South Africa's Relations with Iraq

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

South Africaâ•Žs Post-Apartheid Foreign Policy Towards Africa

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Iowa Research Online Electronic Journal of Africana Bibliography Volume 6 South Africa’s Post-Apartheid Foreign Policy Article 1 Towards Africa 2-6-2001 South Africa’s Post-Apartheid Foreign Policy Towards Africa Roger Pfister Swiss Federal Institute of Technology ETH, Zurich Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.uiowa.edu/ejab Part of the African History Commons, and the African Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation Pfister, Roger (2001) "South Africa’s Post-Apartheid Foreign Policy Towards Africa," Electronic Journal of Africana Bibliography: Vol. 6 , Article 1. https://doi.org/10.17077/1092-9576.1003 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Iowa Research Online. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Journal of Africana Bibliography by an authorized administrator of Iowa Research Online. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Volume 6 (2000) South Africa’s Post-Apartheid Foreign Policy Towards Africa Roger Pfister, Centre for International Studies, Swiss Federal Institute of Technology ETH, Zurich Preface 1. Introduction Two principal factors have shaped South Africa’s post-apartheid foreign policy towards Africa. First, the termination of apartheid in 1994 allowed South Africa, for the first time in the country’s history, to establish and maintain contacts with African states on equal terms. Second, the end of the Cold War at the end of the 1980s led to a retreat of the West from Africa, particularly in the economic sphere. Consequently, closer cooperation among all African states has become more pertinent to finding African solutions to African problems. -

I.D.A.Fnews Notes

i.d. a.fnews notes Published by the United States Committee of the International Defense and Aid Fund for Southern Africa p.o. Box 17, Cambridge, MA 02138 February 1986, Issue No, 25 Telephone (617) 491-8343 MacNeil: Mr. Parks, would you confirm that the violence does continue even though the cameras are not there? . Ignorance is Bliss? Parks: In October, before they placed the restrictions on the press, I took Shortly after a meeting ofbankers in London agreed to reschedule South Africa's a look atthe -where people were dying, the circumstances. And the best enormous foreign debt, an editorial on the government-controlled Radio South I could determine was that in at least 80% of the deaths up to that time, Africa thankfully attributed the bankers' understanding of the South African situation to the government's news blackout, which had done much to eliminate (continued on page 2) the images ofprotest and violence in the news which had earlier "misinformed" the bankers. As a comment on this, we reprint the following S/(cerpts from the MacNeil-Lehrer NewsHour broadcast on National Public TV on December 19, 1985. The interviewer is Robert MacNeil. New Leaders in South Africa MacNeil: Today a South African court charged a British TV crew with Some observers have attached great significance to the meeting that took inciting a riot by filming a clash between blacks and police near Pretoria. place in South Africa on December 28, at which the National Parents' The camera crew denied the charge and was released on bail after hav Crisis Committee was formed. -

The Apartheid Divide

PUNC XI: EYE OF THE STORM 2018 The Apartheid Divide Sponsored by: Presented by: Table of Contents Letter from the Crisis Director Page 2 Letter from the Chair Page 4 Committee History Page 6 Delegate Positions Page 8 Committee Structure Page 11 1 Letter From the Crisis Director Hello, and welcome to The Apartheid Divide! My name is Allison Brown and I will be your Crisis Director for this committee. I am a sophomore majoring in Biomedical Engineering with a focus in Biochemicals. This is my second time being a Crisis Director, and my fourth time staffing a conference. I have been participating in Model United Nations conferences since high school and have continued doing so ever since I arrived at Penn State. Participating in the Penn State International Affairs and Debate Association has helped to shape my college experience. Even though I am an engineering major, I am passionate about current events, politics, and international relations. This club has allowed me to keep up with my passion, while also keeping with my other passion; biology. I really enjoy being a Crisis Director and I am so excited to do it again! This committee is going to focus on a very serious topic from our world’s past; Apartheid. The members of the Presidents Council during this time were quite the collection of people. It is important during the course of this conference that you remember to be respectful to other delegates (both in and out of character) and to be thoughtful before making decisions or speeches. If you ever feel uncomfortable, please inform myself or the chair, Sneha, and we will address the issue. -

