Information on Haliaeetus Leucocephalus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Uncorrected Proof

Policy and Practice UNCORRECTED PROOF BBarney_C011.inddarney_C011.indd 117979 99/13/2008/13/2008 44:11:24:11:24 PPMM UNCORRECTED PROOF BBarney_C011.inddarney_C011.indd 118080 99/13/2008/13/2008 44:11:24:11:24 PPMM Copy edited by Richard Beatty 11 Conservation Values from Falconry Robert E. Kenward Anatrack Ltd and IUCN-SSC European Sustainable Use Specialist Group, Wareham, UK Introduction Falconry is a type of recreational hunting. This chapter considers the conser- vation issues surrounding this practice. It provides a historical background and then discusses how falconry’s role in conservation has developed and how it could grow in the future. Falconry, as defi ned by the International Association for Falconry and Conservation of Birds of Prey (IAF), is the hunting art of taking quarry in its natural state and habitat with birds of prey. Species commonly used for hunt- ing include eagles of the genera Aquila and Hieraëtus, other ‘broad-winged’ members of the Accipitrinae including the more aggressive buzzards and their relatives, ‘short-winged’ hawks of the genus Accipiter and ‘long-winged’ falcons (genus Falco). Falconers occur in more than 60 countries worldwide, mostly in North America, the Middle East, Europe, Central Asia, Japan and southern Africa. Of these countries, 48 are members of the IAF. In the European Union falconry Recreational Hunting, Conservation and Rural Livelihoods: Science and Practice, 1st edition. Edited by B. Dickson, J. Hutton and B. Adams. © 2009 Blackwell Publishing, UNCORRECTEDISBN 978-1-4051-6785-7 (pb) and 978-1-4051-9142-5 (hb). PROOF BBarney_C011.inddarney_C011.indd 118181 99/13/2008/13/2008 44:11:24:11:24 PPMM Copy edited by Richard Beatty 182 ROBERT E. -

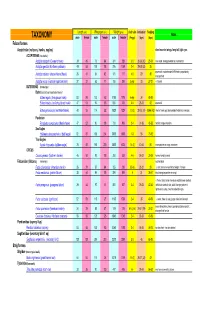

Avian Taxonomy

Length (cm) Wing span (cm) Weight (gms) cluch size incubation fledging Notes TAXONOMY male female male female male female (# eggs) (days) (days) Falconiformes Accipitridae (vultures, hawks, eagles) short rounded wings; long tail; light eyes ACCIPITRINAE (true hawks) Accipiter cooperii (Cooper's hawk) 39 45 73 84 341 528 3-5 30-36 (30) 25-34 crow sized; strongly banded tail; rounded tail Accipiter gentilis (Northern goshawk) 49 58 101 108 816 1059 2-4 28-38 (33) 35 square tail; most abundant NAM hawk; proportionaly 26 31 54 62 101 177 4-5 29 30 Accipiter striatus (sharp-shinned hawk) strongest foot Accipiter nisus (Eurasian sparrowhawk ) 37 37 62 77 150 290 5-Apr 33 27-31 Musket BUTEONINAE (broadwings) Buteo (buzzards or broad tailed hawks) Buteo regalis (ferruginous hawk) 53 59 132 143 1180 1578 6-Apr 34 45-50 Buteo lineatus (red-shouldered hawk) 47 53 96 105 550 700 3-4 28-33 42 square tail Buteo jamaicensis (red-tailed hawk) 48 55 114 122 1028 1224 1-3 (3) 28-35 (34) 42-46 (42) (Harlan' hawk spp); dark patagial featehres: immature; Parabuteo Parabuteo cuncincutus (Harris hawk) 47 52 90 108 710 890 2-4 31-36 45-50 reddish orange shoulders Sea Eagles Haliaeetus leucocephalus (bald eagle) 82 87 185 244 3000 6300 1-3 35 70-92 True Eagles Aquila chrysaetos (golden eagle) 78 82 185 220 3000 6125 1-4 (2) 40-45 50 white patches on wings: immature; CIRCUS Circus cyaneus (Northern harrier) 46 50 93 108 350 530 4-6 26-32 30-35 hovers; hunts by sound Falconidae (falcons) (longwings) notched beak Falco columbarius (American merlin) 26 29 57 64 -

