Great Expectations: Pres. PW Botha's Rubicon Speech of 1985

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Have You Heard from Johannesburg?

Discussion Have You Heard from GuiDe Johannesburg Have You Heard Campaign support from major funding provided By from JoHannesburg Have You Heard from Johannesburg The World Against Apartheid A new documentary series by two-time Academy Award® nominee Connie Field TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 3 about the Have you Heard from johannesburg documentary series 3 about the Have you Heard global engagement project 4 using this discussion guide 4 filmmaker’s interview 6 episode synopses Discussion Questions 6 Connecting the dots: the Have you Heard from johannesburg series 8 episode 1: road to resistance 9 episode 2: Hell of a job 10 episode 3: the new generation 11 episode 4: fair play 12 episode 5: from selma to soweto 14 episode 6: the Bottom Line 16 episode 7: free at Last Extras 17 glossary of terms 19 other resources 19 What you Can do: related organizations and Causes today 20 Acknowledgments Have You Heard from Johannesburg discussion guide 3 photos (page 2, and left and far right of this page) courtesy of archive of the anti-apartheid movement, Bodleian Library, university of oxford. Center photo on this page courtesy of Clarity films. Introduction AbouT ThE Have You Heard From JoHannesburg Documentary SEries Have You Heard from Johannesburg, a Clarity films production, is a powerful seven- part documentary series by two-time academy award® nominee Connie field that shines light on the global citizens’ movement that took on south africa’s apartheid regime. it reveals how everyday people in south africa and their allies around the globe helped challenge — and end — one of the greatest injustices the world has ever known. -

Nelson-Mandelas-Legacy.Pdf

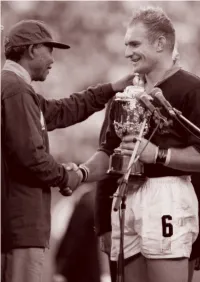

Nelson Mandela’s Legacy What the World Must Learn from One of Our Greatest Leaders By John Carlin ver since Nelson Mandela became president of South Africa after winning his Ecountry’s fi rst democratic elections in April 1994, the national anthem has consisted of two songs spliced—not particularly mellifl uously—together. One is “Nkosi Sikelel’ iAfrika,” or “God Bless Africa,” sung at black protest ral- lies during the forty-six years between the rise and fall of apartheid. The other is “Die Stem,” (“The Call”), the old white anthem, a celebration of the European settlers’ conquest of Africa’s southern tip. It was Mandela’s idea to juxtapose the two, his purpose being to forge from the rival tunes’ discordant notes a powerfully symbolic message of national harmony. Not everyone in Mandela’s party, the African National Congress, was con- vinced when he fi rst proposed the plan. In fact, the entirety of the ANC’s national executive committee initially pushed to scrap “Die Stem” and replace it with “Nkosi Sikelel’ iAfrika.” Mandela won the argument by doing what defi ned his leadership: reconciling generosity with pragmatism, fi nding common ground between humanity’s higher values and the politician’s aspiration to power. The chief task the ANC would have upon taking over government, Mandela reminded his colleagues at the meeting, would be to cement the foundations of the hard-won new democracy. The main threat to peace and stability came from right-wing terrorism. The way to deprive the extremists of popular sup- port, and therefore to disarm them, was by convincing the white population as a whole President Nelson Mandela and that they belonged fully in the ‘new South Francois Pienaar, captain of the Africa,’ that a black-led government would South African Springbok rugby not treat them the way previous white rulers team, after the Rugby World Cup had treated blacks. -

South Africa: What Kind of Change? by William J

A publication of ihe African Studies Program of The Georgetown University Center for Strategic and International Studies No.5 • November 25, 1982 South Africa: What Kind of Change? by William J. Foltz Discussion of the prospects for "meaningful" or just installed. Thanks in large part to the electoral "significant" change in South Africa has engaged success of 1948, his ethnic community has now pro Marxist, liberal, and conservative scholars for years. duced a substantial entrepreneurial and managerial Like other participants in this perennial debate, I have class which has challenged the English-speaking com tripped over my own predictions often enough to have munity for control over the economy and which is bruised my hubris. I am afraid that I must disappoint now busy integrating itself with that community. In anyone who wants a firm schedule and route map as 1948 the income ratio between Afrikaners and English to where South Africa goes from here. This does not was 1:2, it is now about 1:1.3, and in urban areas it imply that important changes are not taking place in is nearly 1:1. South Africa. Indeed, some of the changes that have The African population has also changed substan occurred or become apparent in the last seven years tially. Despite the fictions of grand apartheid, more have been momentous, and at the least they allow us than half the African population lives in "white" areas, to exclude some possibilities for the future. There are, and by the end of the century 60 percent of the total however, simply too many uncontrolled variables in African population is expected to be urban. -

