Otherness As a European Destiny. Interwar Romanian Views on the European Idea

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HYPERION Revista Apare Sub Egida Uniunii Scriitorilor Din România

YPERION H Revistă de cultură • Anul 38 • Numărul 7-8-9 / 2020 (315-316-317) Revistă de cultură 38 • Numărul • Anul 7-8-9 / 2020 (315-316-317) HYPERION Revista apare sub egida Uniunii Scriitorilor din România CUPRINS Accente George Luca – Vladnic instant și reprimarea inexprimabilului ..............83 Gellu Dorian – Revistele de cultură și pandemia Covid 19 ........................1 Victor Teișanu – Epicul nostalgiilor simbolice în hainele sale de sărbătoare ..................87 Invitatul revistei – Un mare dramaturg și consecvența sa anticomunistă ............................89 Nicolae Oprea ............................................................................................................ 3 – Privind viața prin lentila melancoliei .............................................................92 Nicolae Oprea – Arte poetice suprarealiste în creaţia lui Gellu Naum ...7 Ionel Savitescu Ancheta – Viaţa lui Nae Ionescu ...........................................................................................95 Scriitorul – destin și opțiune: Cristina Ștefan ...............................................11 – Admirabila tăcere .................................................................................................97 – Istoria unirii românilor ........................................................................................99 Dialogurile revistei Nicolae Sava în dialog cu Solomon Marcus ..................................................14 ReLecturi Radu Voinescu – Clasicii, noi și viitorul studiilor umaniste ....................101 -

Format Pdf/Epub

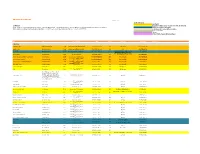

EDITURA HUMANITAS 28 iunie 2019 Cod culoare: NOUTATE CONTACT: Besseller/ Ediție noua/ Cel mai nou titlu în domeniu Ionut Trupina, [email protected], Samuel Magureanu, [email protected], George Brătan, [email protected], Loredana Ediție de colecție/Cartonată Brasoveanu, [email protected]; Ionut Alecu, [email protected]; 021/408 83 53(52) Colecție nouă/ Texte civile.Jurnalism Povestea banilor Albume PRECOMANDĂ www.libhumanitas.ro Titlu Autor Pret Seria/Colecţia ISBN Nr.pag. Observaţii Cod de bare Comanda LITERATURA Fluturele negru Radu Paraschivescu 39.00 Seria de autor Radu Paraschivescu 978-973-50-6397-9 328 Ediție nouă 978-973-50-6397-9 Orașul fetelor Elizabeth Gilbert 49.00 Seria de autor Elizabeth Gilbert 978-973-50-6442-6 412 NOU 9789735064426 Melancolia 49.90 978-973-50-6428-0 256 NOU/BESTSELLER BOOKFEST 2019/ 9789735064280 Mircea Cărtărescu Seria de autor Mircea Cărtărescu EDITIE DE COLECTIE pdf/epub NOU/ BESTSELLER BOOKFEST 2019 Cartea reghinei Ioana Nicolaie 27.00 În afara colecțiilor 978-973-50-6438-9 224 9789735064389 pdf/epub Amintiri din epoca lui Bibi. O post-utopie Andrei Cornea 32.00 Seria de autor Andrei Cornea 978-973-50-6395-5 200 NOU pdf/epub 9789735063825 821.135.1 – scriitori români Trilogia sexului rătăcitor Cristina Vremeș 37.00 978-973-50-6412-9 200 NOU pdf/epub 9789735064129 contemporani 821.135.1 – scriitori români Ziua de naștere a lui Mihai Mihailovici Dumitru Crudu 34.00 978-973-50-6427-3 248 NOU pdf/epub 9789735064273 contemporani 821.135.1 – scriitori români Zilele după -