The Burundi Peace Process

ISS MONOGRAPH 171 ISS Head Offi ce Block D, Brooklyn Court 361 Veale Street New Muckleneuk, Pretoria, South Africa Tel: +27 12 346-9500 Fax: +27 12 346-9570 E-mail: [email protected] Th e Burundi ISS Addis Ababa Offi ce 1st Floor, Ki-Ab Building Alexander Pushkin Street PEACE CONDITIONAL TO CIVIL WAR FROM PROCESS: THE BURUNDI PEACE Peace Process Pushkin Square, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia Th is monograph focuses on the role peacekeeping Tel: +251 11 372-1154/5/6 Fax: +251 11 372-5954 missions played in the Burundi peace process and E-mail: [email protected] From civil war to conditional peace in ensuring that agreements signed by parties to ISS Cape Town Offi ce the confl ict were adhered to and implemented. 2nd Floor, Armoury Building, Buchanan Square An AU peace mission followed by a UN 160 Sir Lowry Road, Woodstock, South Africa Tel: +27 21 461-7211 Fax: +27 21 461-7213 mission replaced the initial SA Protection Force. E-mail: [email protected] Because of the non-completion of the peace ISS Nairobi Offi ce process and the return of the PALIPEHUTU- Braeside Gardens, Off Muthangari Road FNL to Burundi, the UN Security Council Lavington, Nairobi, Kenya Tel: +254 20 386-1625 Fax: +254 20 386-1639 approved the redeployment of an AU mission to E-mail: [email protected] oversee the completion of the demobilisation of ISS Pretoria Offi ce these rebel forces by December 2008. Block C, Brooklyn Court C On 18 April 2009, at a ceremony to mark the 361 Veale Street ON beginning of the demobilisation of thousands New Muckleneuk, Pretoria, South Africa DI Tel: +27 12 346-9500 Fax: +27 12 460-0998 TI of PALIPEHUTU-FNL combatants, Agathon E-mail: [email protected] ON Rwasa, leader of PALIPEHUTU-FNL, gave up AL www.issafrica.org P his AK-47 and military uniform. -

Why South Africa Gave up the Bomb and the Implications for Nuclear Nonproliferation Policy 1

White Elephants:Why South Africa Gave Up the Bomb and the Implications for Nuclear Nonproliferation Policy 1 WHITE ELEPHANTS: WHY SOUTH AFRICA GAVE UP THE BOMB AND THE IMPLICATIONS FOR NUCLEAR NONPROLIFERATION POLICY Maria Babbage This article examines why the South African government chose to dismantle its indigenous nuclear arsenal in 1993. It consid- ers three competing explanations for South African nuclear disarmament: the realist argument, which suggests that the country responded to a reduction in the perceived threat to its security; the idealist argument, which sees the move as a signal to Western liberal democratic states that South Africa wished to join their ranks; and a more pragmatic argument—that the apartheid government scrapped the program out of fear that its nuclear weapons would be misused by a black-major- ity government. The article argues that the third explanation offers the most plausible rationale for South Africa’s decision to denuclearize. Indeed, it contends that the apartheid South African government destroyed its indigenous nuclear arsenal and acceded to the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty to “tie the hands” of the future ANC government, thereby preventing any potential misuse of the technology, whether through its proliferation or use against a target. Maria Babbage is a Master of Arts candidate at the Norman Paterson School of Inter- national Affairs, Carleton University ([email protected]). Journal of Public and International Affairs, Volume 15/Spring 2004 Copyright © 2004, the Trustees of Princeton University 7 http://www.princeton.edu/~jpia White Elephants:Why South Africa Gave Up 2 Maria Babbage the Bomb and the Implications for Nuclear Nonproliferation Policy 3 In March 1993, South African President F.W. -

The Foreign Policies of Mandela and Mbeki: a Clear Case of Idealism Vs Realism ?