Compendium of Avian Ecology

Compendium of Avian Ecology ZOL 360 Brian M. Napoletano All images taken from the USGS Patuxent Wildlife Research Center. http://www.mbr-pwrc.usgs.gov/id/framlst/infocenter.html Taxonomic information based on the A.O.U. Check List of North American Birds, 7th Edition, 1998. Ecological Information obtained from multiple sources, including The Sibley Guide to Birds, Stokes Field Guide to Birds. Nest and other images scanned from the ZOL 360 Coursepack. Neither the images nor the information herein be copied or reproduced for commercial purposes without the prior consent of the original copyright holders. Full Species Names Common Loon Wood Duck Gaviiformes Anseriformes Gaviidae Anatidae Gavia immer Anatinae Anatini Horned Grebe Aix sponsa Podicipediformes Mallard Podicipedidae Anseriformes Podiceps auritus Anatidae Double-crested Cormorant Anatinae Pelecaniformes Anatini Phalacrocoracidae Anas platyrhynchos Phalacrocorax auritus Blue-Winged Teal Anseriformes Tundra Swan Anatidae Anseriformes Anatinae Anserinae Anatini Cygnini Anas discors Cygnus columbianus Canvasback Anseriformes Snow Goose Anatidae Anseriformes Anatinae Anserinae Aythyini Anserini Aythya valisineria Chen caerulescens Common Goldeneye Canada Goose Anseriformes Anseriformes Anatidae Anserinae Anatinae Anserini Aythyini Branta canadensis Bucephala clangula Red-Breasted Merganser Caspian Tern Anseriformes Charadriiformes Anatidae Scolopaci Anatinae Laridae Aythyini Sterninae Mergus serrator Sterna caspia Hooded Merganser Anseriformes Black Tern Anatidae Charadriiformes Anatinae -

Proposals 2018-C

AOS Classification Committee – North and Middle America Proposal Set 2018-C 1 March 2018 No. Page Title 01 02 Adopt (a) a revised linear sequence and (b) a subfamily classification for the Accipitridae 02 10 Split Yellow Warbler (Setophaga petechia) into two species 03 25 Revise the classification and linear sequence of the Tyrannoidea (with amendment) 04 39 Split Cory's Shearwater (Calonectris diomedea) into two species 05 42 Split Puffinus boydi from Audubon’s Shearwater P. lherminieri 06 48 (a) Split extralimital Gracula indica from Hill Myna G. religiosa and (b) move G. religiosa from the main list to Appendix 1 07 51 Split Melozone occipitalis from White-eared Ground-Sparrow M. leucotis 08 61 Split White-collared Seedeater (Sporophila torqueola) into two species (with amendment) 09 72 Lump Taiga Bean-Goose Anser fabalis and Tundra Bean-Goose A. serrirostris 10 78 Recognize Mexican Duck Anas diazi as a species 11 87 Transfer Loxigilla portoricensis and L. violacea to Melopyrrha 12 90 Split Gray Nightjar Caprimulgus indicus into three species, recognizing (a) C. jotaka and (b) C. phalaena 13 93 Split Barn Owl (Tyto alba) into three species 14 99 Split LeConte’s Thrasher (Toxostoma lecontei) into two species 15 105 Revise generic assignments of New World “grassland” sparrows 1 2018-C-1 N&MA Classification Committee pp. 87-105 Adopt (a) a revised linear sequence and (b) a subfamily classification for the Accipitridae Background: Our current linear sequence of the Accipitridae, which places all the kites at the beginning, followed by the harpy and sea eagles, accipiters and harriers, buteonines, and finally the booted eagles, follows the revised Peters classification of the group (Stresemann and Amadon 1979). -

University of Cape Town

Exploring the breeding diet of the Black Sparrowhawk (Accipiter Melanoleucus) on the Cape Peninsula Honours research project by Bruce Baigrie Biological Sciences Department: University of Cape Town Supervised by Dr. Arjun Amar Town Cape of University Page 1 of 33 The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgementTown of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Cape Published by the University ofof Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. University Abstract This study investigates the diet of breeding Black Sparrowhawks (Accipiter melanoleucus) on the Cape Peninsula of South Africa. Macro-remains of prey were collected from below and around the vicinity of nests throughout the breeding seasons of 2012 and 2013. These prey items were then identified down to species where possible through the use of a museum reference collection. In both years 85.9% of the individual remains were those of Columbidae, which corresponds with the only other diet study on Black Sparrowhawks. Red- eyed Doves were the most common prey species, accounting for around 35% of the diet’s biomass and 45% of the prey items. Helmeted Guineafowl were also an important component of the diet for certain nests, making up on average 26.4% biomass of the diet. I found very little difference in diet between the different stages of breeding (pre-lay, incubation and nestling), despite the fact that females only contribute significantly during the nestling state and are considerably larger than the males. -

