Biodiversity Profile of Afghanistan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Inclusion of Asiatic Mammal Species on Cms Appendices

Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals Secretariat provided by the United Nations Environment Programme 14 th MEETING OF THE CMS SCIENTIFIC COUNCIL Bonn, Germany, 14-17 March 2007 CMS/ScC14/Doc.13 Agenda item 6(a) DRAFT PROPOSALS FOR THE INCLUSION OF ASIATIC MAMMAL SPECIES ON CMS APPENDICES (Prepared by the Secretariat) 1. The four draft proposals for the amendment of CMS Appendices attached to this note have been prepared by the Institut Royal des Sciences Naturelles de Belgique and have been submitted by Dr. Pierre Devillers, Scientific Councillor for the European Community and vice-chairman of the Scientific Council. 2. Preparation of these draft proposals is undertaken within the Central Eurasian Aridland Concerted Action and associated Cooperative Action approved by the 8 th Meeting of the Conference of the Parties to CMS (Recommendation 8.23), covering threatened migratory large mammals of the temperate and cold deserts, semi-deserts, steppes and associated mountains of Central Asia, the Northern Indian sub-continent, Western Asia, the Caucasus and Eastern Europe. 3. In particular, Rec. 8.23 “encourages Range States and other interested Parties to prepare, in cooperation with the Scientific Council and the Secretariat, the necessary proposals to include in Appendix I or Appendix II threatened species that would benefit from the Action”. For reasons of economy, documents are printed in a limited number, and will not be distributed at the meeting. Delegates are kindly requested to bring their copy to the meeting and not to request additional copies. DRAFT PROPOSAL FOR INCLUSION OF SPECIES ON THE APPENDICES OF THE CONVENTION ON THE CONSERVATION OF MIGRATORY SPECIES OF WILD ANIMALS Proposal to add in Appendix I Pantholops hodgsonii Document largely based on the species information provided in IUCN Redlist of Threatened Species database (2006) February 2007 2 1. -

An Inventory of Avian Species in Aldesa Valley, Saudi Arabia

14 5 LIST OF SPECIES Check List 14 (5): 743–750 https://doi.org/10.15560/14.5.743 An inventory of avian species in Aldesa Valley, Saudi Arabia Abdulaziz S. Alatawi1, Florent Bled1, Jerrold L. Belant2 1 Mississippi State University, Forest and Wildlife Research Center, Carnivore Ecology Laboratory, Box 9690, Mississippi State, MS, USA 39762. 2 State University of New York, College of Environmental Science and Forestry, 1 Forestry Drive, Syracuse, NY, USA 13210. Corresponding author: Abdulaziz S. Alatawi, [email protected] Abstract Conducting species inventories is important to provide baseline information essential for management and conserva- tion. Aldesa Valley lies in the Tabuk Province of northwest Saudi Arabia and because of the presence of permanent water, is thought to contain high avian richness. We conducted an inventory of avian species in Aldesa Valley, using timed area-searches during May 10–August 10 in 2014 and 2015 to detect species occurrence. We detected 6860 birds belonging to 19 species. We also noted high human use of this area including agriculture and recreational activities. Maintaining species diversity is important in areas receiving anthropogenic pressures, and we encourage additional surveys to further identify species occurrence in Aldesa Valley. Key words Arabian Peninsula; bird inventory; desert fauna. Academic editor: Mansour Aliabadian | Received 21 April 2016 | Accepted 27 May 2018 | Published 14 September 2018 Citation: Alatawi AS, Bled F, Belant JL (2018) An inventory of avian species in Aldesa Valley, Saudi Arabia. Check List 14 (5): 743–750. https:// doi.org/10.15560/14.5.743 Introduction living therein (Balvanera et al. -

