A Partial Post-Juvenile Molt and Transitional Plumage in the Shikra (Accipiter Badius) and Grey Frog Hawk ( a Ccipiter Soloensis)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Birds (Aves) of Oromia, Ethiopia – an Annotated Checklist

European Journal of Taxonomy 306: 1–69 ISSN 2118-9773 https://doi.org/10.5852/ejt.2017.306 www.europeanjournaloftaxonomy.eu 2017 · Gedeon K. et al. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License. Monograph urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:A32EAE51-9051-458A-81DD-8EA921901CDC The birds (Aves) of Oromia, Ethiopia – an annotated checklist Kai GEDEON 1,*, Chemere ZEWDIE 2 & Till TÖPFER 3 1 Saxon Ornithologists’ Society, P.O. Box 1129, 09331 Hohenstein-Ernstthal, Germany. 2 Oromia Forest and Wildlife Enterprise, P.O. Box 1075, Debre Zeit, Ethiopia. 3 Zoological Research Museum Alexander Koenig, Centre for Taxonomy and Evolutionary Research, Adenauerallee 160, 53113 Bonn, Germany. * Corresponding author: [email protected] 2 Email: [email protected] 3 Email: [email protected] 1 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:F46B3F50-41E2-4629-9951-778F69A5BBA2 2 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:F59FEDB3-627A-4D52-A6CB-4F26846C0FC5 3 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:A87BE9B4-8FC6-4E11-8DB4-BDBB3CFBBEAA Abstract. Oromia is the largest National Regional State of Ethiopia. Here we present the first comprehensive checklist of its birds. A total of 804 bird species has been recorded, 601 of them confirmed (443) or assumed (158) to be breeding birds. At least 561 are all-year residents (and 31 more potentially so), at least 73 are Afrotropical migrants and visitors (and 44 more potentially so), and 184 are Palaearctic migrants and visitors (and eight more potentially so). Three species are endemic to Oromia, 18 to Ethiopia and 43 to the Horn of Africa. 170 Oromia bird species are biome restricted: 57 to the Afrotropical Highlands biome, 95 to the Somali-Masai biome, and 18 to the Sudan-Guinea Savanna biome. -

Reproduction and Behaviour of the Long-Legged Buzzard (.Buteo Rufinus) in North-Eastern Greece

© Deutschen Ornithologen-Gesellschaft und Partner; download www.do-g.de; www.zobodat.at Die Vogelwarte 39, 1998: 176-182 Reproduction and behaviour of the Long-legged Buzzard (.Buteo rufinus) in North-eastern Greece By Haralambos Alivizatos, Vassilis Goutner and Michael G. Karandinos Abstract: Alivizatos , H., V. Goutner & M. G. Karandinos (1998): Reproduction and behaviour of the Long- legged Buzzard ( Buteo rufinus) in North-eastern Greece. Vogelwarte 39: 176-182. The breeding biology of the Long-legged Buzzard ( Buteo rufinus) was studied in the Evros area, north-eastern Greece in 1989, 1990, 1992 and 1993. The mean number of young fledged per pair per year was similar between years with an overall average of 0.93 (1.58 per successful pair). Of ten home range variables examined, the num ber of alternative nest sites and the extent of forest free areas in home ranges were significant predictors of nest ling productivity. Aggressive interactions were observed with 18 bird species (of which 12 were raptors), most commonly with the Buzzard {Buteo buteo). Such interactions declined during the course of the season. Prey pro visioning to nestlings was greatest in the morning and late in the afternoon declining in the intermediate period. Key words: Buteo rufinus, reproduction, behaviour, Greece. Addresses: Zaliki 4, GR-115 24 Athens, Greece (H. A.); Department of Zoology, Aristotelian University of Thessaloniki, GR-54006, Thessaloniki, Macedonia, Greece (V. G.); Laboratory of Ecology and Environmental Sciences, Agricultural University of Athens 75 Iera Odos 1 1855 Athens, Greece (M. G. K.). 1. Introduction The Long-legged Buzzard (Buteo rufinus) is a little known raptor of Europe. -