Număr Special

STUDII ŞI CERCETĂRI DE ISTORIA ARTEI SERIA ARTĂ PLASTICĂ NUMĂR SPECIAL VIITORISMUL AZI O sută de ani de la lansarea Manifestului futurismului Volumul de faţă cuprinde comunicările susţinute la Colocviul „Viitorismul azi. O sută de ani de la lansarea Manifestului futurismului”, care a avut loc la Institutul de Istoria Artei „G. Oprescu” al Academiei Române din Bucureşti, la data de 20 februarie 2009. Coord.: Ioana Vlasiu şi Irina Cărăbaş EDITURA ACADEMIEI ROMÂNE Bucureşti, 2010 STUDII ŞI CERCETĂRI DE ISTORIA ARTEI SERIA ARTĂ PLASTICĂ NUMĂR SPECIAL Cuprins COMUNICĂRI Ioana Vlasiu, „Arta viitorului” în România la începutul secolului XX ........................... 3 Angelo Mitchievici, Decadentism şi avangardism: între barbarie şi utopie................... 15 Gheorghe Vida, Mattis Teutsch şi elaborarea unei semiotici plastice originale ............. 23 Paul Cernat, Futurismul italian şi moştenirea sa culturală în România interbelică: între avangardă şi „tânăra generaţie”.................................................................. 27 Irina Cărăbaş, „Lumea trebuie reinventată”. Câteva note despre pictopoezie şi futurism .................................................................................................................. 33 Cristian-Robert Velescu, Marcel Duchamp şi futurismul ................................................ 47 INVITAŢI Irina Genova, Nicolay Diulgheroff – o identitate artistică multiplă. Consideraţii pe marginea unei expoziţii......................................................................................... -

Un Târgoviºtean Sadea

REVISTÃ LUNARÃ DE CULTURÃ A SOCIETÃÞII SCRIITORILOR TÂRGOVIªTENI Anul XX, Nr. 8-9 (233-234) august-septembrie 2019 Editatã cu sprijinul Consiliului Local Municipal ºi al Primãriei Municipiului Târgoviºte Apare sub egida Uniunii Scriitorilor din România Un târgoviºtean sadea În timp ce unii de diferite ranguri ºi culori politice aºteptau ziua de 10 august râvnind o reiterare amplificatã a rãzboiului româno-român de anul trecut, pentru noi, cei de la Societatea Scriitorilor Târgoviºteni, 10 august a fost doar prilej de sãrbãtorire a lui Barbu Cioculescu, târgoviºteanul prin spirit (n. 10 august 1927, Mountrouge în Franþa), la trecerea bornei 92 din secolul personal, marcând ºi 80 de ani de la debutul sãu literar, aºa cum singur mãrturiseºte într-o recentã carte de convorbiri: Sã nu uitãm cã la Gãeºti am petrecut primii 7 ani «de acasã». Apoi aderarea la marea familie a «Litere»-lor ºi a Societãþii Scriitorilor Târgoviºteni al cãrei membru fondator sunt din 2005, membru al juriilor (de remarcat pluralul) «Moºtenirii Vãcãreºtilor», cu ºapte cãrþi editate la «Bibliotheca», sunt un târgoviºtean sadea. Întrebat în aceeaºi carte (Un veac printre cãrþi. Barbu Cioculescu în dialog cu Mihai Stan, lansatã la a VI-a ediþie a Simpozionului Naþional ªcoala de la Târgoviºte) când a debutat literar, B.C. a avansat o datã confirmatã ºi de omniscientul Nicolae Scurtu în proceeding-ul Simpozionului: în Universul copiilor, revista lui N. Batzaria (Moº Nae), nr. 51, 13 dec. 1939, adicã în urmã cu 80 de ani, aici elevul Barbu Cioculescu semnând fabula Împãratul animalelor. Chiar plasând dupã alþii debutul peste 5 ani (1944, Kalende cu poeziile Prietene! ºi Nucul, incluse în recenta antologie La Steaua Pãstorului. -