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Stellenbosch University SUNScholar Repository THE FOREIGN POLICIES OF MANDELA AND MBEKI: A CLEAR CASE OF IDEALISM VS REALISM ? by CHRISTIAN YOULA Thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts (International Studies) at Stellenbosch University Department of Political Science Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences Supervisor: Dr Karen Smith March 2009 Declaration By submitting this thesis electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own, original work, that I am the owner of the copyright thereof and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. Date: 28 February 2009 Copyright © 2009 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved i Abstract After 1994, South African foreign policymakers faced the challenge of reintegrating a country, isolated for many years as a result of the previous government’s apartheid policies, into the international system. In the process of transforming South Africa's foreign identity from a pariah state to a respected international player, some commentators contend that presidents Mandela and Mbeki were informed by two contrasting theories of International Relations (IR), namely, idealism and realism, respectively. In light of the above-stated popular assumptions and interpretations of the foreign policies of Presidents Mandela and Mbeki, this study is motivated by the primary aim to investigate the classification of their foreign policy within the broader framework of IR theory. This is done by sketching a brief overview of the IR theories of idealism, realism and constructivism, followed by an analysis of the foreign policies of these two statesmen in order to identify some of the principles that underpin them. -

South Africa After Apartheid: a Whole New Ball Game, with Labor on the Team

r , * ',-,- - i i-.-- : ii ii i -ii,,,c - -. i - 198 Broadway * New York, N.Y. 10038 e (212) 962-1210 Tilden J. LeMelle, Chairman Jennifer Davis, Executive Director MEMORANDUM TO: Key Labor Contacts FROM: Mike Fleshman, Labor Desk Coordinator DATE: June 7, 1994 South Africa After Apartheid: A Whole New Ball Game, With Labor On The Team Friends, The victory parties are finally over and, in the wake of Nelson Mandela's landslide election as South Africa's first-ever Black President, South African workers are returning to their jobs and to the enormous challenges that lie ahead. For the 1.2 million-member Congress of South African Trade Unions (COSATU), whose support for Mandela's ANC was critical to the movement's runaway 62.5 percent victory, the end of apartheid brings new opportunities for South African workers, but also some new problems. One result of the ANC victory is the presence of key labor leaders in the new government. Two high ranking unionists, former COSATU General Secretary Jay Naidoo, and former Assistant General Secretary Sydney Mufamadi, were named to cabinet posts -- Mufamadi as Minister of Safety and Security in charge of the police, and Naidoo as Minister Without Portfolio, tasked with implementing the ANC/COSATU blueprint for social change, the national Reconstruction and Development Program (RDP). Former National Union of Metalworkers of South Africa (NUMSA) economist Alec Erwin was named Deputy Minister for Finance. Former Mineworkers head Cyril Ramaphosa, elected General Secretary of the ANC in 1991, will exert great influence on the shape of the permanent new constitution as the chair of the parliamentary constitution-writing body. -

South Africa Tackles Global Apartheid: Is the Reform Strategy Working? - South Atlantic Quarterly, 103, 4, 2004, Pp.819-841

