New Legislation in Germany Concerning Same-Sex Unions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gesetzentwurf

Deutscher Bundestag Drucksache 14/4097 14. Wahlperiode 15. 09. 2000 Gesetzentwurf der Abgeordneten Peter Rauen, Gerda Hasselfeldt, Dietrich Austermann, Hansjürgen Doss, Norbert Geis, Ernst Hinsken, Karl-Josef Laumann, Norbert Barthle, Otto Bernhardt, Leo Dautzenberg, Jochen-Konrad Fromme, Hansgeorg Hauser (Rednitzhembach), Bartholomäus Kalb, Dr. Michael Luther, Hans Michelbach, Norbert Schindler, Diethard Schütze (Berlin), Wolfgang Schulhoff, Heinz Seiffert, Klaus-Peter Willsch, Elke Wülfing und der Fraktion der CDU/CSU Entwurf eines Gesetzes zur Senkung der Mineralölsteuer und zur Abschaffung der Stromsteuer (Ökosteuer-Abschaffungsgesetz) A. Problem Mit dem Gesetz zum Einstieg in die ökologische Steuerreform vom 24. März 1999 (BGBl. I S. 378) und dem Gesetz zur Fortführung der ökologischen Steu- erreform vom 16. Dezember 1999 (BGBl. I S. 2432) wurde die Mineralölsteuer erhöht und eine Stromsteuer eingeführt sowie erhöht. Diese Steuererhöhungen wurden mit dem Titel einer sog. Ökosteuer versehen. Die Entwicklung des Rohölpreises, das Wechselkursverhältnis des Euro zum Dollar sowie die durch die vorgenannten Gesetze vorgenommenen und für die Jahre 2001 bis 2003 vorgesehenen Steuererhöhungen stellen eine Gefahr für das Wirtschaftswachs- tum in Deutschland dar und belasten Bürger und Betriebe in unverantwortlicher Weise. Die bisherigen Erhöhungen der Mineralölsteuer und der Stromsteuer müssen daher rückgängig gemacht werden und die noch vorgesehenen Erhö- hungen müssen unterbleiben. B. Lösung Die bereits zum 1. 4. 1999 und am 1. 1. 2000 vorgenommenen Erhöhungen der Mineralölsteuer bzw. der Stromsteuer werden zum 1. 1. 2001 rückgängig ge- macht. Ebenso werden die für den 1. 1. 2001, 1. 1. 2002 und 1. 1. 2003 be- schlossenen Steuererhöhungen wieder aufgehoben. Die Steuersätze entspre- chen danach ab 1. 1. 2001 wieder der Gesetzeslage zum 31. -

Commentary by Miriam Saage-Maaβ Vice Legal Director & Coordinator of Business & Human Rights Program European Center for Constitutional and Human Rights July 2012

How serious is the international community of states about human rights standards for business? commentary by Miriam Saage-Maaβ Vice Legal Director & coordinator of Business & Human Rights program European Center for Constitutional and Human Rights July 2012 Recent developments have shown one more time that the struggle for human rights is not only about the creation of international standards so that the rule of law may prevail. The struggle for human rights is also a struggle between different economic and political interests, and it is a question of power which interests prevail. 2011 was an important year for the development of standards in the field of business and human rights. In May 2011 the OECD member states approved a revised version of the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises, introducing a new human rights chapter. Only a month later the United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHRC) endorsed by consensus the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights.1 These two international documents are both designed to provide a global standard for preventing and addressing the risk of business-related human rights violations. In particular, the UN Guiding Principles focus on the “State Duty to Protect” and the “Corporate Responsibility to Respect” in addition to the “Access to Remedy” principle. This principle seeks to ensure that when people are harmed by business activity, there is both adequate accountability and effective redress, both judicial and non-judicial. The Guiding Principles clearly call on states to ensure -

