Uncorrected Proof

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Care and Feeding of Trained Hawks and Falcons by Jim Roush

Volume 27 | Issue 2 Article 8 1965 The aC re And Feeding Of Trained Hawks And Falcons Jim Roush Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/iowastate_veterinarian Part of the Veterinary Medicine Commons Recommended Citation Roush, Jim (1965) "The aC re And Feeding Of Trained Hawks And Falcons," Iowa State University Veterinarian: Vol. 27 : Iss. 2 , Article 8. Available at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/iowastate_veterinarian/vol27/iss2/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Iowa State University Veterinarian by an authorized editor of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Care And Feeding Of Trained Hawks And Falcons by Jim Roush Falconry is the art of training hawks, is the first few months after hatching. falcons, and eagles to pursue and capture Baby hawks are extremely frail and tender wild game. It is perhaps the oldest field and they are very susceptible to trauma sport; in fact it was one of the ways of and the forces of nature. They are also procuring meat for the table before fire very susceptible to the nutritional dis arms were developed. During the first half orders such as rickets, perosis (slipped of this century this ancient sport has in Achille's tendon) etc. Louse powders com creased in popularity. This is probably due monly used on cattle and poultry can kill to the rising standard of living and a sub them. -

Click Here for New Falconry Films Western Sporting: New Falconry Films to Our List!

CLICK HERE FOR NEW FALCONRY FILMS WESTERN SPORTING: NEW FALCONRY FILMS TO OUR LIST! FD1050 FD2045 FD2009 FD2005 HUNTING HAWKS IN ENGLAND Pastime Videos, 60 Minutes FD1048 The ancient art of falconry: hunting wild HOUSE OF GROUSE quarry with a trained hawk or falcon is SkyKing Productions, 39 Minutes FD1054 very exciting. We follow two North Steve's film-making abilities have EAGLE JOURNAL American Red-tailed Hawks and their improved greatly in the past few years! CorJo Productions, 30 minutes trainers, by day and by night, in their This is by far his greatest achievement In the USA, eagle falconry is gaining search for prey in the woods and open and it shows what is without a doubt popularity. More Golden Eagles are countryside of England. the most impressive longwing flights ever coming into the hands of falconers these There are a lot of authentic action captured on film. This new standard of days due to depredation permits. They sequences. The quarry these raptors falconry filming will set the standard on are fast, powerful raptors that can catch is primarily used as food to feed into the future. generally fly down anything in the field. not only them but numerous other All the elements of the high desert This video gives the viewer a rare hawks, owls and falcons, including many are included so we get a feel for the glimpse into the world of hunting with injured birds. They are all expertly cared wildlife, habitat, dramatic scenery as well Golden Eagles. Eagle falconer, Joe for at the Hagley Falconry & Bird as the falconry. -

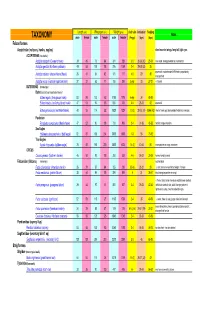

Avian Taxonomy

Length (cm) Wing span (cm) Weight (gms) cluch size incubation fledging Notes TAXONOMY male female male female male female (# eggs) (days) (days) Falconiformes Accipitridae (vultures, hawks, eagles) short rounded wings; long tail; light eyes ACCIPITRINAE (true hawks) Accipiter cooperii (Cooper's hawk) 39 45 73 84 341 528 3-5 30-36 (30) 25-34 crow sized; strongly banded tail; rounded tail Accipiter gentilis (Northern goshawk) 49 58 101 108 816 1059 2-4 28-38 (33) 35 square tail; most abundant NAM hawk; proportionaly 26 31 54 62 101 177 4-5 29 30 Accipiter striatus (sharp-shinned hawk) strongest foot Accipiter nisus (Eurasian sparrowhawk ) 37 37 62 77 150 290 5-Apr 33 27-31 Musket BUTEONINAE (broadwings) Buteo (buzzards or broad tailed hawks) Buteo regalis (ferruginous hawk) 53 59 132 143 1180 1578 6-Apr 34 45-50 Buteo lineatus (red-shouldered hawk) 47 53 96 105 550 700 3-4 28-33 42 square tail Buteo jamaicensis (red-tailed hawk) 48 55 114 122 1028 1224 1-3 (3) 28-35 (34) 42-46 (42) (Harlan' hawk spp); dark patagial featehres: immature; Parabuteo Parabuteo cuncincutus (Harris hawk) 47 52 90 108 710 890 2-4 31-36 45-50 reddish orange shoulders Sea Eagles Haliaeetus leucocephalus (bald eagle) 82 87 185 244 3000 6300 1-3 35 70-92 True Eagles Aquila chrysaetos (golden eagle) 78 82 185 220 3000 6125 1-4 (2) 40-45 50 white patches on wings: immature; CIRCUS Circus cyaneus (Northern harrier) 46 50 93 108 350 530 4-6 26-32 30-35 hovers; hunts by sound Falconidae (falcons) (longwings) notched beak Falco columbarius (American merlin) 26 29 57 64 -

