The Systematic Position of Certain Hawks in the Genus Buteo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Extreme Variation in the Tails of Adult Harlan’S Hawks

EXTREME VARIATION IN THE TAILS OF ADULT HARLAN’S HAWKS William S. (Bill) Clark Some adult Harlan’s Hawks have tails somewhat similar to this one Bob Dittrick But many others have very different tails, both in color and in markings Harlan’s Hawk type specimen. Audubon collected this adult in 1830 in Louisiana (USA) and described it as Harlan’s Buzzard or Black Warrier - Buteo harlani It is a dark morph, the common morph for this taxon. British Museum of Natural History, Tring Harlan’s Hawk Range They breed in Alaska, Yukon, & ne British Columbia & winter over much of North America. It occurs in two color morphs, dark and light. The AOS considers Harlan’s Hawk a subspecies of Red- tailed Hawk, Buteo jamaicensis harlani, but my paper in Zootaxa advocates it as a species. Clark (2018) Taxonomic status of Harlan’s Hawk Buteo jamaicensis harlani (Aves: Accipitriformes) Zootaxa concludes: “It [Harlan’s Hawk] should be considered a full species based on lack of justification for considering it a subspecies, and the many differences between it and B. jamaicensis, which are greater than differences between any two subspecies of diurnal raptor.” Harlan’s Hawk is a species: 1. Lack of taxonomic justification for inclusion with Buteo jamaicensis. 2. Differs from Buteo jamaicensis by: * Frequency of color morphs; * Adult plumages by color morph, especially in tail pattern and color; * Neotony: Harlan’s adult & juvenile body plumages are almost alike; whereas those of Red-tails differ. * Extent of bare area on the tarsus. * Some behaviors. TYPE SPECIMEN - Upper tail is medium gray, with a hint of rufous and some speckling, wavy banding on one feather, & wide irregular subterminal band. -

Predation of Birds Trapped in Mist Nets by Raptors in the Brazilian Caatinga

Predation of Birds Trapped in Mist Nets by Raptors in the Brazilian Caatinga 1 2 5 Juan Ruiz-Esparza • • Resumen: 1 3 Patricio Adriano da Rocha • La red de neb/ina es una tecnica de captura de Adauto de Souza Ribeiro4 vertebrados voladores como aves y murcielagos. Una Stephen F. Ferrari4 vez capturados e inmovilizados, los animates son 1 Graduate Program in Ecology and Conservation, vulnerables a ataques par predadores hasta su extracci6n. Ataques de animates atrapados han sido Universidade Federal de Sergipe, Avenida registrados en diferentes lugares, aunque los datos son Marechal Rondon s/n, 49.100-000 Sao poco sistematicos, tales como clasificaci6n de la Crist6vao - Sergipe, Brazil. depredaci6n estrin disponibles. Analizamos ataques 2 PR D MA , Universidade Federal de Sergipe, contra las aves capturadas en redes de neblina en la Av. Marechal Rondon s/n, 49.100-000 Caatinga y regiones aledafias en el nordeste de Brasil. Sao Crist6vao-Sergipe, Brazil. Un total de 979 aves fueron capturadas durante 6, 000 horas-red de muestreo, donde 18 (1, 8%) fueron 3 Graduate Program in Zoot gy, U n:i versidade encontradas muertas en Ia red de neblina con senates de Federal da Paraiba, Joao Pessoa-Paraiba, Brazil. Ia depredaci6n. En Ia mayoria de los casas no fue posible identificar el predador, un Gavilan de los 4 Department of Biology, Unjversidade Fed ral d Caminos (Rupomis magnirostris) fue capturado junto S r0 ipe, A venida Marechal Rondon con un Chivi Amarillento (Basileuterus flaveolus) /n 49.100-000 Sao Crist6vao- Sergipe Brazil. depredado, heridas simi/ares fueron observadas en las 5 orresponding author; e-maiJ: otras aves, sugiriendo que rapaces pudieron haber sido juanco lorad 2 1@ h tmail.com responsables par los otros ataques. -

