Goshawk (Accipiter Gentilis): Species Assessment - Draft

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gyrfalcon Falco Rusticolus

Gyrfalcon Falco rusticolus Rob Florkiewicz surveys, this area was included. Eight eyries are known from this Characteristics and Range The northern-dwelling Gyrfalcon is part of the province; however, while up to 7 of these eyries have the largest falcon in the world. It breeds mostly along the Arctic been deemed occupied in a single year, no more than 3 have been coasts of North America, Europe and Asia (Booms et al. 2008). productive at the same time. Based on these data and other Over its range, its colour varies from white through silver-grey to sightings, the British Columbia Wildlife Branch estimates the almost black; silver-grey is the most common morph in British breeding population in the province to be fewer than 20 pairs Columbia. It nests on cliff ledges at sites that are often used for (Chutter 2008). decades and where considerable amounts of guano can accumulate. Ptarmigan provide the Gyrfalcon's main prey in In British Columbia, the Gyrfalcon nests on cliff ledges on British Columbia and productivity appears dependent on mountains in alpine areas, usually adjacent to rivers or lakes. ptarmigan numbers. Large size and hunting prowess make the Occasionally, it nests on cliffs of river banks and in abandoned Gyrfalcon a popular bird with falconers, who breed and train Golden Eagle nests. them to hunt waterfowl and other game birds. Conservation and Recommendations Whilst the Gyrfalcon is Distribution, Abundance, and Habitat Most Gyrfalcons breed designated as Not at Risk nationally by COSEWIC, it is Blue-listed along the Arctic coast; however, a few breed in the northwest in British Columbia due to its small known breeding population portion of the Northern Boreal Mountains Ecoprovince of British (British Columbia Ministry of Environment 2014). -

THE LONG-EARED OWL INSIDE by CHRIS NERI and NOVA MACKENTLEY News from the Board and Staff

WINTER 2014 TAKING FLIGHT NEWSLETTER OF HAWK RIDGE BIRD OBSERVATORY The elusive Long-eared Owl Photo by Chris Neri THE LONG-EARED OWL INSIDE by CHRIS NERI and NOVA MACKENTLEY News from the Board and Staff..... 2 For many birders thoughts of Long-eared Owls invoke memories of winter Education Updates .................. 4 visits to pine stands in search of this often elusive species. It really is magical Research Features................... 6 to enter a pine stand, find whitewash and pellets at the base of trees and realize that Long-eareds are using the area that you are searching. You scan Stewardship Notes ................. 12 up the trees examining any dark spot, usually finding it’s just a tangle of Volunteer Voices.................... 13 branches or a cluster of pine needles, until suddenly your gaze is met by a Hawk Ridge Membership........... 14 pair of yellow eyes staring back at you from a body cryptically colored and Snore Outdoors for HRBO ......... 15 stretched long and thin. This is often a birders first experience with Long- eared Owls. However, if you are one of those that have journeyed to Hawk Ridge at night for one of their evening owl programs, perhaps you were fortunate enough to see one of these beautiful owls up close. CONTINUED ON PAGE 3 HAWK RIDGE BIRD OBSERVATORY 1 NOTES FROM THE DIRECTOR BOARD OF DIRECTORS by JANELLE LONG, EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR As I look back to all of the accomplishments of this organization, I can’t help but feel proud CHAIR for Hawk Ridge Bird Observatory and to be a part of it. -

Patterns of Co-Occurrence in Woodpeckers and Nocturnal Cavity-Nesting Owls Within an Idaho Forest