Accipiters.Pdf

Accipiters The northern goshawk (Accipiter gentilis) and the sharp-shinned hawk (Accipiter striatus) are the Alaskan representatives of a group of hawks known as accipiters, with short, rounded wings (short in comparison with other hawks) and long tails. The third North American accipiter, the Cooper’s hawk (Accipiter cooperii) is not found in Alaska. Both native species are abundant in the state but not commonly seen, for they spend the majority of their time in wooded habitats. When they do venture out into the open, the accipiters can be recognized easily by their “several flaps and a glide” style of flight. General Description: Adult northern goshawks are bluish- gray on the back, wings, and tail, and pearly gray on the breast and underparts. The dark gray cap is accented by a light gray stripe above the red eye. Like most birds of prey, female goshawks are larger than males. A typical female is 25 inches (65 cm) long, has a wingspread of 45 inches (115 cm) and weighs 2¼ pounds (1020 g) while the average male is 19½ inches (50 cm) in length with a wingspread of 39 inches (100 cm) and weighs 2 pounds (880 g). Adult sharp-shinned hawks have gray backs, wings and tails (males tend to be bluish-gray, while females are browner) with white underparts barred heavily with brownish-orange. They also have red eyes but, unlike goshawks, have no eyestrip. A typical female weighs 6 ounces (170 g), is 13½ inches (35 cm) long with a wingspread of 25 inches (65 cm), while the average male weighs 3½ ounces (100 g), is 10 inches (25 cm) long and has a wingspread of 21 inches (55 cm). -

Our Recent Bird Surveys

Breeding Birds Survey at Germantown MetroPark Scientific Name Common Name Scientific Name Common Name Accipiter cooperii hawk, Cooper's Corvus brachyrhynchos crow, American Accipiter striatus hawk, sharp shinned Cyanocitta cristata jay, blue Aegolius acadicus owl, saw-whet Dendroica cerulea warbler, cerulean Agelaius phoeniceus blackbird, red-winged Dendroica coronata warbler, yellow-rumped Aix sponsa duck, wood Dendroica discolor warbler, prairie Ammodramus henslowii sparrow, Henslow's Dendroica dominica warbler, yellow-throated Ammodramus savannarum sparrow, grasshopper Dendroica petechia warbler, yellow Anas acuta pintail, northern Dendroica pinus warbler, pine Anas crecca teal, green-winged Dendroica virens warbler, black-throated Anas platyrhynchos duck, mallard green Archilochus colubris hummingbird, ruby-throated Dolichonyx oryzivorus Bobolink Ardea herodias heron, great blue Dryocopus pileatus woodpecker, pileated Asio flammeus owl, short-eared Dumetella carolinensis catbird, grey Asio otus owl, long-eared Empidonax minimus flycatcher, least Aythya collaris duck, ring-necked Empidonax traillii flycatcher, willow Baeolphus bicolor titmouse, tufted Empidonax virescens flycatcher, Acadian Bombycilla garrulus waxwing, cedar Eremophia alpestris lark, horned Branta canadensis goose, Canada Falco sparverius kestrel, American Bubo virginianus owl, great horned Geothlypis trichas yellowthroat, common Buteo jamaicensis hawk, red-tailed Grus canadensis crane, sandhill Buteo lineatus hawk, red-shouldered Helmitheros vermivorus warbler, worm-eating -

Iucn Red Data List Information on Species Listed On, and Covered by Cms Appendices

UNEP/CMS/ScC-SC4/Doc.8/Rev.1/Annex 1 ANNEX 1 IUCN RED DATA LIST INFORMATION ON SPECIES LISTED ON, AND COVERED BY CMS APPENDICES Content General Information ................................................................................................................................................................................................................................ 2 Species in Appendix I ............................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 3 Mammalia ............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................ 4 Aves ...................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 7 Reptilia ............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 12 Pisces ................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................. -

A New Female-Like Morph of Juvenile Male Levant Sparrowhawk (Accipiter Brevipes) – Sexual Mimicry to Avoid Intra-Specific Predation?