Papers Situation Gruenen

PAPERS JOCHEN WEICHOLD ZUR SITUATION DER GRÜNEN IM HERBST 2014 ROSA LUXEMBURG STIFTUNG JOCHEN WEICHOLD ZUR SITUATION DER GRÜNEN IM HERBST 2014 REIHE PAPERS ROSA LUXEMBURG STIFTUNG Zum Autor: Dr. JOCHEN WEICHOLD ist freier Politikwissenschaftler. IMPRESSUM PAPERS wird herausgegeben von der Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung und erscheint unregelmäßig V. i. S . d. P.: Martin Beck Franz-Mehring-Platz 1 • 10243 Berlin • www.rosalux.de ISSN 2194-0916 • Redaktionsschluss: November 2014 Gedruckt auf Circleoffset Premium White, 100 % Recycling 2 Inhalt Einleitung 5 Wahlergebnisse der Grünen bei Europa- und bei Bundestagswahlen 7 Ursachen für die Niederlage der Grünen bei der Bundestagswahl 2013 11 Wählerwanderungen von und zu den Grünen bei Europa- und bei Bundestagswahlen 16 Wahlergebnisse der Grünen bei Landtags- und bei Kommunalwahlen 18 Zur Sozialstruktur der Wähler der Grünen 24 Mitgliederentwicklung der Grünen 32 Zur Sozialstruktur der Mitglieder der Grünen 34 Politische Positionen der Partei Bündnis 90/Die Grünen 36 Haltung der Grünen zu aktuellen Fragen 46 Innerparteiliche Differenzierungsprozesse bei den Grünen 48 Ausblick: Schwarz-Grün auf Bundesebene? 54 Anhang 58 Zusammensetzung des Bundesvorstandes der Grünen (seit Oktober 2013) 58 Zusammensetzung des Parteirates der Grünen (seit Oktober 2013) 58 Abgeordnete der Grünen im Deutschen Bundestag im Ergebnis der Bundestagswahl 2013 59 Abgeordnete der Grünen im Europäischen Parlament im Ergebnis der Europawahl 2014 61 Wählerwanderungen von bzw. zu den Grünen bei der Landtagswahl in Sachsen 2014 im Vergleich zur Landtagswahl 2009 62 3 Wählerwanderungen von bzw. zu den Grünen bei der Landtagswahl in Brandenburg 2014 im Vergleich zur Landtagswahl 2009 62 Wählerwanderungen von bzw. zu den Grünen bei der Landtagswahl in Thüringen 2014 im Vergleich zur Landtagswahl 2009 63 Zur Sozialstruktur der Grün-Wähler bei den Landtagswahlen in Branden- burg, Sachsen und Thüringen 2014 63 Anmerkungen 65 4 Einleitung Die Partei Bündnis 90/Die Grünen (Grüne) stellt zwar mit 63 Abgeordneten die kleinste Fraktion im Deutschen Bundestag. -

Vorabveröffentlichung

Deutscher Bundestag – 16. Wahlperiode – 227. Sitzung. Berlin, Donnerstag, den 18. Juni 2009 25025 (A) (C) Redetext 227. Sitzung Berlin, Donnerstag, den 18. Juni 2009 Beginn: 9.00 Uhr Präsident Dr. Norbert Lammert: Afghanistan (International Security Assis- Die Sitzung ist eröffnet. Guten Morgen, liebe Kolle- tance Force, ISAF) unter Führung der NATO ginnen und Kollegen. Ich begrüße Sie herzlich. auf Grundlage der Resolutionen 1386 (2001) und folgender Resolutionen, zuletzt Resolution Bevor wir in unsere umfangreiche Tagesordnung ein- 1833 (2008) des Sicherheitsrates der Vereinten treten, habe ich einige Glückwünsche vorzutragen. Die Nationen Kollegen Bernd Schmidbauer und Hans-Christian Ströbele haben ihre 70. Geburtstage gefeiert. – Drucksache 16/13377 – Überweisungsvorschlag: (Beifall) Auswärtiger Ausschuss (f) Rechtsausschuss Man will es kaum für möglich halten. Aber da unsere Verteidigungsausschuss Datenhandbücher im Allgemeinen sehr zuverlässig sind, Ausschuss für Menschenrechte und Humanitäre Hilfe (B) muss ich von der Glaubwürdigkeit dieser Angaben aus- Ausschuss für wirtschaftliche Zusammenarbeit und (D) gehen. Entwicklung Haushaltsausschuss gemäß § 96 GO Ihre 60. Geburtstage haben der Kollege Christoph (siehe 226. Sitzung) Strässer und die Bundesministerin Ulla Schmidt gefei- ert; ZP 3 Weitere Überweisungen im vereinfachten Ver- fahren (Beifall) (Ergänzung zung TOP 66) ich höre, sie seien auch schön gefeiert worden, was wir u damit ausdrücklich im Protokoll vermerkt haben. a) Beratung des Antrags der Abgeordneten Dr. Gesine Lötzsch, -