VOLUME 13, ISSUE 1, ARTICLE 18 Scholer, M. N., M. Leu, and J. R. Belthoff. 2018. Patterns of co-occurrence in woodpeckers and nocturnal cavity-nesting owls within an Idaho forest. Avian Conservation and Ecology 13(1):18. https://doi.org/10.5751/ACE-01209-130118 Copyright © 2018 by the author(s). Published here under license by the Resilience Alliance. Research Paper Patterns of co-occurrence in woodpeckers and nocturnal cavity- nesting owls within an Idaho forest Micah N. Scholer 1, Matthias Leu 2 and James R. Belthoff 1 1Department of Biological Sciences and Raptor Research Center, Boise State University, Boise, Idaho, USA, 2Biology Department, College of William and Mary, Williamsburg, Virginia, USA ABSTRACT. Few studies have examined the patterns of co-occurrence between diurnal birds such as woodpeckers and nocturnal birds such as owls, which they may facilitate. Flammulated Owls (Psiloscops flammeolus) and Northern Saw-whet Owls (Aegolius acadicus) are nocturnal, secondary cavity-nesting birds that inhabit forests. For nesting and roosting, both species require natural cavities or, more commonly, those that woodpeckers create. Using day and nighttime broadcast surveys (n = 150 locations) in the Rocky Mountain biogeographic region of Idaho, USA, we surveyed for owls and woodpeckers to assess patterns of co-occurrence and evaluated the hypothesis that forest owls and woodpeckers co-occurred more frequently than expected by chance because of the facilitative nature of their biological interaction. We also examined co-occurrence patterns between owl species to understand their possible competitive interactions. Finally, to assess whether co-occurrence patterns arose because of species interactions or selection of similar habitat types, we used canonical correspondence analysis (CCA) to examine habitat associations within this cavity-nesting bird community. -

Wildlife of the North Hills: Birds, Animals, Butterflies

Wildlife of the North Hills: Birds, Animals, Butterflies Oakland, California 2005 About this Booklet The idea for this booklet grew out of a suggestion from Anne Seasons, President of the North Hills Phoenix Association, that I compile pictures of local birds in a form that could be made available to residents of the north hills. I expanded on that idea to include other local wildlife. For purposes of this booklet, the “North Hills” is defined as that area on the Berkeley/Oakland border bounded by Claremont Avenue on the north, Tunnel Road on the south, Grizzly Peak Blvd. on the east, and Domingo Avenue on the west. The species shown here are observed, heard or tracked with some regularity in this area. The lists are not a complete record of species found: more than 50 additional bird species have been observed here, smaller rodents were included without visual verification, and the compiler lacks the training to identify reptiles, bats or additional butterflies. We would like to include additional species: advice from local experts is welcome and will speed the process. A few of the species listed fall into the category of pests; but most - whether resident or visitor - are desirable additions to the neighborhood. We hope you will enjoy using this booklet to identify the wildlife you see around you. Kay Loughman November 2005 2 Contents Birds Turkey Vulture Bewick’s Wren Red-tailed Hawk Wrentit American Kestrel Ruby-crowned Kinglet California Quail American Robin Mourning Dove Hermit thrush Rock Pigeon Northern Mockingbird Band-tailed -

American Robin

American Robin DuPage Birding Club, 2020 American Robin Appearance A chunky, heavy-bodied bird with a relatively small dark head. Sexually dimorphic, meaning the male and female look different. American Robins are a uniform dark gray with a brick red breast. Female Male Females are a lighter gray with a lighter breast. Males tend to be darker with a brighter red breast. Males are larger than females. Photos: Elmarie Von Rooyen (left), Jackie Tilles (right) DuPage Birding Club, 2020 2 American Robin Appearance American Robins are a medium-size bird with a length of about ten inches. They are so common that they are a good bird to compare size with when you come across an unknown bird. Is the bird bigger than an American Robin or smaller than an American Robin? Judging the size of a bird is very helpful in identifying an unknown bird. Chart: The Cornell Lab, All About Birds https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/American_Robin/id DuPage Birding Club, 2020 3 American Robin Appearance Juvenile American Robins have a speckled breast with a tint of rusty red. Photos: Natalie McFaul DuPage Birding Club, 2020 4 American Robin Sounds From The Cornell Lab of Ornithology: https://www.birds.cornell.edu/home/ SONGS The musical song of the American Robin is a familiar sound of spring. It’s a string of 10 or so clear whistles assembled from a few often- repeated syllables, and often described as cheerily, cheer up, cheer up, cheerily, cheer up. The syllables rise and fall in pitch but are delivered at a steady rhythm, with a pause before the bird begins singing again. -