When Hawks Attack: Animal-Borne Video Studies of Goshawk Pursuit

© 2015. Published by The Company of Biologists Ltd | The Journal of Experimental Biology (2015) 218, 212-222 doi:10.1242/jeb.108597 RESEARCH ARTICLE When hawks attack: animal-borne video studies of goshawk pursuit and prey-evasion strategies Suzanne Amador Kane*, Andrew H. Fulton and Lee J. Rosenthal ABSTRACT for the first time pursuit–evasion and landing behavior in the Video filmed by a camera mounted on the head of a Northern Northern Goshawk, Accipiter gentilis (Linnaeus 1758) (hereafter, Goshawk (Accipiter gentilis) was used to study how the raptor used goshawk), a large diurnal raptor (Fig. 1). Biologically derived visual guidance to pursue prey and land on perches. A combination models have inspired robotic algorithms for swarming, following of novel image analysis methods and numerical simulations of and collision avoidance (Mischiati and Krishnaprasad, 2012; mathematical pursuit models was used to determine the goshawk’s Srinivasan, 2011), and the goshawk is of special interest in this pursuit strategy. The goshawk flew to intercept targets by fixing the context because it can maneuver at high speed through cluttered prey at a constant visual angle, using classical pursuit for stationary environments (Sebesta and Baillieul, 2012). In this study, headcam prey, lures or perches, and usually using constant absolute target video was interpreted using new optical flow-based image analysis direction (CATD) for moving prey. Visual fixation was better methods that enabled us to determine which specific visual guidance maintained along the horizontal than vertical direction. In some and pursuit strategies the raptor used, while video filmed from the cases, we observed oscillations in the visual fix on the prey, ground provided complementary information on spatial trajectories. -

Compendium of Avian Ecology

Compendium of Avian Ecology ZOL 360 Brian M. Napoletano All images taken from the USGS Patuxent Wildlife Research Center. http://www.mbr-pwrc.usgs.gov/id/framlst/infocenter.html Taxonomic information based on the A.O.U. Check List of North American Birds, 7th Edition, 1998. Ecological Information obtained from multiple sources, including The Sibley Guide to Birds, Stokes Field Guide to Birds. Nest and other images scanned from the ZOL 360 Coursepack. Neither the images nor the information herein be copied or reproduced for commercial purposes without the prior consent of the original copyright holders. Full Species Names Common Loon Wood Duck Gaviiformes Anseriformes Gaviidae Anatidae Gavia immer Anatinae Anatini Horned Grebe Aix sponsa Podicipediformes Mallard Podicipedidae Anseriformes Podiceps auritus Anatidae Double-crested Cormorant Anatinae Pelecaniformes Anatini Phalacrocoracidae Anas platyrhynchos Phalacrocorax auritus Blue-Winged Teal Anseriformes Tundra Swan Anatidae Anseriformes Anatinae Anserinae Anatini Cygnini Anas discors Cygnus columbianus Canvasback Anseriformes Snow Goose Anatidae Anseriformes Anatinae Anserinae Aythyini Anserini Aythya valisineria Chen caerulescens Common Goldeneye Canada Goose Anseriformes Anseriformes Anatidae Anserinae Anatinae Anserini Aythyini Branta canadensis Bucephala clangula Red-Breasted Merganser Caspian Tern Anseriformes Charadriiformes Anatidae Scolopaci Anatinae Laridae Aythyini Sterninae Mergus serrator Sterna caspia Hooded Merganser Anseriformes Black Tern Anatidae Charadriiformes Anatinae -

New York State Falconry Guide

New York State Department of Environmental Conservation Division of Fish, Wildlife and Marine Resources New York State Falconry Guide Andrew M. Cuomo Joe Martens Governor Commissioner Table of Contents DEAR PROSPECTIVE FALCONER ................................................................................................................... 2 FROM THE NEW YORK STATE ADVISORY BOARD ......................................................................................... 4 WHAT IS FALCONRY? .................................................................................................................................... 5 HISTORY ........................................................................................................................................................ 5 THE BIRDS USED IN FALCONRY ..................................................................................................................... 5 MODERN FALCONRY ..................................................................................................................................... 6 THE COMMITMENT TO FALCONRY ............................................................................................................... 6 TWO FUNDAMENTAL REASONS FOR TAKING UP FALCONRY ....................................................................... 6 TRAINING ...................................................................................................................................................... 7 APPROXIMATE COSTS TO BE A FALCONER ................................................................................................ -

