Interrogating the Impact of Intelligence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Complete Dissertation

VU Research Portal Itineraries Rousseau, N. 2019 document version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication in VU Research Portal citation for published version (APA) Rousseau, N. (2019). Itineraries: A return to the archives of the South African truth commission and the limits of counter-revolutionary warfare. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. E-mail address: [email protected] Download date: 09. Oct. 2021 VRIJE UNIVERSITEIT Itineraries A return to the archives of the South African truth commission and the limits of counter-revolutionary warfare ACADEMISCH PROEFSCHRIFT ter verkrijging van de graad Doctor aan de Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, op gezag van de rector magnificus prof.dr. V. Subramaniam, in het openbaar te verdedigen ten overstaan van de promotiecommissie van de Faculteit der Geesteswetenschappen op woensdag 20 maart 2019 om 15.45 uur in de aula van de universiteit, De Boelelaan 1105 door Nicky Rousseau geboren te Dundee, Zuid-Afrika promotoren: prof.dr. -

South·Africa in Transition

POLITICS OF HOPE AND TERROR: South ·Africa in Transition Report on Violence in South Africa by an American Friends Service Committee Study Team November 1992 The American Friends Service Committee's concern over Southern Africa has grown out of over 60 years of relationships since the first visit by a representative of the organization. In 1982 the AFSC Board of Directors approved the release of a full length book, Challenge and Hope, as a statement of its views on South Africa. Since 1977 the AFSC has had a national Southern Africa educational program in its Peace Education Division. AMERICAN FRIENDS SERVICE COMMITTEE 1501 Cherry Street Philadelphia, PA 19102 (215) 241-7000 AFSC REGIONAL OFFICES: Southeastern Region, Atlanta, Georgia 30303, 92 Piedmont Avenue, NE; Middle Atlantic Region, Baltimore, Maryland 21212, 4806 York Road; New England Region, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02140, 2161 Massachusetts Avenue; Great Lakes Region, Chicago, Illinois 60605, 59 E. Van Buren Street, Suite 1400; North Central Region, Des Moines, Iowa 50312, 4211 Grand Avenue; New York Metropolitan Region, New York, New York 10003, 15 Rutherford Place; Pacific Southwest Region, Pasadena, California 91103, 980 N. Fair Oaks Avenue; Pacific Mountain Region, San Francisco, California 94121,2160 Lake Street; Pacific Northwest Region, Seattle, Washington 98105, 814 N.E. 40th Street. CONTENTS II THE AFSC DELEGATION 1 PREFACE III POLITICS OF HOPE AND TERROR: South Africa in Transition 1 THE BASIC VIOLENCE 2 ANALYZING THE VIOLENCE 5 THE HIDDEN HAND 7 RETALIATION 9 POLICE INVESTIGATIONS 11 LESSONS FROM THE BOIPATONG MASSACRE 12 HOMELAND VIOLENCE IN CISKEI AND KWAZULU 13 HOMELAND LEADERS BUTHELEZI AND GQOZO 16 CONCLUSION 19 RECOMMENDATIONS 20 ACRONYMS 21 TEAM INTERVIEWS AND MEETINGS 22 THE AFSC DELEGATION TO SOUTH AFRICA The American Friends Service Committee's Board of Directors approved a proposal in June 1992 for a delegation to visit South Africa to study the escalating violence there. -

Constitutional Authority and Its Limitations: the Politics of Sexuality in South Africa

