the views and opinions expressed herein represent solely those of the writer. A list of individuals and agencies contributing to this paper is presented as Appendix B. The author is particularly indebted to two organizations, The Ohio State University and the Army Map Service. Without the combined facilities of these two organizations the preparation of this paper could not have been accomplished. Dr. Ivan Mueller of the Geodetic Science Department of The Ohio State University served as adviser and provided essential guidance and counsel. ii VITA September 23, 1918 Born - Humboldt, Arizona 1941 oo.oo.o BoS. in Mining Engineering, University of Arizona 1941-1945 .... Military Service, European Theatre 1946-1950 o . o Mining Engineer, Magma Copper -

Early & Rare World Maps, Atlases & Rare Books

19219a_cover.qxp:Layout 1 5/10/11 12:48 AM Page 1 EARLY & RARE WORLD MAPS, ATLASES & RARE BOOKS Mainly from a Private Collection MARTAYAN LAN CATALOGUE 70 EAST 55TH STREET • NEW YORK, NEW YORK 10022 45 To Order or Inquire: Telephone: 800-423-3741 or 212-308-0018 Fax: 212-308-0074 E-Mail: [email protected] Website: www.martayanlan.com Gallery Hours: Monday through Friday 9:30 to 5:30 Saturday and Evening Hours by Appointment. We welcome any questions you might have regarding items in the catalogue. Please let us know of specific items you are seeking. We are also happy to discuss with you any aspect of map collecting. Robert Augustyn Richard Lan Seyla Martayan James Roy Terms of Sale: All items are sent subject to approval and can be returned for any reason within a week of receipt. All items are original engrav- ings, woodcuts or manuscripts and guaranteed as described. New York State residents add 8.875 % sales tax. Personal checks, Visa, MasterCard, American Express, and wire transfers are accepted. To receive periodic updates of recent acquisitions, please contact us or register on our website. Catalogue 45 Important World Maps, Atlases & Geographic Books Mainly from a Private Collection the heron tower 70 east 55th street new york, new york 10022 Contents Item 1. Isidore of Seville, 1472 p. 4 Item 2. C. Ptolemy, 1478 p. 7 Item 3. Pomponius Mela, 1482 p. 9 Item 4. Mer des hystoires, 1491 p. 11 Item 5. H. Schedel, 1493, Nuremberg Chronicle p. 14 Item 6. Bergomensis, 1502, Supplementum Chronicum p. -

Gising Dead-Reckoning; Historic Maritime Maps in GIS Menne KOSIAN

13 th International Congress „Cultural Heritage and New Technologies“ Vienna, 2008 GISing dead-reckoning; historic maritime maps in GIS Menne KOSIAN Abstract: The Dutch mapmakers of the 16th and 17th century were famous for their accurate and highly detailed maps. Several atlases were produced and were the pride and joy of many a captain, whether Dutch, English, French, fighting or merchant navy. For modern eyes, these maps often seem warped and inaccurate; besides, in those times it still was impossible to accurately determine ones longitude, so how could these maps be accurate at all? But since these maps were actually used to navigate on, and (most of) the ships actually made it to their destination and back, the information on the maps should have been accurate enough. Using old navigational techniques and principles it is possible to place these maps, and the wealth of information depicted on them, in a modern GIS. That way these old basic-data not only provides us with an insight in the development of our rich maritime landscape over the centuries, but also gives an almost personal insight in the mind of the captains using them and the command structure of the fleets dominating the high seas. Keywords: historic Dutch maritime maps, georeferencing historic data, maritime archaeology Introduction The Dutch maps from the 16th and 17th centuries were famous for their accuracy and detail level. These charts were also very popular with seafarers, both in the Netherlands, as in other seafaring nations of that time. Many of those charts had, in addition to the editions for actual navigational use also editions for presentation, often beautifully coloured and bound together into atlases. -

Chalk Map of Australia

Chalk Map of Australia Compton Chamberlayne During World War 1, the Australian soldiers, belonging to the Australian Imperial Force, were based at the Military Camp at Hurdcott. In 1916, volunteer soldiers dug out an outline of Australia, with the word “Australia” inside the map, into the northern slope of Compton Down. They created this large map overlooking the Hurdcott Camp, on the ridge of Burcombe Ivers, southeast of the village of Compton Chamberlayne. On the chalk downs, above the neighbouring village of Fovant, a few miles west of Compton Chamberlayne, there were some twenty discernible military badges that had been carved into the surface of the chalk downs by the end of World War 1. Apparently a large figure of a kangaroo had also been carved into the hillside in the area. (Photo showing Hurdcott Camp & the Map of Australia overlooking the Camp) The map of Australia was constructed by volunteer Australian soldiers by excavating a series of shallow bedding trenches into which clean chalk rubble was inserted and compressed into place. It is believed that the work took 17 weeks to complete. ©Wiltshire OPC Project/ Cathy Sedgwick/2012 In a letter to his family, dated 27th January, 1918, an Australian soldier named Thomas James Quinn wrote: “I am enclosing a map of Australia on the hill here at Hurdcott. It is done with white chalk stone & is longingly watched by the troops camped here.” An extract from the Diary of Cpl Ivor Alexander Williams, Service number 538 of 21st Battalion Australian Imperial Force, dated 13th October, 1917: “Our camp has been shifted so today I had to find them at Fovant (about 2 miles from Dinton) Oh! The scenery is just lovely. -

