Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report Volume TWO Chapter ONE National Overview

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nelson-Mandelas-Legacy.Pdf

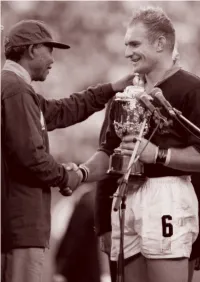

Nelson Mandela’s Legacy What the World Must Learn from One of Our Greatest Leaders By John Carlin ver since Nelson Mandela became president of South Africa after winning his Ecountry’s fi rst democratic elections in April 1994, the national anthem has consisted of two songs spliced—not particularly mellifl uously—together. One is “Nkosi Sikelel’ iAfrika,” or “God Bless Africa,” sung at black protest ral- lies during the forty-six years between the rise and fall of apartheid. The other is “Die Stem,” (“The Call”), the old white anthem, a celebration of the European settlers’ conquest of Africa’s southern tip. It was Mandela’s idea to juxtapose the two, his purpose being to forge from the rival tunes’ discordant notes a powerfully symbolic message of national harmony. Not everyone in Mandela’s party, the African National Congress, was con- vinced when he fi rst proposed the plan. In fact, the entirety of the ANC’s national executive committee initially pushed to scrap “Die Stem” and replace it with “Nkosi Sikelel’ iAfrika.” Mandela won the argument by doing what defi ned his leadership: reconciling generosity with pragmatism, fi nding common ground between humanity’s higher values and the politician’s aspiration to power. The chief task the ANC would have upon taking over government, Mandela reminded his colleagues at the meeting, would be to cement the foundations of the hard-won new democracy. The main threat to peace and stability came from right-wing terrorism. The way to deprive the extremists of popular sup- port, and therefore to disarm them, was by convincing the white population as a whole President Nelson Mandela and that they belonged fully in the ‘new South Francois Pienaar, captain of the Africa,’ that a black-led government would South African Springbok rugby not treat them the way previous white rulers team, after the Rugby World Cup had treated blacks. -

PRENEGOTIATION Ln SOUTH AFRICA (1985 -1993) a PHASEOLOGICAL ANALYSIS of the TRANSITIONAL NEGOTIATIONS

PRENEGOTIATION lN SOUTH AFRICA (1985 -1993) A PHASEOLOGICAL ANALYSIS OF THE TRANSITIONAL NEGOTIATIONS BOTHA W. KRUGER Thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts at the University of Stellenbosch. Supervisor: ProfPierre du Toit March 1998 Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za DECLARATION I, the undersigned, hereby declare that the work contained in this thesis is my own original work and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it at any university for a degree. Signature: Date: The fmancial assistance of the Centre for Science Development (HSRC, South Africa) towards this research is hereby acknowledged. Opinions expressed and conclusions arrived at, are those of the author and are not necessarily to be attributed to the Centre for Science Development. Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za OPSOMMING Die opvatting bestaan dat die Suid-Afrikaanse oorgangsonderhandelinge geinisieer is deur gebeurtenisse tydens 1990. Hierdie stuC.:ie betwis so 'n opvatting en argumenteer dat 'n noodsaaklike tydperk van informele onderhandeling voor formele kontak bestaan het. Gedurende die voorafgaande tydperk, wat bekend staan as vooronderhandeling, het lede van die Nasionale Party regering en die African National Congress (ANC) gepoog om kommunikasiekanale daar te stel en sodoende die moontlikheid van 'n onderhandelde skikking te ondersoek. Deur van 'n fase-benadering tot onderhandeling gebruik te maak, analiseer hierdie studie die oorgangstydperk met die doel om die struktuur en funksies van Suid-Afrikaanse vooronderhandelinge te bepaal. Die volgende drie onderhandelingsfases word onderskei: onderhande/ing oor onderhandeling, voorlopige onderhande/ing, en substantiewe onderhandeling. Beide fases een en twee word beskou as deel van vooronderhandeling. -

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report: Volume 2

VOLUME TWO Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report The report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission was presented to President Nelson Mandela on 29 October 1998. Archbishop Desmond Tutu Ms Hlengiwe Mkhize Chairperson Dr Alex Boraine Mr Dumisa Ntsebeza Vice-Chairperson Ms Mary Burton Dr Wendy Orr Revd Bongani Finca Adv Denzil Potgieter Ms Sisi Khampepe Dr Fazel Randera Mr Richard Lyster Ms Yasmin Sooka Mr Wynand Malan* Ms Glenda Wildschut Dr Khoza Mgojo * Subject to minority position. See volume 5. Chief Executive Officer: Dr Biki Minyuku I CONTENTS Chapter 1 Chapter 6 National Overview .......................................... 1 Special Investigation The Death of President Samora Machel ................................................ 488 Chapter 2 The State outside Special Investigation South Africa (1960-1990).......................... 42 Helderberg Crash ........................................... 497 Special Investigation Chemical and Biological Warfare........ 504 Chapter 3 The State inside South Africa (1960-1990).......................... 165 Special Investigation Appendix: State Security Forces: Directory Secret State Funding................................... 518 of Organisations and Structures........................ 313 Special Investigation Exhumations....................................................... 537 Chapter 4 The Liberation Movements from 1960 to 1990 ..................................................... 325 Special Investigation Appendix: Organisational structures and The Mandela United -

Year of Fire, Year of Ash. the Soweto Revolt: Roots of a Revolution?

