Institute of Commonwealth Studies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nelson-Mandelas-Legacy.Pdf

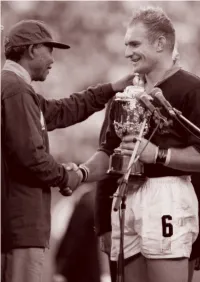

Nelson Mandela’s Legacy What the World Must Learn from One of Our Greatest Leaders By John Carlin ver since Nelson Mandela became president of South Africa after winning his Ecountry’s fi rst democratic elections in April 1994, the national anthem has consisted of two songs spliced—not particularly mellifl uously—together. One is “Nkosi Sikelel’ iAfrika,” or “God Bless Africa,” sung at black protest ral- lies during the forty-six years between the rise and fall of apartheid. The other is “Die Stem,” (“The Call”), the old white anthem, a celebration of the European settlers’ conquest of Africa’s southern tip. It was Mandela’s idea to juxtapose the two, his purpose being to forge from the rival tunes’ discordant notes a powerfully symbolic message of national harmony. Not everyone in Mandela’s party, the African National Congress, was con- vinced when he fi rst proposed the plan. In fact, the entirety of the ANC’s national executive committee initially pushed to scrap “Die Stem” and replace it with “Nkosi Sikelel’ iAfrika.” Mandela won the argument by doing what defi ned his leadership: reconciling generosity with pragmatism, fi nding common ground between humanity’s higher values and the politician’s aspiration to power. The chief task the ANC would have upon taking over government, Mandela reminded his colleagues at the meeting, would be to cement the foundations of the hard-won new democracy. The main threat to peace and stability came from right-wing terrorism. The way to deprive the extremists of popular sup- port, and therefore to disarm them, was by convincing the white population as a whole President Nelson Mandela and that they belonged fully in the ‘new South Francois Pienaar, captain of the Africa,’ that a black-led government would South African Springbok rugby not treat them the way previous white rulers team, after the Rugby World Cup had treated blacks. -

PRENEGOTIATION Ln SOUTH AFRICA (1985 -1993) a PHASEOLOGICAL ANALYSIS of the TRANSITIONAL NEGOTIATIONS

PRENEGOTIATION lN SOUTH AFRICA (1985 -1993) A PHASEOLOGICAL ANALYSIS OF THE TRANSITIONAL NEGOTIATIONS BOTHA W. KRUGER Thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts at the University of Stellenbosch. Supervisor: ProfPierre du Toit March 1998 Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za DECLARATION I, the undersigned, hereby declare that the work contained in this thesis is my own original work and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it at any university for a degree. Signature: Date: The fmancial assistance of the Centre for Science Development (HSRC, South Africa) towards this research is hereby acknowledged. Opinions expressed and conclusions arrived at, are those of the author and are not necessarily to be attributed to the Centre for Science Development. Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za OPSOMMING Die opvatting bestaan dat die Suid-Afrikaanse oorgangsonderhandelinge geinisieer is deur gebeurtenisse tydens 1990. Hierdie stuC.:ie betwis so 'n opvatting en argumenteer dat 'n noodsaaklike tydperk van informele onderhandeling voor formele kontak bestaan het. Gedurende die voorafgaande tydperk, wat bekend staan as vooronderhandeling, het lede van die Nasionale Party regering en die African National Congress (ANC) gepoog om kommunikasiekanale daar te stel en sodoende die moontlikheid van 'n onderhandelde skikking te ondersoek. Deur van 'n fase-benadering tot onderhandeling gebruik te maak, analiseer hierdie studie die oorgangstydperk met die doel om die struktuur en funksies van Suid-Afrikaanse vooronderhandelinge te bepaal. Die volgende drie onderhandelingsfases word onderskei: onderhande/ing oor onderhandeling, voorlopige onderhande/ing, en substantiewe onderhandeling. Beide fases een en twee word beskou as deel van vooronderhandeling. -

The Rollback of South Africa's Chemical and Biological Warfare

The Rollback of South Africa’s Chemical and Biological Warfare Program Stephen Burgess and Helen Purkitt US Air Force Counterproliferation Center Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama THE ROLLBACK OF SOUTH AFRICA’S CHEMICAL AND BIOLOGICAL WARFARE PROGRAM by Dr. Stephen F. Burgess and Dr. Helen E. Purkitt USAF Counterproliferation Center Air War College Air University Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama The Rollback of South Africa’s Chemical and Biological Warfare Program Dr. Stephen F. Burgess and Dr. Helen E. Purkitt April 2001 USAF Counterproliferation Center Air War College Air University Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama 36112-6427 The internet address for the USAF Counterproliferation Center is: http://www.au.af.mil/au/awc/awcgate/awc-cps.htm . Contents Page Disclaimer.....................................................................................................i The Authors ............................................................................................... iii Acknowledgments .......................................................................................v Chronology ................................................................................................vii I. Introduction .............................................................................................1 II. The Origins of the Chemical and Biological Warfare Program.............3 III. Project Coast, 1981-1993....................................................................17 IV. Rollback of Project Coast, 1988-1994................................................39 -