The Systematic Position of Certain Hawks in the Genus Buteo

THE AUK A QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ORNITHOLOGY VoL. 80 OCTOnER,1963 No. 4 THE SYSTEMATIC POSITION OF CERTAIN HAWKS IN THE GENUS BUTEO N•.v K. Jo•so• A•V I•s J. P•.•.T•.RS THE mostrecent authoritative work dealingwith the North and Middle AmericanFalconiformes states that the genusButeo "is sucha composite (that is, is so variablewithin its includedsubgenera) that any description of the genusas a wholewould be largelya matter of exceptionsin one or anothersubgenus of all the genericcharacters." In otherwords, the group "defiessubdivision" (Friedmann, 1950: 212-213), and it is apparentthat the existingsubgeneric classification of North Americanforms is largely subjective. The presentreport attempts to delineatewhat seemsto be a natural unit of five New World speciesof Buteo basedupon certaincommon fea- turesof plumage,proportions, distribution, and behavior.These species, hereafter referred to as the "woodlandbuteos," are the RoadsideHawk ( B. magnirostris) , Ridgway'sHawk ( B. ridgwayi) , Red-shoulderedHawk (B. lineatus),Broad-winged Hawk (B. platypterus),and Gray Hawk or Mexican Goshawk (B. nitidus). GEOG•Ar•IC A•I) ECOLOGIC D•ST•mUT•O• For purposesof discussion,the followingsynopsis of distributionof the woodlandbuteos is presented.Except whereotherwise noted, statements regardinggeographic range are basedon the Check-listof North American birds (A.O.U., 1957) and on the Distributionalcheck-list of the birds of Mexico, Part I (Friedmann et al., 1950). The Roadside Hawk occurs from Mexico to Argentina, with 16 races recognizedby Hellmayrand Conover(1949) and alsoby Peters(1931). Mexicanraces prefer open country, second-growth woods, and forestedge (Blake, 1953). In the provinceof Bocasdel Toro, Panama,Eisenmann (1957: 250) foundit to be an "edge"species. -

Accipitridae Species Tree

Accipitridae I: Hawks, Kites, Eagles Pearl Kite, Gampsonyx swainsonii ?Scissor-tailed Kite, Chelictinia riocourii Elaninae Black-winged Kite, Elanus caeruleus ?Black-shouldered Kite, Elanus axillaris ?Letter-winged Kite, Elanus scriptus White-tailed Kite, Elanus leucurus African Harrier-Hawk, Polyboroides typus ?Madagascan Harrier-Hawk, Polyboroides radiatus Gypaetinae Palm-nut Vulture, Gypohierax angolensis Egyptian Vulture, Neophron percnopterus Bearded Vulture / Lammergeier, Gypaetus barbatus Madagascan Serpent-Eagle, Eutriorchis astur Hook-billed Kite, Chondrohierax uncinatus Gray-headed Kite, Leptodon cayanensis ?White-collared Kite, Leptodon forbesi Swallow-tailed Kite, Elanoides forficatus European Honey-Buzzard, Pernis apivorus Perninae Philippine Honey-Buzzard, Pernis steerei Oriental Honey-Buzzard / Crested Honey-Buzzard, Pernis ptilorhynchus Barred Honey-Buzzard, Pernis celebensis Black-breasted Buzzard, Hamirostra melanosternon Square-tailed Kite, Lophoictinia isura Long-tailed Honey-Buzzard, Henicopernis longicauda Black Honey-Buzzard, Henicopernis infuscatus ?Black Baza, Aviceda leuphotes ?African Cuckoo-Hawk, Aviceda cuculoides ?Madagascan Cuckoo-Hawk, Aviceda madagascariensis ?Jerdon’s Baza, Aviceda jerdoni Pacific Baza, Aviceda subcristata Red-headed Vulture, Sarcogyps calvus White-headed Vulture, Trigonoceps occipitalis Cinereous Vulture, Aegypius monachus Lappet-faced Vulture, Torgos tracheliotos Gypinae Hooded Vulture, Necrosyrtes monachus White-backed Vulture, Gyps africanus White-rumped Vulture, Gyps bengalensis Himalayan -

Phylogeny, Historical Biogeography and the Evolution of Migration in Accipitrid Birds of Prey (Aves: Accipitriformes)

