Microsoft Word Viewer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nelson-Mandelas-Legacy.Pdf

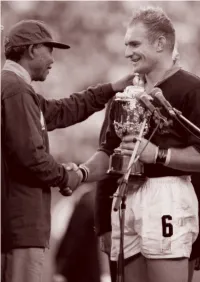

Nelson Mandela’s Legacy What the World Must Learn from One of Our Greatest Leaders By John Carlin ver since Nelson Mandela became president of South Africa after winning his Ecountry’s fi rst democratic elections in April 1994, the national anthem has consisted of two songs spliced—not particularly mellifl uously—together. One is “Nkosi Sikelel’ iAfrika,” or “God Bless Africa,” sung at black protest ral- lies during the forty-six years between the rise and fall of apartheid. The other is “Die Stem,” (“The Call”), the old white anthem, a celebration of the European settlers’ conquest of Africa’s southern tip. It was Mandela’s idea to juxtapose the two, his purpose being to forge from the rival tunes’ discordant notes a powerfully symbolic message of national harmony. Not everyone in Mandela’s party, the African National Congress, was con- vinced when he fi rst proposed the plan. In fact, the entirety of the ANC’s national executive committee initially pushed to scrap “Die Stem” and replace it with “Nkosi Sikelel’ iAfrika.” Mandela won the argument by doing what defi ned his leadership: reconciling generosity with pragmatism, fi nding common ground between humanity’s higher values and the politician’s aspiration to power. The chief task the ANC would have upon taking over government, Mandela reminded his colleagues at the meeting, would be to cement the foundations of the hard-won new democracy. The main threat to peace and stability came from right-wing terrorism. The way to deprive the extremists of popular sup- port, and therefore to disarm them, was by convincing the white population as a whole President Nelson Mandela and that they belonged fully in the ‘new South Francois Pienaar, captain of the Africa,’ that a black-led government would South African Springbok rugby not treat them the way previous white rulers team, after the Rugby World Cup had treated blacks. -

Before March 21,1960 Sharpevilie Had

An MK Combatant Speaks on Sharpe ville -Before March 21,1960 Sharpevilie had not much significance, except that it is a small ghetto where Africans daily struggle for survival a; few kilometres from Vereeniging. True, the sharp contrast between the squalor of Sharpevilie and the gli tter of Vereeniging expressive of the deejv-rooted inequality between oppressive and exploitative apartheid rulers on the one hand, and the millions of their victims on the other, between black and white " throughout the country, still exists undisturbed. But over the past 22 years Sharpevilie has acqui red great significance. ' - - To the Bothas and Treurnichts, the Qppenheimers and Louis Luyts the very mention of the word 'Sharpevilie1 strikes a note of uncertainty about the future of their decadent system of fascist colonial domination and exploitation - the false and sinister pride they once deprived from their massacre of our people at Sharpevilie and ^anga in defence of apartheid i s fast diminishing. To oppressed but fighting people Sharpevilie calls to mind all the grisly atrocities perpetrated by these racist colonialists since they set foot - on our land; and reminds us of all our martyrs and heroes who have laid down their lives in the name of our just cause of liberation. Shaav peville sharpens our hatred for apartheid, this system which has brought only hunger, disease, broken families, ignorance, insecurity and death to our peoples in South Africa and Namibia and a constant threat to the peace-loving peoples' of Angola, Mozambique, Lesotho, Botswana, Swaziland, Zambia, Zimbabwe and Seychelles. To the international democratic community Sharpen ville emphasises the importance of unity in isolating-the apart heid regime in the economic, political, military, cultural and all other spheres." Sharpevilie must draw our attention to the urgent need to destroy apartheid fascism" and build a new non- rafeiSl,: democratic and 'peaceful South Africa of the Preeaom Charter. -