Revista Padurilor Nr. 4-5/2013

REVISTA PĂDURILOR REVISTĂ TEHNICO-ȘTIINȚIFICĂ EDITATĂ DE SOCIETATEA „PROGRESUL SILVIC” CUPRINS (Nr. 4-5 / 2013) GHEORGHE GAVRILESCU, ION I. FLORESCU : Revista pădurilor a revenit integral la Societatea Progresul Silvic . 3 Colegiul de redacție AdAm CrăCiunesCu : Anul 2014 - Anul reformei în reglementările silvice ....................................................... 6 Membri : ConstAntin roșu, Florin dănesCu : Probleme privind stațiunile forestiere prof. dr. ing. Ioan Vasile Abrudan și reconstrucția ecologică a pădurilor în contextul schimbării condițiilor de c. s. I dr. ing. Iovu-Adrian Biriș mediu (regionale și locale) în România . 11 s. l. dr. ing. Stelian Borz dr. ing. Adam Crăciunescu NECULAI MARCEL FLOCEA, BOGDAN M. NEGREA : Tehnici simplificate de prof. dr. ing. Lucian Curtu investigație dendroecologică în arborete cu molid supuse poluării generate de activități din minerit în Bucovina. Partea I - Creșterea exemplarelor conf. dr. ing. Mihai Daia mature. Aspecte metodologice și aplicații . 17 s. l. Gabriel Duduman ing. Olga Georgescu JOHANN KRUCH : Prețul buștenilor, dependent de diametrul lor median și de acad. prof. Victor Giurgiu clasa de calitate ................................................. 26 prof. dr. ing. Sergiu Horodnic MARIA ARDELEANU, BIRGIT ELANDS, ROSALIE VAN DAM : Differences in the dr. ing. Maftei Lesan Attachment to the Forest between former Collectivized and Non-collectivized dr. ing. Ion Machedon Communities in Romania ....................................... 35 dr. ing. Gheorghe Mohanu prof. dr. ing. Ion I. Florescu DORIN-IOAN RUS : Waldnutzung im Siebenbürgen des 18. Jahrhunderts dr. ing. Romica Tomescu (Folosirea pădurii în Transilvania în secolul al XVIII-lea) . 45 MAGDALENA MEDA : Evoluția fondului de producție real în arboretele parcurse Redacția : cu tăieri de transformare spre grădinărit gestionate de O. S. Văliug . 55 UMITRESCU prof. Rodica-Ludmila D VAleriu BrAșoVeAnu, AdAm Begu : Riscul poluării aerului cu compuși ing. -

Spre Anul Urmuz

c y m k Revistã de culturã ORAª REGAL Anul XII Nr. 2 (123) Februarie 2021 Spre Anul Urmuz Gheorghe PĂUN ac două mărturisiri, altfel cititorul se va mira de ce mă grăbesc să scriu despre Urmuz în februarie, cândF puteam să mai aştept puţin, pentru a ajunge în martie, Luna Urmuz, căci pe 17 ale lunii lui Mărţişor sa născut incompa rabilul scriitor, mai ales că acum două luni, în noiembrie, tot despre Urmuz (urmuzism şi urmuzologie) vorbeam. Am două expli caţii. Prima, recunosc, ţine de admiraţia, ajunsă probabil fixaţiemanie, pe care o am pentru genialul grefier, nu mă feresc deloc etichetează grosier, scot neghina deasupra de cuvântul maximal, citiţi cărţile recente grâului, apoi strigă din răsputeri că totul ale lui Lucian Costache, piteştean, ale Anei e neghină. Şi se miră… Dar, tocmai acum, Olos/Anagaia, din Baia Mare, citiţi cărţile tocmai prin asta, prin obstinaţia demolării, mai puţin recente ale lui Nicolae Balotă, pregătesc noi procente, „surprinzătoare” Constantin Cubleşan, Ion Pop (cel care a desigur, pentru U, cel care vine de la UNIRE. îngrijit o primă ediţie critică Urmuz, Schiţe (Precizare: lungul paragraf dinainte nu este şi nuvele aproape… futuriste, apărută în o adeziune la un partid, ci la o idee! Şi un 2017 la Editura Tracus Arte, Bucureşti, din comentariu la un spectacol mediocru.) care voi cita în cele ce urmează). Lam mai Iartămă, Demetrule, revin în lumea comparat cu Ion Barbu şi cu Brâncuşi: ta minunată. Revin la titlu. semnificaţie nu expresie, zborul nu aripa, cântecul cocoşului nu… e acum în doi ani, în 2023, va l doilea motiv pentru care „fug fi Anul Urmuz: 140 de ani de înspre Urmuz” este pur circum la naştere (Curtea de Argeş, 17 martieD 1883) şi 100 de ani de la sinucidere stanţial: scriu aceste rânduri la maiA puţin de două săptămâni după alegerile (Bucureşti, 23 noiembrie 1923). -