EUROPEAN JOURNALEUROPEAN OF ECOLOGY JOURNAL OF ECOLOGY EJE 2015, 1(1): 64-67, doi: 10.1515/eje-2015-0008 A new female-like morph of juvenile male Levant Sparrowhawk (Accipiter brevipes) – sexual mimicry to avoid intra-specific predation? Reuven Yosef1, Lorenzo Fornasari2 1 Ben Gurion University ABSTRACT - Eilat Campus, P. O. Box In migrant Levant Sparrowhawk (Accipiter brevipes) at Eilat, Israel, we noted that juvenile males had two differ- 272, Eilat 88000, Israel ent morphs – the one described to date in literature; and a second, previously undescribed morph, with female- Corresponding Author: [email protected] like barring on the chest and flanks interspersed with tear-shaped elongated spots, giving an overall female-like appearance. Here we forward the hypothesis that explain the evolutionary consequences for the female-like 2 FaunaViva - Viale Sar- plumage of juvenile males as that of intra-specific sex mimicry developed to avoid intra-specific predation by ca, 78 - 20125 Milano, the larger females. Italy, e-mail: lorenzo. [email protected] KEYWORDS Levant sparrowhawk – intraspecific predation – avoidance – morph © 2015 Reuven Yosef, Lorenzo Fornasari This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs license INTRODUCTION The Levant Sparrowhawk has dichromatism and re- Chromatic mimicry as a strategy to avoid inter-specific preda- versed sexual size dimorphism wherein the female is larger by tion, or to have a reproductive advantage, is well documented 9–10% than the male (Cramp & Simmons 1980; Clark & Yosef in many insect, amphibian and reptilian taxa (e.g.Gross & Char- 1997). The sexes also differ in colour, and the male has blue- nov 1980; Krebs & Davies 1987). -

A New Female-Like Morph of Juvenile Male Levant Sparrowhawk (Accipiter Brevipes) – Sexual Mimicry to Avoid Intra-Specific Predation?

EUROPEAN JOURNALEUROPEAN OF ECOLOGY JOURNAL OF ECOLOGY EJE 2015, 1(1): 64-67, doi: 10.1515/eje-2015-0008 A new female-like morph of juvenile male Levant Sparrowhawk (Accipiter brevipes) – sexual mimicry to avoid intra-specific predation? Reuven Yosef1, Lorenzo Fornasari2 1 Ben Gurion University ABSTRACT - Eilat Campus, P. O. Box In migrant Levant Sparrowhawk (Accipiter brevipes) at Eilat, Israel, we noted that juvenile males had two differ- 272, Eilat 88000, Israel ent morphs – the one described to date in literature; and a second, previously undescribed morph, with female- Corresponding Author: [email protected] like barring on the chest and flanks interspersed with tear-shaped elongated spots, giving an overall female-like appearance. Here we forward the hypothesis that explain the evolutionary consequences for the female-like 2 FaunaViva - Viale Sar- plumage of juvenile males as that of intra-specific sex mimicry developed to avoid intra-specific predation by ca, 78 - 20125 Milano, the larger females. Italy, e-mail: lorenzo. [email protected] KEYWORDS Levant sparrowhawk – intraspecific predation – avoidance – morph © 2015 Reuven Yosef, Lorenzo Fornasari This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs license INTRODUCTION The Levant Sparrowhawk has dichromatism and re- Chromatic mimicry as a strategy to avoid inter-specific preda- versed sexual size dimorphism wherein the female is larger by tion, or to have a reproductive advantage, is well documented 9–10% than the male (Cramp & Simmons 1980; Clark & Yosef in many insect, amphibian and reptilian taxa (e.g.Gross & Char- 1997). The sexes also differ in colour, and the male has blue- nov 1980; Krebs & Davies 1987). -

