Writing Necklacing Into a History of Liberation Struggle in South Africa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

South Africaâ•Žs Post-Apartheid Foreign Policy Towards Africa

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Iowa Research Online Electronic Journal of Africana Bibliography Volume 6 South Africa’s Post-Apartheid Foreign Policy Article 1 Towards Africa 2-6-2001 South Africa’s Post-Apartheid Foreign Policy Towards Africa Roger Pfister Swiss Federal Institute of Technology ETH, Zurich Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.uiowa.edu/ejab Part of the African History Commons, and the African Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation Pfister, Roger (2001) "South Africa’s Post-Apartheid Foreign Policy Towards Africa," Electronic Journal of Africana Bibliography: Vol. 6 , Article 1. https://doi.org/10.17077/1092-9576.1003 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Iowa Research Online. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Journal of Africana Bibliography by an authorized administrator of Iowa Research Online. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Volume 6 (2000) South Africa’s Post-Apartheid Foreign Policy Towards Africa Roger Pfister, Centre for International Studies, Swiss Federal Institute of Technology ETH, Zurich Preface 1. Introduction Two principal factors have shaped South Africa’s post-apartheid foreign policy towards Africa. First, the termination of apartheid in 1994 allowed South Africa, for the first time in the country’s history, to establish and maintain contacts with African states on equal terms. Second, the end of the Cold War at the end of the 1980s led to a retreat of the West from Africa, particularly in the economic sphere. Consequently, closer cooperation among all African states has become more pertinent to finding African solutions to African problems. -

Of Trials, Reparation, and Transformation in Post-Apartheid South Africa: the Making of a Common Purpose

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE NYLS Law Review Vols. 22-63 (1976-2019) Volume 60 Issue 2 Twenty Years of South African Constitutionalism: Constitutional Rights, Article 6 Judicial Independence and the Transition to Democracy January 2016 Of Trials, Reparation, and Transformation in Post-Apartheid South Africa: The Making of A Common Purpose ANDREA DURBACH Professor of Law and Director of the Australian Human Rights Centre, Faculty of Law, University of New South Wales, Australia Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.nyls.edu/nyls_law_review Part of the Constitutional Law Commons Recommended Citation ANDREA DURBACH, Of Trials, Reparation, and Transformation in Post-Apartheid South Africa: The Making of A Common Purpose, 60 N.Y.L. SCH. L. REV. (2015-2016). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@NYLS. It has been accepted for inclusion in NYLS Law Review by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@NYLS. NEW YORK LAW SCHOOL LAW REVIEW VOLUME 60 | 2015/16 VOLUME 60 | 2015/16 Andrea Durbach Of Trials, Reparation, and Transformation in Post-Apartheid South Africa: The Making of A Common Purpose 60 N.Y.L. Sch. L. Rev. 409 (2015–2016) ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Andrea Durbach is a Professor of Law and Director of the Australian Human Rights Centre, Faculty of Law, University of New South Wales, Australia. Born and educated in South Africa, she practiced as a political trial lawyer, representing victims and opponents of apartheid laws. In 1988 she was appointed solicitor to twenty-five black defendants in a notorious death penalty case in South Africa and later published an account of her experiences in Andrea Durbach, Upington: A Story of Trials and Reconciliation (1999) (for information on the other editions of this book see infra note 42), on which the documentary, A Common Purpose (Looking Glass Pictures 2011) is based. -

