Mapping Our World: Terra Incognita to Australia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Geographic Board Games

GSR_3 Geospatial Science Research 3. School of Mathematical and Geospatial Science, RMIT University December 2014 Geographic Board Games Brian Quinn and William Cartwright School of Mathematical and Geospatial Sciences RMIT University, Australia Email: [email protected] Abstract Geographic Board Games feature maps. As board games developed during the Early Modern Period, 1450 to 1750/1850, the maps that were utilised reflected the contemporary knowledge of the Earth and the cartography and surveying technologies at their time of manufacture and sale. As ephemera of family life, many board games have not survived, but those that do reveal an entertaining way of learning about the geography, exploration and politics of the world. This paper provides an introduction to four Early Modern Period geographical board games and analyses how changes through time reflect the ebb and flow of national and imperial ambitions. The portrayal of Australia in three of the games is examined. Keywords: maps, board games, Early Modern Period, Australia Introduction In this selection of geographic board games, maps are paramount. The games themselves tend to feature a throw of the dice and moves on a set path. Obstacles and hazards often affect how quickly a player gets to the finish and in a competitive situation whether one wins, or not. The board games examined in this paper were made and played in the Early Modern Period which according to Stearns (2012) dates from 1450 to 1750/18501. In this period printing gradually improved and books and journals became more available, at least to the well-off. Science developed using experimental techniques and real world observation; relying less on classical authority. -

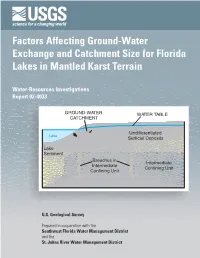

Factors Affecting Ground-Water Exchange and Catchment Size for Florida Lakes in Mantled Karst Terrain

Factors Affecting Ground-Water Exchange and Catchment Size for Florida Lakes in Mantled Karst Terrain Water-Resources Investigations Report 02-4033 GROUND-WATER WATER TABLE CATCHMENT Undifferentiated Lake Surficial Deposits Lake Sediment Breaches in Intermediate Intermediate Confining Unit Confining Unit U.S. Geological Survey Prepared in cooperation with the Southwest Florida Water Management District and the St. Johns River Water Management District Factors Affecting Ground-Water Exchange and Catchment Size for Florida Lakes in Mantled Karst Terrain By T.M. Lee U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Water-Resources Investigations Report 02-4033 Prepared in cooperation with the SOUTHWEST FLORIDA WATER MANAGEMENT DISTRICT and the ST. JOHNS RIVER WATER MANAGEMENT DISTRICT Tallahassee, Florida 2002 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR GALE A. NORTON, Secretary U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY CHARLES G. GROAT, Director The use of firm, trade, and brand names in this report is for identification purposes only and does not constitute endorsement by the U.S. Geological Survey. For additional information Copies of this report can be write to: purchased from: District Chief U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Geological Survey Branch of Information Services Suite 3015 Box 25286 227 N. Bronough Street Denver, CO 80225-0286 Tallahassee, FL 32301 888-ASK-USGS Additional information about water resources in Florida is available on the World Wide Web at http://fl.water.usgs.gov CONTENTS Abstract................................................................................................................................................................................. -

![Or Later, but Before 1650] 687X868mm. Copper Engraving On](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3632/or-later-but-before-1650-687x868mm-copper-engraving-on-163632.webp)