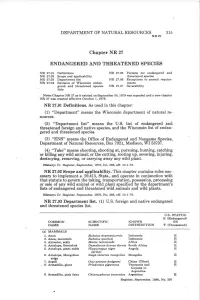

Endangered and Threatened Species

DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES 315 NR27 Chapter NR 27 ENDANGERED AND THREATENED SPECIES NR 27.01 Definitions NR 27 .05 Permits for endangered and NR 27.02 Scope end applicability threatened species NR 27.03 Department list NR 27 .06 Exceptions to permit require NR 27.04 Revision of Wisconsin endan ments gered and threatened species NR 27.07 Severability lists Note: Chapter NR 27 es it existed on September 30, 1979 was repealed and a new chapter NR 27 was created effective October 1, 1979. NR 27.01 Definitions. As used in this chapter: (1) "Department" means the Wisconsin department of natural re sources. (2) "Department list" means the U.S. list of endangered and threatened foreign and native species, and the Wisconsin list of endan gered and threatened species. (3) "ENS" means the Office of Endangered and Nongame Species, Department of Natural Resources, Box 7921, Madison, WI 53707. (4) "Take" means shooting, shooting at, pursuing, hunting, catching or killing any wild animal; or the cutting, rooting up, severing, injuring, destroying, removing, or carrying away any wild plant. Hlotory: Cr. Register, September, 1979, No. 285, eff. 10-1-79. NR 27.02 Scope and applicability. This chapter contains rules nec essary to implement s. 29.415, Stats., and operate in conjunction with that statute to govern the taking, transportation, possession, processing or sale of any wild animal or wild plant specified by the department's lists of endangered and threatened wild animals and wild plants. Hlotory: Cr. Register, September, 1979, No. 285, eff. 10-1-79. NR 27.03 Department list. -

Variation in the Procoracoid Foramen in the Accipitridae

Z6f Riv. Hal. Orn., Milano, 57 (3-4): 161-184, 15-XII-19B7 STORRS L. OLSON (*) VARIATION IN THE PROCORACOID FORAMEN IN THE ACCIPITRIDAE Abstract. — The procoracoid foramen of the eoracoid is present in the great majority of genera of Accipitridae. It may be nearly or completely absent in indivi- duals of Circus and Harpagus, the taxonomic significance of which is uncertain. The procoracoid foramen is invariably absent in the genus Accipiter, although the con- dition is still unknown in Erythrotriorchis and Megatriorchis which have sometimes been synonymized with Accipiter. The presence of a well developed procoracoid fo- ramen in Urotriorchis suggests that this genus may not be as closely related to Accipiter as has been assumed. Riassunto. — Variazione nel forame procoracoideo degli Accipitridae. II forame procoracoideo del coraeoide e presente nella maggioranza del generi degli Accipitridi. Esso puo essere quasi o completamente assente in individui di Circus e di Harpagus, fatto dal significato tassonomico incerto. II forame procora- coideo e invariabilmente assente nel genere Accipiter, sebbene tale condizione sia an- cora sconosciuta per i generi Erythrotriorchis e Megatriorchis, a volte posti in sino- nimia con Accipiter. La presenza di un forame procoracoideo ben sviluppato in Uro- triorchis suggerisce che questo genere possa non essere cosi strettamente affine ad Accipiter, come e stato ritenuto. Anatomical characters that may be of use in defining natural sub- divisions of the large and complex family Accipitridae are much to be desired, as, for example, the fused condition of the phalanges of the inner toe (OLSON 1982). Another feature that shows significant variation in the family is the procoracoid process of the eoracoid, the condition of which is worth documenting not just for systematic information but also for purposes of identification of archeological and paleontological materials. -

Birds Versus Bats: Attack Strategies of Bat-Hunting Hawks, and the Dilution Effect of Swarming