Crowd Psychology in South African Murder Trials

Crowd Psychology in South African Murder Trials Andrew M. Colman University of Leicester, Leicester, England South African courts have recently accepted social psy guided by the evidence before him and by his knowledge of the chological phenomena as extenuating factors in murder case as to whether there were extenuating circumstances or not. trials. In one important case, eight railway workers were (cited in Davis, 1989, pp. 205-206) convicted ofmurdering four strike breakers during an in The South African legislature did not define extenuating dustrial dispute. The court accepted coriformity, obedience, circumstances, nor did it place any limit on the factors group polarization, deindividuation, bystander apathy, that might be deemed to be extenuating. In principle, and other well-established psychological phenomena as anything that tended to reduce the moral blameworthi extenuating factors for four of the eight defendants, but ness of a murderer's actions might count as an extenuating sentenced the others to death. In a second trial, death circumstance. In practice, the courts most often accepted sentences o/five defendants for the "necklace" killing of as extenuating such factors as provocation, intoxication, a young woman were reduced to 20 months imprisonment youth, absence of premeditation, and duress (short of in the light ofsimilar social psychological evidence. Prac irresistible compulsion, which would exonerate the de tical and ethical issues arising from expert psychological fendant entirely). The question of extenuation -

The Burundi Peace Process

ISS MONOGRAPH 171 ISS Head Offi ce Block D, Brooklyn Court 361 Veale Street New Muckleneuk, Pretoria, South Africa Tel: +27 12 346-9500 Fax: +27 12 346-9570 E-mail: [email protected] Th e Burundi ISS Addis Ababa Offi ce 1st Floor, Ki-Ab Building Alexander Pushkin Street PEACE CONDITIONAL TO CIVIL WAR FROM PROCESS: THE BURUNDI PEACE Peace Process Pushkin Square, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia Th is monograph focuses on the role peacekeeping Tel: +251 11 372-1154/5/6 Fax: +251 11 372-5954 missions played in the Burundi peace process and E-mail: [email protected] From civil war to conditional peace in ensuring that agreements signed by parties to ISS Cape Town Offi ce the confl ict were adhered to and implemented. 2nd Floor, Armoury Building, Buchanan Square An AU peace mission followed by a UN 160 Sir Lowry Road, Woodstock, South Africa Tel: +27 21 461-7211 Fax: +27 21 461-7213 mission replaced the initial SA Protection Force. E-mail: [email protected] Because of the non-completion of the peace ISS Nairobi Offi ce process and the return of the PALIPEHUTU- Braeside Gardens, Off Muthangari Road FNL to Burundi, the UN Security Council Lavington, Nairobi, Kenya Tel: +254 20 386-1625 Fax: +254 20 386-1639 approved the redeployment of an AU mission to E-mail: [email protected] oversee the completion of the demobilisation of ISS Pretoria Offi ce these rebel forces by December 2008. Block C, Brooklyn Court C On 18 April 2009, at a ceremony to mark the 361 Veale Street ON beginning of the demobilisation of thousands New Muckleneuk, Pretoria, South Africa DI Tel: +27 12 346-9500 Fax: +27 12 460-0998 TI of PALIPEHUTU-FNL combatants, Agathon E-mail: [email protected] ON Rwasa, leader of PALIPEHUTU-FNL, gave up AL www.issafrica.org P his AK-47 and military uniform. -

No. 532, August 2, 1991

25¢ WfJRIlERI ".'(J'R'~X-523 No. 532 2 August 1991 30 Million Blacks Still Can't Vote, Endure Abject Poverty South Africa: ANe Pushes "Post-Apartheid" Swindle Gamma Photos While Nelson Mandela and South African president De Klerk shake on "deal," blacks are still victims of apartheid terror. Government Unleashes Inkatha Killers "The new South Africa .is on the up segregated living areas, and the Land looked to the imperialists to clean up regime of white supremacy remains and march," crowed President EW. De Klerk Act, guaranteeing white ownership of the South African racist regime, George the hopes of the impoverished black after the segregated parliament voted in 87 percent of the land, are now officially Bush issued an executive order lifting majority are being dashed. In the "new June to repeal the remaining key pillars abolished. Thereupon, the European U.S. sanctions on trade,' irrvestment and South Africa," thousands are slaugh of "grand apartheid." The Population Common Market voted to lift sanctions, banking. tered by government-instigated terror, Registration Act, which classified every and the 21-year ban on South African Now the formal statutes of apartheid millions are disenfranchised and con one born in South Africa into four racial participation in Olympic competition have been eliminated (the pass laws and demned to abject poverty. There can categories (white, African, "coloured," was removed. To the chagrin of those Separate Amenities Act were scrapped be no democracy for the toilers who Indian), the Group Areas Act.which set leftists and would-be radicals who earlier), but the cruel oppression of the continued on page 7 Gorbachev Puts Soviet Union .on the Auction Block They called it the "grand bargain." they're demanding that capitalist res It was cooked up by economic advisers toration be in place before Gorbachev of Gorbachev and Yeltsin along with sees any real money. -