Map Projections

Map Projections Chapter 4 Map Projections What is map projection? Why are map projections drawn? What are the different types of projections? Which projection is most suitably used for which area? In this chapter, we will seek the answers of such essential questions. MAP PROJECTION Map projection is the method of transferring the graticule of latitude and longitude on a plane surface. It can also be defined as the transformation of spherical network of parallels and meridians on a plane surface. As you know that, the earth on which we live in is not flat. It is geoid in shape like a sphere. A globe is the best model of the earth. Due to this property of the globe, the shape and sizes of the continents and oceans are accurately shown on it. It also shows the directions and distances very accurately. The globe is divided into various segments by the lines of latitude and longitude. The horizontal lines represent the parallels of latitude and the vertical lines represent the meridians of the longitude. The network of parallels and meridians is called graticule. This network facilitates drawing of maps. Drawing of the graticule on a flat surface is called projection. But a globe has many limitations. It is expensive. It can neither be carried everywhere easily nor can a minor detail be shown on it. Besides, on the globe the meridians are semi-circles and the parallels 35 are circles. When they are transferred on a plane surface, they become intersecting straight lines or curved lines. 2021-22 Practical Work in Geography NEED FOR MAP PROJECTION The need for a map projection mainly arises to have a detailed study of a 36 region, which is not possible to do from a globe. -

Mapping Our World: Terra Incognita to Australia

XIV Mapping our world The maps seemed to have a life which was essentially XV paradoxical, being both ancient and contemporary in the same moment. They showed recognisable worlds which had been changed by more recent knowledge and cartographic handiwork, and yet preserved the past in the Matthew Flinders, General Chart of Terra Australis Maps are perhaps the most intriguing and revealing of immediacy and colour of the present. or Australia: showing the parts explored between 1798 visual documents. Their presence is felt from the first The thoughtful gaze of viewers was generously reciprocated and 1803 by M. Flinders Commr. of H.M.S. Investigator experience of a school atlas or globe to Google maps of by the rich, storied surfaces of the encyclopaedic array of (detail), London, 1814 (corrected to 1822) our backyards and streets. The form and content of maps charts, globes and atlases. Whether they visited because NATIONAL LIBRARY OF AUSTRALIA, CANBERRA, have changed markedly over the centuries, and Mapping TOOLEY COLLECTION, MAP T 1494 they loved maps, were map collectors, or just wanted Our World: Terra Incognita to Australia takes as one of its to experience the rarity and splendour of a memorable starting points this fascinating story of transformation: cartographic exhibition was hard to determine. The maps the development of cartography since the first speculative in these exhibitions seemed to make viewers slow down, maps emerged from the ancient world. Piece by piece, and perhaps travel a little way with the mapmaker, beyond through imagination and exploration, the world has aspects of cartography and history and into the realm of been charted, often at great cost, and now in the early the imagination. -

Mercator.Pdf

Name Class Date THE BEGINNINGS OF OUR GLOBAL AGE: EUROPE, AFRICA, AND ASIA Primary Source Most people today take accurate maps for granted. During the Age of Exploration, however, the maps that European explorers used were primitive. Large areas of Earth were barely known or completely unknown to them. Gerard Mercator, a Flemish car- tographer, drew the first map of the world. His design was so clever that many of his ideas are still used today. ◆ As you read, imagine how Mercator went about making his map. Then, on a separate sheet of paper, answer the questions that follow. 1569 Map of the World by Gerard Mercator (1512–1594) Gerard Mercator was born in Flanders, which is part of modern-day Belgium. He was the most important European mapmaker of the 1500s. He produced many maps before creat- ing his famous map of the world. Mercator’s goal in producing his map was to create a guide for navigators, not just to show newly explored lands. On his map, lines of longitude (meridians) and latitude (parallels) are straight, parallel lines. This would become known as the Mercator projec- tion. Geographic features like oceans and continents fit into this grid. Using Mercator’s map, navigators could plot straight-line courses over long distances without taking continuous compass readings. On the other hand, Mercator’s map, like all flat maps, had important drawbacks. The most serious is comparative size. Because the parallel lines are straight, the scale is dis- torted. Areas at the top and bottom of the map appear much larger than they really are.