Mai Avem Un Viitor ? România La Început De Mileniu

DUPLEX Mai avem un viitor ? România la început de mileniu Mihai ªora în dialog cu Sorin Antohi Aceastã carte a apãrut cu sprijinul Ministerului Culturii. http ://www.polirom.ro © 2001 by Editura Polirom, pentru prezenta ediþie Iaºi, B-dul Copou nr. 4, P.O. BOX 266, 6600 Bucureºti, B-dul I.C. Brãtianu nr. 6, et. 7, P.O. BOX 1-728, 70700 Descrierea CIP a Bibliotecii Naþionale a României : ANTOHI, SORIN Mai avem un viitor : România la început de mileniu. / Mihai ªora în dialog cu Sorin Antohi ; cuvînt înainte de Sorin Antohi – Iaºi : Polirom, 2001 200 p. ; 21 cm – (Duplex) Index. ISBN : 973-683-771-8 I. Antohi, Sorin 323(498) Printed in ROMANIA Mai avem un viitor? România la început de mileniu 4 MIHAI ªORA MIHAI ªORA (n. 1916). Personalitate marcantã a culturii româneºti, membru fondator al Grupului pentru Dialog Social, a publicat : Du Dialogue intérieur. Fragment d’une Anthropologie Métaphysique, Gallimard, Paris, 1947 (trad. rom. de Mona Antohi ºi Sorin Antohi, Despre dialogul interior. Fragment dintr-o Antropologie Metafizicã, cu un „Cuvînt dupã o jumãtate de secol” al autorului ºi o postfaþã de Virgil Nemoianu, Humanitas, Bucureºti, 1995) ; Sarea pãmîntului. Cantatã pe douã voci despre rostul poetic, Cartea Româneascã, Bucureºti, 1978 ; A fi, a face, a avea, Cartea Româneascã, Bucureºti, 1985 ; Eu & tu & el & ea... sau dialogul generalizat, Cartea Româneascã, Bucureºti, 1990 ; Firul ierbii, Craiova, Scrisul Românesc, 1998 ; Cîteva crochiuri ºi evocãri, Scrisul Românesc, Craiova, 2000 ; Filozoficale. Filozofia ca viaþã, Editura Elion, Bucureºti, 2000. A colaborat la numeroase periodice. A tradus din teatrul lui Jean-Paul Sartre. -