Ungovernability and Material Life in Urban South Africa

“WHERE THERE IS FIRE, THERE IS POLITICS”: Ungovernability and Material Life in Urban South Africa KERRY RYAN CHANCE Harvard University Together, hand in hand, with our boxes of matches . we shall liberate this country. —Winnie Mandela, 1986 Faku and I stood surrounded by billowing smoke. In the shack settlement of Slovo Road,1 on the outskirts of the South African port city of Durban, flames flickered between piles of debris, which the day before had been wood-plank and plastic tarpaulin walls. The conflagration began early in the morning. Within hours, before the arrival of fire trucks or ambulances, the two thousand house- holds that comprised the settlement as we knew it had burnt to the ground. On a hillcrest in Slovo, Abahlali baseMjondolo (an isiZulu phrase meaning “residents of the shacks”) was gathered in a mass meeting. Slovo was a founding settlement of Abahlali, a leading poor people’s movement that emerged from a burning road blockade during protests in 2005. In part, the meeting was to mourn. Five people had been found dead that day in the remains, including Faku’s neighbor. “Where there is fire, there is politics,” Faku said to me. This fire, like others before, had been covered by the local press and radio, some journalists having been notified by Abahlali via text message and online press release. The Red Cross soon set up a makeshift soup kitchen, and the city government provided emergency shelter in the form of a large, brightly striped communal tent. Residents, meanwhile, CULTURAL ANTHROPOLOGY, Vol. 30, Issue 3, pp. 394–423, ISSN 0886-7356, online ISSN 1548-1360. -

The Foreign Policies of Mandela and Mbeki: a Clear Case of Idealism Vs Realism ?

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Stellenbosch University SUNScholar Repository THE FOREIGN POLICIES OF MANDELA AND MBEKI: A CLEAR CASE OF IDEALISM VS REALISM ? by CHRISTIAN YOULA Thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts (International Studies) at Stellenbosch University Department of Political Science Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences Supervisor: Dr Karen Smith March 2009 Declaration By submitting this thesis electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own, original work, that I am the owner of the copyright thereof and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. Date: 28 February 2009 Copyright © 2009 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved i Abstract After 1994, South African foreign policymakers faced the challenge of reintegrating a country, isolated for many years as a result of the previous government’s apartheid policies, into the international system. In the process of transforming South Africa's foreign identity from a pariah state to a respected international player, some commentators contend that presidents Mandela and Mbeki were informed by two contrasting theories of International Relations (IR), namely, idealism and realism, respectively. In light of the above-stated popular assumptions and interpretations of the foreign policies of Presidents Mandela and Mbeki, this study is motivated by the primary aim to investigate the classification of their foreign policy within the broader framework of IR theory. This is done by sketching a brief overview of the IR theories of idealism, realism and constructivism, followed by an analysis of the foreign policies of these two statesmen in order to identify some of the principles that underpin them. -