Plenarprotokoll 16/220

Plenarprotokoll 16/220 Deutscher Bundestag Stenografischer Bericht 220. Sitzung Berlin, Donnerstag, den 7. Mai 2009 Inhalt: Glückwünsche zum Geburtstag der Abgeord- ter und der Fraktion DIE LINKE: neten Walter Kolbow, Dr. Hermann Scheer, Bundesverantwortung für den Steu- Dr. h. c. Gernot Erler, Dr. h. c. Hans ervollzug wahrnehmen Michelbach und Rüdiger Veit . 23969 A – zu dem Antrag der Abgeordneten Dr. Erweiterung und Abwicklung der Tagesord- Barbara Höll, Dr. Axel Troost, nung . 23969 B Dr. Gregor Gysi, Oskar Lafontaine und der Fraktion DIE LINKE: Steuermiss- Absetzung des Tagesordnungspunktes 38 f . 23971 A brauch wirksam bekämpfen – Vor- handene Steuerquellen erschließen Tagesordnungspunkt 15: – zu dem Antrag der Abgeordneten Dr. a) Erste Beratung des von den Fraktionen der Barbara Höll, Wolfgang Nešković, CDU/CSU und der SPD eingebrachten Ulla Lötzer, weiterer Abgeordneter Entwurfs eines Gesetzes zur Bekämp- und der Fraktion DIE LINKE: Steuer- fung der Steuerhinterziehung (Steuer- hinterziehung bekämpfen – Steuer- hinterziehungsbekämpfungsgesetz) oasen austrocknen (Drucksache 16/12852) . 23971 A – zu dem Antrag der Abgeordneten b) Beschlussempfehlung und Bericht des Fi- Christine Scheel, Kerstin Andreae, nanzausschusses Birgitt Bender, weiterer Abgeordneter und der Fraktion BÜNDNIS 90/DIE – zu dem Antrag der Fraktionen der GRÜNEN: Keine Hintertür für Steu- CDU/CSU und der SPD: Steuerhin- erhinterzieher terziehung bekämpfen (Drucksachen 16/11389, 16/11734, 16/9836, – zu dem Antrag der Abgeordneten Dr. 16/9479, 16/9166, 16/9168, 16/9421, Volker Wissing, Dr. Hermann Otto 16/12826) . 23971 B Solms, Carl-Ludwig Thiele, weiterer Abgeordneter und der Fraktion der Lothar Binding (Heidelberg) (SPD) . 23971 D FDP: Steuervollzug effektiver ma- Dr. Hermann Otto Solms (FDP) . 23973 A chen Eduard Oswald (CDU/CSU) . -

CSU-Landesgruppe Startet Kraftvoll in Die Neue Legislaturperiode Die CSU-Landesgruppe Ist Im 18

Nr. 14| 23.10.2013 | AusgAbe A Konstituierende Sitzung des Bundestages Csu-Landesgruppe startet kraftvoll in die neue Legislaturperiode Die CSU-Landesgruppe ist im 18. Deutschen bundestag stark ver- treten: Mit insgesamt 56 CSU-bundestagsabgeordneten startet die Landesgruppe in die nächste Legislaturperiode – das sind zwölf christlich-soziale Abgeordnete mehr als bisher. Am Dienstag, den 22. Oktober 2013, ist der 18. Deutsche bundestag erstmals im Sehr geehrte Damen und Herren, berliner reichstag zusammengetreten. in einer großen gemeinsamen Kraftanstrengung ist es uns miteinander gelungen, den Wahlkreis 218 München/Nord-Mitte wieder für die CSU direkt zu gewinnen. Das Wahlergebnis hat fol- gende drei Kernpunkte: 43,2% der Erststimmen konnten von uns ge- wonnen werden, der SPD-Bewerber erreichte 31,4%. Unser Vorsprung hat sich damit von 0,9% im Jahre 2009 zweistellig auf einen Vor- sprung von 11,8% mehr als verzehnfacht. Foto: picture alliance / dpa Im Münchner Norden liegen wir mit 18.305 Landesgruppenvorsitzende Gerda Hasselfeldt und Geschäftsführer Stefan Müller neben Bundeskanzlerin Angela Merkel bei der ersten Sitzung des 18. Deutschen Bundestags am Erststimmen vorne (2009 waren es 1.470 Stim- Dienstag in Berlin men Vorsprung) und konnten rund 10.000 Erst- stimmen zusätzlich zu den CSU-Zweitstimmen 30 Tage nach der Bundestagswahl Jahre. Ihre männlichen Kollegen in hinzugewinnen. ist das neu gewählte Parlament der Landesgruppe sind im Schnitt am Dienstag in Berlin zu seiner 48,98 Jahre alt – damit sind sie Alle Stadtbezirke im Wahlkreis München-Nord konstituierenden Sitzung zusam- die zweitjüngste männliche Al- gingen sowohl bei der Erststimme wie auch bei mengetreten. Von den insgesamt tersgruppe. Als erste Amtshand- der Zweitstimme an uns. -