Uncorrected Proof

Policy and Practice UNCORRECTED PROOF BBarney_C011.inddarney_C011.indd 117979 99/13/2008/13/2008 44:11:24:11:24 PPMM UNCORRECTED PROOF BBarney_C011.inddarney_C011.indd 118080 99/13/2008/13/2008 44:11:24:11:24 PPMM Copy edited by Richard Beatty 11 Conservation Values from Falconry Robert E. Kenward Anatrack Ltd and IUCN-SSC European Sustainable Use Specialist Group, Wareham, UK Introduction Falconry is a type of recreational hunting. This chapter considers the conser- vation issues surrounding this practice. It provides a historical background and then discusses how falconry’s role in conservation has developed and how it could grow in the future. Falconry, as defi ned by the International Association for Falconry and Conservation of Birds of Prey (IAF), is the hunting art of taking quarry in its natural state and habitat with birds of prey. Species commonly used for hunt- ing include eagles of the genera Aquila and Hieraëtus, other ‘broad-winged’ members of the Accipitrinae including the more aggressive buzzards and their relatives, ‘short-winged’ hawks of the genus Accipiter and ‘long-winged’ falcons (genus Falco). Falconers occur in more than 60 countries worldwide, mostly in North America, the Middle East, Europe, Central Asia, Japan and southern Africa. Of these countries, 48 are members of the IAF. In the European Union falconry Recreational Hunting, Conservation and Rural Livelihoods: Science and Practice, 1st edition. Edited by B. Dickson, J. Hutton and B. Adams. © 2009 Blackwell Publishing, UNCORRECTEDISBN 978-1-4051-6785-7 (pb) and 978-1-4051-9142-5 (hb). PROOF BBarney_C011.inddarney_C011.indd 118181 99/13/2008/13/2008 44:11:24:11:24 PPMM Copy edited by Richard Beatty 182 ROBERT E. -

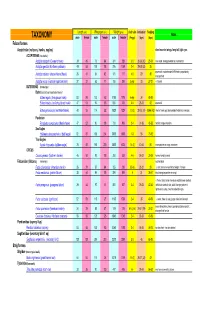

Avian Taxonomy

Length (cm) Wing span (cm) Weight (gms) cluch size incubation fledging Notes TAXONOMY male female male female male female (# eggs) (days) (days) Falconiformes Accipitridae (vultures, hawks, eagles) short rounded wings; long tail; light eyes ACCIPITRINAE (true hawks) Accipiter cooperii (Cooper's hawk) 39 45 73 84 341 528 3-5 30-36 (30) 25-34 crow sized; strongly banded tail; rounded tail Accipiter gentilis (Northern goshawk) 49 58 101 108 816 1059 2-4 28-38 (33) 35 square tail; most abundant NAM hawk; proportionaly 26 31 54 62 101 177 4-5 29 30 Accipiter striatus (sharp-shinned hawk) strongest foot Accipiter nisus (Eurasian sparrowhawk ) 37 37 62 77 150 290 5-Apr 33 27-31 Musket BUTEONINAE (broadwings) Buteo (buzzards or broad tailed hawks) Buteo regalis (ferruginous hawk) 53 59 132 143 1180 1578 6-Apr 34 45-50 Buteo lineatus (red-shouldered hawk) 47 53 96 105 550 700 3-4 28-33 42 square tail Buteo jamaicensis (red-tailed hawk) 48 55 114 122 1028 1224 1-3 (3) 28-35 (34) 42-46 (42) (Harlan' hawk spp); dark patagial featehres: immature; Parabuteo Parabuteo cuncincutus (Harris hawk) 47 52 90 108 710 890 2-4 31-36 45-50 reddish orange shoulders Sea Eagles Haliaeetus leucocephalus (bald eagle) 82 87 185 244 3000 6300 1-3 35 70-92 True Eagles Aquila chrysaetos (golden eagle) 78 82 185 220 3000 6125 1-4 (2) 40-45 50 white patches on wings: immature; CIRCUS Circus cyaneus (Northern harrier) 46 50 93 108 350 530 4-6 26-32 30-35 hovers; hunts by sound Falconidae (falcons) (longwings) notched beak Falco columbarius (American merlin) 26 29 57 64 -