Supplementary Information Accompanying: Birds versus bats: attack strategies of bat-hunting hawks, and the dilution effect of swarming Caroline H. Brighton1*, Lillias Zusi2, Kathryn McGowan2, Morgan Kinniry2, Laura N. Kloepper2*, Graham K. Taylor1 1Department of Zoology, University of Oxford, South Parks Road, Oxford, OX1 3PS, UK. 2Department of Biology, Saint Mary’s College, Notre Dame, IN 46556, USA. *Correspondence to: [email protected] This file contains: Figures S1-S2 Tables S1-S3 Supplementary References supporting Table S1 Legend for Data S1 and Code S1 Legend for Movie S1 Data S1 and Code S1 implementing the statistical analysis have been uploaded as Supporting Information. Movie S1 has been uploaded to figshare: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.11823393 Figure S1. Video frames showing examples of attacks on lone bats and the column. (A,B) Attacks on the column of bats, defined as an attack on one or more bats within a cohesive group of individuals all flying in the same general direction. (C-E) Attacks on a lone bat (circled red), defined as an attack on an individual that appeared to be flying at least 1m from the edge of the column, and typically in a different direction to the swarm. (F) If an attack occurred in a volume containing many bats, but with no coherent flight direction, then this was also categorised as an attack on a lone bat, rather than as an attack on the swarm. Figure S2 Video frames used to estimate the proportion of bats meeting the criteria for classification as lone bats. -

Biodiversity Profile of Afghanistan

NEPA Biodiversity Profile of Afghanistan An Output of the National Capacity Needs Self-Assessment for Global Environment Management (NCSA) for Afghanistan June 2008 United Nations Environment Programme Post-Conflict and Disaster Management Branch First published in Kabul in 2008 by the United Nations Environment Programme. Copyright © 2008, United Nations Environment Programme. This publication may be reproduced in whole or in part and in any form for educational or non-profit purposes without special permission from the copyright holder, provided acknowledgement of the source is made. UNEP would appreciate receiving a copy of any publication that uses this publication as a source. No use of this publication may be made for resale or for any other commercial purpose whatsoever without prior permission in writing from the United Nations Environment Programme. United Nations Environment Programme Darulaman Kabul, Afghanistan Tel: +93 (0)799 382 571 E-mail: [email protected] Web: http://www.unep.org DISCLAIMER The contents of this volume do not necessarily reflect the views of UNEP, or contributory organizations. The designations employed and the presentations do not imply the expressions of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UNEP or contributory organizations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or its authority, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Unless otherwise credited, all the photos in this publication have been taken by the UNEP staff. Design and Layout: Rachel Dolores -

Raptors in the East African Tropics and Western Indian Ocean Islands: State of Ecological Knowledge and Conservation Status

j. RaptorRes. 32(1):28-39 ¸ 1998 The Raptor ResearchFoundation, Inc. RAPTORS IN THE EAST AFRICAN TROPICS AND WESTERN INDIAN OCEAN ISLANDS: STATE OF ECOLOGICAL KNOWLEDGE AND CONSERVATION STATUS MUNIR VIRANI 1 AND RICHARD T. WATSON ThePeregrine Fund, Inc., 566 WestFlying Hawk Lane, Boise,1D 83709 U.S.A. ABSTRACT.--Fromour reviewof articlespublished on diurnal and nocturnal birds of prey occurringin Africa and the western Indian Ocean islands,we found most of the information on their breeding biology comesfrom subtropicalsouthern Africa. The number of published papers from the eastAfrican tropics declined after 1980 while those from subtropicalsouthern Africa increased.Based on our KnoM- edge Rating Scale (KRS), only 6.3% of breeding raptorsin the eastAfrican tropicsand 13.6% of the raptorsof the Indian Ocean islandscan be consideredWell Known,while the majority,60.8% in main- land east Africa and 72.7% in the Indian Ocean islands, are rated Unknown. Human-caused habitat alteration resultingfrom overgrazingby livestockand impactsof cultivationare the main threatsfacing raptors in the east African tropics, while clearing of foreststhrough slash-and-burnmethods is most important in the Indian Ocean islands.We describeconservation recommendations, list priorityspecies for study,and list areasof ecologicalunderstanding that need to be improved. I•y WORDS: Conservation;east Africa; ecology; western Indian Ocean;islands; priorities; raptors; research. Aves rapacesen los tropicos del este de Africa yen islasal oeste del Oc•ano Indico: estado del cono- cimiento eco16gicoy de su conservacitn RESUMEN.--Denuestra recopilacitn de articulospublicados sobre aves rapaces diurnas y nocturnasque se encuentran en Africa yen las islasal oeste del Octano Indico, encontramosque la mayoriade la informaci6n sobre aves rapacesresidentes se origina en la regi6n subtropical del sur de Africa.