South Africa

Safrica Page 1 of 42 Recent Reports Support HRW About HRW Site Map May 1995 Vol. 7, No.3 SOUTH AFRICA THREATS TO A NEW DEMOCRACY Continuing Violence in KwaZulu-Natal INTRODUCTION For the last decade South Africa's KwaZulu-Natal region has been troubled by political violence. This conflict escalated during the four years of negotiations for a transition to democratic rule, and reached the status of a virtual civil war in the last months before the national elections of April 1994, significantly disrupting the election process. Although the first year of democratic government in South Africa has led to a decrease in the monthly death toll, the figures remain high enough to threaten the process of national reconstruction. In particular, violence may prevent the establishment of democratic local government structures in KwaZulu-Natal following further elections scheduled to be held on November 1, 1995. The basis of this violence remains the conflict between the African National Congress (ANC), now the leading party in the Government of National Unity, and the Inkatha Freedom Party (IFP), the majority party within the new region of KwaZulu-Natal that replaced the former white province of Natal and the black homeland of KwaZulu. Although the IFP abandoned a boycott of the negotiations process and election campaign in order to participate in the April 1994 poll, following last minute concessions to its position, neither this decision nor the election itself finally resolved the points at issue. While the ANC has argued during the year since the election that the final constitutional arrangements for South Africa should include a relatively centralized government and the introduction of elected government structures at all levels, the IFP has maintained instead that South Africa's regions should form a federal system, and that the colonial tribal government structures should remain in place in the former homelands. -

SHARPEVILLE and AFTER SUPPRESSION and LIBERATION

SHARPEVILLE AND AFTER SUPPRESSION and LIBERATION in SOUTHERN AFRICA sharpeville march 21,1960 sixty nine Africans shot dead by policep hundreds injured and thousands arrested. SHARPEVILLE. Symbol of the violence and racism of white South Africa. Symbol of white destruction of non-violent African protest. Symbol of the violent truth. inside south africa In the Republic of South Africa the white 19 per cent of the population has total political and economic control over the 81 per cent African, Asian and "Colored" (people of mixed racial ancestry) majority. They also control 100 per cent of the land, 87 per cent of which is to be occupied by whites only. The remaining land (con taining virtually none of the country's natural resources) is "reserved* for the 13 million Africans who comprise a cheep labor pool for white-owned industry and agriculture. The average per capita income of Africans is only 10 per cent that of whites in South Africa. One main pillar of this system of apertheid (the forced in equality of racial groups) is the PASS LAWS. Every African is required to carry a pass (reference) book in order to work, move about, or live anywhere. Failure to produce a pass on demand is a criminal offence which results in imprisonment and fines for half a million Africans every year. It is the pass system which enables the white government to control the black majority with police state efficiency. To Africans the pass is a *badge of slavery." the sharpeville massacre The pass laws became the fo cus of protest in 1960 for a newly formed African nationalist party, the Pan Africanist Congress (PAC), an offshoot of the older African National Congress (ANC). -

PRENEGOTIATION Ln SOUTH AFRICA (1985 -1993) a PHASEOLOGICAL ANALYSIS of the TRANSITIONAL NEGOTIATIONS

PRENEGOTIATION lN SOUTH AFRICA (1985 -1993) A PHASEOLOGICAL ANALYSIS OF THE TRANSITIONAL NEGOTIATIONS BOTHA W. KRUGER Thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts at the University of Stellenbosch. Supervisor: ProfPierre du Toit March 1998 Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za DECLARATION I, the undersigned, hereby declare that the work contained in this thesis is my own original work and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it at any university for a degree. Signature: Date: The fmancial assistance of the Centre for Science Development (HSRC, South Africa) towards this research is hereby acknowledged. Opinions expressed and conclusions arrived at, are those of the author and are not necessarily to be attributed to the Centre for Science Development. Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za OPSOMMING Die opvatting bestaan dat die Suid-Afrikaanse oorgangsonderhandelinge geinisieer is deur gebeurtenisse tydens 1990. Hierdie stuC.:ie betwis so 'n opvatting en argumenteer dat 'n noodsaaklike tydperk van informele onderhandeling voor formele kontak bestaan het. Gedurende die voorafgaande tydperk, wat bekend staan as vooronderhandeling, het lede van die Nasionale Party regering en die African National Congress (ANC) gepoog om kommunikasiekanale daar te stel en sodoende die moontlikheid van 'n onderhandelde skikking te ondersoek. Deur van 'n fase-benadering tot onderhandeling gebruik te maak, analiseer hierdie studie die oorgangstydperk met die doel om die struktuur en funksies van Suid-Afrikaanse vooronderhandelinge te bepaal. Die volgende drie onderhandelingsfases word onderskei: onderhande/ing oor onderhandeling, voorlopige onderhande/ing, en substantiewe onderhandeling. Beide fases een en twee word beskou as deel van vooronderhandeling. -