South Africa Tackles Global Apartheid: Is the Reform Strategy Working? - South Atlantic Quarterly, 103, 4, 2004, Pp.819-841

critical essays on South African sub-imperialism regional dominance and global deputy-sheriff duty in the run-up to the March 2013 BRICS summit by Patrick Bond Neoliberalism in SubSaharan Africa: From structural adjustment to the New Partnership for Africas Development – in Alfredo Saad-Filho and Deborah Johnstone (Eds), Neoliberalism: A Critical Reader, London, Pluto Press, 2005, pp.230-236. US empire and South African subimperialism - in Leo Panitch and Colin Leys (Eds), Socialist Register 2005: The Empire Reloaded, London, Merlin Press, 2004, pp.125- 144. Talk left, walk right: Rhetoric and reality in the New South Africa – Global Dialogue, 2004, 6, 4, pp.127-140. Bankrupt Africa: Imperialism, subimperialism and financial politics - Historical Materialism, 12, 4, 2004, pp.145-172. The ANCs “left turn” and South African subimperialism: Ideology, geopolitics and capital accumulation - Review of African Political Economy, 102, September 2004, pp.595-611. South Africa tackles Global Apartheid: Is the reform strategy working? - South Atlantic Quarterly, 103, 4, 2004, pp.819-841. Removing Neocolonialisms APRM Mask: A critique of the African Peer Review Mechanism – Review of African Political Economy, 36, 122, December 2009, pp. 595-603. South African imperial supremacy - Le Monde Diplomatique, Paris, May 2010. South Africas dangerously unsafe financial intercourse - Counterpunch, 24 April 2012. Financialization, corporate power and South African subimperialism - in Ronald W. Cox, ed., Corporate Power in American Foreign Policy, London, Routledge Press, 2012, pp.114-132. Which Africans will Obama whack next? – forthcoming in Monthly Review, January 2012. 2 Neoliberalism in SubSaharan Africa: From structural adjustment to the New Partnership for Africa’s Development Introduction Distorted forms of capital accumulation and class formation associated with neoliberalism continue to amplify Africa’s crisis of combined and uneven development. -

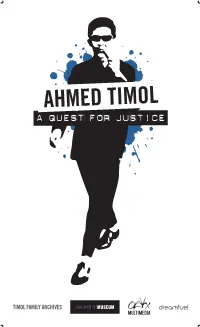

Ahmed Timol Was the First Detainee to Die at John Vorster Square

“He hung from a piece of soap while washing…” In Detention, Chris van Wyk, 1979 On 23 August 1968, Prime Minister Vorster opened a new police station in Johannesburg known as John Vorster Square. Police described it as a state of the art facility, where incidents such as the 1964 “suicide” of political detainee, Suliman “Babla” Saloojee, could be avoided. On 9 September 1964 Saloojee fell or was thrown from the 7th floor of the old Gray’s Building, the Special Branch’s then-headquarters in Johannesburg. Security police routinely tortured political detainees on the 9th and 10th floors of John Vorster Square. Between 1971 and 1990 a number of political detainees died there. Ahmed Timol was the first detainee to die at John Vorster Square. 27 October 1971 – Ahmed Timol 11 December 1976 – Mlungisi Tshazibane 15 February 1977 – Matthews Marwale Mabelane 5 February 1982 – Neil Aggett 8 August 1982 – Ernest Moabi Dipale 30 January 1990 – Clayton Sizwe Sithole 1 Rapport, 31 October 1971 Courtesy of the Timol Family Courtesy of the Timol A FAMILY ON THE MOVE Haji Yusuf Ahmed Timol, Ahmed Timol’s father, was The young Ahmed suffered from bronchitis and born in Kholvad, India, and travelled to South Africa in became a patient of Dr Yusuf Dadoo, who was the 1918. In 1933 he married Hawa Ismail Dindar. chairman of the South African Indian Congress and the South African Communist Party. Ahmed Timol, one of six children, was born in Breyten in the then Transvaal, on 3 November 1941. He and his Dr Dadoo’s broad-mindedness and pursuit of siblings were initially home-schooled because there was non-racialism were to have a major influence on no school for Indian children in Breyten. -

