Nelson Mandela: Partisan and Peacemaker

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Deadlands: Reloaded Core Rulebook

This electronic book is copyright Pinnacle Entertainment Group. Redistribution by print or by file is strictly prohibited. This pdf may be printed for personal use. The Weird West Reloaded Shane Lacy Hensley and BD Flory Savage Worlds by Shane Lacy Hensley Credits & Acknowledgements Additional Material: Simon Lucas, Paul “Wiggy” Wade-Williams, Dave Blewer, Piotr Korys Editing: Simon Lucas, Dave Blewer, Piotr Korys, Jens Rushing Cover, Layout, and Graphic Design: Aaron Acevedo, Travis Anderson, Thomas Denmark Typesetting: Simon Lucas Cartography: John Worsley Special Thanks: To Clint Black, Dave Blewer, Kirsty Crabb, Rob “Tex” Elliott, Sean Fish, John Goff, John & Christy Hopler, Aaron Isaac, Jay, Amy, and Hayden Kyle, Piotr Korys, Rob Lusk, Randy Mosiondz, Cindi Rice, Dirk Ringersma, John Frank Rosenblum, Dave Ross, Jens Rushing, Zeke Sparkes, Teller, Paul “Wiggy” Wade-Williams, Frank Uchmanowicz, and all those who helped us make the original Deadlands a premiere property. Fan Dedication: To Nick Zachariasen, Eric Avedissian, Sean Fish, and all the other Deadlands fans who have kept us honest for the last 10 years. Personal Dedication: To mom, dad, Michelle, Caden, and Ronan. Thank you for all the love and support. You are my world. B.D.’s Dedication: To my parents, for everything. Sorry this took so long. Interior Artwork: Aaron Acevedo, Travis Anderson, Chris Appel, Tom Baxa, Melissa A. Benson, Theodor Black, Peter Bradley, Brom, Heather Burton, Paul Carrick, Jim Crabtree, Thomas Denmark, Cris Dornaus, Jason Engle, Edward Fetterman, -

Nelson-Mandelas-Legacy.Pdf

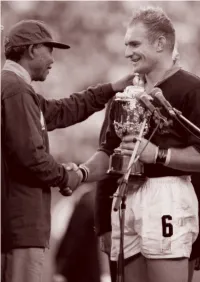

Nelson Mandela’s Legacy What the World Must Learn from One of Our Greatest Leaders By John Carlin ver since Nelson Mandela became president of South Africa after winning his Ecountry’s fi rst democratic elections in April 1994, the national anthem has consisted of two songs spliced—not particularly mellifl uously—together. One is “Nkosi Sikelel’ iAfrika,” or “God Bless Africa,” sung at black protest ral- lies during the forty-six years between the rise and fall of apartheid. The other is “Die Stem,” (“The Call”), the old white anthem, a celebration of the European settlers’ conquest of Africa’s southern tip. It was Mandela’s idea to juxtapose the two, his purpose being to forge from the rival tunes’ discordant notes a powerfully symbolic message of national harmony. Not everyone in Mandela’s party, the African National Congress, was con- vinced when he fi rst proposed the plan. In fact, the entirety of the ANC’s national executive committee initially pushed to scrap “Die Stem” and replace it with “Nkosi Sikelel’ iAfrika.” Mandela won the argument by doing what defi ned his leadership: reconciling generosity with pragmatism, fi nding common ground between humanity’s higher values and the politician’s aspiration to power. The chief task the ANC would have upon taking over government, Mandela reminded his colleagues at the meeting, would be to cement the foundations of the hard-won new democracy. The main threat to peace and stability came from right-wing terrorism. The way to deprive the extremists of popular sup- port, and therefore to disarm them, was by convincing the white population as a whole President Nelson Mandela and that they belonged fully in the ‘new South Francois Pienaar, captain of the Africa,’ that a black-led government would South African Springbok rugby not treat them the way previous white rulers team, after the Rugby World Cup had treated blacks. -