Ornis Hungarica 2014. 22(1): 15–35. DOI: 10.2478/orhu-2014-0008 Phylogeny, historical biogeography and the evolution of migration in accipitrid birds of prey (Aves: Accipitriformes) Jenő nagy1 & Jácint tökölyi2* Jenő Nagy & Jácint Tökölyi 2014. Phylogeny, historical biogeography and the evolution of mig ration in accipitrid birds of prey (Aves: Accipitriformes). – Ornis Hungarica 22(1): 15–35. Abstract Migration plays a fundamental part in the life of most temperate bird species. The re gu lar, largescale seasonal movements that characterize temperate migration systems appear to have originated in parallel with the postglacial northern expansion of tropical species. Migratoriness is also in- fluenced by a number of ecological factors, such as the ability to survive harsh winters. Hence, understanding the origins and evolution of migration requires integration of the biogeographic history and ecology of birds in a phylogenetic context. We used molecular dating and ancestral state reconstruction to infer the origins and evolu- tionary changes in migratory behavior and ancestral area reconstruction to investigate historical patterns of range evolution in accipitrid birds of prey (Accipitriformes). Migration evolved multiple times in birds of prey, the ear- liest of which occurred in true hawks (Accipitrinae), during the middle Miocene period, according to our analy- ses. In most cases, a tropical ancestral distribution was inferred for the nonmigratory ancestors of migratory line- ages. Results from directional evolutionary tests indicate that migration evolved in the tropics and then increased the rate of colonization of temperate habitats, suggesting that temperate species might be descendants of tropi- cal ones that dispersed into these seasonal habitats. -

Goshawk (Accipiter Gentilis): Species Assessment - Draft

Northern Goshawk (Accipiter gentilis): Species Assessment - Draft Prepared for the Grand Mesa, Uncompahgre, and Gunnison National Forest July 2005 A Species Assessment was prepared by Jim Le Fevre1 in 2004 Revised and updated by Matt Vasquez2 with contributions by Leslie Spicer2, 2005 1 Biological Science Technician (Wildlife), Paonia Ranger District 2 Biological Science Technician (Wildlife), Gunnison Ranger District Reviewed and Edited by Clay Speas, Forest Fisheries Biologist and Tom Holland, Forest Wildlife Biologist Last Revised: August 5, 2005 Page 1 of 34 Grand Mesa, Uncompahgre, and Gunnison National Forest Northern Goshawk (Accipiter gentilis) Species Assessment TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................................................5 SUMMARY OF KEY FINDINGS .......................................................................................................................5 HABITAT CRITERIA USED IN FOREST-WIDE HABITAT EVALUATION.............................................6 2001 MIS Habitat Criteria ...............................................................................................................................6 Rationale ........................................................................................................................................................6 2005 MIS Habitat Criteria ...............................................................................................................................6 -

Accipitrinae Tree

Accipitrinae: Accipiters, Harriers Gabar Goshawk, Micronisus gabar Micronisus Long-tailed Hawk, Urotriorchis macrourus Urotriorchis Dark Chanting-Goshawk, Melierax metabates ?Eastern Chanting-Goshawk, Melierax poliopterus Melierax Pale Chanting-Goshawk, Melierax canorus Lizard Buzzard, Kaupifalco monogrammicus Kaupifalco Chestnut-shouldered Goshawk, Erythrotriorchis buergersi Erythrotriorchis Red Goshawk, Erythrotriorchis radiatus Chestnut-flanked Sparrowhawk, Tachyspiza castanilius Red-chested Goshawk, Tachyspiza toussenelii African Goshawk, Tachyspiza tachiro Red-thighed Sparrowhawk, Tachyspiza erythropus Little Sparrowhawk, Tachyspiza minulla Spot-tailed Sparrowhawk, Tachyspiza trinotata Tachyspiza Japanese Sparrowhawk, Tachyspiza gularis Besra, Tachyspiza virgata ?Dwarf Sparrowhawk, Tachyspiza nana ?Vinous-breasted Sparrowhawk, Tachyspiza rhodogaster ?Rufous-necked Sparrowhawk, Tachyspiza erythrauchen Collared Sparrowhawk, Tachyspiza cirrocephala ?New Britain Sparrowhawk, Tachyspiza brachyura Variable Goshawk, Tachyspiza hiogaster ?Gray Goshawk, Tachyspiza novaehollandiae Brown Goshawk, Tachyspiza fasciata ?Moluccan Goshawk, Tachyspiza henicogramma Shikra, Tachyspiza badia Levant Sparrowhawk, Tachyspiza brevipes ?Nicobar Sparrowhawk, Tachyspiza butleri Chinese Sparrowhawk, Tachyspiza soloensis Black-mantled Goshawk, Tachyspiza melanochlamys ?Pied Goshawk, Tachyspiza albogularis ?White-bellied Goshawk, Tachyspiza haplochroa ?Fiji Goshawk, Tachyspiza rufitorques Frances’s Sparrowhawk, Tachyspiza francesiae ?Slaty-mantled Goshawk, Tachyspiza -