Kettenduldungen Abschaffen

Deutscher Bundestag Drucksache 16/687 16. Wahlperiode 16. 02. 2006 Antrag der Abgeordneten Josef Philip Winkler, Volker Beck (Köln), Britta Haßelmann, Monika Lazar, Jerzy Montag, Claudia Roth (Augsburg), Irmingard Schewe-Gerigk, Hans-Christian Ströbele, Silke Stokar von Neuforn, Wolfgang Wieland und der Fraktion BÜNDNIS 90/DIE GRÜNEN Kettenduldungen abschaffen Der Bundestag wolle beschließen: I. Der Deutsche Bundestag stellt fest: Die Anwendung des § 25 des Aufenthaltsgesetzes (AufenthG) durch die Länder steht nicht in Einklang mit dem Ziel des Gesetzgebers, die Kettenduldungen ab- zuschaffen. II. Der Bundestag fordert die Bundesregierung daher auf, folgende Maßnahmen zu treffen: 1. Die Bundesregierung sorgt gegenüber den Bundesländern bis Ende März 2006 für eine Klarstellung in den vorläufigen Anwendungshinweisen des Bundesministeriums des Innern, die dem Ziel des Gesetzgebers entspricht. Hierin sind insbesondere die Zumutbarkeit einer Ausreise sowie die beson- dere Situation in Deutschland aufgewachsener Kinder und Jugendlicher zu berücksichtigen. 2. Die Bundesregierung legt dem Deutschen Bundestag zeitnah einen Gesetz- entwurf zur Änderung von § 25 Abs. 5 AufenthG vor, der der Intention des Gesetzgebers gerecht wird, wenn auf dem vorgenannten Weg keine Ände- rung der Praxis der Bundesländer zu erreichen ist. Berlin, den 15. Februar 2006 Renate Künast, Fritz Kuhn und Fraktion Begründung Der ehemalige Bundesminister des Innern, Otto Schily, hatte in der Debatte zur Verabschiedung des Zuwanderungsgesetzes vor dem Deutschen Bundestag er- -

Beschlussempfehlung Und Bericht Des Rechtsausschusses (6

Deutscher Bundestag Drucksache 14/8284 14. Wahlperiode 20. 02. 2002 Beschlussempfehlung und Bericht des Rechtsausschusses (6. Ausschuss) zu dem Antrag der Abgeordneten Wolfgang Bosbach, Norbert Geis, Erwin Marschewski (Recklinghausen), weiterer Abgeordneter und der Fraktion der CDU/CSU – Drucksache 14/6539 – Kriminalität wirksamer bekämpfen – Innere Sicherheit gewährleisten A. Problem Der Antrag geht davon aus, dass es sich bei Freiheit und Sicherheit um elemen- tare Grundbedürfnisse des Menschen handele. Aus dem hoheitlichen Anspruch des Staates auf das Gewaltmonopol resultiere seine Verpflichtung, Freiheit und innere Sicherheit zu gewährleisten. Im Rechtsstaat sei die innere Sicherheit Grundlage für Freiheit und Frieden nach innen. Der Schutz vor Kriminalität, die Verhinderung von Straftaten und ihre Aufklärung, die Ahndung von Verbre- chen sowie der Schutz vor den Gefahren für die öffentliche Sicherheit und Ord- nung seien unabdingbare Voraussetzung für die Lebensqualität der Bürger und ihr gedeihliches Zusammenleben. Nach Auffassung der Antragsteller sei die Sicherheit ein wichtiger Faktor nicht zuletzt auch für den Wirtschaftsstandort Deutschland. Die polizeiliche Kriminalstatistik für das Jahr 2000 habe belegt, dass ein wirklicher Durchbruch bei der Bekämpfung der Kriminalität bislang noch nicht gelungen sei, da die Kriminalitätszahlen insgesamt auf hohem Niveau stagnieren. Der Schutz der Bürger müsse Maßstab des Handelns sein. Die innere Sicherheit vertrage keine Experimente zu Lasten der Bevölkerung. Die Antragsteller fordern u. a. eine Bekämpfung der Kinder- und Jugendkrimi- nalität, der Rauschgiftkriminalität, der grenzüberschreitenden Kriminalität sowie des Extremismus und von Sexualstraftaten. B. Lösung Einstimmige Ablehnung des Antrags gegen die Stimmen der Fraktion der CDU/CSU C. Alternativen Keine D. Kosten Wurden im Ausschuss nicht erörtert. Drucksache 14/8284 – 2 – Deutscher Bundestag – 14. -