Acolada Nr. 11.Pmd

ACOLADA 11 Revistă lunară de literatură şi artăăă Apare sub egida Uniunii Scriitorilor din România Editori: Societatea Literară Acolada şi Editura Pleiade Satu Mare nr. 11 (84) noiembrie 2014 (anul VIII) 24 pagini preţ: 4 lei Director general: Radu Ulmeanu ~~~ Director: Gheorghe Grigurcu Thomas Dodd: Înălţarea Magdalenei Gheorghe Grigurcu: C.D. Zeletin: O amintire cu „Groapa fără cruci” Giuseppe Tartini Barbu Cioculescu: Constantin Trandafir: Scriitori Între amici Scorpioni şi Săgetători Alex. Ştefănescu: Poezia şi Constantin Călin: Zigzaguri comedia ideii de poezie Interviul Acoladei: Simona-Grazia Dima: Poezii Cristian Teodorescu Claudia Moscovici: Imaginile lui Dumitru Augustin Doman: Thomas Dodd Comedia neagră a zilelor noastre 2 Acolada nr. 11 noiembrie 2014 Victor Ponta, un deces lamentabil Clipele dulci trăite de eroul nostru în Dubai, alături fruntea guvernului, Băsescu i-a băgat în ceaţă cu o simplă întrebare, în celebra întâlnire de prietenul său Ghiţă, vor fi oare în măsură să-l consoleze de la Cotroceni. Au picat autostrăzi, au picat o mulţime de alte proiecte care puteau pentru pierderea, prăbuşirea, mai bine zis, a tuturor poziţiilor contribui la dezgheţul, măcar modest, al economiei. Toate pentru a asigura accesul la deja câştigate, ca şi a celor pe cale de a şi le adjudeca? Trecând puterea absolută a lui Victoraş cel isteţ şi a partidului său de baroni şi baronese, muhaiele peste vechiul şi binecunoscutul refren „O fată (Daciana, de viţă cu totul aleasă de prin cocinile de porci. Costurile campaniei electorale a lui uitată la Viena) mai găseşti, dar un prieten greu”, Ponta au depăşit orice limită, ele fiind suportate din surse bugetare, iar cifra vehiculată catastrofalul sfârşit conjugat cu ruşinoasa fugă de la locul este de 3,5 miliarde de lei. -

Serie Nouă, Martie-Mai 2018

România în Marele Război Volum VI, Nr. 2 (20), Serie nouă, martie-mai 2018 1 POLIS Revista POLIS ©Facultatea de Ştiinţe Politice şi Administrative Universitatea „Petre Andrei” din Iaşi ISSN 12219762 2 România în Marele Război SUMAR EDITORIAL 5 Războiul patimilor noastre Sabin DRĂGULIN ROMÂNIA ÎN MARELE RĂZBOI Familia regală a României pe frontul Marelui Război şi al Marii 13 Uniri (1916 - 1918) Ştefania DINU Între neutralitate şi aliniere: aspecte privind 41 politica externă a României la începutul Marelui Război Hadrian GORUN România în Primul Război Mondial 53 Dan CARBARĂU Contribuţia aeronauticii militare române la realizarea şi 67 apărarea României Mari Jănel TĂNASE Participarea Marinei Române la apărarea Dobrogei 77 în timpul Primului Război Mondial Ioan DAMASCHIN Primele acţiuni militare pe Frontul din Dobrogea. 85 Bătălia de la Turtucaia şi consecinţele acesteia asupra evoluţiei militare de pe Frontul de Sud Leonida MOISE Cooperarea militară româno-rusă în anul 1916 103 Ion GIURCĂ Unirea Basarabiei cu Regatul român. 119 Studiu relativ la implicarea militarilor Alexandru OŞCA Versuch einer Rekonstruktion von Bismarcks Rolle im Ersten 131 Weltkrieg anhand von zeitgenössischen und heutigen Dokumenten Ursula OLLENDORF Les amis nécessaires : Italia e Francia nella Grande Guerra 145 Nicola NERI 3 POLIS L’«immenso esperimento» 177 Dalle trincee alla post-verità: Marc Bloch e la nascita delle fake news Fabrizio FIUME Idealul naţional şi războiul pentru Reîntregirea Neamului 193 Românesc Daniel Gheorghe VARIA Elitele politice din Transilvania 207 în realizarea Marii Uniri de la 1 decembrie 1918 Florin GRECU ,,Democratizarea” Armatei regale în procesul trecerii României 219 la regimul totalitar de stânga (1944-1947) Dănuţ Mircea CHIRIAC Mitul veşnic al panslavismului: A treia Romă 231 Florian BICHIR Aśvamedha e Costituzione: 251 il sacrificio rituale nel sultanismo politico contemporaneo Gianfranco LONGO ARHIVE România în Primul Război Mondial. -