Accipiters.Pdf

Accipiters The northern goshawk (Accipiter gentilis) and the sharp-shinned hawk (Accipiter striatus) are the Alaskan representatives of a group of hawks known as accipiters, with short, rounded wings (short in comparison with other hawks) and long tails. The third North American accipiter, the Cooper’s hawk (Accipiter cooperii) is not found in Alaska. Both native species are abundant in the state but not commonly seen, for they spend the majority of their time in wooded habitats. When they do venture out into the open, the accipiters can be recognized easily by their “several flaps and a glide” style of flight. General Description: Adult northern goshawks are bluish- gray on the back, wings, and tail, and pearly gray on the breast and underparts. The dark gray cap is accented by a light gray stripe above the red eye. Like most birds of prey, female goshawks are larger than males. A typical female is 25 inches (65 cm) long, has a wingspread of 45 inches (115 cm) and weighs 2¼ pounds (1020 g) while the average male is 19½ inches (50 cm) in length with a wingspread of 39 inches (100 cm) and weighs 2 pounds (880 g). Adult sharp-shinned hawks have gray backs, wings and tails (males tend to be bluish-gray, while females are browner) with white underparts barred heavily with brownish-orange. They also have red eyes but, unlike goshawks, have no eyestrip. A typical female weighs 6 ounces (170 g), is 13½ inches (35 cm) long with a wingspread of 25 inches (65 cm), while the average male weighs 3½ ounces (100 g), is 10 inches (25 cm) long and has a wingspread of 21 inches (55 cm). -

Our Recent Bird Surveys

Breeding Birds Survey at Germantown MetroPark Scientific Name Common Name Scientific Name Common Name Accipiter cooperii hawk, Cooper's Corvus brachyrhynchos crow, American Accipiter striatus hawk, sharp shinned Cyanocitta cristata jay, blue Aegolius acadicus owl, saw-whet Dendroica cerulea warbler, cerulean Agelaius phoeniceus blackbird, red-winged Dendroica coronata warbler, yellow-rumped Aix sponsa duck, wood Dendroica discolor warbler, prairie Ammodramus henslowii sparrow, Henslow's Dendroica dominica warbler, yellow-throated Ammodramus savannarum sparrow, grasshopper Dendroica petechia warbler, yellow Anas acuta pintail, northern Dendroica pinus warbler, pine Anas crecca teal, green-winged Dendroica virens warbler, black-throated Anas platyrhynchos duck, mallard green Archilochus colubris hummingbird, ruby-throated Dolichonyx oryzivorus Bobolink Ardea herodias heron, great blue Dryocopus pileatus woodpecker, pileated Asio flammeus owl, short-eared Dumetella carolinensis catbird, grey Asio otus owl, long-eared Empidonax minimus flycatcher, least Aythya collaris duck, ring-necked Empidonax traillii flycatcher, willow Baeolphus bicolor titmouse, tufted Empidonax virescens flycatcher, Acadian Bombycilla garrulus waxwing, cedar Eremophia alpestris lark, horned Branta canadensis goose, Canada Falco sparverius kestrel, American Bubo virginianus owl, great horned Geothlypis trichas yellowthroat, common Buteo jamaicensis hawk, red-tailed Grus canadensis crane, sandhill Buteo lineatus hawk, red-shouldered Helmitheros vermivorus warbler, worm-eating -

Revised January 19, 2018 Updated June 19, 2018

BIOLOGICAL EVALUATION / BIOLOGICAL ASSESSMENT FOR TERRESTRIAL AND AQUATIC WILDLIFE YUBA PROJECT YUBA RIVER RANGER DISTRICT TAHOE NATIONAL FOREST REVISED JANUARY 19, 2018 UPDATED JUNE 19, 2018 PREPARED BY: MARILYN TIERNEY DISTRICT WILDLIFE BIOLOGIST 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................................... 3 II. INTRODUCTION.......................................................................................................................... 4 III. CONSULTATION TO DATE ...................................................................................................... 4 IV. CURRENT MANAGEMENT DIRECTION ............................................................................... 5 V. DESCRIPTION OF THE PROPOSED PROJECT AND ALTERNATIVES ......................... 6 VI. EXISTING ENVIRONMENT, EFFECTS OF THE PROPOSED ACTION AND ALTERNATIVES, AND DETERMINATION ......................................................................... 41 SPECIES-SPECIFIC ANALYSIS AND DETERMINATION ........................................................... 54 TERRESTRIAL SPECIES ........................................................................................................................ 55 WESTERN BUMBLE BEE ............................................................................................................. 55 BALD EAGLE ............................................................................................................................... -