(Lepidoptera: Insecta) from Jammu and Kashmir Himalaya

Rec. zool. Surv. India: Vol 119(4)/ 463-473, 2019 ISSN (Online) : 2581-8686 DOI: 10.26515/rzsi/v119/i4/2019/144197 ISSN (Print) : 0375-1511 New records of butterflies (Lepidoptera: Insecta) from Jammu and Kashmir Himalaya Taslima Sheikh and Sajad H. Parey* Baba Ghulam Shah Badshah University, Rajouri – 185234, Jammu and Kashmir, India; [email protected] Abstract Himalayas represents one of the unique ecosystems in terms of species diversity and species richness. While studying taxa of butterflies in Jammu and Rajouri districts located in Western Himalaya, fourteen species (Abisara bifasciata Moore, Pareronia hippia Fabricius, Elymnias hypermnestra Linnaeus, Acraea terpsicore Linnaeus, Charaxes solon Fabricius, Symphaedra nais Forster, Neptis jumbah Moore, Moduza procris Cramer, Athyma cama Moore, Tajuria jehana Moore, Arhopala amantes Hewitson, Jamides celeno Cramer, Everes lacturnus Godart and Udaspes folus Cramer) are recorded for the first time from the Union territory of Jammu and Kashmir. Investigations for butterflies were carried by following visual encounter method between 2014 and 2019 in morning hours from 7 am to 11 am throughout breeding seasons in Jammu and Rajouri districts. This communication deals with peculiar taxonomical identity, common name, global distribution, IUCN status and photographs of newly recorded butterflies. Keywords: Butterflies, Himalayas, New Record, Species, Jammu & Kashmir Introduction India are 1,439 (Evans, 1932; Kunte, 2018) from oasis, high mountains, highlands, tropical to alpine forests, Butterflies (Class: INSECTA Linnaeus, 1758, Order: swamplands, plains, grasslands, and areas surrounding LEPIDOPTERA Linnaeus, 1758) are holometabolous rivers. group of living organism as they complete metamorphosis cycles in four stages, viz. egg or embryo, larva or Jammu and Kashmir known as ‘Terrestrial Paradise caterpillar, pupa or chrysalis and imago or adult (Gullan on Earth’ categorized to as a part of the Indian Himalayan and Cranston, 2004; Capinera, 2008). -

Qrno. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 1 CP 2903 77 100 0 Cfcl3

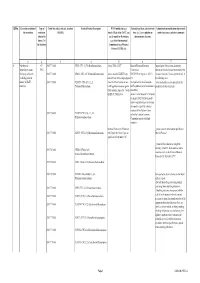

QRNo. General description of Type of Tariff line code(s) affected, based on Detailed Product Description WTO Justification (e.g. National legal basis and entry into Administration, modification of previously the restriction restriction HS(2012) Article XX(g) of the GATT, etc.) force (i.e. Law, regulation or notified measures, and other comments (Symbol in and Grounds for Restriction, administrative decision) Annex 2 of e.g., Other International the Decision) Commitments (e.g. Montreal Protocol, CITES, etc) 12 3 4 5 6 7 1 Prohibition to CP 2903 77 100 0 CFCl3 (CFC-11) Trichlorofluoromethane Article XX(h) GATT Board of Eurasian Economic Import/export of these ozone destroying import/export ozone CP-X Commission substances from/to the customs territory of the destroying substances 2903 77 200 0 CF2Cl2 (CFC-12) Dichlorodifluoromethane Article 46 of the EAEU Treaty DECISION on August 16, 2012 N Eurasian Economic Union is permitted only in (excluding goods in dated 29 may 2014 and paragraphs 134 the following cases: transit) (all EAEU 2903 77 300 0 C2F3Cl3 (CFC-113) 1,1,2- 4 and 37 of the Protocol on non- On legal acts in the field of non- _to be used solely as a raw material for the countries) Trichlorotrifluoroethane tariff regulation measures against tariff regulation (as last amended at 2 production of other chemicals; third countries Annex No. 7 to the June 2016) EAEU of 29 May 2014 Annex 1 to the Decision N 134 dated 16 August 2012 Unit list of goods subject to prohibitions or restrictions on import or export by countries- members of the -

