NEWS and NOTES by Paul Hess

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Secretary Bird

Secretary Birds are Raptors, or Birds of Prey, they are distantly related to vultures and hawks! They have all of the features of a bird of prey too, including forward facing eyes for hunting, strong talons to grab their prey, and a large hooked beak for eating! Secretary Birds do fly, but they spend of most of their day hunting by walking on the ground. Their long legs are perfect to help them see over the tall grass of their Savanna habitat. Deadly Stomp Secretary Birds have two hunting strategies. They either strike with their powerful beak or they stomp the prey with their feet! They hunt small birds, mammals, and reptiles like snakes and lizards. They are even known to hunt venomous snakes! The Little Rock Zoo works with the Secretary Bird Species Survival Plan, which helps to protect this amazing species in zoos and in the wild! Want to Learn more? Check out these links and activities! Nat Geo Wild: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kQckuAwNbFs Nat Geo Kids: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7itwHJiNRz4 Kruger National Park (South Africa): http://www.krugerpark.co.za/africa_secretary_bird.html Edge of Existence (ZSL): http://www.edgeofexistence.org/species/secretarybird/ San Diego Zoo: https://animals.sandiegozoo.org/index.php/animals/secretary-bird Secretary Birds are amazing Birds of Prey that spend most of their time on the ground rather than flying to find their food! Cut out the puzzle pieces to make your very own Secretary Bird Puzzle! Photo by Karen Caster . -

A Snail Kite's Delight

Marsh Trail - Photo by Arthur Jacoby A Snail Kite’s Delight Naturalist Observations of The Marsh Trail Impoundments By Bradley Rosendorf, Education and Outreach Associate A hike around the Marsh Trail impoundments provides opportunities for Refuge guests to observe a stunning array of unique Everglades wildlife. The Refuge is an ecological gem and one of the precious jewels of the National Wildlife Refuge System. On the Marsh Trail, visitors regularly observe species such as the American alligator, white- Bradley tailed deer, Everglade Snail Kite, Sandhill Crane, Wood Stork, Glossy Ibis, Limpkin, Purple Gallinule, Pileated Woodpecker, Great Egret, Great Blue Heron, Red- shouldered Hawk and Roseate Spoonbill. There seems to be a big increase in Roseate Spoonbill activity in the area this year! In the fall and winter months, Northern Harriers can be seen, and in the spring and summer, Swallow-tailed Sandhill Cranes - David Kendall Kites are observed. Bald Eagles can also be seen, but they are very elusive. Florida bobcats are sometimes seen stalking the water’s edge for a bird to catch for dinner. The Roseate Spoonbill - Bradley sunsets are a magical sight to behold – in the Real Everglades of Palm Beach County. Every hike on the Marsh Trail offers the possibility of a surprise. At the Refuge, people from all throughout the community unite to support wildlife conservation and be inspired in nature. The Marsh Trail impoundments include 7.6 miles of hiking trail as well as the LILA area – Loxahatchee Impoundment Research Assessment – where you can learn about tree islands and Everglades restoration collaborative research. While hiking through the Marsh Trail impoundments, you can experience an Everglades landscape and habitat that reflects the greater River of Grass ecosystem. -

Merritt Island National Wildlife Refuge BIRD LIST

Merrritt Island National Wildlife Refuge U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service P.O. Box 2683 Titusville, FL 32781 http://www.fws.gov/refuge/Merritt_Island 321/861 0669 Visitor Center Merritt Island U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service 1 800/344 WILD National Wildlife Refuge March 2019 Bird List photo: James Lyon Merritt Island National Wildlife Refuge, located just Seasonal Occurrences east of Titusville, shares a common boundary with the SP - Spring - March, April, May John F. Kennedy Space Center. Its coastal location, SU - Summer - June, July, August tropic-like climate, and wide variety of habitat types FA - Fall - September, October, November contribute to Merritt Island’s diverse bird population. WN - Winter - December, January, February The Florida Ornithological Society Records Committee lists 521 species of birds statewide. To date, 359 You may see some species outside the seasons indicated species have been identified on the refuge. on this checklist. This phenomenon is quite common for many birds. However, the checklist is designed to Of special interest are breeding populations of Bald indicate the general trend of migration and seasonal Eagles, Brown Pelicans, Roseate Spoonbills, Reddish abundance for each species and, therefore, does not Egrets, and Mottled Ducks. Spectacular migrations account for unusual occurrences. of passerine birds, especially warblers, occur during spring and fall. In winter tens of thousands of Abundance Designation waterfowl may be seen. Eight species of herons and C – Common - These birds are present in large egrets are commonly observed year-round. numbers, are widespread, and should be seen if you look in the correct habitat. Tips on Birding A good field guide and binoculars provide the basic U – Uncommon - These birds are present, but because tools useful in the observation and identification of of their low numbers, behavior, habitat, or distribution, birds. -