PRENEGOTIATION Ln SOUTH AFRICA (1985 -1993) a PHASEOLOGICAL ANALYSIS of the TRANSITIONAL NEGOTIATIONS

PRENEGOTIATION lN SOUTH AFRICA (1985 -1993) A PHASEOLOGICAL ANALYSIS OF THE TRANSITIONAL NEGOTIATIONS BOTHA W. KRUGER Thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts at the University of Stellenbosch. Supervisor: ProfPierre du Toit March 1998 Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za DECLARATION I, the undersigned, hereby declare that the work contained in this thesis is my own original work and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it at any university for a degree. Signature: Date: The fmancial assistance of the Centre for Science Development (HSRC, South Africa) towards this research is hereby acknowledged. Opinions expressed and conclusions arrived at, are those of the author and are not necessarily to be attributed to the Centre for Science Development. Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za OPSOMMING Die opvatting bestaan dat die Suid-Afrikaanse oorgangsonderhandelinge geinisieer is deur gebeurtenisse tydens 1990. Hierdie stuC.:ie betwis so 'n opvatting en argumenteer dat 'n noodsaaklike tydperk van informele onderhandeling voor formele kontak bestaan het. Gedurende die voorafgaande tydperk, wat bekend staan as vooronderhandeling, het lede van die Nasionale Party regering en die African National Congress (ANC) gepoog om kommunikasiekanale daar te stel en sodoende die moontlikheid van 'n onderhandelde skikking te ondersoek. Deur van 'n fase-benadering tot onderhandeling gebruik te maak, analiseer hierdie studie die oorgangstydperk met die doel om die struktuur en funksies van Suid-Afrikaanse vooronderhandelinge te bepaal. Die volgende drie onderhandelingsfases word onderskei: onderhande/ing oor onderhandeling, voorlopige onderhande/ing, en substantiewe onderhandeling. Beide fases een en twee word beskou as deel van vooronderhandeling. -

Gender and the Truth and Reconciliation Commission

Gender and the Truth and Reconciliation Commission A submission to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission Prepared by Beth Goldblatt and Shiela Meintjes May 1996 Dr Shiela Meintjes Beth Goldblatt Department of Political Studies Gender Research Project University of the Witwatersrand Centre for Applied Legal Studies Private Bag 3 University of the Witwatersrand Wits Private Bag 3 2050 Wits Tel: 011-716-3339 2050 Fax: 011-403-7482 Tel: 011-403-6918 Fax: 011-403-2341 CONTENTS A. INTRODUCTION B. WHY GENDER? C. AN HISTORICAL ANALYSIS OF WOMEN'S EXPERIENCE OF REPRESSION, RESISTANCE AND TORTURE o THE 1960s o THE 1970s o THE 1980s D. HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS - A GENDER PERSPECTIVE I. UNDERSTANDING GENDER AND POLITICAL VIOLENCE 1. WOMEN AS DIRECT AND INDIRECT VICTIMS OF APARTHEID 2. CONSTRUCTIONS OF GENDER IN PRISON: THE WAYS IN WHICH WOMEN EXPERIENCED TORTURE 3. THE IMPACT OF RACE AND CLASS ON WOMEN'S EXPERIENCE OF POLITICAL VIOLENCE 4. WOMEN AS PERPETRATORS II. SITES OF POLITICAL VIOLENCE 1. GENDER AND TOWNSHIP VIOLENCE 2. VIOLENCE IN KWA-ZULU/NATAL 3. HOSTEL/THIRD FORCE VIOLENCE 4. VIOLENCE AGAINST WOMEN IN NEIGHBOURING STATES 5. GENDERED VIOLENCE IN THE LIBERATION MOVEMENTS E. AMNESTY AND GENDER F. REPARATIONS AND GENDER G. PROPOSED MECHANISMS TO ACCOMMODATE GENDER IN THE TRC PROCESS H. CONCLUSION I. APPENDIX: INTERVIEW INFORMANTS J. BIBLIOGRAPHY A. INTRODUCTION The Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) will play an extremely significant role in shaping South Africa's collective understanding of our painful past. It will also have to deal with the individual victims, survivors and perpetrators who come before it and will have to consider important matters relating to reparation and rehabilitation. -