South Africa Constitutional Authority and its Limitations: The Politics of Sexuality in South Africa Belinda Beresford Helen Schneider Robert Sember Vagner Almeida “While the newly enfranchised have much to gain by supporting their government, they also have much to lose.” Adebe Zegeye (2001) A history of the future: Constitutional rights South Africa’s Constitutional Court is housed in an architecturally innovative complex on Constitution Hill, a 100-acre site in central Johannesburg. The site is adjacent to Hillbrow, a neighborhood of high-rise apartment buildings into which are crowded thousands of mi- grants from across the country and the continent. This is one of the country’s most densely populated, cosmopolitan and severely blighted urban areas. From its position atop Constitu- tion Hill, the Court offers views of Hillbrow’s high-rises and the distant northern suburbs where the established white elite and increasing numbers of newly affluent non-white South Africans live. Thus, while the light-filled, colorful and contemporary Constitutional Court buildings reflect the progressive and optimistic vision of post-apartheid South Africa the lo- cation is a reminder of the deeply entrenched inequalities that continue to define the rights of the majority of people in the country and the continent. CONSTITUTIONAL AUTHORITY AND ITS LIMITATIONS: THE POLITICS OF SEXUALITY IN SOUTH AFRICA 197 From the late 1800s to 1983 Constitution Hill was the location of Johannesburg’s central prison, the remains of which now lie in the shadow of the new court buildings. Former prison buildings include a fort built by the Boers (descendents of Dutch settlers) in the late 1800s to defend themselves against the thousands of men and women who arrived following the discovery of the area’s expansive gold deposits. -

Have You Heard from Johannesburg?

Discussion Have You Heard from GuiDe Johannesburg Have You Heard Campaign support from major funding provided By from JoHannesburg Have You Heard from Johannesburg The World Against Apartheid A new documentary series by two-time Academy Award® nominee Connie Field TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 3 about the Have you Heard from johannesburg documentary series 3 about the Have you Heard global engagement project 4 using this discussion guide 4 filmmaker’s interview 6 episode synopses Discussion Questions 6 Connecting the dots: the Have you Heard from johannesburg series 8 episode 1: road to resistance 9 episode 2: Hell of a job 10 episode 3: the new generation 11 episode 4: fair play 12 episode 5: from selma to soweto 14 episode 6: the Bottom Line 16 episode 7: free at Last Extras 17 glossary of terms 19 other resources 19 What you Can do: related organizations and Causes today 20 Acknowledgments Have You Heard from Johannesburg discussion guide 3 photos (page 2, and left and far right of this page) courtesy of archive of the anti-apartheid movement, Bodleian Library, university of oxford. Center photo on this page courtesy of Clarity films. Introduction AbouT ThE Have You Heard From JoHannesburg Documentary SEries Have You Heard from Johannesburg, a Clarity films production, is a powerful seven- part documentary series by two-time academy award® nominee Connie field that shines light on the global citizens’ movement that took on south africa’s apartheid regime. it reveals how everyday people in south africa and their allies around the globe helped challenge — and end — one of the greatest injustices the world has ever known. -

Nelson-Mandelas-Legacy.Pdf

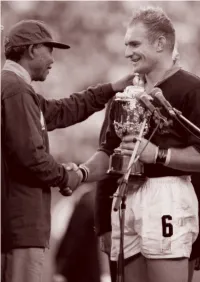

Nelson Mandela’s Legacy What the World Must Learn from One of Our Greatest Leaders By John Carlin ver since Nelson Mandela became president of South Africa after winning his Ecountry’s fi rst democratic elections in April 1994, the national anthem has consisted of two songs spliced—not particularly mellifl uously—together. One is “Nkosi Sikelel’ iAfrika,” or “God Bless Africa,” sung at black protest ral- lies during the forty-six years between the rise and fall of apartheid. The other is “Die Stem,” (“The Call”), the old white anthem, a celebration of the European settlers’ conquest of Africa’s southern tip. It was Mandela’s idea to juxtapose the two, his purpose being to forge from the rival tunes’ discordant notes a powerfully symbolic message of national harmony. Not everyone in Mandela’s party, the African National Congress, was con- vinced when he fi rst proposed the plan. In fact, the entirety of the ANC’s national executive committee initially pushed to scrap “Die Stem” and replace it with “Nkosi Sikelel’ iAfrika.” Mandela won the argument by doing what defi ned his leadership: reconciling generosity with pragmatism, fi nding common ground between humanity’s higher values and the politician’s aspiration to power. The chief task the ANC would have upon taking over government, Mandela reminded his colleagues at the meeting, would be to cement the foundations of the hard-won new democracy. The main threat to peace and stability came from right-wing terrorism. The way to deprive the extremists of popular sup- port, and therefore to disarm them, was by convincing the white population as a whole President Nelson Mandela and that they belonged fully in the ‘new South Francois Pienaar, captain of the Africa,’ that a black-led government would South African Springbok rugby not treat them the way previous white rulers team, after the Rugby World Cup had treated blacks. -