Harmony and Discord in South African Foreign Policy Making

Composers, conductors and players: Harmony and discord in South African foreign policy making TIM HUGHES KONRAD-ADENAUER-STIFTUNG • OCCASIONAL PAPERS • JOHANNESBURG • SEPTEMBER 2004 © KAS, 2004 All rights reserved While copyright in this publication as a whole is vested in the Konrad-Adenauer- Stiftung, copyright in the text rests with the individual authors, and no paper may be reproduced in whole or part without the express permission, in writing, of both authors and the publisher. It should be noted that any opinions expressed are the responsibility of the individual authors and that the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung does not necessarily subscribe to the opinions of contributors. ISBN: 0-620-33027-9 Published by: Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung 60 Hume Road Dunkeld 2196 Johannesburg Republic of South Africa PO Box 1383 Houghton 2041 Johannesburg Republic of South Africa Telephone: (+27 +11) 214-2900 Telefax: (+27 +11) 214-2913/4 E-mail: [email protected] www.kas.org.za Editing, DTP and production: Tyrus Text and Design Cover design: Heather Botha Reproduction: Rapid Repro Printing: Stups Printing Foreword The process of foreign policy making in South Africa during its decade of democracy has been subject to a complex interplay of competing forces. Policy shifts of the post-apartheid period not only necessitated new visions for the future but also new structures. The creation of a value-based new identity in foreign policy needed to be accompanied by a transformation of institutions relevant for the decision-making process in foreign policy. Looking at foreign policy in the era of President Mbeki, however, it becomes obvious that Max Weber’s observation that “in a modern state the actual ruler is necessarily and unavoidably the bureaucracy, since power is exercised neither through parliamentary speeches nor monarchical enumerations but through the routines of administration”,* no longer holds in the South African context. -

South Africa's Relations with Iraq

South African Journal of International Affairs, 2014 Vol. 00, No. 00, 1–19, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10220461.2014.940374 Playing in the orchestra of peace: South Africa’s relations with Iraq (1998–2003) Jo-Ansie van Wyk* University of South Africa, Pretoria, South Africa South Africa’s status and prestige as a country that successfully and unilaterally disarmed its weapons of mass destruction (WMD) programme enabled it to engage with the Saddam government of Iraq in the months leading up to the US-led invasion of March 2003. Following intense international diplomatic efforts, Saddam Hussein had agreed to allow UN and International Atomic Energy Agency weapons inspectors to enter Iraq in November 2002. Acting outside the UN Security Council, the US and its coalition partners maintained that Iraq continued to maintain and produce WMD, a claim refuted by weapons inspectors, including a South African disarmament team that visited Iraq in February 2003. Employing three diplomatic strategies associated with niche diplomacy, South Africa contributed to attempts to avert the invasion by assisting with the orderly disarmament of Saddam-led Iraq and by practising multilateralism. These strategies, notwithstanding the US-led invasion signalling a failure of South Africa’s niche diplomacy in this instance, provide valuable insight into the nuclear diplomacy of South Africa. Keywords: South Africa; Iraq; Saddam Hussein; Thabo Mbeki; weapons of mass destruction; niche diplomacy; nuclear diplomacy Introduction On 20 March 2003, the US led a military invasion along with the UK, Australia and Poland into Iraq. The invasion followed, inter alia, US Secretary of State Colin Powell’s presentation to the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) on 5 February 2003 claiming that the US had found new evidence that Iraq had been developing weapons of mass destruction (WMD). -

Shakespeare in South Africa: an Examination of Two Performances of Titus Andronicus in Apartheid and Post- Apartheid South Africa

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 8-2017 Shakespeare in South Africa: An Examination of Two Performances of Titus Andronicus in Apartheid and Post- Apartheid South Africa Erin Elizabeth Whitaker University of Tennessee, Knoxville, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the Other English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Whitaker, Erin Elizabeth, "Shakespeare in South Africa: An Examination of Two Performances of Titus Andronicus in Apartheid and Post-Apartheid South Africa. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2017. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/4911 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Erin Elizabeth Whitaker entitled "Shakespeare in South Africa: An Examination of Two Performances of Titus Andronicus in Apartheid and Post- Apartheid South Africa." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Master of Arts, with a major in English. Heather A. Hirschfeld, Major Professor We have read