critical essays on South African sub-imperialism regional dominance and global deputy-sheriff duty in the run-up to the March 2013 BRICS summit by Patrick Bond Neoliberalism in SubSaharan Africa: From structural adjustment to the New Partnership for Africas Development – in Alfredo Saad-Filho and Deborah Johnstone (Eds), Neoliberalism: A Critical Reader, London, Pluto Press, 2005, pp.230-236. US empire and South African subimperialism - in Leo Panitch and Colin Leys (Eds), Socialist Register 2005: The Empire Reloaded, London, Merlin Press, 2004, pp.125- 144. Talk left, walk right: Rhetoric and reality in the New South Africa – Global Dialogue, 2004, 6, 4, pp.127-140. Bankrupt Africa: Imperialism, subimperialism and financial politics - Historical Materialism, 12, 4, 2004, pp.145-172. The ANCs “left turn” and South African subimperialism: Ideology, geopolitics and capital accumulation - Review of African Political Economy, 102, September 2004, pp.595-611. South Africa tackles Global Apartheid: Is the reform strategy working? - South Atlantic Quarterly, 103, 4, 2004, pp.819-841. Removing Neocolonialisms APRM Mask: A critique of the African Peer Review Mechanism – Review of African Political Economy, 36, 122, December 2009, pp. 595-603. South African imperial supremacy - Le Monde Diplomatique, Paris, May 2010. South Africas dangerously unsafe financial intercourse - Counterpunch, 24 April 2012. Financialization, corporate power and South African subimperialism - in Ronald W. Cox, ed., Corporate Power in American Foreign Policy, London, Routledge Press, 2012, pp.114-132. Which Africans will Obama whack next? – forthcoming in Monthly Review, January 2012. 2 Neoliberalism in SubSaharan Africa: From structural adjustment to the New Partnership for Africa’s Development Introduction Distorted forms of capital accumulation and class formation associated with neoliberalism continue to amplify Africa’s crisis of combined and uneven development. -

The Rise of the South African Security Establishment an Essay on the Changing Locus of State Power

BRADLOW SERIE£ r NUMBER ONE - ft \\ \ "*\\ The Rise of the South African Security Establishment An Essay on the Changing Locus of State Power Kenneth W. Grundy THl U- -" , ., • -* -, THE SOUTH AFRICAN INSTITUTE OF INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS The Rise of the South African Security Establishment An Essay on the Changing Locus of State Power Kenneth W, Grundy THE SOUTH AFRICAN INSTITUTE OF INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS August 1983 BRADLOW PAPER NO. 1 THE BRADLOW FELLOWSHIP The Bradlow Fellowship is awarded from a grant made to the South African Institute of In- ternational Affairs from the funds of the Estate late H. Bradlow. Kenneth W. Grundy is Professor of Political Science at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, Ohio. Professor Grundy is considered an authority on the role of the military in African affairs. In 1982, Professor Grundy was elected the first Bradlow Fellow at the South African Institute of International Affairs. Founded in Cape Town in 1934, the South African Institute of International Affairs is a fully independent national organisation whose aims are to promote a wider and more informed understanding of international issues — particularly those affecting South Africa — through objective research, study, the dissemination of information and communication between people concerned with these issues, within and outside South Africa. The Institute is privately funded by its corporate and individual members. Although Jan Smuts House is on the Witwatersrand University campus, the Institute is administratively and financially independent. It does not receive government funds from any source. Membership is open to all, irrespective of race, creed or sex, who have a serious interest in international affairs. -

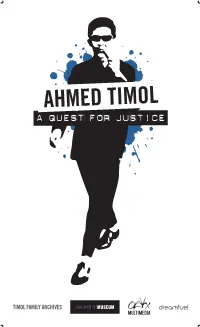

Ahmed Timol Was the First Detainee to Die at John Vorster Square

“He hung from a piece of soap while washing…” In Detention, Chris van Wyk, 1979 On 23 August 1968, Prime Minister Vorster opened a new police station in Johannesburg known as John Vorster Square. Police described it as a state of the art facility, where incidents such as the 1964 “suicide” of political detainee, Suliman “Babla” Saloojee, could be avoided. On 9 September 1964 Saloojee fell or was thrown from the 7th floor of the old Gray’s Building, the Special Branch’s then-headquarters in Johannesburg. Security police routinely tortured political detainees on the 9th and 10th floors of John Vorster Square. Between 1971 and 1990 a number of political detainees died there. Ahmed Timol was the first detainee to die at John Vorster Square. 27 October 1971 – Ahmed Timol 11 December 1976 – Mlungisi Tshazibane 15 February 1977 – Matthews Marwale Mabelane 5 February 1982 – Neil Aggett 8 August 1982 – Ernest Moabi Dipale 30 January 1990 – Clayton Sizwe Sithole 1 Rapport, 31 October 1971 Courtesy of the Timol Family Courtesy of the Timol A FAMILY ON THE MOVE Haji Yusuf Ahmed Timol, Ahmed Timol’s father, was The young Ahmed suffered from bronchitis and born in Kholvad, India, and travelled to South Africa in became a patient of Dr Yusuf Dadoo, who was the 1918. In 1933 he married Hawa Ismail Dindar. chairman of the South African Indian Congress and the South African Communist Party. Ahmed Timol, one of six children, was born in Breyten in the then Transvaal, on 3 November 1941. He and his Dr Dadoo’s broad-mindedness and pursuit of siblings were initially home-schooled because there was non-racialism were to have a major influence on no school for Indian children in Breyten. -