The Quest for Liberation in South Africa: Contending Visions and Civil Strife, Diaspora and Transition to an Emerging Democracy

Scientia Militaria, South African Journal of Military Studies, Vol 30, Nr 2, 2000. http://scientiamilitaria.journals.ac.za The Quest for Liberation in South Africa: Contending Visions and Civil Strife, Diaspora and Transition to an Emerging Democracy Ian Liebenberg Introduction: Purpose of this contribution To write an inclusive history of liberation and transition to democracy in South Africa is almost impossible. To do so in the course of one paper is even more demanding, if not daunting. Not only does "the liberation struggle" in South Africa in its broadest sense span more than a century. It also saw the coming and going of movements, the merging and evolving of others and a series of principled and/or pragmatic pacts in the process. The author is attempting here to provide a rather descriptive (and as far as possible, chronological) look at and rudimentary outline to the main organisational levels of liberation in South Africa since roughly the 1870' s. I will draw on my own 2 work in the field lover the past fifteen years as well as other sources • A wide variety of sources and personal experiences inform this contribution, even if they are not mentioned here. Also needless to say, one's own subjectivities may arise - even if an attempt is made towards intersubjecti vity. This article is an attempt to outline and describe the organisations (and where applicable personalities) in an inclusive and descriptive research approach in See Liebenberg (1990), ldeologie in Konjlik, Emmerentia: Taurus Uitgewers; Liebenberg & Van der Merwe (1991), Die Wordingsgeskiedenis van Apartheid, Joernaal vir Eietydse Geskiedenis, vol 16(2): 1-24; Liebenberg (1994), Resistance by the SANNC and the ANC, 1912 - 1960, in Liebenberg et al (Eds.) The Long March: The Story of the Struggle for Liberation in South Africa. -

RELIGIOUS ACTION NETWORK for Justice and Peace in Southern Africa

RELIGIOUS ACTION NETWORK for justice and peace in southern Africa a project of the American Committee on Africa ONE MORE MASSACRE by Aleah Bacquie "It seemed so absolutely unnecessary. If this is a taste of things to come, then God help us all." -John Hall, Chairperson Peace Committee God help us all indeed. Soldiers firing on unarmed peaceful demonstrators with no warning whatsoever is nothing new under the South African sun. (It was only last month that I wrote to you about the Boipatong Massacre.) Now, twenty-eight more are dead, 200 more wounded. The only fresh, but twisted slant comes from the "Gorbachevian" De Kierk, escort of the "New South Africa". You know the appalling statistics by now, nearly 8,000 people dead due to political violence since the "reformist" De Klerk began his bloody reign of terror, with tens of thousands more wounded, driven from their homes, gripped by hopelessness and fear. Complete denial of any South African governmental responsibility was expected, even though the soldiers who fired were under the command of a South African Defense Force Brigadier on loan to the "bantustan" Ciskei government. The South African government has long contended that the Black "bantustans" are independent governments, although they are not recognized by any other government, including the U.S. However, with hard evidence of government complicity mounting, De Klerk tried a new tactic, blaming the victim. He somehow mustered the gall to assert that the massacre of ANC supporters is the fault of the ANC! According to this disturbed logic, those Blacks who dared to exercise their right of peaceful assembly and protest are to blame because they should have known that Pretoria's puppet, Oupa Gqozo, would fire on the marchers. -