Kapitel 5.8 Arbeitskreise Und Arbeitsgruppen 29.05.2020

DHB Kapitel 5.8 Arbeitskreise und Arbeitsgruppen 29.05.2020 5.8 Arbeitskreise und Arbeitsgruppen Stand: 29.5.2020 Seit der 2. Wahlperiode (1953–1957) bilden die Fraktionen der CDU/CSU und SPD, seit der 3. Wahlperiode auch die FDP-Fraktion interne Arbeitskreise bzw. Arbeitsgruppen, deren Arbeitsgebiet bei der CDU/CSU-Fraktion zu Beginn der 9. Wahlperiode, bei der SPD- Fraktion während der 12. Wahlperiode der Gliederung der Bundestagsausschüsse entspricht. Die kleineren Fraktionen bzw. die Gruppen haben Arbeitsgruppen mit einem Arbeitsgebiet, das die Bereiche mehrerer Bundestagsausschüsse umfasst. Die Arbeitskreise und Arbeitsgruppen der Fraktionen sind Hilfsorgane der Fraktionsvollversammlung und dienen der fraktionsinternen Vorberatung. Arbeitsgruppen der CDU/CSU Vorsitzende der Arbeitsgruppen Wahl- (in der Regel zugleich Sprecher der Fraktionen für die einzelnen Fachgebiete) der periode CDU/CSU 12. WP 1. Recht (einschließlich Wahlprüfung, Immunität und Geschäftsordnung sowie 1990–1994 Petitionen) Norbert Geis (CSU) 2. Inneres und Sport Johannes Gerster (CDU) (bis 21.1.1992) Erwin Marschewski (CDU) (ab 21.1.1992) 3. Wirtschaft Matthias Wissmann (CDU) (bis 9.2.1993) Rainer Haungs (CDU) (ab 9.2.1993) 4. Ernährung, Landwirtschaft und Forsten Egon Susset (CDU) 5. Verkehr Dirk Fischer (CDU) 6. Post und Telekommunikation Gerhard O. Pfeffermann (CDU) (bis 6.9.1993) Elmar Müller (CDU) (ab 21.9.1993) 7. Raumordnung, Bauwesen und Städtebau Dietmar Kansy (CDU) 8. Finanzen Kurt Falthauser (CSU) (bis 9.2.1993) Hansgeorg Hauser (CSU) (ab 9.2.1993) 9. Haushalt Jochen Borchert (CDU) (bis 21.1.1993) Adolf Roth (CDU) (ab 9.2.1993) 10. Arbeit und Soziales Julius Louven (CDU) 11. Gesundheit Paul Hoffacker (CDU) Seite 1 von 34 DHB Kapitel 5.8 Arbeitskreise und Arbeitsgruppen 29.05.2020 Vorsitzende der Arbeitsgruppen Wahl- (in der Regel zugleich Sprecher der Fraktionen für die einzelnen Fachgebiete) der periode CDU/CSU 12. -

Alles Liebe, Oder Was?

Gesellschaft BAVARIA Brautleute bei traditioneller Hochzeitsfeier: „Unter dem besonderen Schutz der staatlichen Ordnung“ GLEICHBERECHTIGUNG Alles Liebe, oder was? Der Innenminister und die Justizministerin sind eigentlich dagegen, aber den Grünen ist es ein dringendes Anliegen: Dass Schwule und Lesben demnächst die Ehe eingehen dürfen, löst einen Kulturkampf aus. Die Traditionalisten drohen mit einer Verfassungsklage. ie umstürzlerische Geschichte ist Kinder ausüben. Einen „Schritt in die Otto Schily, der Bedenkenträger in der bis ins Detail geplant. Es soll ganz Degeneration“ nennt das Erzbischof SPD, sekundiert: Der Gesetzentwurf brin- Dharmlos anfangen. Johannes Dyba (siehe SPIEGEL-Streit- ge die schwulen Partnerschaften in eine „Der Standesbeamte soll die Lebens- gespräch Seite 86). verfassungsrechtlich problematische Kon- partner einzeln befragen, ob sie eine Le- Die endlich gefundene Rechtsform zur kurrenzsituation zur bürgerlichen Ehe. benspartnerschaft begründen wollen“, „Befreiung der Homosexuellen von ihrer Dem Kanzler ist das Vorhaben aus der heißt es in Paragraf 1. „Wenn die Lebens- Unterdrückung“ (der Grünen-Abgeordne- grünen Versuchsküche nicht pragmatisch partner diese Frage bejahen, soll der Stan- te und Gesetzesmitautor Volker Beck) ruft genug. Wenn man sich hier um Minder- desbeamte erklären, dass die Lebenspart- in der CSU Pläne für Unterschriften- heiten zerstreite, riskiere man die Kon- nerschaft nunmehr begründet ist.“ Dann sammlungen wie gegen die doppelte senspolitik, nörgelte er vor Genossen. darf das junge Paar -