The Rise of the South African Security Establishment an Essay on the Changing Locus of State Power

BRADLOW SERIE£ r NUMBER ONE - ft \\ \ "*\\ The Rise of the South African Security Establishment An Essay on the Changing Locus of State Power Kenneth W. Grundy THl U- -" , ., • -* -, THE SOUTH AFRICAN INSTITUTE OF INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS The Rise of the South African Security Establishment An Essay on the Changing Locus of State Power Kenneth W, Grundy THE SOUTH AFRICAN INSTITUTE OF INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS August 1983 BRADLOW PAPER NO. 1 THE BRADLOW FELLOWSHIP The Bradlow Fellowship is awarded from a grant made to the South African Institute of In- ternational Affairs from the funds of the Estate late H. Bradlow. Kenneth W. Grundy is Professor of Political Science at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, Ohio. Professor Grundy is considered an authority on the role of the military in African affairs. In 1982, Professor Grundy was elected the first Bradlow Fellow at the South African Institute of International Affairs. Founded in Cape Town in 1934, the South African Institute of International Affairs is a fully independent national organisation whose aims are to promote a wider and more informed understanding of international issues — particularly those affecting South Africa — through objective research, study, the dissemination of information and communication between people concerned with these issues, within and outside South Africa. The Institute is privately funded by its corporate and individual members. Although Jan Smuts House is on the Witwatersrand University campus, the Institute is administratively and financially independent. It does not receive government funds from any source. Membership is open to all, irrespective of race, creed or sex, who have a serious interest in international affairs. -

Apartheid South Africa Xolela Mangcu 105 5 the State of Local Government: Third-Generation Issues Doreen Atkinson 118

ress.ac.za ress.ac.za p State of the Nation South Africa 2003–2004 Free download from www.hsrc Edited by John Daniel, Adam Habib & Roger Southall ress.ac.za ress.ac.za p Free download from www.hsrc ress.ac.za ress.ac.za p Compiled by the Democracy & Governance Research Programme, Human Sciences Research Council Published by HSRC Press Private Bag X9182, Cape Town, 8000, South Africa HSRC Press is an imprint of the Human Sciences Research Council Free download from www.hsrc ©2003 Human Sciences Research Council First published 2003 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. ISBN 0 7969 2024 9 Cover photograph by Yassir Booley Production by comPress Printed by Creda Communications Distributed in South Africa by Blue Weaver Marketing and Distribution, PO Box 30370, Tokai, Cape Town, South Africa, 7966. Tel/Fax: (021) 701-7302, email: [email protected]. Contents List of tables v List of figures vii ress.ac.za ress.ac.za p Acronyms ix Preface xiii Glenn Moss Introduction Adam Habib, John Daniel and Roger Southall 1 PART I: POLITICS 1 The state of the state: Contestation and race re-assertion in a neoliberal terrain Gerhard Maré 25 2 The state of party politics: Struggles within the Tripartite Alliance and the decline of opposition Free download from www.hsrc Roger Southall 53 3 An imperfect past: -

Great Expectations: Pres. PW Botha's Rubicon Speech of 1985

Pres. PW Botha’s Rubicon speech Great expectations: Pres. PW Botha’s Rubicon speech of 1985 Hermann Giliomee Department of History University of Stellenbosch The law of the Roman republic prohibited its generals from crossing with an army the Rubicon river between the Roman province of Cisalpine Gaul to the north and Italy proper to the south. The law thus protected the republic from internal military threat. When Julius Caesar crossed the Rubicon with his army in 49 BC to make his way to Rome, he broke that law and made armed conflict inevitable. He reputedly uttered the phrase: alea iacta est (“the die is cast”) Wikipedia Here is an infallible rule: a prince who is not himself wise cannot be well advised, unless he happens to put himself in the hands of one individual who looks after all his affairs and is an extremely shrewd man. Machiavelli, The Prince, p. 127 Samevatting Die toespraak wat Pres. PW Botha op 15 Augustus 1985 voor die kongres van die Nasionale Party (NP) van Natal gehou het, word algemeen erken as een van die keerpunte in die geskiedenis van die NP-regering. Daar is verwag dat die president in sy toespraak verreikende hervormings sou aankondig, wat die regering in staat sou stel om die skaakmat in onderhandelings met swart leiers en internasionale isolasie te deurbreek. Botha se toespraak is egter wyd baie negatief ontvang. Vorige artikels beklemtoon sy persoonlikheid as `n verklaring of blameer die “onrealistiese verwagtings” wat RF (Pik) Botha, Minister van Buitelandse Sake, gewek het. Hierdie artikel probeer die gebeure rondom die toespraak verklaar deur die gebeure twee weke voor die toespraak te ontleed, bestaande interpretasies van pres. -