Or Later, but Before 1650] 687X868mm. Copper Engraving On

60 Willem Janszoon BLAEU (1571-1638). Pascaarte van alle de Zécuften van EUROPA. Nieulycx befchreven door Willem Ianfs. Blaw. Men vintfe te coop tot Amsterdam, Op't Water inde vergulde Sonnewÿser. [Amsterdam, 1621 or later, but before 1650] 687x868mm. Copper engraving on parchment, coloured by a contemporary hand. Cropped, as usual, on the neat line, to the right cut about 5mm into the printed area. The imprint is on places somewhat weaker and /or ink has been faded out. One small hole (1,7x1,4cm.) in lower part, inland of Russia. As often, the parchment is wavy, with light water staining, usual staining and surface dust. First state of two. The title and imprint appear in a cartouche, crowned by the printer's mark of Willem Jansz Blaeu [INDEFESSVS AGENDO], at the center of the lower border. Scale cartouches appear in four corners of the chart, and richly decorated coats of arms have been engraved in the interior. The chart is oriented to the west. It shows the seacoasts of Europe from Novaya Zemlya and the Gulf of Sydra in the east, and the Azores and the west coast of Greenland in the west. In the north the chart extends to the northern coast of Spitsbergen, and in the south to the Canary Islands. The eastern part of the Mediterranean id included in the North African interior. The chart is printed on parchment and coloured by a contemporary hand. The colours red and green and blue still present, other colours faded. An intriguing line in green colour, 34 cm long and about 3mm bold is running offshore the Norwegian coast all the way south of Greenland, and closely following Tara Polar Arctic Circle ! Blaeu's chart greatly influenced other Amsterdam publisher's. -

Water Flow in the Silurian-Devonian Aquifer System, Johnson County, Iowa

Hydrogeology and Simulation of Ground- Water Flow in the Silurian-Devonian Aquifer System, Johnson County, Iowa By Patrick Tucci (U.S. Geological Survey) and Robert M. McKay (Iowa Department of Natural Resources, Iowa Geological Survey) Prepared in cooperation with The Iowa Department of Natural Resources – Water Supply Bureau City of Iowa City Johnson County Board of Supervisors City of Coralville The University of Iowa City of North Liberty City of Solon Scientific Investigations Report 2005–5266 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior Gale A. Norton, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey P. Patrick Leahy, Acting Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2006 For product and ordering information: World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS For more information on the USGS--the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment: World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this report is in the public domain, permission must be secured from the individual copyright owners to reproduce any copyrighted materials contained within this report. Suggested citation: Tucci, Patrick and McKay, Robert, 2006, Hydrogeology and simulation of ground-water flow in the Silurian-Devonian aquifer system, Johnson County, Iowa: U.S. Geological Survey, Scientific Investigations -

The History of Cartography, Volume 3

THE HISTORY OF CARTOGRAPHY VOLUME THREE Volume Three Editorial Advisors Denis E. Cosgrove Richard Helgerson Catherine Delano-Smith Christian Jacob Felipe Fernández-Armesto Richard L. Kagan Paula Findlen Martin Kemp Patrick Gautier Dalché Chandra Mukerji Anthony Grafton Günter Schilder Stephen Greenblatt Sarah Tyacke Glyndwr Williams The History of Cartography J. B. Harley and David Woodward, Founding Editors 1 Cartography in Prehistoric, Ancient, and Medieval Europe and the Mediterranean 2.1 Cartography in the Traditional Islamic and South Asian Societies 2.2 Cartography in the Traditional East and Southeast Asian Societies 2.3 Cartography in the Traditional African, American, Arctic, Australian, and Pacific Societies 3 Cartography in the European Renaissance 4 Cartography in the European Enlightenment 5 Cartography in the Nineteenth Century 6 Cartography in the Twentieth Century THE HISTORY OF CARTOGRAPHY VOLUME THREE Cartography in the European Renaissance PART 1 Edited by DAVID WOODWARD THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS • CHICAGO & LONDON David Woodward was the Arthur H. Robinson Professor Emeritus of Geography at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London © 2007 by the University of Chicago All rights reserved. Published 2007 Printed in the United States of America 1615141312111009080712345 Set ISBN-10: 0-226-90732-5 (cloth) ISBN-13: 978-0-226-90732-1 (cloth) Part 1 ISBN-10: 0-226-90733-3 (cloth) ISBN-13: 978-0-226-90733-8 (cloth) Part 2 ISBN-10: 0-226-90734-1 (cloth) ISBN-13: 978-0-226-90734-5 (cloth) Editorial work on The History of Cartography is supported in part by grants from the Division of Preservation and Access of the National Endowment for the Humanities and the Geography and Regional Science Program and Science and Society Program of the National Science Foundation, independent federal agencies. -

