University of Cape Town

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Melagiris (Tamil Nadu)

MELAGIRIS (TAMIL NADU) PROPOSAL FOR IMPORTANT BIRD AREA (IBA) State : Tamil Nadu, India District : Krishnagiri, Dharmapuri Coordinates : 12°18©54"N 77°41©42"E Ownership : State Area : 98926.175 ha Altitude : 300-1395 m Rainfall : 620-1000 mm Temperature : 10°C - 35°C Biographic Zone : Deccan Peninsula Habitats : Tropical Dry Deciduous, Riverine Vegetation, Tropical Dry Evergreen Proposed Criteria A1 (Globally Threatened Species) A2 (Endemic Bird Area 123 - Western Ghats, Secondary Area s072 - Southern Deccan Plateau) A3 (Biome-10 - Indian Peninsula Tropical Moist Forest, Biome-11 - Indo-Malayan Tropical Dry Zone) GENERAL DESCRIPTION The Melagiris are a group of hills lying nestled between the Cauvery and Chinnar rivers, to the south-east of Hosur taluk in Tamil Nadu, India. The Melagiris form part of an almost unbroken stretch of forests connecting Bannerghatta National Park (which forms its north-western boundary) to the forests of Cauvery Wildlife Sanctuary - Karnataka (which forms its southern boundary, separated by the river Cauvery), and further to Biligirirangan hills and Sathyamangalam forests. The northern and western parts are comparatively plain and is part of the Mysore plateau. The average elevation in this region is 500-1000 m. Ground sinks to 300m in the valley of the Cauvery and the highest point is the peak of Guthereyan at 1395.11 m. Red sandy loam is the most common soil type found in this region. Small deposits of alluvium are found along Cauvery and Chinnar rivers and Kaoline is found in some areas near Jowlagiri. The temperature ranges from 10°C ± 35°C. South-west monsoon is fairly active mostly in the northern areas, but north-east monsoon is distinctly more effective in the region. -

South Africa: Magoebaskloof and Kruger National Park Custom Tour Trip Report

SOUTH AFRICA: MAGOEBASKLOOF AND KRUGER NATIONAL PARK CUSTOM TOUR TRIP REPORT 24 February – 2 March 2019 By Jason Boyce This Verreaux’s Eagle-Owl showed nicely one late afternoon, puffing up his throat and neck when calling www.birdingecotours.com [email protected] 2 | TRIP REPORT South Africa: Magoebaskloof and Kruger National Park February 2019 Overview It’s common knowledge that South Africa has very much to offer as a birding destination, and the memory of this trip echoes those sentiments. With an itinerary set in one of South Africa’s premier birding provinces, the Limpopo Province, we were getting ready for a birding extravaganza. The forests of Magoebaskloof would be our first stop, spending a day and a half in the area and targeting forest special after forest special as well as tricky range-restricted species such as Short-clawed Lark and Gurney’s Sugarbird. Afterwards we would descend the eastern escarpment and head into Kruger National Park, where we would make our way to the northern sections. These included Punda Maria, Pafuri, and the Makuleke Concession – a mouthwatering birding itinerary that was sure to deliver. A pair of Woodland Kingfishers in the fever tree forest along the Limpopo River Detailed Report Day 1, 24th February 2019 – Transfer to Magoebaskloof We set out from Johannesburg after breakfast on a clear Sunday morning. The drive to Polokwane took us just over three hours. A number of birds along the way started our trip list; these included Hadada Ibis, Yellow-billed Kite, Southern Black Flycatcher, Village Weaver, and a few brilliant European Bee-eaters. -

Avian Poxvirus in a Free-Range Juvenile Speckled (Rock) Pigeon (Columba Guinea)