Year of fire, year of ash. The Soweto revolt: roots of a revolution? http://www.aluka.org/action/showMetadata?doi=10.5555/AL.SFF.DOCUMENT.ESRSA00029 Use of the Aluka digital library is subject to Aluka’s Terms and Conditions, available at http://www.aluka.org/page/about/termsConditions.jsp. By using Aluka, you agree that you have read and will abide by the Terms and Conditions. Among other things, the Terms and Conditions provide that the content in the Aluka digital library is only for personal, non-commercial use by authorized users of Aluka in connection with research, scholarship, and education. The content in the Aluka digital library is subject to copyright, with the exception of certain governmental works and very old materials that may be in the public domain under applicable law. Permission must be sought from Aluka and/or the applicable copyright holder in connection with any duplication or distribution of these materials where required by applicable law. Aluka is a not-for-profit initiative dedicated to creating and preserving a digital archive of materials about and from the developing world. For more information about Aluka, please see http://www.aluka.org Year of fire, year of ash. The Soweto revolt: roots of a revolution? Author/Creator Hirson, Baruch Publisher Zed Books, Ltd. (London) Date 1979 Resource type Books Language English Subject Coverage (spatial) South Africa Coverage (temporal) 1799-1977 Source Enuga S. Reddy Rights By kind permission of the Estate of Baruch Hirson and Zed Books Ltd. Description Table of Contents: -

The Rollback of South Africa's Chemical and Biological Warfare

The Rollback of South Africa’s Chemical and Biological Warfare Program Stephen Burgess and Helen Purkitt US Air Force Counterproliferation Center Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama THE ROLLBACK OF SOUTH AFRICA’S CHEMICAL AND BIOLOGICAL WARFARE PROGRAM by Dr. Stephen F. Burgess and Dr. Helen E. Purkitt USAF Counterproliferation Center Air War College Air University Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama The Rollback of South Africa’s Chemical and Biological Warfare Program Dr. Stephen F. Burgess and Dr. Helen E. Purkitt April 2001 USAF Counterproliferation Center Air War College Air University Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama 36112-6427 The internet address for the USAF Counterproliferation Center is: http://www.au.af.mil/au/awc/awcgate/awc-cps.htm . Contents Page Disclaimer.....................................................................................................i The Authors ............................................................................................... iii Acknowledgments .......................................................................................v Chronology ................................................................................................vii I. Introduction .............................................................................................1 II. The Origins of the Chemical and Biological Warfare Program.............3 III. Project Coast, 1981-1993....................................................................17 IV. Rollback of Project Coast, 1988-1994................................................39 -

Music to Move the Masses: Protest Music Of

The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgement of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Published by the University of Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. University of Cape Town Music to Move the Masses: Protest Music of the 1980s as a Facilitator for Social Change in South Africa. Town Cape of Claudia Mohr University Dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Music, University of Cape Town. P a g e | 1 A project such as this is a singular undertaking, not for the faint hearted, and would surely not be achieved without help. Having said this I must express my sincere gratitude to those that have helped me. To the University of Cape Town and the National Research Foundation, as Benjamin Franklin would say ‘time is money’, and indeed I would not have been able to spend the time writing this had I not been able to pay for it, so thank you for your contribution. To my supervisor, Sylvia Bruinders. Thank you for your patience and guidance, without which I would not have been able to curb my lyrical writing style into the semblance of academic writing. To Dr. Michael Drewett and Dr. Ingrid Byerly: although I haven’t met you personally, your work has served as an inspiration to me, and ITown thank you. -

The Rise of the South African Security Establishment an Essay on the Changing Locus of State Power