A Case Study of the Charges Against Jacob Zuma

• THE MEDIA AND SOCIAL CONSTRUCTION OF REALITY: A CASE STUDY OF THE CHARGES AGAINST JACOB ZUMA By Lungisile Zamahlongwa Khuluse Submitted in Partial Fulfilment for the Requirements of the Master of Arts: Social Policy, University of Kwazulu Natal: Durban. February 2011 DECLARATION Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of MA S_o(:ialPolic;:y, in the Graduate Programme in SQ_ (:iaLPQli~y, University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. I declare that this dissertation is my own unaided work. All citations, references and borrowed ideas have been duly acknowledged. I confirm that an external editor was not used. This dissertation is being submitted for the degree of MA_S_odaLpQIic;:y in the Faculty of Humanities, Development and Social Science, University of KwaZulu Natal, South Africa. None of the present work has been submitted previously for any degree or examination in any other University. Lungisile Zamahlongwa Khuluse Student name 29 February 2011 Date prof. p. M. Zulu Supervisor ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Firstly I would like to thank the Lord Almighty for giving me strength and resources to complete this dissertation. I am indebted to my parents, Jabulisile Divi Khuluse and Sazi Abednigo Khuluse for their support, love, patience and understanding; I thank them for inspiring me to be the best I can possibly be and for being my pillar of strength. I am grateful to my siblings Lihle, Sfiso and Mpume 'Pho' for all their support. I thank my grandmother Mrs. K. J. Luthuli. Gratitude is also due to my friends Nontobeko Nzama, Sindisiwe Nzama, Nenekazi Jukuda, Zonke Khumalo, Jabulile Thusi, and Hlalo Thusi, for being there for me. -

The Rollback of South Africa's Chemical and Biological Warfare

The Rollback of South Africa’s Chemical and Biological Warfare Program Stephen Burgess and Helen Purkitt US Air Force Counterproliferation Center Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama THE ROLLBACK OF SOUTH AFRICA’S CHEMICAL AND BIOLOGICAL WARFARE PROGRAM by Dr. Stephen F. Burgess and Dr. Helen E. Purkitt USAF Counterproliferation Center Air War College Air University Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama The Rollback of South Africa’s Chemical and Biological Warfare Program Dr. Stephen F. Burgess and Dr. Helen E. Purkitt April 2001 USAF Counterproliferation Center Air War College Air University Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama 36112-6427 The internet address for the USAF Counterproliferation Center is: http://www.au.af.mil/au/awc/awcgate/awc-cps.htm . Contents Page Disclaimer.....................................................................................................i The Authors ............................................................................................... iii Acknowledgments .......................................................................................v Chronology ................................................................................................vii I. Introduction .............................................................................................1 II. The Origins of the Chemical and Biological Warfare Program.............3 III. Project Coast, 1981-1993....................................................................17 IV. Rollback of Project Coast, 1988-1994................................................39 -

Growing up with Vertigo: British Writers, Dc, and the Maturation of American Comic Books

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by ScholarWorks @ UVM GROWING UP WITH VERTIGO: BRITISH WRITERS, DC, AND THE MATURATION OF AMERICAN COMIC BOOKS A Thesis Presented by Derek A. Salisbury to The Faculty of the Graduate College of The University of Vermont In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts Specializing in History May, 2013 Accepted by the Faculty of the Graduate College, The University of Vermont, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts, specializing in History. Thesis Examination Committee: ______________________________________ Advisor Abigail McGowan, Ph.D ______________________________________ Melanie Gustafson, Ph.D ______________________________________ Chairperson Elizabeth Fenton, Ph.D ______________________________________ Dean, Graduate College Domenico Grasso, Ph.D March 22, 2013 Abstract At just under thirty years the serious academic study of American comic books is relatively young. Over the course of three decades most historians familiar with the medium have recognized that American comics, since becoming a mass-cultural product in 1939, have matured beyond their humble beginnings as a monthly publication for children. However, historians are not yet in agreement as to when the medium became mature. This thesis proposes that the medium’s maturity was cemented between 1985 and 2000, a much later point in time than existing texts postulate. The project involves the analysis of how an American mass medium, in this case the comic book, matured in the last two decades of the twentieth century. The goal is to show the interconnected relationships and factors that facilitated the maturation of the American sequential art, specifically a focus on a group of British writers working at DC Comics and Vertigo, an alternative imprint under the financial control of DC. -