Page 1 of 4 Case Report Avian poxvirus in a free-range juvenile speckled (rock) pigeon (Columba guinea) Authors: A flightless wild juvenile rock pigeon Columba( guinea) with pox-like lesions was picked up on 1 Dauda G. Bwala the premises of the Faculty of Veterinary Science, University of Pretoria, Onderstepoort. The Folorunso O. Fasina2 Neil M. Duncan3 pigeon was housed overnight for possible treatment the following day but died before any other intervention could be instituted. At necropsy, coalescing masses of yellowish nodular Affiliations: cutaneous tumour-like lesions principally on the featherless areas were noticed on the dead 1 Poultry Reference Centre, pigeon’s head as well as the beak. Histological examination of the sampled skin lesions revealed Department of Production multifocal areas of hypertrophic and hyperplastic epidermal epithelial cells with eosinophilic Animal Studies, University of Pretoria, South Africa intracytoplasmic inclusion bodies (Bollinger bodies). Extract from the lesion was processed and inoculated on the chorioallantoic membranes (CAM) of 11-day-old embryonated chicken eggs 2Department of Production and this produced pocks on one of the CAM at day 7 post-inoculation. Electron microscopy Animal Studies, University of confirmed the presence of poxvirus in the CAM with the pock lesions. Pretoria, South Africa 3Pathology Section, Department of Paraclinical Sciences, University of Introduction Pretoria, South Africa Avian pox is a cutaneous condition in birds that is characterised by raised, wart-like lesions, Correspondence to: mainly on the featherless portions of the skin. It is a common and well-known disease of chickens, Folorunso Fasina turkeys, pet and wild birds (Tripathy 1991; Tripathy & Reed 2003). -

Birding Tour to Ghana Specializing on Upper Guinea Forest 12–26 January 2018

Birding Tour to Ghana Specializing on Upper Guinea Forest 12–26 January 2018 Chocolate-backed Kingfisher, Ankasa Resource Reserve (Dan Casey photo) Participants: Jim Brown (Missoula, MT) Dan Casey (Billings and Somers, MT) Steve Feiner (Portland, OR) Bob & Carolyn Jones (Billings, MT) Diane Kook (Bend, OR) Judy Meredith (Bend, OR) Leaders: Paul Mensah, Jackson Owusu, & Jeff Marks Prepared by Jeff Marks Executive Director, Montana Bird Advocacy Birding Ghana, Montana Bird Advocacy, January 2018, Page 1 Tour Summary Our trip spanned latitudes from about 5° to 9.5°N and longitudes from about 3°W to the prime meridian. Weather was characterized by high cloud cover and haze, in part from Harmattan winds that blow from the northeast and carry particulates from the Sahara Desert. Temperatures were relatively pleasant as a result, and precipitation was almost nonexistent. Everyone stayed healthy, the AC on the bus functioned perfectly, the tropical fruits (i.e., bananas, mangos, papayas, and pineapples) that Paul and Jackson obtained from roadside sellers were exquisite and perfectly ripe, the meals and lodgings were passable, and the jokes from Jeff tolerable, for the most part. We detected 380 species of birds, including some that were heard but not seen. We did especially well with kingfishers, bee-eaters, greenbuls, and sunbirds. We observed 28 species of diurnal raptors, which is not a large number for this part of the world, but everyone was happy with the wonderful looks we obtained of species such as African Harrier-Hawk, African Cuckoo-Hawk, Hooded Vulture, White-headed Vulture, Bat Hawk (pair at nest!), Long-tailed Hawk, Red-chested Goshawk, Grasshopper Buzzard, African Hobby, and Lanner Falcon. -

Avifauna of the Northern Myeik Archipelago, Taninthryi Region

Tanintharyi Conservation Programme (TCP) AVIFAUNA OF THE NORTHERN MYEIK ARCHIPELAGO, TANINTHRYI REGION REPORT ON HISTORIC AND NEW SURVEYS ALONG THE COAST OF SOUTHERN MYANMAR SAW MOSES & CHRISTOPH ZÖCKLER August 2015 TCP Report No. 18 This is a report of the FFI Myanmar “Tanintharyi Conservation Programme” With funding from: FFI Myanmar, Tanintharyi Conservation Programme The The Tanintharyi Conservation Programme is an initiative of Fauna and Flora program International (FFI) Myanmar Programme. It is implemented by FFI in collaboration with the Myanmar Forest Department and a number of local, national and international collaborators and stakeholders, notably for this survey, the Myanmar Biodiversity and Nature Conservation Association (BANCA) and ArcCona Consulting. FFI Myanmar operates the programme under two MoUs with the Forest Department and the Department of Fisheries, specifically for the achievement of shared marine and terrestrial conservation goals in Tanintharyi Region. Funding This document has been produced with the financial assistance of the European Commission, Helmsley Charitable Trust, Segre Foundation, Lighthouse Foundation and the Arcadia Fund. Suggested Saw Moses and Zöckler C., eds (2015). Avifauna of the Northern Myeik citation Archipelago, Tanintharyi: Report on Historic and New Surveys along the coast of Southern Myanmar. Report No.18 of the Tanintharyi Conservation Programme, a joint initiative of Fauna & Flora International (FFI), the Myanmar Forest Department and the Department of Fisheries. FFI, Yangon Author Saw Moses is an independent ornithologist and bird tour guide. Christoph details Zöckler (ArcCona Consulting) is an ornithologist specialising in migratory waterbirds and Asia. Both authors are advisers to FFI in Myanmar. Copyright Reproduction of this report in full or in part is granted for the purposes of education, research or awareness, with the sole provision that the authors and authoring organisations be properly credited. -