General Index

General Index Italic page numbers refer to illustrations. Authors are listed in ical Index. Manuscripts, maps, and charts are usually listed by this index only when their ideas or works are discussed; full title and author; occasionally they are listed under the city and listings of works as cited in this volume are in the Bibliograph- institution in which they are held. CAbbas I, Shah, 47, 63, 65, 67, 409 on South Asian world maps, 393 and Kacba, 191 "Jahangir Embracing Shah (Abbas" Abywn (Abiyun) al-Batriq (Apion the in Kitab-i balJriye, 232-33, 278-79 (painting), 408, 410, 515 Patriarch), 26 in Kitab ~urat ai-arc!, 169 cAbd ai-Karim al-Mi~ri, 54, 65 Accuracy in Nuzhat al-mushtaq, 169 cAbd al-Rabman Efendi, 68 of Arabic measurements of length of on Piri Re)is's world map, 270, 271 cAbd al-Rabman ibn Burhan al-Maw~ili, 54 degree, 181 in Ptolemy's Geography, 169 cAbdolazlz ibn CAbdolgani el-Erzincani, 225 of Bharat Kala Bhavan globe, 397 al-Qazwlni's world maps, 144 Abdur Rahim, map by, 411, 412, 413 of al-BlrunI's calculation of Ghazna's on South Asian world maps, 393, 394, 400 Abraham ben Meir ibn Ezra, 60 longitude, 188 in view of world landmass as bird, 90-91 Abu, Mount, Rajasthan of al-BlrunI's celestial mapping, 37 in Walters Deniz atlast, pl.23 on Jain triptych, 460 of globes in paintings, 409 n.36 Agapius (Mabbub) religious map of, 482-83 of al-Idrisi's sectional maps, 163 Kitab al- ~nwan, 17 Abo al-cAbbas Abmad ibn Abi cAbdallah of Islamic celestial globes, 46-47 Agnese, Battista, 279, 280, 282, 282-83 Mu\:lammad of Kitab-i ba/Jriye, 231, 233 Agnicayana, 308-9, 309 Kitab al-durar wa-al-yawaqft fi 11m of map of north-central India, 421, 422 Agra, 378 n.145, 403, 436, 448, 476-77 al-ra~d wa-al-mawaqft (Book of of maps in Gentil's atlas of Mughal Agrawala, V. -

Seacare Authority Exemption

EXEMPTION 1—SCHEDULE 1 Official IMO Year of Ship Name Length Type Number Number Completion 1 GIANT LEAP 861091 13.30 2013 Yacht 1209 856291 35.11 1996 Barge 2 DREAM 860926 11.97 2007 Catamaran 2 ITCHY FEET 862427 12.58 2019 Catamaran 2 LITTLE MISSES 862893 11.55 2000 857725 30.75 1988 Passenger vessel 2001 852712 8702783 30.45 1986 Ferry 2ABREAST 859329 10.00 1990 Catamaran Pleasure Yacht 2GETHER II 859399 13.10 2008 Catamaran Pleasure Yacht 2-KAN 853537 16.10 1989 Launch 2ND HOME 856480 10.90 1996 Launch 2XS 859949 14.25 2002 Catamaran 34 SOUTH 857212 24.33 2002 Fishing 35 TONNER 861075 9714135 32.50 2014 Barge 38 SOUTH 861432 11.55 1999 Catamaran 55 NORD 860974 14.24 1990 Pleasure craft 79 199188 9.54 1935 Yacht 82 YACHT 860131 26.00 2004 Motor Yacht 83 862656 52.50 1999 Work Boat 84 862655 52.50 2000 Work Boat A BIT OF ATTITUDE 859982 16.20 2010 Yacht A COCONUT 862582 13.10 1988 Yacht A L ROBB 859526 23.95 2010 Ferry A MORNING SONG 862292 13.09 2003 Pleasure craft A P RECOVERY 857439 51.50 1977 Crane/derrick barge A QUOLL 856542 11.00 1998 Yacht A ROOM WITH A VIEW 855032 16.02 1994 Pleasure A SOJOURN 861968 15.32 2008 Pleasure craft A VOS SANTE 858856 13.00 2003 Catamaran Pleasure Yacht A Y BALAMARA 343939 9.91 1969 Yacht A.L.S.T. JAMAEKA PEARL 854831 15.24 1972 Yacht A.M.S. 1808 862294 54.86 2018 Barge A.M.S. -