BRADLOW SERIE£ r NUMBER ONE - ft \\ \ "*\\ The Rise of the South African Security Establishment An Essay on the Changing Locus of State Power Kenneth W. Grundy THl U- -" , ., • -* -, THE SOUTH AFRICAN INSTITUTE OF INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS The Rise of the South African Security Establishment An Essay on the Changing Locus of State Power Kenneth W, Grundy THE SOUTH AFRICAN INSTITUTE OF INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS August 1983 BRADLOW PAPER NO. 1 THE BRADLOW FELLOWSHIP The Bradlow Fellowship is awarded from a grant made to the South African Institute of In- ternational Affairs from the funds of the Estate late H. Bradlow. Kenneth W. Grundy is Professor of Political Science at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, Ohio. Professor Grundy is considered an authority on the role of the military in African affairs. In 1982, Professor Grundy was elected the first Bradlow Fellow at the South African Institute of International Affairs. Founded in Cape Town in 1934, the South African Institute of International Affairs is a fully independent national organisation whose aims are to promote a wider and more informed understanding of international issues — particularly those affecting South Africa — through objective research, study, the dissemination of information and communication between people concerned with these issues, within and outside South Africa. The Institute is privately funded by its corporate and individual members. Although Jan Smuts House is on the Witwatersrand University campus, the Institute is administratively and financially independent. It does not receive government funds from any source. Membership is open to all, irrespective of race, creed or sex, who have a serious interest in international affairs. -

Apartheid South Africa Xolela Mangcu 105 5 the State of Local Government: Third-Generation Issues Doreen Atkinson 118

ress.ac.za ress.ac.za p State of the Nation South Africa 2003–2004 Free download from www.hsrc Edited by John Daniel, Adam Habib & Roger Southall ress.ac.za ress.ac.za p Free download from www.hsrc ress.ac.za ress.ac.za p Compiled by the Democracy & Governance Research Programme, Human Sciences Research Council Published by HSRC Press Private Bag X9182, Cape Town, 8000, South Africa HSRC Press is an imprint of the Human Sciences Research Council Free download from www.hsrc ©2003 Human Sciences Research Council First published 2003 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. ISBN 0 7969 2024 9 Cover photograph by Yassir Booley Production by comPress Printed by Creda Communications Distributed in South Africa by Blue Weaver Marketing and Distribution, PO Box 30370, Tokai, Cape Town, South Africa, 7966. Tel/Fax: (021) 701-7302, email: [email protected]. Contents List of tables v List of figures vii ress.ac.za ress.ac.za p Acronyms ix Preface xiii Glenn Moss Introduction Adam Habib, John Daniel and Roger Southall 1 PART I: POLITICS 1 The state of the state: Contestation and race re-assertion in a neoliberal terrain Gerhard Maré 25 2 The state of party politics: Struggles within the Tripartite Alliance and the decline of opposition Free download from www.hsrc Roger Southall 53 3 An imperfect past: -

On Apartheid

1-1. " '1 11 1~~~_ISl~I!I!rl.l.IJ."""'g.1 1$ Cl.~~liíilII-••allllfijlfij.UlIN.I*!•••_.lf¡.II••t $l.'.Jli.1II¡~n.·iIIIU.!1llII.I••MA{(~IIMIl_I!M\I QMl__l1IlIIWaJJIl'M-IIII!IIIll\';I-1lII!l i I \ 1, ¡ : ¡I' ADDITIONAL REPORTS OF THE ON APARTHEID • GENERAL ASSEMBLV OFFICiAL RECORDS: TWENT\(-NINTH SESSION SUPPLEMENT No. 22A (A/9622/Add.1) ..", UNITED NATIONS 22A 1, ¡1 ,I ~,,: I1 I ADDITIONAL REPORTS OFTHE SPECIAL COMMITrEE ON APARTHEID • GENERAl. ASSEMBLY OFFICIAL RECORDS: TWENTY..NINTH SESSION SUPPLEMENT No. 22A (A/9622/Add.1) UNITED NATIONS New York, 1975 . -_JtlItIII--[iII__I!IIII!II!M'l!W__i!i__"el!~~1'~f~'::~;~_~~".__j¡lII""'''ill._.il_ftiílill§~\j . '; NOTE Syrnbols of United Natíons documents are composed of capital letters combined wíth figures. Mentíon of such a symbol indicates a reference to a United Nations documento The present volume contains the four additional reports submitted to the General Assembly, at its request, by the SpeciaI Committee on Apartheid. They were previously issued in mimeographed form under the symbols A/9780, A/9781, A/9803 and A/9804 and Corr.l , l' r1: ¡~,f.•.. L ,; , ",!, <'o,, - -'.~, --~'-~-...... ~-- •.• '~--""""~-'-"-"--'.__•• ,._.~--~ •• __ •• ~ ~"" - -,,- ~,, __._ 0-","" __ ~\, '._ .... '-i.~ ~ •. /Original: English/ CUNTENTS Page . PART ONE. REPORT ON VIOLATIONS OF THE CHARTER OF THE J"" UNITED NATIONS AND RESOLUTIONS OF THE GENERAL ASSEMBLY AND THE SECURITY COUNCIL BY THE SOUTH AFRICAN REGlME ••••••••••••• • •• • • •• • PART TWO. REPORT ON ARBITRARY LAWS AND REGULATIONS ENACTED AND APPLIED BY THE SOUTH AFRICAN REGlME TO REPRESS THE LEGITlMATE STRUGGLE FOR FREEDOM •••••••••• e•••••••••• ¡, • •• 22"" PART THREE. -