Immature Northern Goshawk Captures, Kills, and Feeds on Adult&Hyphen

DECEMUER2003 SHO•tT COMMUNICATIONS 337 [EDs.], Proceedingsof the 4th Workshop of Bearded Vulture (Gypaetusbarbatus) in the Pyrenees:influence Vulture. Natural History Museum of Crete and Uni- on breeding success.Bird Study46:224-229. versity of Crete, Iraklio, Greece. --AND --. 2002. Pla de recuperaci6 del trenca- --AND M. RAZIN.1999. Ecologyand conservationof 16s a Catalunya: biologia i conservaci6. Documents the Bearded Vultures: the case of the Spanish and dels Quaderns de Medi Ambient, 7. Generalitat de French Pyrenees.Pages 29-45 in M. Mylonas [ED.], Catalunya, Departament de Medi Ambient, Barcelo- Proceedingsof the Bearded Vulture Workshop. Nat- na, Spain. ural History Museum of Crete and University of , ---,J. BERTP,AN, ANt) R. HERrre^. 2003. Breed- Crete, Iraklio, Greece. ing biology and successof the Bearded Vulture HIRALDO,F., M. DELIBES,ANDJ. CALDER(SN. 1979. E1 Que- (Gypaetusbarbatus) in the eastern Pyrenees.Ibis 145 brantahuesos(Gypaetus barbatus). L. Monografias 22. 244-252. ICONA, Madrid, Spain. , --, AND R. HE•Em^. 1997. Estimaci6n de la MARGAiJDA,A. ANDJ. BERTRAN.2000a. Nest-buildingbe- disponibilidad tr6fica para el Quebrantahuesosen Ca- haviour of the Bearded Vulture (Gypaetusbarbatus). talufia (NE Espafia) e implicacionessobre su conser- Ardea 88:259-264. vaci6n. Do•ana, Acta Vertetm24:227-235. --AND --. 2000b. Breeding behaviour of the NEWTON,I. 1979. Populationecology ofraptors. T. &A D Bearded Vulture (Gypaetusbarbatus): minimal sexual Poyser,Berkhamsted, UK. differencesin parental activities.Ibis 142:225-234. ß 1986. The Sparrowhawk.T. & A.D. Poyser,Cal- --AND --. 2001. Function and temporal varia- ton, UK. tion in the use of ossuaries by Bearded Vultures --^NO M. MA•QUtSS.1982. Fidelity to breeding area (Gypaetusbarbatus) during the nestling period. -

Uncorrected Proof

Policy and Practice UNCORRECTED PROOF BBarney_C011.inddarney_C011.indd 117979 99/13/2008/13/2008 44:11:24:11:24 PPMM UNCORRECTED PROOF BBarney_C011.inddarney_C011.indd 118080 99/13/2008/13/2008 44:11:24:11:24 PPMM Copy edited by Richard Beatty 11 Conservation Values from Falconry Robert E. Kenward Anatrack Ltd and IUCN-SSC European Sustainable Use Specialist Group, Wareham, UK Introduction Falconry is a type of recreational hunting. This chapter considers the conser- vation issues surrounding this practice. It provides a historical background and then discusses how falconry’s role in conservation has developed and how it could grow in the future. Falconry, as defi ned by the International Association for Falconry and Conservation of Birds of Prey (IAF), is the hunting art of taking quarry in its natural state and habitat with birds of prey. Species commonly used for hunt- ing include eagles of the genera Aquila and Hieraëtus, other ‘broad-winged’ members of the Accipitrinae including the more aggressive buzzards and their relatives, ‘short-winged’ hawks of the genus Accipiter and ‘long-winged’ falcons (genus Falco). Falconers occur in more than 60 countries worldwide, mostly in North America, the Middle East, Europe, Central Asia, Japan and southern Africa. Of these countries, 48 are members of the IAF. In the European Union falconry Recreational Hunting, Conservation and Rural Livelihoods: Science and Practice, 1st edition. Edited by B. Dickson, J. Hutton and B. Adams. © 2009 Blackwell Publishing, UNCORRECTEDISBN 978-1-4051-6785-7 (pb) and 978-1-4051-9142-5 (hb). PROOF BBarney_C011.inddarney_C011.indd 118181 99/13/2008/13/2008 44:11:24:11:24 PPMM Copy edited by Richard Beatty 182 ROBERT E. -