South Africaâ•Žs Post-Apartheid Foreign Policy Towards Africa

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Iowa Research Online Electronic Journal of Africana Bibliography Volume 6 South Africa’s Post-Apartheid Foreign Policy Article 1 Towards Africa 2-6-2001 South Africa’s Post-Apartheid Foreign Policy Towards Africa Roger Pfister Swiss Federal Institute of Technology ETH, Zurich Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.uiowa.edu/ejab Part of the African History Commons, and the African Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation Pfister, Roger (2001) "South Africa’s Post-Apartheid Foreign Policy Towards Africa," Electronic Journal of Africana Bibliography: Vol. 6 , Article 1. https://doi.org/10.17077/1092-9576.1003 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Iowa Research Online. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Journal of Africana Bibliography by an authorized administrator of Iowa Research Online. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Volume 6 (2000) South Africa’s Post-Apartheid Foreign Policy Towards Africa Roger Pfister, Centre for International Studies, Swiss Federal Institute of Technology ETH, Zurich Preface 1. Introduction Two principal factors have shaped South Africa’s post-apartheid foreign policy towards Africa. First, the termination of apartheid in 1994 allowed South Africa, for the first time in the country’s history, to establish and maintain contacts with African states on equal terms. Second, the end of the Cold War at the end of the 1980s led to a retreat of the West from Africa, particularly in the economic sphere. Consequently, closer cooperation among all African states has become more pertinent to finding African solutions to African problems. -

Trc-Media-Sapa-2000.Pdf

GRAHAMSTOWN Jan 5 Sapa THREE OF DE KOCK'S CO-ACCUSED TO CHALLENGE TRC DECISION Three former security branch policemen plan to challenge the Truth and Reconciliation Commission's decision to refuse them and seven of their former colleagues, including Eugene de Kock, amnesty for the 1989 murder of four policemen. De Kock, Daniel Snyman, Nicholaas Janse Van Rensburg, Gerhardus Lotz, Jacobus Kok, Wybrand Du Toit, Nicolaas Vermeulen, Marthinus Ras and Gideon Nieuwoudt admitted responsibility for the massive car bomb which claimed the lives of Warrant Officer Mbalala Mgoduka, Sergeant Amos Faku, Sergeant Desmond Mpipa and an Askari named Xolile Shepherd Sekati. The four men died when a bomb hidden in the police car they were travelling in was detonated in a deserted area in Motherwell, Port Elizabeth, late at night in December 1989. Lawyer for Nieuwoudt, Lotz and Van Rensburg, Francois van der Merwe said he would shortly give notice to the TRC of their intention to take on review the decision to refuse the nine men amnesty. He said the judgment would be taken on review in its entirety, and if it was overturned by the court, the TRC would once again have to apply its mind to the matter in respect of all nine applicants. The applicants had been "unfairly treated", he said and the judges had failed to properly apply their mind to the matter. The amnesty decision was split, with Acting Judge Denzil Potgieter and Judge Bernard Ngoepe finding in the majority decision that the nine men did not qualify for amnesty as the act was not associated with a political objective and was not directed against members of the ANC or other liberation movements. -