Georgia Falconry Laws and Regulations

Georgia Falconry Laws and Regulations Effective January 1, 2014, Georgia adopted the revised federal falconry regulations that the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service published in the Federal Register on October 8, 2008 ( 74 FR 64638), therefore, you are no longer required to obtain a federal falconry permit to conduct falconry. O.C.G.A. § 27-2-17 (2013) § 27-2-17. Falconry permits; duties, permitted acts, and prohibitions pertaining to permit holders (a) It shall be unlawful for any person to trap, take, transport, or possess raptors for falconry purposes unless such person possesses, in addition to any licenses and permits otherwise required by this title, a valid falconry permit as provided in Code Section27-2-23. (b) It shall be unlawful for any nonresident to trap, take, or attempt to trap or take a raptor from the wild in this state or to transport or possess any raptor in this state unless such nonresident possesses: (1) A valid falconry license or permit issued by his or her state, tribe, or territory, provided that such state, tribe, or territory has been certified by the United States Fish and Wildlife Service as compliant with applicable federal falconry law; and (2) All licenses and permits otherwise required by this title. (c) Application for a falconry permit shall be made on forms obtained from the department. (d) No falconry permit shall be issued until the applicant's raptor housing facilities and equipment have been inspected and certified by the department. (e) The department shall have the right, during reasonable times, to enter upon the premises of persons subject to this Code section to inspect and certify compliance with federal and state standards. -

Information on Haliaeetus Leucocephalus

ADW: Haliaeetus leucocephalus: Information Page I of 5 University of Michigan Museum of Zoology Structured Inquiry Searcl Home > Kingdom Animalia >- Phylum Chordata U Subphylum Vertebrata ,> Class Aves1 Order Falconiformes t- Family Accipitridae P Subfamily Accipitrinae r Species Haliaeetus leucocephalus Haliaeetusleucocephalus bald eagle Information Pictures I4-0Classification I 2008/01/20 04:31:08.826 US/Eastern By Marie S. Harris Geographic Range Kingdom: Animalia Phylum: Chordata Subphylum: Vertebrata Class: Aves Order: Falconiformes Family: Accipitridae Subfamily: Accipitrinae Genus: Haliaeetus Species: Haliaeetus leucocephallus The bald eagle is native to North America and originally bred from central Alaska and northern Canada south to Baja California, central Arizona, and the Gulf of Mexico. It now has been extirpated in many southern areas of this range. Biogeographic Regions: nearctic CL (native (k). Habitat Bald eagles are able to live anywhere on the North American continent where there are adequate nest trees, roosts ands feeding grounds. Open water such as a lake or an ocean, however, is a necessity. Terrestrial Biomnes: desert or dune Ck; savanna or grassland Q,; chaparral Q,; forest Q.; mountains Q. http://animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu/site/accounts/information/Haliaeetus-leucoceph... 1/23/2008 ADW: Haliaeetus leucocephalus: Information Page 2 of 5 Physical Description Mass 3175 g (average) [Ref] (111.76 oz) The plumage of an adult bald eagle is brown with a white head and tail. Immature eagles are irregularly mottled with white until the fourth year. Their legs are feathered half way down the tarsus, and the beak, feet, and eyes are bright yellow. Bald eagles have massive tarsi, short and powerful grasping toes, and long talons. -

Parent's Falconry Factsheet

PARENT FACTSHEET FOR FALCONERS UNDER THE AGE OF 18 So your child wants to become a falconer, what do you need to know? If you haven’t already read the “Is Falconry Right for Me” factsheet, please do so now. Why should I allow my child to become a falconer? Falconry is more than a sport; it is a way of hunting that dates back over 4,000 years. It is one of the few activities that allow a human trainer to form a hunting bond with a wild animal allowing them to participate in the capture of prey. It is a tremendous learning experience about nature, raptors, and their ecology. It is also a great way to get children outdoors in an activity that the whole family can enjoy. What is the minimum age to become a falconer? According to federal regulations, children must be at least 12 years old to become a falconer. All beginner falconers start as Apprentices; however, under Minnesota regulations, children between 12 to 16 years of age are listed as Junior Apprentices. What are my responsibilities as their parent or guardian? According to federal regulations, a parent or legal guardian must sign the permits for all children under the age of 18, and they must state that they are willing to take responsibility for all activities that occur under their child’s permit. That includes hunting and training with the raptor, as well as, care and maintenance of the raptor. Additionally, in Minnesota, Junior Apprentices (permittees that are between 12 and 16 years of age) must house their raptor in the facilities of an adult falconry permittee, preferably their parent or legal guardian; therefore, it is recommended that at least one of the parents become a falconer as well. -