The Quest for Liberation in South Africa: Contending Visions and Civil Strife, Diaspora and Transition to an Emerging Democracy

Scientia Militaria, South African Journal of Military Studies, Vol 30, Nr 2, 2000. http://scientiamilitaria.journals.ac.za The Quest for Liberation in South Africa: Contending Visions and Civil Strife, Diaspora and Transition to an Emerging Democracy Ian Liebenberg Introduction: Purpose of this contribution To write an inclusive history of liberation and transition to democracy in South Africa is almost impossible. To do so in the course of one paper is even more demanding, if not daunting. Not only does "the liberation struggle" in South Africa in its broadest sense span more than a century. It also saw the coming and going of movements, the merging and evolving of others and a series of principled and/or pragmatic pacts in the process. The author is attempting here to provide a rather descriptive (and as far as possible, chronological) look at and rudimentary outline to the main organisational levels of liberation in South Africa since roughly the 1870' s. I will draw on my own 2 work in the field lover the past fifteen years as well as other sources • A wide variety of sources and personal experiences inform this contribution, even if they are not mentioned here. Also needless to say, one's own subjectivities may arise - even if an attempt is made towards intersubjecti vity. This article is an attempt to outline and describe the organisations (and where applicable personalities) in an inclusive and descriptive research approach in See Liebenberg (1990), ldeologie in Konjlik, Emmerentia: Taurus Uitgewers; Liebenberg & Van der Merwe (1991), Die Wordingsgeskiedenis van Apartheid, Joernaal vir Eietydse Geskiedenis, vol 16(2): 1-24; Liebenberg (1994), Resistance by the SANNC and the ANC, 1912 - 1960, in Liebenberg et al (Eds.) The Long March: The Story of the Struggle for Liberation in South Africa. -

The Black Sash

THE BLACK SASH THE BLACK SASH MINUTES OF THE NATIONAL CONFERENCE 1990 CONTENTS: Minutes Appendix Appendix 4. Appendix A - Register B - Resolutions, Statements and Proposals C - Miscellaneous issued by the National Executive 5 Long Street Mowbray 7700 MINUTES OF THE BLACK SASH NATIONAL CONFERENCE 1990 - GRAHAMSTOWN SESSION 1: FRIDAY 2 MARCH 1990 14:00 - 16:00 (ROSEMARY VAN WYK SMITH IN THE CHAIR) I. The National President, Mary Burton, welcomed everyone present. 1.2 The Dedication was read by Val Letcher of Albany 1.3 Rosemary van wyk Smith, a National Vice President, took the chair and called upon the conference to observe a minute's silence in memory of all those who have died in police custody and in detention. She also asked the conference to remember Moira Henderson and Netty Davidoff, who were among the first members of the Black Sash and who had both died during 1989. 1.4 Rosemary van wyk Smith welcomed everyone to Grahamstown and expressed the conference's regrets that Ann Colvin and Jillian Nicholson were unable to be present because of illness and that Audrey Coleman was unable to come. All members of conference were asked to introduce themselves and a roll call was held. (See Appendix A - Register for attendance list.) 1.5 Messages had been received from Errol Moorcroft, Jean Sinclair, Ann Burroughs and Zilla Herries-Baird. Messages of greetings were sent to Jean Sinclair, Ray and Jack Simons who would be returning to Cape Town from exile that weekend. A message of support to the family of Anton Lubowski was approved for dispatch in the light of the allegations of the Minister of Defence made under the shelter of parliamentary privilege. -

Trekking Outward

TREKKING OUTWARD A CHRONOLOGY OF MEETINGS BETWEEN SOUTH AFRICANS AND THE ANC IN EXILE 1983–2000 Michael Savage University of Cape Town May 2014 PREFACE In the decade preceding the dramatic February 1990 unbanning of South Africa’s black liberatory movements, many hundreds of concerned South Africans undertook to make contact with exile leaders of these organisations, travelling long distances to hold meetings in Europe or in independent African countries. Some of these “treks”, as they came to be called, were secret while others were highly publicised. The great majority of treks brought together South Africans from within South Africa and exile leaders of the African National Congress, and its close ally the South African Communist Party. Other treks involved meetings with the Pan Africanist Congress, the black consciousness movement, and the remnants of the Non-European Unity Movement in exile. This account focuses solely on the meetings involving the ANC alliance, which after February 1990 played a central role in negotiating with the white government of F.W. de Klerk and his National Party regime to bring about a new democratic order. Without the foundation of understanding established by the treks and thousands of hours of discussion and debate that they entailed, it seems unlikely that South Africa’s transition to democracy could have been as successfully negotiated as it was between 1990 and the first democratic election of April 1994. The following chronology focuses only on the meetings of internally based South Africans with the African National Congress (ANC) when in exile over the period 1983–1990. Well over 1 200 diverse South Africans drawn from a wide range of different groups in the non- governmental sector and cross-cutting political parties, language, educational, religious and community groups went on an outward mission to enter dialogue with the ANC in exile in a search to overcome the escalating conflict inside South Africa. -