Checklist of the 27 Species of Birds of Prey of Quebec

Checklist of the 27 Species of Birds of Prey of Quebec As you start to observe raptors, check off the ones you see! ORDER FALCONIFORMES Family Accipitridae Subfamily Accipitrinae (Accipiter Hawks) Sharp-shinned Hawk, Épervier brun (Accipiter striatus) Cooper’s Hawk, Épervier de Cooper (Accipiter cooperii) Northern Goshawk, Autour des palombes (Accipiter gentilis) Subfamily Circinae (Harrier) Northern Harrier, Busard Saint-Martin (Circus cyaneus) Subfamily Buteoninae (Hawks and Eagles) Red-tailed Hawk, Buse à queue rousse (Buteo jamaicensis) Rough-legged Hawk, Buse pattue (Buteo lagopus) Red-shouldered Hawk, Buse à épaulettes (Buteo lineatus) Broad-winged Hawk, Petite buse (Buteo platypterus) Bald Eagle, Pygargue à tête blanche (Haliaeetus leucocephalus) Golden Eagle, Aigle royal (Aquila chrysaetos) Subfamily Pandioninae (Osprey) Osprey, Balbuzard (Pandion haliaetus) FAMILY FALCONIDAE (Caracaras and Falcons) Subfamily Falconinae (Falcons) American Kestrel, Crécerelle d’amérique (Falco sparverius) Merlin, Faucon émerillon (Falco columbarius) Perigrine Falcon, Faucon pèlerin (Falco perigrinus) Gyrfalcon, Faucon gerfaut (Falco rusticolus) ORDER CICONIIFORMES (since 1994) FAMILY CATHARTIDAE (New World Vultures) Turkey Vulture, Urubu à tête rouge (Cathartes aura) ORDER STRIGIFORMES FAMILY TYTONIDAE (Barn Owls) Barn Owl, Effraie des clochers (Tyto alba) FAMILY STRIGIDAE (Owls) Short-eared Owl, Hibou des marais (Asio flammeus) Eastern Screech-Owl, Petit-duc maculé (Otus asio) Long-eared Owl, Hibou moyen-duc (Asio otus) Great Horned Owl, Grand-duc d’amérique (Bubo virginianus) Snowy Owl, Harfang des neiges (Bubo scandiaca) Barred Owl, Chouette rayée (Strix varia) Great gray Owl, Chouette Lapone (Strix nebulosa) Boreal Owl, Nyctale de Tengmalm (Aegolius funereus) Northern Saw-whet Owl, Petite Nyctale (Aegolius acadicus) Northern Hawk-Owl, Chouette épervière (Surnia ulula) . -

A Tiny, Long-Legged Raptor from the Early Oligocene of Poland May Be the Earliest Bird-Eating Diurnal Bird of Prey

The Science of Nature (2020) 107:48 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00114-020-01703-z ORIGINAL PAPER A tiny, long-legged raptor from the early Oligocene of Poland may be the earliest bird-eating diurnal bird of prey Gerald Mayr1 & Jørn H. Hurum2 Received: 21 July 2020 /Revised: 25 September 2020 /Accepted: 28 September 2020 # The Author(s) 2020 Abstract We report a small hawk-like diurnal bird from the early Oligocene (30–31 million years ago) of Poland. Aviraptor longicrus,n. gen. et sp. is of a size comparable with the smallest extant Accipitridae. The new species is characterized by very long legs, which, together with the small size, suggest an avivorous (bird-eating) feeding behavior. Overall, the new species resembles extant sparrowhawks (Accipiter spp.) in the length proportions of the major limb bones, even though some features indicate that it convergently acquired an Accipiter-like morphology. Most specialized avivores amongst extant accipitrids belong to the taxon Accipiter and predominantly predate small forest passerines; the smallest Accipiter species also hunts hummingbirds. Occurrence of a possibly avivorous raptor in the early Oligocene of Europe is particularly notable because A. longicrus coexisted with the earliest Northern Hemispheric passerines and modern-type hummingbirds. We therefore hypothesize that the diversification of these birds towards the early Oligocene may have triggered the evolution of small-sized avivorous raptors, and the new fossil may exemplify one of the earliest examples of avian predator/prey coevolution. Keywords Accipitridae . Aves . Evolution . Fossil birds . Rupelian Introduction allies), and Accipitrinae (sparrowhawks, harriers, and allies) form a deeply nested clade.