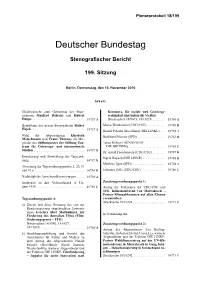

Plenarprotokoll 18/199

Plenarprotokoll 18/199 Deutscher Bundestag Stenografischer Bericht 199. Sitzung Berlin, Donnerstag, den 10. November 2016 Inhalt: Glückwünsche zum Geburtstag der Abge- Kommerz, für soziale und Genderge- ordneten Manfred Behrens und Hubert rechtigkeit und kulturelle Vielfalt Hüppe .............................. 19757 A Drucksachen 18/8073, 18/10218 ....... 19760 A Begrüßung des neuen Abgeordneten Rainer Marco Wanderwitz (CDU/CSU) .......... 19760 B Hajek .............................. 19757 A Harald Petzold (Havelland) (DIE LINKE) .. 19762 A Wahl der Abgeordneten Elisabeth Burkhard Blienert (SPD) ................ 19763 B Motschmann und Franz Thönnes als Mit- glieder des Stiftungsrates der Stiftung Zen- Tabea Rößner (BÜNDNIS 90/ trum für Osteuropa- und internationale DIE GRÜNEN) ..................... 19765 C Studien ............................. 19757 B Dr. Astrid Freudenstein (CDU/CSU) ...... 19767 B Erweiterung und Abwicklung der Tagesord- Sigrid Hupach (DIE LINKE) ............ 19768 B nung. 19757 B Matthias Ilgen (SPD) .................. 19769 A Absetzung der Tagesordnungspunkte 5, 20, 31 und 41 a ............................. 19758 D Johannes Selle (CDU/CSU) ............. 19769 C Nachträgliche Ausschussüberweisungen ... 19759 A Gedenken an den Volksaufstand in Un- Zusatztagesordnungspunkt 1: garn 1956 ........................... 19759 C Antrag der Fraktionen der CDU/CSU und SPD: Klimakonferenz von Marrakesch – Pariser Klimaabkommen auf allen Ebenen Tagesordnungspunkt 4: vorantreiben Drucksache 18/10238 .................. 19771 C a) -

Framing the Same-Sex Marriage Debate in the 17Th Session of the German Bundestag

University of Mississippi eGrove Honors College (Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors Theses Honors College) 2014 Ja, Ich Will: Framing the Same-Sex Marriage Debate in the 17th Session of the German Bundestag Stephen Colby Woods University of Mississippi. Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/hon_thesis Part of the Sociology Commons Recommended Citation Woods, Stephen Colby, "Ja, Ich Will: Framing the Same-Sex Marriage Debate in the 17th Session of the German Bundestag" (2014). Honors Theses. 875. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/hon_thesis/875 This Undergraduate Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College (Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College) at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. JA, ICH WILL: FRAMING THE SAME-SEX MARRIAGE DEBATE IN THE 17TH SESSION OF THE GERMAN BUNDESTAG 2014 By S. Colby Woods A thesis presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for completion Of the Bachelor of Arts degree in International Studies Croft Institute for International Studies Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College University of Mississippi University of Mississippi May 2014 Approved: __________________________ Advisor: Dr. Ross Haenfler __________________________ Reader: Dr. Kees Gispen __________________________ Reader: Dr. Alice Cooper © 2014 Stephen Colby Woods ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS AND DEDICATION I would first like to thank the Croft Institute for International Studies and the Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College for fostering my academic growth and development over the past four years. I want to express my sincerest gratitude to my thesis advisor, Dr.