South African Foreign Policy and Human Rights: South Africa’S Foreign Policy on Israel (2008-2014) in Relation to the Palestinian Question

SOUTH AFRICAN FOREIGN POLICY AND HUMAN RIGHTS: SOUTH AFRICA’S FOREIGN POLICY ON ISRAEL (2008-2014) IN RELATION TO THE PALESTINIAN QUESTION MPhil Mini-dissertation By QURAYSHA ISMAIL SOOLIMAN Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree (MPhil) Multi-disciplinary human rights Prepared under the supervision of Professor Anton du Plessis At the Faculty of Law, University of Pretoria 06 August 2014 0 © University of Pretoria DECLARATION I, Quraysha Ismail Sooliman, hereby declare that this mini-dissertation is original and has never been presented in the University of Pretoria or any other institution. I also declare that any secondary information used has been duly acknowledged in this mini-dissertation. Student: Quraysha Ismail Sooliman Signature: --------------------------------- Date: --------------------------------- Supervisor: Professor Anton du Plessis Signature: --------------------------------- Date: ---------------------------------- 1 © University of Pretoria DEDICATION To all the martyrs of Gaza, specifically, the ‘Eid’ martyrs (28 July 2014). 2 © University of Pretoria ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS All praises are to God who gave me the ability and the opportunity to do this study. When I decided to pursue this programme, I was at first overwhelmed and unsure of my ability to complete this task. I therefore would like to begin by thanking my Head of Department, Professor Maxi Schoeman who believed in me and my ability to do this programme and the Centre of Human Rights, University of Pretoria for giving me this opportunity. The scope and extent of this course has been invigorating, inspirational, unique and truly transformative to my understanding on many issues. My sincerest gratitude and appreciation goes to my supervisor Professor Anton du Plessis for his professional, sincere and committed assistance in ensuring that this work has been completed timeously. -

Report of the 54Th National Conference Report of the 54Th National Conference

REPORT OF THE 54TH NATIONAL CONFERENCE REPORT OF THE 54TH NATIONAL CONFERENCE CONTENTS 1. Introduction by the Secretary General 1 2. Credentials Report 2 3. National Executive Committee 9 a. Officials b. NEC 4. Declaration of the 54th National Conference 11 5. Resolutions a. Organisational Renewal 13 b. Communications and the Battle of Ideas 23 c. Economic Transformation 30 d. Education, Health and Science & Technology 35 e. Legislature and Governance 42 f. International Relations 53 g. Social Transformation 63 h. Peace and Stability 70 i. Finance and Fundraising 77 6. Closing Address by the President 80 REPORT OF THE 54TH NATIONAL CONFERENCE 1 INTRODUCTION BY THE SECRETARY GENERAL COMRADE ACE MAGASHULE The 54th National Conference was convened under improves economic growth and meaningfully addresses the theme of “Remember Tambo: Towards inequality and unemployment. Unity, Renewal and Radical Socio-economic Transformation” and presented cadres of Conference reaffirmed the ANC’s commitment to our movement with a concrete opportunity for nation-building and directed all ANC structures to introspection, self-criticism and renewal. develop specific programmmes to build non-racialism and non-sexism. It further directed that every ANC The ANC can unequivocally and proudly say that we cadre must become activists in their communities and emerged from this conference invigorated and renewed drive programmes against the abuse of drugs and to continue serving the people of South Africa. alcohol, gender based violence and other social ills. Fundamentally, Conference directed every ANC We took fundamental resolutions aimed at radically member to work tirelessly for the renewal of our transforming the lives of the people for the better and organisation and to build unity across all structures. -