Human-Wildlife Conflicts in the Southern Yungas

animals Article Human-Wildlife Conflicts in the Southern Yungas: What Role do Raptors Play for Local Settlers? Amira Salom 1,2,3,*, María Eugenia Suárez 4 , Cecilia Andrea Destefano 5, Joaquín Cereghetti 6, Félix Hernán Vargas 3 and Juan Manuel Grande 3,7 1 Laboratorio de Ecología y Conservación de Vida Silvestre, Centro Austral de Investigaciones Científicas (CADIC-CONICET), Bernardo Houssay 200, Ushuaia 9410, Argentina 2 Departamento de Ecología, Genética y Evolución, Facultad de Ciencias Exactas y Naturales, Universidad de Buenos Aires, Intendente Güiraldes 2160, Buenos Aires C1428EGA, Argentina 3 The Peregrine Fund, 5668 West Flying Hawk Lane, Boise, ID 83709, USA; [email protected] (F.H.V.); [email protected] (J.M.G.) 4 Grupo de Etnobiología, Departamento de Biodiversidad y Biología Experimental, Facultad de Ciencias Exactas y Naturales, e Instituto de Micología y Botánica (INMIBO), Universidad de Buenos Aires, CONICET-UBA, Intendente Güiraldes 2160, Buenos Aires C1428EGA, Argentina; [email protected] 5 Área de Agroecología, Facultad de Agronomía, Universidad de Buenos Aires, Av. San Martín 4453, Buenos Aires C1417, Argentina; [email protected] 6 Las Jarillas 83, Santa Rosa 6300, Argentina; [email protected] 7 Colaboratorio de Biodiversidad, Ecología y Conservación (ColBEC), INCITAP (CONICET-UNLPam), Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas, Facultad de Ciencias Exactas y Naturales (FCEyN), Universidad Nacional de La Pampa (UNLPam), Avda, Uruguay 151, Santa Rosa 6300, Argentina * Correspondence: [email protected] Simple Summary: Human-Wildlife conflict (HWC) has become an important threat producing Citation: Salom, A.; Suárez, M.E.; biodiversity loss around the world. As conflictive situations highly depend on their unique socio- Destefano, C.A.; Cereghetti, J.; Vargas, ecological context, evaluation of the different aspects of the human dimension of conflicts is crucial to F.H.; Grande, J.M. -

Compendium of Avian Ecology

Compendium of Avian Ecology ZOL 360 Brian M. Napoletano All images taken from the USGS Patuxent Wildlife Research Center. http://www.mbr-pwrc.usgs.gov/id/framlst/infocenter.html Taxonomic information based on the A.O.U. Check List of North American Birds, 7th Edition, 1998. Ecological Information obtained from multiple sources, including The Sibley Guide to Birds, Stokes Field Guide to Birds. Nest and other images scanned from the ZOL 360 Coursepack. Neither the images nor the information herein be copied or reproduced for commercial purposes without the prior consent of the original copyright holders. Full Species Names Common Loon Wood Duck Gaviiformes Anseriformes Gaviidae Anatidae Gavia immer Anatinae Anatini Horned Grebe Aix sponsa Podicipediformes Mallard Podicipedidae Anseriformes Podiceps auritus Anatidae Double-crested Cormorant Anatinae Pelecaniformes Anatini Phalacrocoracidae Anas platyrhynchos Phalacrocorax auritus Blue-Winged Teal Anseriformes Tundra Swan Anatidae Anseriformes Anatinae Anserinae Anatini Cygnini Anas discors Cygnus columbianus Canvasback Anseriformes Snow Goose Anatidae Anseriformes Anatinae Anserinae Aythyini Anserini Aythya valisineria Chen caerulescens Common Goldeneye Canada Goose Anseriformes Anseriformes Anatidae Anserinae Anatinae Anserini Aythyini Branta canadensis Bucephala clangula Red-Breasted Merganser Caspian Tern Anseriformes Charadriiformes Anatidae Scolopaci Anatinae Laridae Aythyini Sterninae Mergus serrator Sterna caspia Hooded Merganser Anseriformes Black Tern Anatidae Charadriiformes Anatinae -

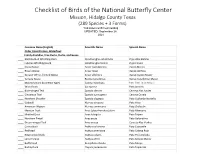

Bird Checklist

Checklist of Birds of the National Butterfly Center Mission, Hidalgo County Texas (289 Species + 3 Forms) *indicates confirmed nesting UPDATED: September 28, 2021 Common Name (English) Scientific Name Spanish Name Order Anseriformes, Waterfowl Family Anatidae, Tree Ducks, Ducks, and Geese Black-bellied Whistling-Duck Dendrocygna autumnalis Pijije Alas Blancas Fulvous Whistling-Duck Dendrocygna bicolor Pijije Canelo Snow Goose Anser caerulescens Ganso Blanco Ross's Goose Anser rossii Ganso de Ross Greater White-fronted Goose Anser albifrons Ganso Careto Mayor Canada Goose Branta canadensis Ganso Canadiense Mayor Muscovy Duck (Domestic type) Cairina moschata Pato Real (doméstico) Wood Duck Aix sponsa Pato Arcoíris Blue-winged Teal Spatula discors Cerceta Alas Azules Cinnamon Teal Spatula cyanoptera Cerceta Canela Northern Shoveler Spatula clypeata Pato Cucharón Norteño Gadwall Mareca strepera Pato Friso American Wigeon Mareca americana Pato Chalcuán Mexican Duck Anas (platyrhynchos) diazi Pato Mexicano Mottled Duck Anas fulvigula Pato Tejano Northern Pintail Anas acuta Pato Golondrino Green-winged Teal Anas crecca Cerceta Alas Verdes Canvasback Aythya valisineria Pato Coacoxtle Redhead Aythya americana Pato Cabeza Roja Ring-necked Duck Aythya collaris Pato Pico Anillado Lesser Scaup Aythya affinis Pato Boludo Menor Bufflehead Bucephala albeola Pato Monja Ruddy Duck Oxyura jamaicensis Pato Tepalcate Order Galliformes, Upland Game Birds Family Cracidae, Guans and Chachalacas Plain Chachalaca Ortalis vetula Chachalaca Norteña Family Odontophoridae, -