ABSOLUTE FINAL ONEIL Dissertation

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Dealing with the Devil? Explaining the Onset of Strategic State-Terrorist Negotiations Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5td7j61f Author O'Neil, Siobhan Publication Date 2014 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Dealing with the Devil? Explaining the Onset of Strategic State-Terrorist Negotiations A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science by Siobhan O’Neil 2014 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Dealing with the Devil? Explaining the Onset of Strategic State-Terrorist Negotiations by Siobhan O’Neil Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science University of California, Los Angeles, 2014 Professor Arthur Stein, Chair Statesmen are quick to declare that they will not negotiate with terrorists. Yet, the empirical record demonstrates that, despite statements to the contrary, many states do eventually negotiate with their terrorist challengers. My dissertation examines the circumstances under which states employ strategic negotiations with terrorist groups to resolve violent conflict. I argue that only when faced with a credible and capable adversary and afforded relative freedom of action domestically will states negotiate with terrorists. To test this theory, I use a multi-method approach that incorporates a cross- national study of all known strategic negotiations from 1968-2006 and three within-case studies (Israel, Northern Ireland, and the Philippines). Initial results suggest that negotiations are employed in about 13% of terrorist campaigns, certain types of groups are privileged, and negotiations only occur when statesmen can overcome domestic ii obstacles, namely public and veto player opposition. -

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report Volume TWO Chapter ONE National Overview

VOLUME TWO Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report Volume TWO Chapter ONE National Overview I PREFACE 1 This chapter seeks to provide an overview of the context in which conflict developed and gross violations of human rights occurred. Other chapters in this volume focus specifically on the nature and extent of violations committed by the major role-players throughout the mandate period. The volume focuses specifically on the perpetrators of gross violations of human rights and attempts to understand patterns of abuse, forms of gross violations of human rights, and authorisation of and accountability for them. Sources 2 In identifying the principal organisations and individuals responsible for gross viola- tions of human rights in its mandate period, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (the Commission) had a vast range of information at its disposal. In addition to court records and press reports, it received over 21 000 statements from individuals alleg- ing that they were victims of human rights abuses and 7 124 from people requesting amnesty for acts they committed, authorised or failed to prevent. In addition, the Commission received submissions from the former State President, Mr P W Botha, political parties, a variety of civil institutions and organisations, the armed forces and other interested parties. All these submissions were seriously considered by the Commission. Through its power to subpoena witnesses, the Commission was also able to gather a considerable amount of information in section 29 and other public hearings. 3 While the Promotion of National Reconciliation and Unity Act (the Act) gave the Commission free access to whatever state archives and documents it required, in practice, access to the holdings of various security agencies was difficult, if not impossible, with the exception of the National Archives. -

The Cambridge Companion to Nelson Mandela Edited by Rita Barnard Frontmatter More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-01311-7 - The Cambridge Companion to Nelson Mandela Edited by Rita Barnard Frontmatter More information The Cambridge Companion to Nelson Mandela Nelson Mandela was one of the most revered fi gures of our time. He committed himself to a compelling political cause, suffered a long prison sentence, and led his violent and divided country to a peaceful democratic transition. His legacy, however, is not uncontested: his decision to embark on an armed struggle in the 1960s, his solitary talks with apartheid offi cials in the 1980s, and the economic policies adopted during his presidency still spark intense debate. The essays in this Companion , written by experts in history, anthropology, jurisprudence, cinema, literature, and visual studies, address these and other issues. They examine how Mandela became the icon he is today and ponder the meanings and uses of his internationally recognizable image. Their overarching concerns include Mandela’s relation to “tradition” and “modernity,” the impact of his most famous public performances, the oscillation between Africanist and non-racial positions in South Africa, and the politics of gender and national sentiment. The volume concludes with a meditation on Mandela’s legacy in the twenty-fi rst century and a detailed guide to further reading. Rita Barnard is Professor of English and Comparative Literature at the University of Pennsylvania and Professor Extraordinaire at Stellenbosch University, South Africa. She is the author of The Great Depression and the Culture of Abundance and Apartheid and Beyond: South African Writers and the Politics of Place . Her work has appeared in several important collections about South African literature and culture and in journals such as Novel , Contemporary Literature , Cultural Studies , Research in African Literatures , and Modern Fiction Studies . -