The Burundi Peace Process

ISS MONOGRAPH 171 ISS Head Offi ce Block D, Brooklyn Court 361 Veale Street New Muckleneuk, Pretoria, South Africa Tel: +27 12 346-9500 Fax: +27 12 346-9570 E-mail: [email protected] Th e Burundi ISS Addis Ababa Offi ce 1st Floor, Ki-Ab Building Alexander Pushkin Street PEACE CONDITIONAL TO CIVIL WAR FROM PROCESS: THE BURUNDI PEACE Peace Process Pushkin Square, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia Th is monograph focuses on the role peacekeeping Tel: +251 11 372-1154/5/6 Fax: +251 11 372-5954 missions played in the Burundi peace process and E-mail: [email protected] From civil war to conditional peace in ensuring that agreements signed by parties to ISS Cape Town Offi ce the confl ict were adhered to and implemented. 2nd Floor, Armoury Building, Buchanan Square An AU peace mission followed by a UN 160 Sir Lowry Road, Woodstock, South Africa Tel: +27 21 461-7211 Fax: +27 21 461-7213 mission replaced the initial SA Protection Force. E-mail: [email protected] Because of the non-completion of the peace ISS Nairobi Offi ce process and the return of the PALIPEHUTU- Braeside Gardens, Off Muthangari Road FNL to Burundi, the UN Security Council Lavington, Nairobi, Kenya Tel: +254 20 386-1625 Fax: +254 20 386-1639 approved the redeployment of an AU mission to E-mail: [email protected] oversee the completion of the demobilisation of ISS Pretoria Offi ce these rebel forces by December 2008. Block C, Brooklyn Court C On 18 April 2009, at a ceremony to mark the 361 Veale Street ON beginning of the demobilisation of thousands New Muckleneuk, Pretoria, South Africa DI Tel: +27 12 346-9500 Fax: +27 12 460-0998 TI of PALIPEHUTU-FNL combatants, Agathon E-mail: [email protected] ON Rwasa, leader of PALIPEHUTU-FNL, gave up AL www.issafrica.org P his AK-47 and military uniform. -

Struggle for Liberation in South Africa and International Solidarity A

STRUGGLE FOR LIBERATION IN SOUTH AFRICA AND INTERNATIONAL SOLIDARITY A Selection of Papers Published by the United Nations Centre against Apartheid Edited by E. S. Reddy Senior Fellow, United Nations Institute for Training and Research STERLING PUBLISHERS PRIVATE LIMITED NEW DELHI 1992 INTRODUCTION One of the essential contributions of the United Nations in the international campaign against apartheid in South Africa has been the preparation and dissemination of objective information on the inhumanity of apartheid, the long struggle of the oppressed people for their legitimate rights and the development of the international campaign against apartheid. For this purpose, the United Nations established a Unit on Apartheid in 1967, renamed Centre against Apartheid in 1976. I have had the privilege of directing the Unit and the Centre until my retirement from the United Nations Secretariat at the beginning of 1985. The Unit on Apartheid and the Centre against Apartheid obtained papers from leaders of the liberation movement and scholars, as well as eminent public figures associated with the international anti-apartheid movements. A selection of these papers are reproduced in this volume, especially those dealing with episodes in the struggle for liberation; the role of women, students, churches and the anti-apartheid movements in the resistance to racism; and the wider significance of the struggle in South Africa. I hope that these papers will be of value to scholars interested in the history of the liberation movement in South Africa and the evolution of United Nations as a force against racism. The papers were prepared at various times, mostly by leaders and active participants in the struggle, and should be seen in their context. -