Review of the Conflict Between Migratory Birds and Electricity Power Grids in the African-Eurasian Region

CMS CONVENTION ON Distribution: General MIGRATORY UNEP/CMS/Inf.10.38/ Rev.1 SPECIES 11 November 2011 Original: English TENTH MEETING OF THE CONFERENCE OF THE PARTIES Bergen, 20-25 November 2011 Agenda Item 19 REVIEW OF THE CONFLICT BETWEEN MIGRATORY BIRDS AND ELECTRICITY POWER GRIDS IN THE AFRICAN-EURASIAN REGION (Prepared by Bureau Waardenburg for AEWA and CMS) Pursuant to the recommendation of the 37 th Meeting of the Standing Committee, the AEWA and CMS Secretariats commissioned Bureau Waardenburg to undertake a review of the conflict between migratory birds and electricity power grids in the African-Eurasian region, as well as of available mitigation measures and their effectiveness. Their report is presented in this information document and an executive summary is also provided as document UNEP/CMS/Conf.10.29. A Resolution on power lines and migratory birds is also tabled for COP as UNEP/CMS/Resolution10.11. For reasons of economy, documents are printed in a limited number, and will not be distributed at the meeting. Delegates are kindly requested to bring their copy to the meeting and not to request additional copies. The Agreement on the Conservation of African-Eurasian Migratory Waterbirds (AEWA) and the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals (CMS) REVIEW OF THE CONFLICT BETWEEN MIGRATORY BIRDS AND ELECTRICITY POWER GRIDS IN THE AFRICAN-EURASIAN REGION Funded by AEWA’s cooperation-partner, RWE RR NSG, which has developed the method for fitting bird protection markings to overhead lines by helicopter. Produced by Bureau Waardenburg Boere Conservation Consultancy STRIX Ambiente e Inovação Endangered Wildlife Trust – Wildlife & Energy Program Compiled by: Hein Prinsen 1, Gerard Boere 2, Nadine Píres 3 & Jon Smallie 4. -

Uncorrected Proof

Policy and Practice UNCORRECTED PROOF BBarney_C011.inddarney_C011.indd 117979 99/13/2008/13/2008 44:11:24:11:24 PPMM UNCORRECTED PROOF BBarney_C011.inddarney_C011.indd 118080 99/13/2008/13/2008 44:11:24:11:24 PPMM Copy edited by Richard Beatty 11 Conservation Values from Falconry Robert E. Kenward Anatrack Ltd and IUCN-SSC European Sustainable Use Specialist Group, Wareham, UK Introduction Falconry is a type of recreational hunting. This chapter considers the conser- vation issues surrounding this practice. It provides a historical background and then discusses how falconry’s role in conservation has developed and how it could grow in the future. Falconry, as defi ned by the International Association for Falconry and Conservation of Birds of Prey (IAF), is the hunting art of taking quarry in its natural state and habitat with birds of prey. Species commonly used for hunt- ing include eagles of the genera Aquila and Hieraëtus, other ‘broad-winged’ members of the Accipitrinae including the more aggressive buzzards and their relatives, ‘short-winged’ hawks of the genus Accipiter and ‘long-winged’ falcons (genus Falco). Falconers occur in more than 60 countries worldwide, mostly in North America, the Middle East, Europe, Central Asia, Japan and southern Africa. Of these countries, 48 are members of the IAF. In the European Union falconry Recreational Hunting, Conservation and Rural Livelihoods: Science and Practice, 1st edition. Edited by B. Dickson, J. Hutton and B. Adams. © 2009 Blackwell Publishing, UNCORRECTEDISBN 978-1-4051-6785-7 (pb) and 978-1-4051-9142-5 (hb). PROOF BBarney_C011.inddarney_C011.indd 118181 99/13/2008/13/2008 44:11:24:11:24 PPMM Copy edited by Richard Beatty 182 ROBERT E. -