Microsoft Word Viewer

A COLD RELATIONSHIP: UNITED STATES FOREIGN POLICY TOWARDS SOUTH AFRICA, 1960 – 1990 Tjaart Barnard Thesis presented in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Military Science (Security and Africa Studies) at the Military Academy, Saldanha, Faculty of Military Science, Stellenbosch University Supervisor: Prof J.C.R. Liebenberg Co-supervisor: Lt Col (Prof) I.J. Van der Waag December 2016 Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za ii Declaration By submitting this thesis electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own, original work, that I am the sole author thereof (save to the extent explicitly otherwise stated), that reproduction and publication thereof by Stellenbosch University will not infringe any third party rights and that I have not previously in its entirety on in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. Date: December 2016 Copyright © 2016 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za iii ABSTRACT The diplomatic relations between the United States (USA) and South Africa (SA) had its birth in 1799 with the establishing of a consulate in Cape Town. Over the next two centuries the political dealings between the two countries were at times limited to almost merely acknowledgement of the other’s existence, while at other times there was very close cooperation on almost all levels of state. Diplomatic ties were strengthened during the Second World War, the Berlin Airlift and the Korean War when Americans and South Africans shared the same dugouts, flew in the same air missions, and opposed the same enemy on both the tactical as well as ideological fronts. -

“Democratic” Foreign Policy Making and the Thabo Mbeki Presidency: a Critical Study

“DEMOCRATIC” FOREIGN POLICY MAKING AND THE THABO MBEKI PRESIDENCY: A CRITICAL STUDY By John Alan Siko submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF LITERATURE AND PHILOSOPHY in the subject AFRICAN POLITICS at the UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH AFRICA SUPERVISOR: DR THABISI HOEANE MARCH 2014 Table of Contents 2 Summary 7 Key Terms 8 Declaration 9 Acknowledgements and Thanks 10 List of Acronyms 11 Chapter 1: Introduction 1.1 Introduction 14 1.2 Rationale for the Study 14 1.3 Why Examine the Mbeki Period? 17 1.4 Defining “Democratic” Decision Making in a Foreign Policy Construct 19 1.4.1 Foreign Policy Analysis as a Framework for Assessing “Democracy” in Policy Making 21 1.4.2 FPA’s Relationship with International Relations Theory 23 1.4.3 FPA as a Subset of Public Policy Studies 24 1.4.4 Limitations of FPA 25 1.5 Literature Review 26 1.6 Key Research Questions 29 1.7 Research Methodology 30 1.8 Ethical Considerations Taken Into Account 32 1.9 Challenges and Limitations of This Study 33 1.10 The Structure of the Thesis 34 1.11 Conclusion 34 Chapter 2: Analytical Framework for Assessing Foreign Policy Democratization 2.1 Introduction 36 2.2 Public Opinion as an Influence on Foreign Policy 37 2.3 Civil Society 38 2.4 The Media 39 2.5 Academics 41 2.6 Business 44 2.7 Legislatures 45 2.8 Ruling Parties 47 2.9 Government Bureaucracies 47 2.9.1 Allison’s Models 49 2.10 The Executive 50 2.11 Conclusion 53 2 Chapter 3: Narratives in South African Foreign Policy 3.1 Introduction 55 3.2 South African Foreign Policy to 1948 56 3.3 The -

Interrogating the Impact of Intelligence

Interrogating the Impact of Intelligence Pursuing, Protecting, and Promoting an Inclusive Political Transition Process in South Africa Nel Marais and Jo Davies IPS Paper 7 Abstract This paper provides a behind-the-scenes perspective on the role played by the three branches of intelligence services that resorted under the then apartheid government, during the negotiation process that led to South Africa’s transition to a democratic state. It provides a comparative insight into how, while some people employed in the Military Intelligence and the Security Branch continued to undermine efforts towards a negotiated settlement and political reform, the National Intelligence Service (NIS) worked within a strategic vision that grasped the imperative for change and was able to guide its political principals accordingly. Owing to this vision, the NIS worked to support a process that encompassed all the relevant power contenders and actors amid difficult circumstances, which often required the distinct capacities and skills of an intelligence services regime. In so doing, it was able to mitigate many of the factors and actors that sought to subvert a negotiated settlement, and played a significant role in protecting the tenuous peace and stability that were essential for smooth and successful transition. © Berghof Foundation Operations GmbH – CINEP/PPP 2014. All rights reserved. About the Publication This paper is one of four case study reports on South Africa produced in the course of the collaborative research project ‘Avoiding Conflict Relapse through Inclusive Political Settlements and State-building after Intra-State War’, running from February 2013 to February 2015. This project aims to examine the conditions for inclusive political settlements following protracted armed conflicts, with a specific focus on former armed power contenders turned state actors.