Grassland Resources and Development of Grassland Agriculture in Temperate China

124 Rangelands 10(3), June 1988 Grassland Resources and Development of Grassland Agriculture in Temperate China Zhu Tinachen Natural temperate grasslands occupy 2.4 million km2 or one-quarter ofthe area of China. They form a broad beltfrom the plains of the northeast to the Tibetan Plateau of the southwest (Fig. 1). The nature and distribution of thegrassland is determined in large part by the influence of the monsoon. In the north- east where the monsoon is well developed, the grassland owes its existenceto dry conditions in the spring. Westward and southwestward wherethe monsooninfluence is weaker, the grasslandsoccupy higherelevations (to as high as 5,000 m) in response to the semiarid and arid regional climate. Similarly, temperate grasslands occur at high elevations in mountains of the desert region in northwestern China, far beyond the continuous grassland belt. Some 4,000 species offlowering plants comprise thevegetation ofthese temper- ate grasslands.About 200 are important forage species. The livestock population in China is about 130 million Fig. I Steppe zone of China cattle units. Most of the livestock are dependent on these 1.Meadow steppe, 2.Typical steppe. 3.Desert steppe. 4. Shrub steppe. 5. Alpine steppe. natural temperategrasslands. GrasslandTypes responding to climate and distributed in the form of a belt. Meadows are not zonal; they are controlled by local envi- Based on the concept of zonal vegetation, the natural ronments.About 80 ofthe area of is occu- of China can be divided into two percent grassland temperategrasslands major pied by zone steppetypes and about 20 percent by meadow types: steppe and meadow. -

Insects & Spiders of Kanha Tiger Reserve

Some Insects & Spiders of Kanha Tiger Reserve Some by Aniruddha Dhamorikar Insects & Spiders of Kanha Tiger Reserve Aniruddha Dhamorikar 1 2 Study of some Insect orders (Insecta) and Spiders (Arachnida: Araneae) of Kanha Tiger Reserve by The Corbett Foundation Project investigator Aniruddha Dhamorikar Expert advisors Kedar Gore Dr Amol Patwardhan Dr Ashish Tiple Declaration This report is submitted in the fulfillment of the project initiated by The Corbett Foundation under the permission received from the PCCF (Wildlife), Madhya Pradesh, Bhopal, communication code क्रम 車क/ तकनीकी-I / 386 dated January 20, 2014. Kanha Office Admin office Village Baherakhar, P.O. Nikkum 81-88, Atlanta, 8th Floor, 209, Dist Balaghat, Nariman Point, Mumbai, Madhya Pradesh 481116 Maharashtra 400021 Tel.: +91 7636290300 Tel.: +91 22 614666400 [email protected] www.corbettfoundation.org 3 Some Insects and Spiders of Kanha Tiger Reserve by Aniruddha Dhamorikar © The Corbett Foundation. 2015. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used, reproduced, or transmitted in any form (electronic and in print) for commercial purposes. This book is meant for educational purposes only, and can be reproduced or transmitted electronically or in print with due credit to the author and the publisher. All images are © Aniruddha Dhamorikar unless otherwise mentioned. Image credits (used under Creative Commons): Amol Patwardhan: Mottled emigrant (plate 1.l) Dinesh Valke: Whirligig beetle (plate 10.h) Jeffrey W. Lotz: Kerria lacca (plate 14.o) Piotr Naskrecki, Bud bug (plate 17.e) Beatriz Moisset: Sweat bee (plate 26.h) Lindsay Condon: Mole cricket (plate 28.l) Ashish Tiple: Common hooktail (plate 29.d) Ashish Tiple: Common clubtail (plate 29.e) Aleksandr: Lacewing larva (plate 34.c) Jeff Holman: Flea (plate 35.j) Kosta Mumcuoglu: Louse (plate 35.m) Erturac: Flea (plate 35.n) Cover: Amyciaea forticeps preying on Oecophylla smargdina, with a kleptoparasitic Phorid fly sharing in the meal. -