The Jagiellonian Globe, Utopia and Australia

Paper 2: The Jagiellonian Globe, Utopia and Australia Robert J. King [email protected] ABSTRACT The globe, dating from around 1510, held by the Jagiellonian University in Cracow, Poland, depicts a continent in the Indian Ocean to the east of Africa and south of India, but labeled “America”. The globe illustrates how geographers of that time struggled to reconcile the discoveries of new lands with orthodox Ptolomaic cosmography. It offers a clue as to where Thomas More located his Utopia, and may provide a cosmographic explanation for the Jave la Grande of the Dieppe school of maps. BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE From 1975 to 2002, Robert J King was secretary to various committees of the Australian Senate, including the Senate Committee on Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade. He is now an independent researcher at the National Library of Australia in Canberra with a special interest in the European expansion into the Pacific in the late 18th century. He is the author of The Secret History of the Convict Colony: Alexandro Malaspina’s report on the British settlement of New South Wales published in 1990 by Allen & Unwin. He has also authored a number of articles relating to colonial/imperial rivalry in the eighteenth century and was a contributing editor to the Hakluyt Society’s 3 volume publication, The Malaspina Expedition, 1789-1794: Journal of the Voyage by Alexandro Malaspina The Jagiellonian Globe, Utopia and Australia1 The appearance in the mid-sixteenth century of Jave la Grande in a series of mappemondes drawn by a school of cartographers centred -

Locating South China in Rodinia and Gondwana: a Fragment of Greater India Lithosphere?

Locating South China in Rodinia and Gondwana: A fragment of greater India lithosphere? Peter A. Cawood1, 2, Yuejun Wang3, Yajun Xu4, and Guochun Zhao5 1Department of Earth Sciences, University of St Andrews, North Street, St Andrews KY16 9AL, UK 2Centre for Exploration Targeting, School of Earth and Environment, University of Western Australia, 35 Stirling Highway, Crawley, WA 6009, Australia 3State Key Laboratory of Isotope Geochemistry, Guangzhou Institute of Geochemistry, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Guangzhou 510640, China 4State Key Laboratory of Biogeology and Environmental Geology, Faculty of Earth Sciences, China University of Geosciences, Wuhan 430074, China 5Department of Earth Sciences, University of Hong Kong, Pokfulam Road, Hong Kong, China ABSTRACT metamorphosed Neoproterozoic strata and From the formation of Rodinia at the end of the Mesoproterozoic to the commencement unmetamorphosed Sinian cover (Fig. 1; Zhao of Pangea breakup at the end of the Paleozoic, the South China craton fi rst formed and then and Cawood, 2012). The Cathaysia block is com- occupied a position adjacent to Western Australia and northern India. Early Neoproterozoic posed predominantly of Neoproterozoic meta- suprasubduction zone magmatic arc-backarc assemblages in the craton range in age from ca. morphic rocks, with minor Paleoproterozoic and 1000 Ma to 820 Ma and display a sequential northwest decrease in age. These relations sug- Mesoproterozoic lithologies. Archean basement gest formation and closure of arc systems through southeast-directed subduction, resulting is poorly exposed and largely inferred from the in progressive northwestward accretion onto the periphery of an already assembled Rodinia. presence of minor inherited and/or xenocrys- Siliciclastic units within an early Paleozoic succession that transgresses across the craton were tic zircons in younger rocks (Fig. -

Australasian Hydrographic Society

ARTICLE Australasian Hydrographic Society Early Hydrography Recognised Willem Janszoon Monument Unveiled in Canberra The last project commemorating the 400th anniversary of Australia first being charted took place recently in the leafy suburb of Griffith, within the Australian Capital Territory. On Saturday 20th October 2007, a three-in-one –launch was held: with the inauguration of the Willem Janszoon Commemorative Park, the issue of the Explorer’s Guide for a series of local walks and the unveiling of a Willem Janszoon Monument. The launch was organised by Australia On The Map (AOTM). Griffith and the surrounding suburbs, a predominantly diplomatic district, have the distinction of having nearly all the streets named after hydrographers, explorers or their ships. From Bass to Bougainville, from Van Diemen to Vancouver, from Cook to Carstensz, the list of avenues and boulevards include names such as Torres, Flinders, Moresby, La Perouse, Dalrymple, Hartog and, in all, totals some 150 streets and byways. Amongst such esteemed company, the dedication of a major park and monument in Janszoon’s name bares testament to his unique achievement in being the first European to chart the Australian coast, a feat he accomplished when he surveyed over 300 kilometres of Cape York in 1606. Similar to the long-awaited unveiling of the Willem de Vlamingh Monument in Perth, Western Australia, four days earlier, it has taken a long time to raise money, design and build the sculptured monument and, of course, obtain necessary sanctions and approvals. Both projects were meant to have been completed in 2006, but the end results were worth the wait. -