We Were Cut Off from the Comprehension of Our Surroundings

Black Peril, White Fear – Representations of Violence and Race in South Africa’s English Press, 1976-2002, and Their Influence on Public Opinion Inauguraldissertation zur Erlangung der Doktorwürde der Philosophischen Fakultät der Universität zu Köln vorgelegt von Christine Ullmann Institut für Völkerkunde Universität zu Köln Köln, Mai 2005 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The work presented here is the result of years of research, writing, re-writing and editing. It was a long time in the making, and may not have been completed at all had it not been for the support of a great number of people, all of whom have my deep appreciation. In particular, I would like to thank Prof. Dr. Michael Bollig, Prof. Dr. Richard Janney, Dr. Melanie Moll, Professor Keyan Tomaselli, Professor Ruth Teer-Tomaselli, and Prof. Dr. Teun A. van Dijk for their help, encouragement, and constructive criticism. My special thanks to Dr Petr Skalník for his unflinching support and encouraging supervision, and to Mark Loftus for his proof-reading and help with all language issues. I am equally grateful to all who welcomed me to South Africa and dedicated their time, knowledge and effort to helping me. The warmth and support I received was incredible. Special thanks to the Burch family for their help settling in, and my dear friend in George for showing me the nature of determination. Finally, without the unstinting support of my two colleagues, Angelika Kitzmantel and Silke Olig, and the moral and financial backing of my family, I would surely have despaired. Thank you all for being there for me. We were cut off from the comprehension of our surroundings; we glided past like phantoms, wondering and secretly appalled, as sane men would be before an enthusiastic outbreak in a madhouse. -

The Rollback of South Africa's Chemical and Biological Warfare

The Rollback of South Africa’s Chemical and Biological Warfare Program Stephen Burgess and Helen Purkitt US Air Force Counterproliferation Center Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama THE ROLLBACK OF SOUTH AFRICA’S CHEMICAL AND BIOLOGICAL WARFARE PROGRAM by Dr. Stephen F. Burgess and Dr. Helen E. Purkitt USAF Counterproliferation Center Air War College Air University Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama The Rollback of South Africa’s Chemical and Biological Warfare Program Dr. Stephen F. Burgess and Dr. Helen E. Purkitt April 2001 USAF Counterproliferation Center Air War College Air University Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama 36112-6427 The internet address for the USAF Counterproliferation Center is: http://www.au.af.mil/au/awc/awcgate/awc-cps.htm . Contents Page Disclaimer.....................................................................................................i The Authors ............................................................................................... iii Acknowledgments .......................................................................................v Chronology ................................................................................................vii I. Introduction .............................................................................................1 II. The Origins of the Chemical and Biological Warfare Program.............3 III. Project Coast, 1981-1993....................................................................17 IV. Rollback of Project Coast, 1988-1994................................................39 -

The Foreign Policies of Mandela and Mbeki: a Clear Case of Idealism Vs Realism ?

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Stellenbosch University SUNScholar Repository THE FOREIGN POLICIES OF MANDELA AND MBEKI: A CLEAR CASE OF IDEALISM VS REALISM ? by CHRISTIAN YOULA Thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts (International Studies) at Stellenbosch University Department of Political Science Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences Supervisor: Dr Karen Smith March 2009 Declaration By submitting this thesis electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own, original work, that I am the owner of the copyright thereof and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. Date: 28 February 2009 Copyright © 2009 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved i Abstract After 1994, South African foreign policymakers faced the challenge of reintegrating a country, isolated for many years as a result of the previous government’s apartheid policies, into the international system. In the process of transforming South Africa's foreign identity from a pariah state to a respected international player, some commentators contend that presidents Mandela and Mbeki were informed by two contrasting theories of International Relations (IR), namely, idealism and realism, respectively. In light of the above-stated popular assumptions and interpretations of the foreign policies of Presidents Mandela and Mbeki, this study is motivated by the primary aim to investigate the classification of their foreign policy within the broader framework of IR theory. This is done by sketching a brief overview of the IR theories of idealism, realism and constructivism, followed by an analysis of the foreign policies of these two statesmen in order to identify some of the principles that underpin them.