Mississippi Kite (Ictinia Mississippiensis)

Mississippi Kite (Ictinia mississippiensis) NMPIF level: Species Conservation Concern, Level 2 (SC2) NMPIF assessment score: 15 NM stewardship responsibility: Low National PIF status: No special status New Mexico BCRs: 16, 18, 35 Primary breeding habitat(s): Urban (southeast plains) Other habitats used: Agricultural, Middle Elevation Riparian Summary of Concern Mississippi Kite is a migratory raptor that has successfully colonized urban habitats (parks, golf courses, residential neighborhoods) in the western portion of its breeding range over the last several decades. Little is known about species ecology outside of the breeding season and, despite stable or increasing populations at the periphery of its range, it remains vulnerable due to its small population size. Associated Species Cooper’s Hawk, Ring-necked Pheasant, Mourning Dove, American Robin Distribution Mississippi Kite is erratically distributed across portions of the east and southeast, the southern Great Plains, and the southwest, west to central Arizona and south to northwest Chihuahua. It is most abundant in areas of the Gulf Coast, and in the Texas and Oklahoma panhandles. The species is a long- distance migrant, wintering in Argentina, Paraguay, and perhaps other locations in South America. In New Mexico, Mississippi Kite is most common in cites and towns of the southeast plains. It is also present in the Middle Rio Grande valley north to Corrales, and the Pecos River Valley north to Fort Sumner and possibly Puerto de Luna (Parker 1999, Parmeter et al. 2002). Ecology and Habitat Requirements Mississippi Kite occupies different habitats in different parts of its range, including mature hardwood forests in the southeast, rural woodlands in mixed and shortgrass prairie in the Great Plains, and mixed riparian woodlands in the southwest. -

Birds of the East Texas Baptist University Campus with Birds Observed Off-Campus During BIOL3400 Field Course

Birds of the East Texas Baptist University Campus with birds observed off-campus during BIOL3400 Field course Photo Credit: Talton Cooper Species Descriptions and Photos by students of BIOL3400 Edited by Troy A. Ladine Photo Credit: Kenneth Anding Links to Tables, Figures, and Species accounts for birds observed during May-term course or winter bird counts. Figure 1. Location of Environmental Studies Area Table. 1. Number of species and number of days observing birds during the field course from 2005 to 2016 and annual statistics. Table 2. Compilation of species observed during May 2005 - 2016 on campus and off-campus. Table 3. Number of days, by year, species have been observed on the campus of ETBU. Table 4. Number of days, by year, species have been observed during the off-campus trips. Table 5. Number of days, by year, species have been observed during a winter count of birds on the Environmental Studies Area of ETBU. Table 6. Species observed from 1 September to 1 October 2009 on the Environmental Studies Area of ETBU. Alphabetical Listing of Birds with authors of accounts and photographers . A Acadian Flycatcher B Anhinga B Belted Kingfisher Alder Flycatcher Bald Eagle Travis W. Sammons American Bittern Shane Kelehan Bewick's Wren Lynlea Hansen Rusty Collier Black Phoebe American Coot Leslie Fletcher Black-throated Blue Warbler Jordan Bartlett Jovana Nieto Jacob Stone American Crow Baltimore Oriole Black Vulture Zane Gruznina Pete Fitzsimmons Jeremy Alexander Darius Roberts George Plumlee Blair Brown Rachel Hastie Janae Wineland Brent Lewis American Goldfinch Barn Swallow Keely Schlabs Kathleen Santanello Katy Gifford Black-and-white Warbler Matthew Armendarez Jordan Brewer Sheridan A. -