Petitioner's Brief, Ben and Diane Goldstein V

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF APPEALS OF WEST VIRGI~1A BEN GOLDSTEIN and DIANE GOLDSTEIN, ~ra-n~"'EC-;~;-2"'2D"-!!!'~!!!!'I~-v- husband and wife, Plaintiffs Below/Petitioners, CASE NO. 17-0796 v. (Berkeley Co. Civil Action No. 15-C-520) PEACEMAKER PROPERTIES, LLC, a West Virginia Limited Liability Company, and PEACEMAKER NATIONAL TRAINING CENTER, LLC, a West Virginia Limited Liability Company, Defendants Below/Respondents. PETITIONERS' BRIEF Appeal Arising from Orders Entered on August 9, 2017 and August 11,2017 in Civil Action No. 15-C-520 in the Circuit Court ofBerkeley County, West Virginia Joseph L. Caltrider WVSB#6870 BOWLES RICE LLP Post Office Drawer 1419 Martinsburg, West Virginia 25402-1419 (304) 264-4214 [email protected] Counselfor the Petitioners TABLE OF CONTENTS ASSIGNMENTS OF ERROR .........................................................................................................1 STATEl\1ENT OF THE CASE ........................................................................................................ 1 I. STATEMENT OF FACTS ...................................................................................... 1 II. DISCOVERY DISPUTE .........................................................................................9 III. REMAINING PROCEDURAL HISTORy........................................................... 14 SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT .....................................................................................................23 STATEl\1ENT REGARDING ORAL ARGUMENT AND DECISION ......................................27 -

The Rise of the South African Security Establishment an Essay on the Changing Locus of State Power

BRADLOW SERIE£ r NUMBER ONE - ft \\ \ "*\\ The Rise of the South African Security Establishment An Essay on the Changing Locus of State Power Kenneth W. Grundy THl U- -" , ., • -* -, THE SOUTH AFRICAN INSTITUTE OF INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS The Rise of the South African Security Establishment An Essay on the Changing Locus of State Power Kenneth W, Grundy THE SOUTH AFRICAN INSTITUTE OF INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS August 1983 BRADLOW PAPER NO. 1 THE BRADLOW FELLOWSHIP The Bradlow Fellowship is awarded from a grant made to the South African Institute of In- ternational Affairs from the funds of the Estate late H. Bradlow. Kenneth W. Grundy is Professor of Political Science at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, Ohio. Professor Grundy is considered an authority on the role of the military in African affairs. In 1982, Professor Grundy was elected the first Bradlow Fellow at the South African Institute of International Affairs. Founded in Cape Town in 1934, the South African Institute of International Affairs is a fully independent national organisation whose aims are to promote a wider and more informed understanding of international issues — particularly those affecting South Africa — through objective research, study, the dissemination of information and communication between people concerned with these issues, within and outside South Africa. The Institute is privately funded by its corporate and individual members. Although Jan Smuts House is on the Witwatersrand University campus, the Institute is administratively and financially independent. It does not receive government funds from any source. Membership is open to all, irrespective of race, creed or sex, who have a serious interest in international affairs. -

Post-Apartheid Reconciliation and Coexistence in South Africa

Post-Apartheid Reconciliation and Coexistence in South Africa A Comparative Study Visit Report 30th April – 7th May 2013 2 Post-Apartheid Reconciliation and Coexistence in South Africa A Comparative Study Visit Report 30th April – 7th May 2013 May 2013 3 Published by Democratic Progress Institute 11 Guilford Street London WC1N 1DH United Kingdom www.democraticprogress.org [email protected] +44 (0)203 206 9939 First published, 2013 ISBN: 978-1-905592-73-9 © DPI – Democratic Progress Institute, 2013 DPI – Democratic Progress Institute is a charity registered in England and Wales. Registered Charity No. 1037236. Registered Company No. 2922108. This publication is copyright, but may be reproduced by any method without fee or prior permission for teaching purposes, but not for resale. For copying in any other circumstances, prior written permission must be obtained from the publisher, and a fee may be payable.be obtained from the publisher, and a fee may be payable 4 Post-Apartheid Reconciliation and Coexistence in South Africa Contents Foreword ....................................................................................7 Tuesday 30th April –Visit to Robben Island, Table Bay, Cape Town .................................................................................9 Welcome Dinner at Queen Victoria Hotel ............................12 Wednesday 1st May – Visit to Table Mountain ........................17 Lunch at Quay Four Restaurant, Cape Town ........................18 Session 1: Meeting with Fanie Du Toit, Victoria and