Comparative Phylogeography and Population Genetics Within Buteo Lineatus Reveals Evidence of Distinct Evolutionary Lineages

Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 49 (2008) 988–996 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ympev Comparative phylogeography and population genetics within Buteo lineatus reveals evidence of distinct evolutionary lineages Joshua M. Hull a,*, Bradley N. Strobel b, Clint W. Boal b, Angus C. Hull c, Cheryl R. Dykstra d, Amanda M. Irish a, Allen M. Fish c, Holly B. Ernest a,e a Wildlife and Ecology Unit, Veterinary Genetics Laboratory, 258 CCAH, University of California, One Shields Avenue, Davis, CA 95616, USA b U.S. Geological Survey Texas Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit, Department of Natural Resources Management, Texas Tech University, Lubbock, TX 79409, USA c Golden Gate Raptor Observatory, Building 1064 Fort Cronkhite, Sausalito, CA 94965, USA d Raptor Environmental, 7280 Susan Springs Drive, West Chester, OH 45069, USA e Department of Population Health and Reproduction, School of Veterinary Medicine, University of California, One Shields Avenue/Old Davis Road, Davis, CA 95616, USA article info abstract Article history: Traditional subspecies classifications may suggest phylogenetic relationships that are discordant with Received 25 June 2008 evolutionary history and mislead evolutionary inference. To more accurately describe evolutionary rela- Revised 13 September 2008 tionships and inform conservation efforts, we investigated the genetic relationships and demographic Accepted 17 September 2008 histories of Buteo lineatus subspecies in eastern and western North America using 21 nuclear microsatel- Available online 26 September 2008 lite loci and 375-base pairs of mitochondrial control region sequence. Frequency based analyses of mito- chondrial sequence data support significant population distinction between eastern (B. -

Diurnal Birds of Prey of Belize

DIURNAL BIRDS OF PREY OF BELIZE Nevertheless, we located thirty-four active Osprey by Dora Weyer nests, all with eggs or young. The average number was three per nest. Henry Pelzl, who spent the month The Accipitridae of June, 1968, studying birds on the cayes, estimated 75 Belize is a small country south of the Yucatán to 100 pairs offshore. Again, he could not get to many Peninsula on the Caribbean Sea. Despite its small of the outer cayes. It has been reported that the size, 285 km long and 112 km wide (22 963 km2), southernmost part of Osprey range here is at Belize encompasses a great variety of habitats: Dangriga (formerly named Stann Creek Town), a mangrove cays and coastal forests, lowland tropical little more than halfway down the coast. On Mr pine/oak/palm savannas (unique to Belize, Honduras Knoder’s flight we found Osprey nesting out from and Nicaragua), extensive inland marsh, swamp and Punta Gorda, well to the south. lagoon systems, subtropical pine forests, hardwood Osprey also nest along some of the rivers inland. Dr forests ranging from subtropical dry to tropical wet, Stephen M. Russell, author of A Distributional Study and small areas of elfin forest at the top of the highest of the Birds of British Honduras, the only localized peaks of the Maya Mountains. These mountains are reference, in 1963, suspects that most of the birds seen built of extremely old granite overlaid with karst inland are of the northern race, carolinensis, which limestone. The highest is just under 1220 m. Rainfall winters here. -