A Black Kite Milvus Migrans on the Saint Peter and Saint Paul Archipelago, Brazil

Revista Brasileira de Ornitologia, 23(1), 31-35 March 2015 A Black Kite Milvus migrans on the Saint Peter and Saint Paul Archipelago, Brazil Guilherme T. Nunes1,2,6, Lilian S. Hoffmann3, Bruno C. L. Macena4,5, Glayson A. Bencke3 and Leandro Bugoni1 1 Laboratório de Aves Aquáticas e Tartarugas Marinhas, Instituto de Ciências Biológicas, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande – FURG, CP 474, CEP 96203-900, Rio Grande, RS, Brazil. 2 Programa de Pós-Graduação em Oceanografia Biológica, Instituto de Oceanografia, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande – FURG, CP 474, CEP 96203-900, Rio Grande, RS, Brazil. 3 Museu de Ciências Naturais, Fundação Zoobotânica do Rio Grande do Sul, CEP 90690-000, Porto Alegre, RS, Brazil. 4 Laboratório de Oceanografia Pesqueira, Departamento de Pesca e Aquicultura, Universidade Federal Rural de Pernambuco – UFRPE, CEP 52171- 900, Recife, PE, Brazil. 5 Programa de Pós-Graduação em Oceanografia, Centro de Tecnologia e Geociências, Departamento de Oceanografia, Universidade Federal de Pernambuco – UFPE, CEP 50740-550, Recife, PE, Brazil. 6 Corresponding author: [email protected] Received on 17 November 2014. Accepted on 16 March 2015. ABSTRACT: The lB ack Kite Milvus migrans is a widespread migratory raptor found over much of the Old World. Vagrants have been widely recorded far from its main migratory routes. Here, we report the occurrence of a Black Kite in the Brazilian Saint Peter and Saint Paul Archipelago (SPSPA) in April/May 2014. The bird remained for 32 days in the SPSPA, disappearing at the end of the rainy season. It looked healthy for most of this period and was once seen preying on a seabird chick. -

Uncorrected Proof

Policy and Practice UNCORRECTED PROOF BBarney_C011.inddarney_C011.indd 117979 99/13/2008/13/2008 44:11:24:11:24 PPMM UNCORRECTED PROOF BBarney_C011.inddarney_C011.indd 118080 99/13/2008/13/2008 44:11:24:11:24 PPMM Copy edited by Richard Beatty 11 Conservation Values from Falconry Robert E. Kenward Anatrack Ltd and IUCN-SSC European Sustainable Use Specialist Group, Wareham, UK Introduction Falconry is a type of recreational hunting. This chapter considers the conser- vation issues surrounding this practice. It provides a historical background and then discusses how falconry’s role in conservation has developed and how it could grow in the future. Falconry, as defi ned by the International Association for Falconry and Conservation of Birds of Prey (IAF), is the hunting art of taking quarry in its natural state and habitat with birds of prey. Species commonly used for hunt- ing include eagles of the genera Aquila and Hieraëtus, other ‘broad-winged’ members of the Accipitrinae including the more aggressive buzzards and their relatives, ‘short-winged’ hawks of the genus Accipiter and ‘long-winged’ falcons (genus Falco). Falconers occur in more than 60 countries worldwide, mostly in North America, the Middle East, Europe, Central Asia, Japan and southern Africa. Of these countries, 48 are members of the IAF. In the European Union falconry Recreational Hunting, Conservation and Rural Livelihoods: Science and Practice, 1st edition. Edited by B. Dickson, J. Hutton and B. Adams. © 2009 Blackwell Publishing, UNCORRECTEDISBN 978-1-4051-6785-7 (pb) and 978-1-4051-9142-5 (hb). PROOF BBarney_C011.inddarney_C011.indd 118181 99/13/2008/13/2008 44:11:24:11:24 PPMM Copy edited by Richard Beatty 182 ROBERT E. -