Further Assessment of the Genus Neodon and the Description of a New Species from Nepal

RESEARCH ARTICLE Further assessment of the Genus Neodon and the description of a new species from Nepal 1³ 2 2 3 Nelish PradhanID , Ajay N. Sharma , Adarsh M. Sherchan , Saurav Chhetri , 4 1³ Paliza Shrestha , C. William KilpatrickID * 1 Department of Biology, University of Vermont, Burlington, Vermont, United States of America, 2 Center for Molecular Dynamics±Nepal, Kathmandu, Nepal, 3 Department of Biology, Trinity University, San Antonio, Texas, United States of America, 4 Department of Plant and Soil Science, University of Vermont, Burlington, Vermont, United States of America a1111111111 ³ These authors are joint senior authors on this work. a1111111111 * [email protected] a1111111111 a1111111111 a1111111111 Abstract Recent molecular systematic studies of arvicoline voles of the genera Neodon, Lasiopod- omys, Phaiomys, and Microtus from Central Asia suggest the inclusion of Phaiomys leu- OPEN ACCESS curus, Microtus clarkei, and Lasiopodomys fuscus into Neodon and moving Neodon juldaschi into Microtus (Blanfordimys). In addition, three new species of Neodon (N. linz- Citation: Pradhan N, Sharma AN, Sherchan AM, Chhetri S, Shrestha P, Kilpatrick CW (2019) Further hiensis, N. medogensis, and N. nyalamensis) have recently been described from Tibet. assessment of the Genus Neodon and the Analyses of concatenated mitochondrial (Cytb, COI) and nuclear (Ghr, Rbp3) genes recov- description of a new species from Nepal. PLoS ered Neodon as a well-supported monophyletic clade including all the recently described ONE 14(7): e0219157. https://doi.org/10.1371/ and relocated species. Kimura-2-parameter distance between Neodon from western Nepal journal.pone.0219157 compared to N. sikimensis (K2P = 13.1) and N. irene (K2P = 13.4) was equivalent to genetic Editor: Johan R. -

The Republic of Tajikistan Ministry of Energy and Industry

The Republic of Tajikistan Ministry of Energy and Industry DATA COLLECTION SURVEY ON THE INSTALLMENT OF SMALL HYDROPOWER STATIONS FOR THE COMMUNITIES OF KHATLON OBLAST IN THE REPUBLIC OF TAJIKISTAN FINAL REPORT September 2012 Japan International Cooperation Agency NEWJEC Inc. E C C CR (1) 12-005 Final Report Contents, List of Figures, Abbreviations Data Collection Survey on the Installment of Small Hydropower Stations for the Communities of Khatlon Oblast in the Republic of Tajikistan FINAL REPORT Table of Contents Summary Chapter 1 Preface 1.1 Objectives and Scope of the Study .................................................................................. 1 - 1 1.2 Arrangement of Small Hydropower Potential Sites ......................................................... 1 - 2 1.3 Flowchart of the Study Implementation ........................................................................... 1 - 7 Chapter 2 Overview of Energy Situation in Tajikistan 2.1 Economic Activities and Electricity ................................................................................ 2 - 1 2.1.1 Social and Economic situation in Tajikistan ....................................................... 2 - 1 2.1.2 Energy and Electricity ......................................................................................... 2 - 2 2.1.3 Current Situation and Planning for Power Development .................................... 2 - 9 2.2 Natural Condition ............................................................................................................ -

Morphology, Diet Composition, Distribution and Nesting Biology of Four Lark Species in Mongolia