Institute of Commonwealth Studies

University of London INSTITUTE OF COMMONWEALTH STUDIES Interview with VIC ZAZERAJ Key: SO: = Sue Onslow (interviewer) VZ: = Vic Zazeraj (respondent) SO: This is Dr. Sue Onslow talking to Mr. Vic Zazeraj at TransAfrica House in Johannesburg on the 15th of April 2013. Vic, thank you very much indeed for agreeing to talk to me. I wonder if you could begin by saying, please, how did you come to join the Department of Foreign Affairs in South Africa? VZ: Much to the despair of my parents I'm afraid. My father was a Polish airman stationed in the UK during the Second World War. My mother was English, and after the War my parents immigrated to Cape Town. I did not become an engineer or a lawyer, or a doctor as my parents would have preferred. I studied political science and political history and philosophy. I was doing post- graduate studies at the University of Cape Town when I got married and then I had to find a real job. I applied at the Department of Foreign Affairs to undergo diplomatic cadet training, and to see if I could make a career in the Foreign Service. I joined the Foreign Service in 1974 in Pretoria at a time when John Vorster was still the prime minister. Dr. Hilgard Muller was the Minister of Foreign Affairs and it was a particularly crucial time in the history of southern Africa. The coup d'état had occurred in Lisbon in April of that year. It heralded the withdrawal of Portuguese interest from Mozambique and Angola. -

Great Expectations: Pres. PW Botha's Rubicon Speech of 1985

Pres. PW Botha’s Rubicon speech Great expectations: Pres. PW Botha’s Rubicon speech of 1985 Hermann Giliomee Department of History University of Stellenbosch The law of the Roman republic prohibited its generals from crossing with an army the Rubicon river between the Roman province of Cisalpine Gaul to the north and Italy proper to the south. The law thus protected the republic from internal military threat. When Julius Caesar crossed the Rubicon with his army in 49 BC to make his way to Rome, he broke that law and made armed conflict inevitable. He reputedly uttered the phrase: alea iacta est (“the die is cast”) Wikipedia Here is an infallible rule: a prince who is not himself wise cannot be well advised, unless he happens to put himself in the hands of one individual who looks after all his affairs and is an extremely shrewd man. Machiavelli, The Prince, p. 127 Samevatting Die toespraak wat Pres. PW Botha op 15 Augustus 1985 voor die kongres van die Nasionale Party (NP) van Natal gehou het, word algemeen erken as een van die keerpunte in die geskiedenis van die NP-regering. Daar is verwag dat die president in sy toespraak verreikende hervormings sou aankondig, wat die regering in staat sou stel om die skaakmat in onderhandelings met swart leiers en internasionale isolasie te deurbreek. Botha se toespraak is egter wyd baie negatief ontvang. Vorige artikels beklemtoon sy persoonlikheid as `n verklaring of blameer die “onrealistiese verwagtings” wat RF (Pik) Botha, Minister van Buitelandse Sake, gewek het. Hierdie artikel probeer die gebeure rondom die toespraak verklaar deur die gebeure twee weke voor die toespraak te ontleed, bestaande interpretasies van pres. -

ABSOLUTE FINAL ONEIL Dissertation

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Dealing with the Devil? Explaining the Onset of Strategic State-Terrorist Negotiations Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5td7j61f Author O'Neil, Siobhan Publication Date 2014 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Dealing with the Devil? Explaining the Onset of Strategic State-Terrorist Negotiations A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science by Siobhan O’Neil 2014 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Dealing with the Devil? Explaining the Onset of Strategic State-Terrorist Negotiations by Siobhan O’Neil Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science University of California, Los Angeles, 2014 Professor Arthur Stein, Chair Statesmen are quick to declare that they will not negotiate with terrorists. Yet, the empirical record demonstrates that, despite statements to the contrary, many states do eventually negotiate with their terrorist challengers. My dissertation examines the circumstances under which states employ strategic negotiations with terrorist groups to resolve violent conflict. I argue that only when faced with a credible and capable adversary and afforded relative freedom of action domestically will states negotiate with terrorists. To test this theory, I use a multi-method approach that incorporates a cross- national study of all known strategic negotiations from 1968-2006 and three within-case studies (Israel, Northern Ireland, and the Philippines). Initial results suggest that negotiations are employed in about 13% of terrorist campaigns, certain types of groups are privileged, and negotiations only occur when statesmen can overcome domestic ii obstacles, namely public and veto player opposition.