PRENEGOTIATION Ln SOUTH AFRICA (1985 -1993) a PHASEOLOGICAL ANALYSIS of the TRANSITIONAL NEGOTIATIONS

PRENEGOTIATION lN SOUTH AFRICA (1985 -1993) A PHASEOLOGICAL ANALYSIS OF THE TRANSITIONAL NEGOTIATIONS BOTHA W. KRUGER Thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts at the University of Stellenbosch. Supervisor: ProfPierre du Toit March 1998 Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za DECLARATION I, the undersigned, hereby declare that the work contained in this thesis is my own original work and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it at any university for a degree. Signature: Date: The fmancial assistance of the Centre for Science Development (HSRC, South Africa) towards this research is hereby acknowledged. Opinions expressed and conclusions arrived at, are those of the author and are not necessarily to be attributed to the Centre for Science Development. Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za OPSOMMING Die opvatting bestaan dat die Suid-Afrikaanse oorgangsonderhandelinge geinisieer is deur gebeurtenisse tydens 1990. Hierdie stuC.:ie betwis so 'n opvatting en argumenteer dat 'n noodsaaklike tydperk van informele onderhandeling voor formele kontak bestaan het. Gedurende die voorafgaande tydperk, wat bekend staan as vooronderhandeling, het lede van die Nasionale Party regering en die African National Congress (ANC) gepoog om kommunikasiekanale daar te stel en sodoende die moontlikheid van 'n onderhandelde skikking te ondersoek. Deur van 'n fase-benadering tot onderhandeling gebruik te maak, analiseer hierdie studie die oorgangstydperk met die doel om die struktuur en funksies van Suid-Afrikaanse vooronderhandelinge te bepaal. Die volgende drie onderhandelingsfases word onderskei: onderhande/ing oor onderhandeling, voorlopige onderhande/ing, en substantiewe onderhandeling. Beide fases een en twee word beskou as deel van vooronderhandeling. -

(Prexy) Nesbitt Anti-Apartheid Collection College Archives & Special Collections

Columbia College Chicago Digital Commons @ Columbia College Chicago Finding Aids College Archives & Special Collections 9-1-2017 Guide to the Rozell (Prexy) Nesbitt Anti-Apartheid Collection College Archives & Special Collections Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.colum.edu/casc_fa Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation "Rozell (Prexy) Nesbitt oC llection," 2017. Finding aid at the College Archives & Special Collections of Columbia College Chicago, Chicago, IL. http://digitalcommons.colum.edu/casc_fa/26/ This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the College Archives & Special Collections at Digital Commons @ Columbia College Chicago. It has been accepted for inclusion in Finding Aids by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Columbia College Chicago. Rozell (Prexy) Nesbitt Collection This finding aid was produced using ArchivesSpace on September 01, 2017. eng Describing Archives: A Content Standard College Archives & Special Collections at Columbia College Chicago Chicago, IL [email protected] URL: http://www.colum.edu/archives Rozell (Prexy) Nesbitt Collection Table of Contents Summary Information .................................................................................................................................... 4 Biography ....................................................................................................................................................... 5 About the Collection ..................................................................................................................................... -

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report: Volume 2

VOLUME TWO Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report The report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission was presented to President Nelson Mandela on 29 October 1998. Archbishop Desmond Tutu Ms Hlengiwe Mkhize Chairperson Dr Alex Boraine Mr Dumisa Ntsebeza Vice-Chairperson Ms Mary Burton Dr Wendy Orr Revd Bongani Finca Adv Denzil Potgieter Ms Sisi Khampepe Dr Fazel Randera Mr Richard Lyster Ms Yasmin Sooka Mr Wynand Malan* Ms Glenda Wildschut Dr Khoza Mgojo * Subject to minority position. See volume 5. Chief Executive Officer: Dr Biki Minyuku I CONTENTS Chapter 1 Chapter 6 National Overview .......................................... 1 Special Investigation The Death of President Samora Machel ................................................ 488 Chapter 2 The State outside Special Investigation South Africa (1960-1990).......................... 42 Helderberg Crash ........................................... 497 Special Investigation Chemical and Biological Warfare........ 504 Chapter 3 The State inside South Africa (1960-1990).......................... 165 Special Investigation Appendix: State Security Forces: Directory Secret State Funding................................... 518 of Organisations and Structures........................ 313 Special Investigation Exhumations....................................................... 537 Chapter 4 The Liberation Movements from 1960 to 1990 ..................................................... 325 Special Investigation Appendix: Organisational structures and The Mandela United -