198504 MI 04(217).Pdf

...:. ---- .... - t . - .;.-'...:• tJ'L I;(, • - • isloric DECENIILE EPOCII CEAU,ESCU de culturi • Forta motrlce a devenlrll lstortel noaatre contemporane : ... oi1ci Mircea Mu$at 2 • latorla rominllor In arta monumentali : Valeriu Buduru, Marian $tefan 7 Anul XIX Nr. 4 (21 MARTURII ALE CUL TURII �I CIVILIZATIEl ROMANE�TI aprllle 1 • Popor de nemurltorl, popor de erol : /on Popescu-Puturi ... - 5 • In Romania acum clncl mllenll. Cultura Cucutenl unlci In Europa: • • Linda Ellis 21 Red•ctor.., ContrlbuJia Rominlel Ia lnfrlngerea faaclamulul : CRimAN POPI,TEANU Gh. Zaharia, /on CuMa, Alesandru Dutu 12 ,0 tncoronare a tuturor unlrllor" : Gh. Unc 18 Un ctltor de culturi .:omineaaci - Udrltte Nisturel : Dan Horia Mazilu ' 23 1939-1941 - mlnlstrul S.U.A.. Ia Bucurettl tranamlte..• : /on Stanciu 27 NICOLAI COPOIU • Clftlgitorll concuraulul Horea 200 ..• 33 • ltlnerar prln Vasile Smarandescu ... WDOVIC DIIIBcY vetrele volevodale : 46 • in Bucureftl, acum 50 ani ... 48 • Cirtl soslte Ia redaqle ... 56 • Potta Ma- gazin istoric ... 63 • in martle 1945, Ia Berlin: Contele Bernadotte ... 35 • lntere sul pentru latorle:Bela Kopeczi .•• 39 • Documentele aecolulul XX. Moacova, 19-30 octombrle 1943. Conferlnta mlnlftrllor afacerllor externe al U.R.S.S., S.U.A. fl Marll Brltanll (Ill) .•. 40 • AHatul Italian "In pozltle de drepJI" : A. Busuioceanu, Fl. Con stantiniu •.. 52 • BartoiOIM de 181 C81• - o voce In apirarea luralnrrn p••rW lndlenllor : Eric Eustace Williams •.. 57 • Cine a foat louis VAIIRIU BUDURU Braille? : Suzanne 8/atin ..• 61 • • Imagine din calertdarul atribuit lui Quetzalcoatl, personaj istoric, dup8 (D@cum au dovedlt descoperirile arheologice, dar �� mltic, slmbolizind, in mltologia tolteca �I azteca, sub inflltl�rea �rpelui cu pene, principiul dialectic al unirii elementelor contrarii: materie-spirit, pllmint-aer, ceea ce se tlnl�te �i·oeea ce zboari. -