PRENEGOTIATION Ln SOUTH AFRICA (1985 -1993) a PHASEOLOGICAL ANALYSIS of the TRANSITIONAL NEGOTIATIONS

PRENEGOTIATION lN SOUTH AFRICA (1985 -1993) A PHASEOLOGICAL ANALYSIS OF THE TRANSITIONAL NEGOTIATIONS BOTHA W. KRUGER Thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts at the University of Stellenbosch. Supervisor: ProfPierre du Toit March 1998 Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za DECLARATION I, the undersigned, hereby declare that the work contained in this thesis is my own original work and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it at any university for a degree. Signature: Date: The fmancial assistance of the Centre for Science Development (HSRC, South Africa) towards this research is hereby acknowledged. Opinions expressed and conclusions arrived at, are those of the author and are not necessarily to be attributed to the Centre for Science Development. Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za OPSOMMING Die opvatting bestaan dat die Suid-Afrikaanse oorgangsonderhandelinge geinisieer is deur gebeurtenisse tydens 1990. Hierdie stuC.:ie betwis so 'n opvatting en argumenteer dat 'n noodsaaklike tydperk van informele onderhandeling voor formele kontak bestaan het. Gedurende die voorafgaande tydperk, wat bekend staan as vooronderhandeling, het lede van die Nasionale Party regering en die African National Congress (ANC) gepoog om kommunikasiekanale daar te stel en sodoende die moontlikheid van 'n onderhandelde skikking te ondersoek. Deur van 'n fase-benadering tot onderhandeling gebruik te maak, analiseer hierdie studie die oorgangstydperk met die doel om die struktuur en funksies van Suid-Afrikaanse vooronderhandelinge te bepaal. Die volgende drie onderhandelingsfases word onderskei: onderhande/ing oor onderhandeling, voorlopige onderhande/ing, en substantiewe onderhandeling. Beide fases een en twee word beskou as deel van vooronderhandeling. -

The Gordian Knot: Apartheid & the Unmaking of the Liberal World Order, 1960-1970

THE GORDIAN KNOT: APARTHEID & THE UNMAKING OF THE LIBERAL WORLD ORDER, 1960-1970 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By Ryan Irwin, B.A., M.A. History ***** The Ohio State University 2010 Dissertation Committee: Professor Peter Hahn Professor Robert McMahon Professor Kevin Boyle Professor Martha van Wyk © 2010 by Ryan Irwin All rights reserved. ABSTRACT This dissertation examines the apartheid debate from an international perspective. Positioned at the methodological intersection of intellectual and diplomatic history, it examines how, where, and why African nationalists, Afrikaner nationalists, and American liberals contested South Africa’s place in the global community in the 1960s. It uses this fight to explore the contradictions of international politics in the decade after second-wave decolonization. The apartheid debate was never at the center of global affairs in this period, but it rallied international opinions in ways that attached particular meanings to concepts of development, order, justice, and freedom. As such, the debate about South Africa provides a microcosm of the larger postcolonial moment, exposing the deep-seated differences between politicians and policymakers in the First and Third Worlds, as well as the paradoxical nature of change in the late twentieth century. This dissertation tells three interlocking stories. First, it charts the rise and fall of African nationalism. For a brief yet important moment in the early and mid-1960s, African nationalists felt genuinely that they could remake global norms in Africa’s image and abolish the ideology of white supremacy through U.N. -

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report: Volume 2

VOLUME TWO Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report The report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission was presented to President Nelson Mandela on 29 October 1998. Archbishop Desmond Tutu Ms Hlengiwe Mkhize Chairperson Dr Alex Boraine Mr Dumisa Ntsebeza Vice-Chairperson Ms Mary Burton Dr Wendy Orr Revd Bongani Finca Adv Denzil Potgieter Ms Sisi Khampepe Dr Fazel Randera Mr Richard Lyster Ms Yasmin Sooka Mr Wynand Malan* Ms Glenda Wildschut Dr Khoza Mgojo * Subject to minority position. See volume 5. Chief Executive Officer: Dr Biki Minyuku I CONTENTS Chapter 1 Chapter 6 National Overview .......................................... 1 Special Investigation The Death of President Samora Machel ................................................ 488 Chapter 2 The State outside Special Investigation South Africa (1960-1990).......................... 42 Helderberg Crash ........................................... 497 Special Investigation Chemical and Biological Warfare........ 504 Chapter 3 The State inside South Africa (1960-1990).......................... 165 Special Investigation Appendix: State Security Forces: Directory Secret State Funding................................... 518 of Organisations and Structures........................ 313 Special Investigation Exhumations....................................................... 537 Chapter 4 The Liberation Movements from 1960 to 1990 ..................................................... 325 Special Investigation Appendix: Organisational structures and The Mandela United -