SOUTH AFRICAN POLITICAL EXILE in the UNITED KINGDOM Al50by Mark Israel

SOUTH AFRICAN POLITICAL EXILE IN THE UNITED KINGDOM Al50by Mark Israel INTERNATIONAL VICTIMOLOGY (co-editor) South African Political Exile in the United Kingdom Mark Israel SeniorLecturer School of Law TheFlinders University ofSouth Australia First published in Great Britain 1999 by MACMILLAN PRESS LTD Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS and London Companies and representatives throughout the world A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 978-1-349-14925-4 ISBN 978-1-349-14923-0 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-1-349-14923-0 First published in the United States of Ameri ca 1999 by ST. MARTIN'S PRESS, INC., Scholarly and Reference Division. 175 Fifth Avenue. New York. N.Y. 10010 ISBN 978-0-312-22025-9 Library of Congre ss Cataloging-in-Publication Data Israel. Mark. 1965- South African political exile in the United Kingdom / Mark Israel. p. cm. Include s bibliographical references and index . ISBN 978-0-312-22025-9 (cloth) I. Political refugees-Great Britain-History-20th century. 2. Great Britain-Exiles-History-20th century. 3. South Africans -Great Britain-History-20th century. I. Title . HV640.5.S6I87 1999 362.87'0941-dc21 98-32038 CIP © Mark Israel 1999 Softcover reprint of the hardcover Ist edition 1999 All rights reserved . No reprodu ction. copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. No paragraph of this publicat ion may be reproduced. copied or transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provision s of the Copyright. Design s and Patents Act 1988. or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency . -

EB145 Opt.Pdf

E EPISCOPAL CHURCHPEOPLE for a FREE SOUTHERN AFRICA 339 Lafayette Street, New York, N.Y. 10012·2725 C (212) 4n-0066 FAX: (212) 979-1013 S A #145 21 february 1994 _SU_N_D_AY-.::..:20--:FEB:.=:..:;R..:..:U..:..:AR:..:.Y:.....:..:.1994::...::.-_---.". ----'-__THE OBSERVER_ Ten weeks before South Africa's elections, a race war looks increasingly likely, reports Phillip van Niekerk in Johannesburg TOKYO SEXWALE, the Afri In S'tanderton, in the Eastern candidate for the premiership of At the meeting in the Pretoria Many leading Inkatha mem can National Congress candidate Transvaal, the white town coun Natal. There is little doubt that showgrounds three weeks ago, bers have publicly and privately for the office of premier in the cillast Wednesday declared itself Natal will fall to the ANC on 27 when General Constand Viljoen, expressed their dissatisfaction at Pretoria-Witwatersrand-Veree part of an independent Boer April, which explains Buthelezi's head ofthe Afrikaner Volksfront, Inkatha's refusal to participate in niging province, returned shaken state, almost provoking a racial determination to wriggle out of was shouted down while advo the election, and could break from a tour of the civil war in conflagration which, for all the having to fight the dection.~ cating the route to a volkstaat not away. Angola last Thursday. 'I have violence of recent years, the At the very least, last week's very different to that announced But the real prize in Natal is seen the furure according to the country not yet experienced. concessions removed any trace of by Mandela last week, the im Goodwill Zwelithini, the Zulu right wing,' he said, vividly de The council's declaration pro a legitimate gripe against the new pression was created that the king and Buthelezi's nephew.