Gând Românesc Revistă De Cultură, Ştiinţă Şi Artă „De La Roma Venim

Gând Românesc Revistă de cultură, ştiinţă şi artă „De la Roma venim, scumpi şi iubiţi compatrioţi din Dacia Traiană. Ni se cam veştejise diploma noastră de nobleţe, limba însă ne-am păstrat-o.” MIHAI EMINESCU 2 GÂND ROMÂNESC REVISTĂ DE CULTURĂ, ŞTIINŢĂ ŞI ARTĂ Anul VIII, Nr.1 (69) MAI 2014 EDITATĂ DE ASOCIAŢIA CULTURALĂ GÂND ROMÂNESC, GÂND EUROPEAN ŞI EDITURA GENS LATI NA ALBA IULIA 3 Revistă fondată în 1933 de Ion Chinezu Fondator serie nouă: Virgil Şerbu Cisteianu Director general Director: Ironim Muntean Redactor-şef: Terezia Filip Membrii colegiului de redacţie: George Baciu Ioan Barbu Radu Vasile Chialda Aurel Dumitru Galina Furdui Vasile Frăţilă Vistian Goia Elisabeta Isanos Dorin Oaidă Viorel Pivniceru Iuliu Pârvu Anca Sîrghie Ovidiu Suciu Ciprian Iulian Şoptică Traian Vasilcău I.S.S.N.: 1843-21882 Revista este înregistrată la Biblioteca Naţională a României – Bucureşti Depozitul Legal, Legea 111//1995 modificată prin Legea/ 594/2004 4 ,, Cel mai înalt grad la care o revistă literară poate aspira este să-şi înţeleagă drept-adică în semnificaţiile esenţiale – timpul care îi este dat să trăiască şi înţelegându-l astfel. să-l poată îndruma cu autoritatea pe care numai o bună cunoaştere , o vocaţie autentică şi o reală pasiune o pot da”. ION CHINEZU ,,Niciodată nu prea mi-au plăcut revistele literare ca să fiu sincer, din pricină că ele au devenit mai devreme sau mai târziu exponentele unui grup literar. Mă şi întreb dacă o revistă literară poate să fie foarte obiectivă? Dacă chiar felul în care se face o revistă literară şi cum sânt gândite, ideea de revistă literară, este o idee obiectivă. -

Document Nr 4 TIPO.Indd

aniversări 150 DE ANI ÎN SLUJBA OAMENILOR General-maior dr. Dumitru SESERMAN1 a 23 februarie 2006, prin Ordinul ministrului teme franceze asupra Lapărării nr. M 32, ziua de 9 octombrie este părţilor elementare; teme introdusă în galeria tradiţiilor de cinstire şi sărbătorire a germane; desen liniar, părţile armelor şi specialităţilor militare ca Ziua Resurselor Umane. fi gurii omului într-un fel Actul de naştere a structurii centrale de personal a fost corect după modele date; semnat când domnitorul Alexandru Ioan Cuza a promulgat, caligrafi a, scrisoare corentă, în anul 1862, Înaltul Decret prin care Ministerul de Război, ordinară, dreaptă şi plecată. rezultat în urma unifi cării politico-administrative, era Examenul oral cuprindea organizat pe două direcţii: I-a Direcţie Personal şi Operaţii opt etape multidisciplinare: Militare şi a II-a Direcţie Administraţia Generală. cursul religios, catehism Principalele atribuţii ale Direcţiei Personal şi Operaţii elementar, limba română, Militare erau: dislocarea şi disciplina trupelor, marşurile şi limba franceză, limba manevrele, organizarea taberelor de instrucţie; recrutarea: germană, aritmetica, istoria stabilirea contingentelor, chemarea recruţilor, încorporarea şi Principatelor, geografi a. eliberarea documentelor de lăsare la vatră etc.; organizarea Dezvoltarea diferitelor componente ale administraţiei oştirii, a efectivelor şi a lucrărilor statistice; evidenţa perso nalului militare centrale şi apariţia, în timp, a unor noi arme şi armatei (registrele matricole) şi a personalului administrativ; specializări militare au făcut ca, de-a lungul existenţei sale, studierea şi modifi carea regulamentelor militare; publicarea actuala Direcţie Management Resurse Umane să parcurgă un decretelor domneşti; angajările/reangajările în armată proces continuu de schimbări de structură şi de denumire. (în timpul domniei lui Alexandru Ioan Cuza serviciul militar În toţi cei 150 de ani de existenţă, structura centrală de a devenit obligatoriu pentru toţi cetăţenii).