Proposals 2018-C

AOS Classification Committee – North and Middle America Proposal Set 2018-C 1 March 2018 No. Page Title 01 02 Adopt (a) a revised linear sequence and (b) a subfamily classification for the Accipitridae 02 10 Split Yellow Warbler (Setophaga petechia) into two species 03 25 Revise the classification and linear sequence of the Tyrannoidea (with amendment) 04 39 Split Cory's Shearwater (Calonectris diomedea) into two species 05 42 Split Puffinus boydi from Audubon’s Shearwater P. lherminieri 06 48 (a) Split extralimital Gracula indica from Hill Myna G. religiosa and (b) move G. religiosa from the main list to Appendix 1 07 51 Split Melozone occipitalis from White-eared Ground-Sparrow M. leucotis 08 61 Split White-collared Seedeater (Sporophila torqueola) into two species (with amendment) 09 72 Lump Taiga Bean-Goose Anser fabalis and Tundra Bean-Goose A. serrirostris 10 78 Recognize Mexican Duck Anas diazi as a species 11 87 Transfer Loxigilla portoricensis and L. violacea to Melopyrrha 12 90 Split Gray Nightjar Caprimulgus indicus into three species, recognizing (a) C. jotaka and (b) C. phalaena 13 93 Split Barn Owl (Tyto alba) into three species 14 99 Split LeConte’s Thrasher (Toxostoma lecontei) into two species 15 105 Revise generic assignments of New World “grassland” sparrows 1 2018-C-1 N&MA Classification Committee pp. 87-105 Adopt (a) a revised linear sequence and (b) a subfamily classification for the Accipitridae Background: Our current linear sequence of the Accipitridae, which places all the kites at the beginning, followed by the harpy and sea eagles, accipiters and harriers, buteonines, and finally the booted eagles, follows the revised Peters classification of the group (Stresemann and Amadon 1979). -

University of Cape Town

Exploring the breeding diet of the Black Sparrowhawk (Accipiter Melanoleucus) on the Cape Peninsula Honours research project by Bruce Baigrie Biological Sciences Department: University of Cape Town Supervised by Dr. Arjun Amar Town Cape of University Page 1 of 33 The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgementTown of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Cape Published by the University ofof Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. University Abstract This study investigates the diet of breeding Black Sparrowhawks (Accipiter melanoleucus) on the Cape Peninsula of South Africa. Macro-remains of prey were collected from below and around the vicinity of nests throughout the breeding seasons of 2012 and 2013. These prey items were then identified down to species where possible through the use of a museum reference collection. In both years 85.9% of the individual remains were those of Columbidae, which corresponds with the only other diet study on Black Sparrowhawks. Red- eyed Doves were the most common prey species, accounting for around 35% of the diet’s biomass and 45% of the prey items. Helmeted Guineafowl were also an important component of the diet for certain nests, making up on average 26.4% biomass of the diet. I found very little difference in diet between the different stages of breeding (pre-lay, incubation and nestling), despite the fact that females only contribute significantly during the nestling state and are considerably larger than the males. -

The Systematic Position of Certain Hawks in the Genus Buteo

THE AUK A QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ORNITHOLOGY VoL. 80 OCTOnER,1963 No. 4 THE SYSTEMATIC POSITION OF CERTAIN HAWKS IN THE GENUS BUTEO N•.v K. Jo•so• A•V I•s J. P•.•.T•.RS THE mostrecent authoritative work dealingwith the North and Middle AmericanFalconiformes states that the genusButeo "is sucha composite (that is, is so variablewithin its includedsubgenera) that any description of the genusas a wholewould be largelya matter of exceptionsin one or anothersubgenus of all the genericcharacters." In otherwords, the group "defiessubdivision" (Friedmann, 1950: 212-213), and it is apparentthat the existingsubgeneric classification of North Americanforms is largely subjective. The presentreport attempts to delineatewhat seemsto be a natural unit of five New World speciesof Buteo basedupon certaincommon fea- turesof plumage,proportions, distribution, and behavior.These species, hereafter referred to as the "woodlandbuteos," are the RoadsideHawk ( B. magnirostris) , Ridgway'sHawk ( B. ridgwayi) , Red-shoulderedHawk (B. lineatus),Broad-winged Hawk (B. platypterus),and Gray Hawk or Mexican Goshawk (B. nitidus). GEOG•Ar•IC A•I) ECOLOGIC D•ST•mUT•O• For purposesof discussion,the followingsynopsis of distributionof the woodlandbuteos is presented.Except whereotherwise noted, statements regardinggeographic range are basedon the Check-listof North American birds (A.O.U., 1957) and on the Distributionalcheck-list of the birds of Mexico, Part I (Friedmann et al., 1950). The Roadside Hawk occurs from Mexico to Argentina, with 16 races recognizedby Hellmayrand Conover(1949) and alsoby Peters(1931). Mexicanraces prefer open country, second-growth woods, and forestedge (Blake, 1953). In the provinceof Bocasdel Toro, Panama,Eisenmann (1957: 250) foundit to be an "edge"species.