© 2013 Journal compilation ISSN 1684-3908 (print edition) http://biology.num.edu.mn Mongolian Journal of Biological http://mjbs.100zero.org/ Sciences MJBS Volume 11(1-2), 2013 ISSN 2225-4994 (online edition) Original ArƟ cle Morphology, Diet Composition, Distribution and Nesting Biology of Four Lark Species in Mongolia Galbadrakh Mainjargal1, Bayarbaatar Buuveibaatar2* and Shagdarsuren Boldbaatar1 1Laboratory of Ornithology, Institute of Biology, Mongolian Academy of Sciences, Jukov Avenue, Ulaanbaatar 51, Mongolia, Email: [email protected] 2Mongolia Program, Wildlife Conservation Society, San Business Center 201, Amar Str. 29, Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia, email: [email protected] Abstract Key words: We aimed to enhance existing knowledge of four lark species (Mongolian lark, Horned Alaudidae, larks, lark, Eurasian skylark, and Lesser short-toed lark), with respect to nesting biology, breeding, food habits, distribution, and diet, using long-term dataset collected during 2000–2012. Nest and Mongolia egg measurements substantially varied among species. For pooled data across species, the clutch size averaged 3.72 ± 1.13 eggs and did not differ among larks. Body mass of nestlings increased signifi cantly with age at weighing. Daily increase in body mass Article information: of lark nestlings ranged between 3.09 and 3.89 gram per day. Unsurprisingly, the Received: 18 Nov. 2013 majority of lark locations occurred in steppe ecosystems, followed by human created Accepted: 11 Dec. 2013 systems; whereas only 1.8% of the pooled locations across species were observed in Published: 20 Apr. 2014 forest ecosystem. Diet composition did not vary among species in the proportions of major food categories consumed. The most commonly occurring food items were invertebrates and frequently consumed were being beetles (e.g. -

Observations on Lycaenid Butterflies from Panbari Reserve Forest and Adjoining Areas, Kaziranga, Assam, Northeastern

Journal of Threatened Taxa | www.threatenedtaxa.org | 26 December 2015 | 7(15): 8259–8271 Observations on lycaenid butterflies from Panbari Reserve Forest and adjoining areas, Kaziranga, Assam, northeastern India ISSN 0974-7907 (Online) ISSN 0974-7893 (Print) Communication Short Monsoon Jyoti Gogoi OPEN ACCESS Ph.D Student, Department of Ecology & Environmental Science, Assam University, Silchar, Assam 788011, India [email protected] Abstract: A checklist of 116 taxa of Lycaenidae (Blues) along with made to document the Lycaenidae notes on important species in low elevation forest of Panbari Reserve, of Kaziranga-Karbi Hills Kaziranga - West Karbi Hills, upper Assam is reported in this paper based on surveys conducted during 2007–2012 and some recent sightings till date. Important sightings include Blue Gem Poritia Methods erycinoides elsiei, Square-band Brownie Miletis nymphys porus, Plain Plushblue Flos apidanus ahamus, Blue Royal Ancema carmentalis, Study area Elwes Silverline Spindasis elwesi, Artipe skinneri, etc. The Panbari Reserve Forest (26036’N & 93030’E) is protected under the Kaziranga National Park (KNP) Keywords: Butterfly diversity, Kaziranga, Lycaenidae, northeastern India, Panbari Reserve. as its fourth addition (Images 1a,b & 2). The average elevation of the forest is around 90m. The altitude however ranges from 70–300 m. The reserve is very close to National Highway 37 (NH37) on the Guwahati- The Lycaenidae (Blues) butterfly diversity in low Jorhat route. The reserve falls between Golaghat and elevation forests of Panbari Reserve, Kaziranga - West Karb Anglong (KA) districts of Assam. To the north of Karbi Hills, upper Assam is reported in this paper. Karbi the reserve lies Dollamora proposed reserve in Karbi Hills constitue a chain of hill ranges lying in middle Assam Anglong District and on the southern boundary is a in the southern bank of the river Brahmaputra. -

Genus/Species Skull Ht Lt Wt Stage Range Abalosia U.Pliocene S America Abelmoschomys U.Miocene E USA A