Inkanyiso OFC 8.1 FM.Fm

21 The suppression of political opposition and the extent of violating civil liberties in the erstwhile Ciskei and Transkei bantustans, 1960-1989 Maxwell Z. Shamase 1 Department of History, University of Zululand [email protected] This paper aims at interrogating the nature of political suppression and the extent to which civil liberties were violated in the erstwhile Ciskei and Transkei. Whatever the South African government's reasons, publicly stated or hidden, for encouraging bantustan independence, by the time of Ciskei's independence ceremonies in December 1981 it was clear that the bantustans were also to be used as a more brutal instrument for suppressing opposition. Both Transkei and Ciskei used additional emergency-style laws to silence opposition in the run-up to both self- government and later independence. By the mid-1980s a clear pattern of brutal suppression of opposition had emerged in both bantustans, with South Africa frequently washing its hands of the situation on the grounds that these were 'independent' countries. Both bantustans borrowed repressive South African legislation initially and, in addition, backed this up with emergency-style regulations passed with South African assistance before independence (Proclamation 400 and 413 in Transkei which operated from 1960 until 1977, and Proclamation R252 in Ciskei which operated from 1977 until 1982). The emergency Proclamations 400, 413 and R252 appear to have been retained in the Transkei case and introduced in the Ciskei in order to suppress legal opposition at the time of attainment of self-government status. Police in the bantustans (initially SAP and later the Transkei and Ciskei Police) targeted political opponents rather than criminals, as the SAP did in South Africa. -

Mirror, Mediator, and Prophet: the Music Indaba of Late-Apartheid South Africa

VOL. 42, NO. 1 ETHNOMUSICOLOGY WINTER 1998 Mirror, Mediator, and Prophet: The Music Indaba of Late-Apartheid South Africa INGRID BIANCA BYERLY DUKE UNIVERSITY his article explores a movement of creative initiative, from 1960 to T 1990, that greatly influenced the course of history in South Africa.1 It is a movement which holds a deep affiliation for me, not merely through an extended submersion and profound interest in it, but also because of the co-incidence of its timing with my life in South Africa. On the fateful day of the bloody Sharpeville march on 21 March 1960, I was celebrating my first birthday in a peaceful coastal town in the Cape Province. Three decades later, on the weekend of Nelson Mandela’s release from prison in February 1990, I was preparing to leave for the United States to further my studies in the social theories that lay at the base of the remarkable musical movement that had long engaged me. This musical phenomenon therefore spans exactly the three decades of my early life in South Africa. I feel privi- leged to have experienced its development—not only through growing up in the center of this musical moment, but particularly through a deepen- ing interest, and consequently, an active participation in its peak during the mid-1980s. I call this movement the Music Indaba, for it involved all sec- tors of the complex South African society, and provided a leading site within which the dilemmas of the late-apartheid era could be explored and re- solved, particularly issues concerning identity, communication and social change. -

I.D.A.Fnews Notes

i.d. a.fnews notes Published by the United States Committee of the International Defense and Aid Fund for Southern Africa p.o. Box 17, Cambridge, MA 02138 February 1986, Issue No, 25 Telephone (617) 491-8343 MacNeil: Mr. Parks, would you confirm that the violence does continue even though the cameras are not there? . Ignorance is Bliss? Parks: In October, before they placed the restrictions on the press, I took Shortly after a meeting ofbankers in London agreed to reschedule South Africa's a look atthe -where people were dying, the circumstances. And the best enormous foreign debt, an editorial on the government-controlled Radio South I could determine was that in at least 80% of the deaths up to that time, Africa thankfully attributed the bankers' understanding of the South African situation to the government's news blackout, which had done much to eliminate (continued on page 2) the images ofprotest and violence in the news which had earlier "misinformed" the bankers. As a comment on this, we reprint the following S/(cerpts from the MacNeil-Lehrer NewsHour broadcast on National Public TV on December 19, 1985. The interviewer is Robert MacNeil. New Leaders in South Africa MacNeil: Today a South African court charged a British TV crew with Some observers have attached great significance to the meeting that took inciting a riot by filming a clash between blacks and police near Pretoria. place in South Africa on December 28, at which the National Parents' The camera crew denied the charge and was released on bail after hav Crisis Committee was formed.