Cartografías De Implicación E Imaginación Geográfica En La Creación De Pars Quinta. La Tierra Austral De Guillaume Le Testu (S.XVI)

Cartografías de implicación e imaginación geográfica en la creación de Pars Quinta. La Tierra Austral de Guillaume Le Testu (s.XVI) Carolina Martínez CONICET – Universidad Nacional de San Martín / Fondation Maison des Sciences de l’Homme Resumen: En el transcurso del siglo XVI, las expectativas políticas y económicas en torno al descubrimiento de una supuestamente existente Tierra Austral condujeron a la producción de objetos cartográficos específicos. Mapas, planos y atlas insinuaron la Cuadernos de existencia de una Quinta Pars, recreando la apariencia y localización de esta tierra incógnita en distintos soportes visuales. El análisis minucioso de los doce mapas in-folio Historia Cultural que Guillaume Le Testu dedicó a Terra Australis en su Cosmographie Universelle de 1556 revela que fue la imaginación geográfica comprendida en la creación de Pars Quinta la que la convirtió en una fuerza impulsora de la expansión ultramarina en la temprana modernidad. Revista de Estudios de Historia de la Cultura, Palabras clave: Imaginación geográfica, Tierra Austral, Quinta Pars, Guillaume Le Testu, cosmografía. Mentalidades, Económica y Social Cartographies of Implication and Geographical Imagination in the Making of Pars Quinta. Guillaume Le Testu’s Terra Australis (S. XVI). Abstract: Throughout the 16th century, the political and economic expectations built Nº 9, ISSN 0719-1030, around the discovery of a supposedly existent Southern Land gave way to the production of specific cartographic objects. Maps, charts and atlases hinted at the Viña del Mar, 2020 existence of a Quinta Pars, recreating the appearance and location of this elusive land in diverse visual media. An in-depth analysis of the twelve in-folio maps Guillaume Le Testu dedicated to Terra Australis in his 1556 Cosmographie Universelle reveals it was the geographical imagination involved in the making of Pars Quinta that turned it into a driving force of overseas expansion in the Early Modern Age. -

Terra Australis 30

terra australis 30 Terra Australis reports the results of archaeological and related research within the south and east of Asia, though mainly Australia, New Guinea and island Melanesia — lands that remained terra australis incognita to generations of prehistorians. Its subject is the settlement of the diverse environments in this isolated quarter of the globe by peoples who have maintained their discrete and traditional ways of life into the recent recorded or remembered past and at times into the observable present. Since the beginning of the series, the basic colour on the spine and cover has distinguished the regional distribution of topics as follows: ochre for Australia, green for New Guinea, red for South-East Asia and blue for the Pacific Islands. From 2001, issues with a gold spine will include conference proceedings, edited papers and monographs which in topic or desired format do not fit easily within the original arrangements. All volumes are numbered within the same series. List of volumes in Terra Australis Volume 1: Burrill Lake and Currarong: Coastal Sites in Southern New South Wales. R.J. Lampert (1971) Volume 2: Ol Tumbuna: Archaeological Excavations in the Eastern Central Highlands, Papua New Guinea. J.P. White (1972) Volume 3: New Guinea Stone Age Trade: The Geography and Ecology of Traffic in the Interior. I. Hughes (1977) Volume 4: Recent Prehistory in Southeast Papua. B. Egloff (1979) Volume 5: The Great Kartan Mystery. R. Lampert (1981) Volume 6: Early Man in North Queensland: Art and Archaeology in the Laura Area. A. Rosenfeld, D. Horton and J. Winter (1981) Volume 7: The Alligator Rivers: Prehistory and Ecology in Western Arnhem Land.