Avian Taxonomy

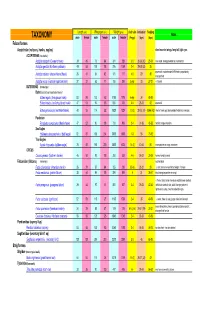

Length (cm) Wing span (cm) Weight (gms) cluch size incubation fledging Notes TAXONOMY male female male female male female (# eggs) (days) (days) Falconiformes Accipitridae (vultures, hawks, eagles) short rounded wings; long tail; light eyes ACCIPITRINAE (true hawks) Accipiter cooperii (Cooper's hawk) 39 45 73 84 341 528 3-5 30-36 (30) 25-34 crow sized; strongly banded tail; rounded tail Accipiter gentilis (Northern goshawk) 49 58 101 108 816 1059 2-4 28-38 (33) 35 square tail; most abundant NAM hawk; proportionaly 26 31 54 62 101 177 4-5 29 30 Accipiter striatus (sharp-shinned hawk) strongest foot Accipiter nisus (Eurasian sparrowhawk ) 37 37 62 77 150 290 5-Apr 33 27-31 Musket BUTEONINAE (broadwings) Buteo (buzzards or broad tailed hawks) Buteo regalis (ferruginous hawk) 53 59 132 143 1180 1578 6-Apr 34 45-50 Buteo lineatus (red-shouldered hawk) 47 53 96 105 550 700 3-4 28-33 42 square tail Buteo jamaicensis (red-tailed hawk) 48 55 114 122 1028 1224 1-3 (3) 28-35 (34) 42-46 (42) (Harlan' hawk spp); dark patagial featehres: immature; Parabuteo Parabuteo cuncincutus (Harris hawk) 47 52 90 108 710 890 2-4 31-36 45-50 reddish orange shoulders Sea Eagles Haliaeetus leucocephalus (bald eagle) 82 87 185 244 3000 6300 1-3 35 70-92 True Eagles Aquila chrysaetos (golden eagle) 78 82 185 220 3000 6125 1-4 (2) 40-45 50 white patches on wings: immature; CIRCUS Circus cyaneus (Northern harrier) 46 50 93 108 350 530 4-6 26-32 30-35 hovers; hunts by sound Falconidae (falcons) (longwings) notched beak Falco columbarius (American merlin) 26 29 57 64 -

Download This PDF File

#86 Bird-o-soar 21 May 2021 Rediscovery of Crested Goshawk from southern Bengal, India Crested Goshawk Accipiter trivirgatus (Temminck, 1824) is a small-sized bird of prey belonging to the family Accipitridae. It is considered as Least Concern as per IUCN assessment in 2016 (BirdLife International 2016). This bird species is resident and can be found mainly in the Himalaya, northeastern portion and southwestern region of the Indian subcontinent where it prefers mostly the dense, deciduous, evergreen tropical, and subtropical forests Image 1. Crested Goshawk from Biharinath Hills, Bankura. © (Grimmett et al. 2011). The Debayan Gayen on 27 February 2021. population of this species is supposed to be declining spp., Bauhinia spp., and their alternative black and white tail due to the anthropogenic associated species. This bands of equal width, (v) white interventions and habitat forest is mainly used as a under tail covert, (vi) heavily destructions (BirdLife tourist destination and also dark brown streaked breast, International 2016). villagers collect firewood from and (vii) bold dark brown- here. The bird was seen flying barred belly (Naoroji 2006; An adult individual was first above the canopy layer and Clark & Marks 2020). Besra observed on 27 February photographs were taken. Accipiter virgatus shows 2021 at Biharinath Hill, Bankura (23.57640N, 86.95330 similar pattern to undertail E) (Adhurya et al. 2021). The bird was identified covert, mesial stripe and tail The habitat was typically a based on the following banding. But it shows five tropical deciduous forest characteristics: (i) six primary fingers instead of six as in with mainly tree species like fingers in flight, (ii) bright Crested Goshawk and also Shorea robusta, Madhuca yellow iris, (iii) white throat slimmer in appearance (Chow sp., Terminalis spp., Acacia with black mesial stripe, (iv) 2011). -