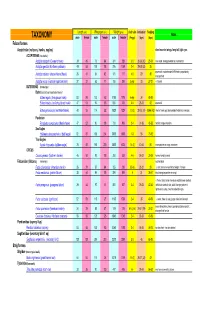

Avian Taxonomy

Length (cm) Wing span (cm) Weight (gms) cluch size incubation fledging Notes TAXONOMY male female male female male female (# eggs) (days) (days) Falconiformes Accipitridae (vultures, hawks, eagles) short rounded wings; long tail; light eyes ACCIPITRINAE (true hawks) Accipiter cooperii (Cooper's hawk) 39 45 73 84 341 528 3-5 30-36 (30) 25-34 crow sized; strongly banded tail; rounded tail Accipiter gentilis (Northern goshawk) 49 58 101 108 816 1059 2-4 28-38 (33) 35 square tail; most abundant NAM hawk; proportionaly 26 31 54 62 101 177 4-5 29 30 Accipiter striatus (sharp-shinned hawk) strongest foot Accipiter nisus (Eurasian sparrowhawk ) 37 37 62 77 150 290 5-Apr 33 27-31 Musket BUTEONINAE (broadwings) Buteo (buzzards or broad tailed hawks) Buteo regalis (ferruginous hawk) 53 59 132 143 1180 1578 6-Apr 34 45-50 Buteo lineatus (red-shouldered hawk) 47 53 96 105 550 700 3-4 28-33 42 square tail Buteo jamaicensis (red-tailed hawk) 48 55 114 122 1028 1224 1-3 (3) 28-35 (34) 42-46 (42) (Harlan' hawk spp); dark patagial featehres: immature; Parabuteo Parabuteo cuncincutus (Harris hawk) 47 52 90 108 710 890 2-4 31-36 45-50 reddish orange shoulders Sea Eagles Haliaeetus leucocephalus (bald eagle) 82 87 185 244 3000 6300 1-3 35 70-92 True Eagles Aquila chrysaetos (golden eagle) 78 82 185 220 3000 6125 1-4 (2) 40-45 50 white patches on wings: immature; CIRCUS Circus cyaneus (Northern harrier) 46 50 93 108 350 530 4-6 26-32 30-35 hovers; hunts by sound Falconidae (falcons) (longwings) notched beak Falco columbarius (American merlin) 26 29 57 64 -

Biodiversity Observations

Biodiversity Observations http://bo.adu.org.za An electronic journal published by the Animal Demography Unit at the University of Cape Town The scope of Biodiversity Observations consists of papers describing observations about biodiversity in general, including animals, plants, algae and fungi. This includes observations of behaviour, breeding and flowering patterns, distributions and range extensions, foraging, food, movement, measurements, habitat and colouration/plumage variations. Biotic interactions such as pollination, fruit dispersal, herbivory and predation fall within the scope, as well as the use of indigenous and exotic species by humans. Observations of naturalised plants and animals will also be considered. Biodiversity Observations will also publish a variety of other interesting or relevant biodiversity material: reports of projects and conferences, annotated checklists for a site or region, specialist bibliographies, book reviews and any other appropriate material. Further details and guidelines to authors are on this website. Lead Editor: Arnold van der Westhuizen – Paper Editor: Amour McCarthy and Les G Underhill INTERNET SEARCHING OF BIRD–BIRD ASSOCIATIONS: A CASE OF BEE-EATERS HITCHHIKING LARGE AFRICAN BIRDS Peter Mikula & Piotr Tryjanowski Recommended citation format: Mikula P, Tryjanowski P. 2016. Internet searching of bird–bird associations: A case of bee-eaters hitchhiking large African birds. Biodiversity Observations 7.80: 1–6. URL: http://bo.adu.org.za/content.php?id=273 Published online: 17 November 2016 – -

Estimations Relative to Birds of Prey in Captivity in the United States of America