Harmony and Discord in South African Foreign Policy Making

Composers, conductors and players: Harmony and discord in South African foreign policy making TIM HUGHES KONRAD-ADENAUER-STIFTUNG • OCCASIONAL PAPERS • JOHANNESBURG • SEPTEMBER 2004 © KAS, 2004 All rights reserved While copyright in this publication as a whole is vested in the Konrad-Adenauer- Stiftung, copyright in the text rests with the individual authors, and no paper may be reproduced in whole or part without the express permission, in writing, of both authors and the publisher. It should be noted that any opinions expressed are the responsibility of the individual authors and that the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung does not necessarily subscribe to the opinions of contributors. ISBN: 0-620-33027-9 Published by: Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung 60 Hume Road Dunkeld 2196 Johannesburg Republic of South Africa PO Box 1383 Houghton 2041 Johannesburg Republic of South Africa Telephone: (+27 +11) 214-2900 Telefax: (+27 +11) 214-2913/4 E-mail: [email protected] www.kas.org.za Editing, DTP and production: Tyrus Text and Design Cover design: Heather Botha Reproduction: Rapid Repro Printing: Stups Printing Foreword The process of foreign policy making in South Africa during its decade of democracy has been subject to a complex interplay of competing forces. Policy shifts of the post-apartheid period not only necessitated new visions for the future but also new structures. The creation of a value-based new identity in foreign policy needed to be accompanied by a transformation of institutions relevant for the decision-making process in foreign policy. Looking at foreign policy in the era of President Mbeki, however, it becomes obvious that Max Weber’s observation that “in a modern state the actual ruler is necessarily and unavoidably the bureaucracy, since power is exercised neither through parliamentary speeches nor monarchical enumerations but through the routines of administration”,* no longer holds in the South African context. -

Re: Women Elected to South African Government

Re: Women Elected to South African Government http://www.aluka.org/action/showMetadata?doi=10.5555/AL.SFF.DOCUMENT.af000400 Use of the Aluka digital library is subject to Aluka’s Terms and Conditions, available at http://www.aluka.org/page/about/termsConditions.jsp. By using Aluka, you agree that you have read and will abide by the Terms and Conditions. Among other things, the Terms and Conditions provide that the content in the Aluka digital library is only for personal, non-commercial use by authorized users of Aluka in connection with research, scholarship, and education. The content in the Aluka digital library is subject to copyright, with the exception of certain governmental works and very old materials that may be in the public domain under applicable law. Permission must be sought from Aluka and/or the applicable copyright holder in connection with any duplication or distribution of these materials where required by applicable law. Aluka is a not-for-profit initiative dedicated to creating and preserving a digital archive of materials about and from the developing world. For more information about Aluka, please see http://www.aluka.org Re: Women Elected to South African Government Alternative title Re: Women Elected to South African Government Author/Creator Kagan, Rachel; Africa Fund Publisher Africa Fund Date 1994-06-01 Resource type Reports Language English Subject Coverage (spatial) South Africa Coverage (temporal) 1994 Source Africa Action Archive Rights By kind permission of Africa Action, incorporating the American Committee on Africa, The Africa Fund, and the Africa Policy Information Center. Description Women. Constituent Assembly.