DO NOT Miss This GREAT Opportunity LIMITED SPACE to 10 PEOPLE

THE VERACRUZ RIVER OF RAPTORS PROJECT RAPTORS IDENTIFICATION-COUNTING COURSE MARCH 2017 The Veracruz River of Raptors © Pronatura Veracruz; Laughing Falcon © Pronatura Veracruz March 20 to March 30, 2017 DO NOT miss this GREAT opportunity Fee $1,800 USD (Include housing and food and local transportation) LIMITED SPACE TO 10 PEOPLE The Pronatura Veracruz River of Raptors program witnesses the greatest migration spectacle on Earth. Every fall, in central Veracruz Mexico, an average of four and a half million raptors from over 25 species have been counted in Pronatura´s monitoring stations in their southward migratory journey! On a good day, over 100,000 migratory raptors and vultures can cover the skies; but, during a Big Day, over 500,000 have been count! During the spring migration we have the opportunity to see the migration northward, although, the numbers are not comparable with the numbers in the Fall, it brings the opportunity to learn how to identify the following Raptors: (Osprey, Swainson´s Hawk, Broad-winged Hawk, Ret-tailed Hawk, Zone-Tailed Hawk, Gray Hawk, Roadside Hawk, Short-tailed Hawk, Cooper´s Hawk, Sharp- shined Hawk, Common-black Hawk, Black-collared Hawk, Peregrine Falcon, American Kestrel, Laughing Falcon, Bat Falcon, Aplomado Falcon, Crested Caracara, Northern Harrier, Hook-billed Kite, Mississippi Kite, Swallow-tailed Kite, Snail Kite, Turkey Vulture and Black Vulture). The observation location, encounters the same species and the same flight behavior as in the fall, so participants, will be able to gradually get the skill to count and identify a wide variety of raptors and also learn to estimate large flocks of raptors (some lines can have 10 thousand raptors and cross the sky in less than 10 minutes) similar the way that the counters from the Veracruz River of Raptors count during the fall. -

Breeding Biology of Neotropical Accipitriformes: Current Knowledge and Research Priorities

Revista Brasileira de Ornitologia 26(2): 151–186. ARTICLE June 2018 Breeding biology of Neotropical Accipitriformes: current knowledge and research priorities Julio Amaro Betto Monsalvo1,3, Neander Marcel Heming2 & Miguel Ângelo Marini2 1 Programa de Pós-graduação em Ecologia, IB, Universidade de Brasília, Brasília, DF, Brazil. 2 Departamento de Zoologia, IB, Universidade de Brasília, Brasília, DF, Brazil. 3 Corresponding author: [email protected] Received on 08 March 2018. Accepted on 20 July 2018. ABSTRACT: Despite the key role that knowledge on breeding biology of Accipitriformes plays in their management and conservation, survey of the state-of-the-art and of information gaps spanning the entire Neotropics has not been done since 1995. We provide an updated classification of current knowledge about breeding biology of Neotropical Accipitridae and define the taxa that should be prioritized by future studies. We analyzed 440 publications produced since 1995 that reported breeding of 56 species. There is a persistent scarcity, or complete absence, of information about the nests of eight species, and about breeding behavior of another ten. Among these species, the largest gap of breeding data refers to the former “Leucopternis” hawks. Although 66% of the 56 evaluated species had some improvement on knowledge about their breeding traits, research still focus disproportionately on a few regions and species, and the scarcity of breeding data on many South American Accipitridae persists. We noted that analysis of records from both a citizen science digital database and museum egg collections significantly increased breeding information on some species, relative to recent literature. We created four groups of priority species for breeding biology studies, based on knowledge gaps and threat categories at global level. -

Ferruginous Hawk (Buteo Regalis)

COSEWIC Assessment and Update Status Report on the Ferruginous Hawk Buteo regalis in Canada THREATENED 2008 COSEWIC status reports are working documents used in assigning the status of wildlife species suspected of being at risk. This report may be cited as follows: COSEWIC. 2008. COSEWIC assessment and update status report on the Ferruginous Hawk Buteo regalis in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. vii + 24 pp. (www.sararegistry.gc.ca/status/status_e.cfm). Previous reports: Schmutz, K. J. 1995. COSEWIC update status report on the Ferruginous Hawk Buteo regalis in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. 1-15 pp. Schmutz, K. J. 1980. COSEWIC status report on the Ferruginous Hawk Buteo regalis in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. 1-25 pp. Production note: COSEWIC would like to acknowledge David A. Kirk and Jennie L. Pearce for writing the update status report on the Ferruginous Hawk, Buteo regalis, prepared under contract with Environment Canada. The report was overseen and edited by Richard Cannings, COSEWIC Birds Specialist Subcommittee Co- chair. For additional copies contact: COSEWIC Secretariat c/o Canadian Wildlife Service Environment Canada Ottawa, ON K1A 0H3 Tel.: 819-953-3215 Fax: 819-994-3684 E-mail: COSEWIC/[email protected] http://www.cosewic.gc.ca Également disponible en français sous le titre Ếvaluation et Rapport de situation du COSEPAC sur la buse rouilleuse (Buteo regalis) au Canada – Mise à jour. Cover illustration: Ferruginous Hawk — Photo by Dr. Gordon Court. Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, 2008.