Over-Ocean Raptor Migration in a Monsoon Regime: Spring and Autumn 2007 on Sangihe, North Sulawesi, Indonesia

FO@9TA"+ -0 %-00(35 '0*E''> Over-ocean raptor migration in a monsoon regime: spring and autumn 2007 on Sangihe North Su!a"esi Indonesia FRANCESCO $ERMI, GEORGE !2 ?OUNG, AGUS SALIM, WESLEY ,ANGIMANGEN and MARK SCHELLEKENS Buring spring and autumn -00) we carried out full season raptor migration counts on !angihe "sland, "ndonesia2 "n autumn, -;0,-'* migratory raptors were recorded2 Chinese !parrowhaw6 Accipiter soloensis comprised appro8imately (8C of the flight2 The count results indicate that the largest movements of this species towards the wintering grounds of eastern "ndonesia occur along the East Asian Oceanic Flyway, and not the Continental Flyway as previously thought2 /oth spring and autumn migrations occurred in the face of monsoon headwinds2 The relationship between migrant counts and day to day variation in wind direction in !angihe differed between the two seasons2 &ore migrants were counted during crosswind conditions in spring when their route ta6es them along closely spaced islands than during similar conditions in autumn, when they run the ris6 of being blown off course during longer over water legs2 Bisplacement over the sea by crosswinds coupled with records from other islands point to the e8istence of an additional and heretofore un6nown eastern route, involving longer water crossings, between &indanao and the northern &oluccas via the Talaud "slands2 <e gathered evidence that Chinese !parrowhaw6 behave nomadically during the non breeding season, following local food abundances of seasonal insect outbrea6s induced -

Crow Threat to Raptors?

PIED pirates CROW THREAT TO RAPTORS? There has been much debate about the effects on biodiversity of increasing Pied Crow and other corvid populations in Africa, but little has been quantified. It is evident from the latest bird atlas data that there are now more Pied Crows in southern Africa than there were a decade ago and that the species has spread into areas of the Karoo where it did not occur previously. But what effect is this having on other bird species? TEXT BY ROB SIMMONS & PHOEBE BARNARD ALBERT FRONEMAN arious reports indicate that one a Rock Kestrel and another a Southern crows are impacting negatively Pale Chanting Goshawk, all of which were on other creatures in their en- carrying mice in their talons. Prey-carrying vironment. Farmers complain raptors are usually provisioning dependent aboutV increasing predation by ‘crows’ on females or nestlings, so piracy affects more lambing ewes, birders suggest that more at- than simply the bird with the food. tacks are occurring on passerine birds, and The following three incidents serve to conservationists and members of the pub- highlight the modus operandi of the crows. lic report greater numbers of crows killing We then investigated other parts of Africa small tortoises. However, almost nothing to determine if piracy targeting raptors is has been quantified as to the level of such limited to western South Africa as a zone predation, the magnitude of the upsurge of Pied Crow range expansion or is a more in crow interactions and the effect on the widespread strategy. species being attacked. We do not yet have In the West Coast National Park in such data, but we do take a first look at 2008, our attention was drawn to a Black- what may be an increasing and somewhat shouldered Kite that was calling from a surprising addition to the negative effects height of over 150 metres and circling up- of crows – those on birds of prey. -

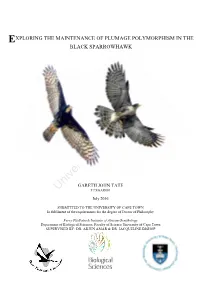

Exploring the Maintenance of Plumage Polymorphism in the Black Sparrowhawk

EXPLORING THE MAINTENANCE OF PLUMAGE POLYMORPHISM IN THE BLACK SPARROWHAWK GARETH JOHN TATE UniversityTTXGAR001 of Cape Town July 2016 SUBMITTED TO THE UNIVERSITY OF CAPE TOWN In fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Percy FitzPatrick Institute of African Ornithology Department of Biological Sciences, Faculty of Science University of Cape Town SUPERVISED BY: DR. ARJUN AMAR & DR. JACQUELINE BISHOP The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgement of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Published by the University of Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. University of Cape Town CONTENTS ABSTRACT------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 4 CHAPTER 1: Introduction--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 8 CHAPTER 2: Trait divergence in the presence of gene flow? A mitochondrial perspective on trait variation and colonisation of the Cape Peninsula by the black sparrowhawk Accipiter