ESTIMATIONS RELATIVE TO BIRDS OF PREY IN CAPTIVITY IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA by Roger Thacker Department of Animal Laboratories The Ohio State University Columbus, Ohio 43210 Introduction. Counts relating to birds of prey in captivity have been accomplished in some European countries; how- ever, to the knowledge of this author no such information is available in the United States of America. The following paper consistsof data related to this subject collected during 1969-1970 from surveys carried out in many different direc- tions within this country. Methods. In an attempt to obtain as clear a picture as pos- sible, counts were divided into specific areas: Research, Zoo- logical, Falconry, and Pet Holders. It became obvious as the project advanced that in some casesthere was overlap from one area to another; an example of this being a falconer working with a bird both for falconry and research purposes. In some instances such as this, the author has used his own judgment in placing birds in specific categories; in other in- stances received information has been used for this purpose. It has also become clear during this project that a count of "pets" is very difficult to obtain. Lack of interest, non-coop- eration, or no available information from animal sales firms makes the task very difficult, as unfortunately, to obtain a clear dispersal picture it is from such sourcesthat informa- tion must be gleaned. However, data related to the importa- tion of birds' of prey as recorded by the Bureau of Sport Fisheries and Wildlife is included, and it is felt some observa- tions can be made from these figures. -

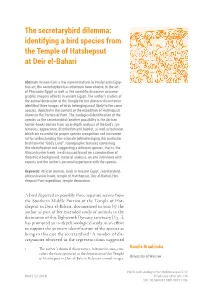

Identifying a Bird Species from the Temple of Hatshepsut at Deir El-Bahari

The secretarybird dilemma: identifying a bird species from the Temple of Hatshepsut at Deir el-Bahari Abstract: Known from a few representations in Predynastic Egyp- tian art, the secretarybird has otherwise been elusive, in the art of Pharaonic Egypt as well as the scientific discourse on icono- graphic imagery of birds in ancient Egypt. The author’s studies of the animal decoration at the Temple for her doctoral dissertation identified three images of birds belonging most likely to the same species, depicted in the context of the expedition of Hatshepsut shown in the Portico of Punt. The zoological identification of the species as the secretarybird (another possibility is the African harrier-hawk) derives from an in-depth analysis of the bird’s sys- tematics, appearance, distribution and habitat, as well as behavior, which are essential for proper species recognition and instrumen- tal for understanding the rationale behind bringing this particular bird from the “God’s Land”. Iconographic features contesting this identification and suggesting a different species, that is, the African harrier-hawk, are discussed based on a combination of theoretical background, material analysis, on-site interviews with experts and the author’s personal experience with the species. Keywords: African animals, birds in Ancient Egypt, secretarybird, African harrier-hawk, temple of Hatshepsut, Deir el-Bahari, Hat- shepsut Punt expedition, temple decoration A bird depicted in possibly three separate scenes from the Southern Middle Portico of the Temple of Hat- shepsut in Deir el-Bahari, documented in 2012 by the author as part of her extended study of animals in the decoration of this Eighteenth Dynasty sanctuary [Fig. -

Wwtworldwide

In each list below, only one bird has talons to catch its prey. Amazing Adaptations - Answers CIRCLE the bird with talons. Quiz for children aged 5-7 years 9 MALLARD DUCK MUTE SWAN OSPREY 10 MARSH HARRIER REED WARBLER CANADA GOOSE Round 1: Picture round The following birds were all featured in this week’s Amazing Adaptation Cards. Q Can you name them? Round 3: Which is the longest? In this week’s session you looked at birds that have long legs to keep their body above the water. In each list below, CIRCLE the bird that has the longest legs. If you get stuck, use your Amazing Adaptations Cards to help you. 11 REED WARBLER GREY HERON KINGFISHER © Tony Sutton© Tony @ flickr 12 LITTLE EGRET DIPPER MALLARD DUCK 1 (Mute) swan 2 (Grey) heron 3 Avocet 13 DIPPER AVOCET REED WARBLER In this week’s session you looked at birds that had long necks to reach food below the water. In each list below, CIRCLE the bird that has the longest neck. 14 MUTE SWAN OSPREY MALLARD DUCK © ianpreston @ flickr 4 (Mallard) duck 5 Dipper 15 MARSH HARRIER GREY HERON KINGFISHER Round 2: Odd one out round In this week’s session you looked at different types of feet suited to wetlands. In each list below, only one bird has webbed feet. Circle the bird with webbed feet. If you get stuck, use your Amazing Adaptations Cards to help you. Q Can you CIRCLE the odd one out in each list below? 6 REED WARBLER MUTE SWAN OSPREY The otter is a mammal and the other two are amphibians.