Avian Taxonomy

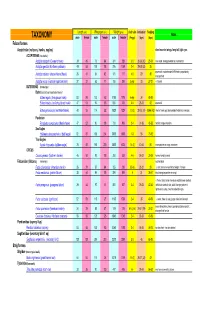

Length (cm) Wing span (cm) Weight (gms) cluch size incubation fledging Notes TAXONOMY male female male female male female (# eggs) (days) (days) Falconiformes Accipitridae (vultures, hawks, eagles) short rounded wings; long tail; light eyes ACCIPITRINAE (true hawks) Accipiter cooperii (Cooper's hawk) 39 45 73 84 341 528 3-5 30-36 (30) 25-34 crow sized; strongly banded tail; rounded tail Accipiter gentilis (Northern goshawk) 49 58 101 108 816 1059 2-4 28-38 (33) 35 square tail; most abundant NAM hawk; proportionaly 26 31 54 62 101 177 4-5 29 30 Accipiter striatus (sharp-shinned hawk) strongest foot Accipiter nisus (Eurasian sparrowhawk ) 37 37 62 77 150 290 5-Apr 33 27-31 Musket BUTEONINAE (broadwings) Buteo (buzzards or broad tailed hawks) Buteo regalis (ferruginous hawk) 53 59 132 143 1180 1578 6-Apr 34 45-50 Buteo lineatus (red-shouldered hawk) 47 53 96 105 550 700 3-4 28-33 42 square tail Buteo jamaicensis (red-tailed hawk) 48 55 114 122 1028 1224 1-3 (3) 28-35 (34) 42-46 (42) (Harlan' hawk spp); dark patagial featehres: immature; Parabuteo Parabuteo cuncincutus (Harris hawk) 47 52 90 108 710 890 2-4 31-36 45-50 reddish orange shoulders Sea Eagles Haliaeetus leucocephalus (bald eagle) 82 87 185 244 3000 6300 1-3 35 70-92 True Eagles Aquila chrysaetos (golden eagle) 78 82 185 220 3000 6125 1-4 (2) 40-45 50 white patches on wings: immature; CIRCUS Circus cyaneus (Northern harrier) 46 50 93 108 350 530 4-6 26-32 30-35 hovers; hunts by sound Falconidae (falcons) (longwings) notched beak Falco columbarius (American merlin) 26 29 57 64 -

Identifying a Bird Species from the Temple of Hatshepsut at Deir El-Bahari

The secretarybird dilemma: identifying a bird species from the Temple of Hatshepsut at Deir el-Bahari Abstract: Known from a few representations in Predynastic Egyp- tian art, the secretarybird has otherwise been elusive, in the art of Pharaonic Egypt as well as the scientific discourse on icono- graphic imagery of birds in ancient Egypt. The author’s studies of the animal decoration at the Temple for her doctoral dissertation identified three images of birds belonging most likely to the same species, depicted in the context of the expedition of Hatshepsut shown in the Portico of Punt. The zoological identification of the species as the secretarybird (another possibility is the African harrier-hawk) derives from an in-depth analysis of the bird’s sys- tematics, appearance, distribution and habitat, as well as behavior, which are essential for proper species recognition and instrumen- tal for understanding the rationale behind bringing this particular bird from the “God’s Land”. Iconographic features contesting this identification and suggesting a different species, that is, the African harrier-hawk, are discussed based on a combination of theoretical background, material analysis, on-site interviews with experts and the author’s personal experience with the species. Keywords: African animals, birds in Ancient Egypt, secretarybird, African harrier-hawk, temple of Hatshepsut, Deir el-Bahari, Hat- shepsut Punt expedition, temple decoration A bird depicted in possibly three separate scenes from the Southern Middle Portico of the Temple of Hat- shepsut in Deir el-Bahari, documented in 2012 by the author as part of her extended study of animals in the decoration of this Eighteenth Dynasty sanctuary [Fig.