Genus/Species Skull Ht Lt Wt Stage Range Abalosia U.Pliocene S America Abelmoschomys U.Miocene E USA A. simpsoni U.Miocene Florida(US) Abra see Ochotona Abrana see Ochotona Abrocoma U.Miocene-Recent Peru A. oblativa 60 cm? U.Holocene Peru Abromys see Perognathus Abrosomys L.Eocene Asia Abrothrix U.Pleistocene-Recent Argentina A. illuteus living Mouse Lujanian-Recent Tucuman(ARG) Abudhabia U.Miocene Asia Acanthion see Hystrix A. brachyura see Hystrix brachyura Acanthomys see Acomys or Tokudaia or Rattus Acarechimys L-M.Miocene Argentina A. minutissimus Miocene Argentina Acaremys U.Oligocene-L.Miocene Argentina A. cf. Murinus Colhuehuapian Chubut(ARG) A. karaikensis Miocene? Argentina A. messor Miocene? Argentina A. minutissimus see Acarechimys minutissimus Argentina A. minutus Miocene? Argentina A. murinus Miocene? Argentina A. sp. L.Miocene Argentina A. tricarinatus Miocene? Argentina Acodon see Akodon A. angustidens see Akodon angustidens Pleistocene Brazil A. clivigenis see Akodon clivigenis Pleistocene Brazil A. internus see Akodon internus Pleistocene Argentina Acomys L.Pliocene-Recent Africa,Europe,W Asia,Crete A. cahirinus living Spiny Mouse U.Pleistocene-Recent Israel A. gaudryi U.Miocene? Greece Aconaemys see Pithanotomys A. fuscus Pliocene-Recent Argentina A. f. fossilis see Aconaemys fuscus Pliocene Argentina Acondemys see Pithanotomys Acritoparamys U.Paleocene-M.Eocene W USA,Asia A. atavus see Paramys atavus A. atwateri Wasatchian W USA A. cf. Francesi Clarkforkian Wyoming(US) A. francesi(francesci) Wasatchian-Bridgerian Wyoming(US) A. wyomingensis Bridgerian Wyoming(US) Acrorhizomys see Clethrionomys Actenomys L.Pliocene-L.Pleistocene Argentina A. maximus Pliocene Argentina Adelomyarion U.Oligocene France A. vireti U.Oligocene France Adelomys U.Eocene France A. -

Re Building the Afghan Army

5HEXLOGLQJWKH$IJKDQDUP\ 'U$QWRQLR*LXVWR]]L&ULVLV6WDWHV3URJUDPPH'HYHORSPHQW5HVHDUFK&HQWUH /6( 7KHDUP\XQGHUWKHPRQDUFK\DQGWKHILUVWUHSXEOLF Some sort of regular army was first established in Afghanistan during the 1860s and 1870s and fought in the Second Anglo-Afghan war. Attempts were made to train this force to European standards, using translated manuals, but the new organisation was never really implemented and the army collapsed early in the war against the British. Another attempt to create a regular army awas made in the 1880s and 1890s by Abdur Rahman Khan, with greater but still limited success, despite British subsidies. After the Third Anglo-Afghan war (1919) the army experienced a rapid decline, both because of huge budget cuts and of the internal conflict that climaxed in the 1928-29 civil war. The origins of the modern Afghan regular armed forces date back to the 1920s and 1930s, when the first serious (still not very successful) attempts to establish a disciplined military force were carried out. After virtually disintegrating during 1928- 1929, the army was re-built during the 1930s, under the leadership of king Nadir Shah. The military academy, in charge of educating the lower ranks of the officer corps, was established in 1932, while the top brass were trained in Turkey. By 1938 the Afghan army numbered 90,000 men, a size that would be maintained until the late 1970s. The police was instead a much smaller force of 9,600 men, based in the cities and towns. The Afghan Royal Air Force was created in 1924 and soon acquired its first bombers, whose potential in dealing with tribal revolts had become clear during the Third Anglo-Afghan war (1919), in which the intervention of the British RAF had proved decisive.