THE PALACES of HOMER. IT Is Much to Be Regretted That

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ms. Legrange's Lesson Plans

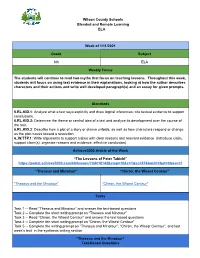

Wilson County Schools Blended and Remote Learning ELA Week of 1/11/2021 Grade Subject 6th ELA Weekly Focus The students will continue to read two myths that focus on teaching lessons. Throughout this week, students will focus on using text evidence in their explanations, looking at how the author describes characters and their actions and write well developed paragraph(s) and an essay for given prompts. Standards 6.RL.KID.1: Analyze what a text says explicitly and draw logical inferences; cite textual evidence to support conclusions. 6.RL.KID.2: Determine the theme or central idea of a text and analyze its development over the course of the text. 6.RL.KID.3: Describe how a plot of a story or drama unfolds, as well as how characters respond or change as the plot moves toward a resolution. 6..W.TTP.1 : Write arguments to support claims with clear reasons and relevant evidence (introduce claim, support claim(s), organize reasons and evidence, effective conclusion). Achieve3000 Article of the Week “The Lessons of Peter Tabichi” https://portal.achieve3000.com/kb/lesson/?lid=18142&step=10&c=1&sc=276&oid=0&ot=0&asn=1 “Theseus and Minotaur” “Chiron, the Wisest Centaur” "Theseus and the Minotaur" "Chiron, the Wisest Centaur" Tasks Task 1 -- Read “Theseus and Minotaur” and answer the text-based questions Task 2 -- Complete the short writing prompt on “Theseus and Minotaur” Task 3 -- Read ”Chiron, the Wisest Centaur” and answer the text-based questions Task 4 -- Complete the short writing prompt on “Chiron, the Wisest Centaur” Task 5 -- Complete the writing prompt on “Theseus and Minotaur”, “Chiron, the Wisest Centaur”, and last week’s text in the synthesis writing section. -

1 Divine Intervention and Disguise in Homer's Iliad Senior Thesis

Divine Intervention and Disguise in Homer’s Iliad Senior Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Undergraduate School of Arts and Sciences Brandeis University Undergraduate Program in Classical Studies Professor Joel Christensen, Advisor In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts By Joana Jankulla May 2018 Copyright by Joana Jankulla 1 Copyright by Joana Jankulla © 2018 2 Acknowledgements First and foremost, I would like to thank my advisor, Professor Joel Christensen. Thank you, Professor Christensen for guiding me through this process, expressing confidence in me, and being available whenever I had any questions or concerns. I would not have been able to complete this work without you. Secondly, I would like to thank Professor Ann Olga Koloski-Ostrow and Professor Cheryl Walker for reading my thesis and providing me with feedback. The Classics Department at Brandeis University has been an instrumental part of my growth in my four years as an undergraduate, and I am eternally thankful to all the professors and staff members in the department. Thank you to my friends, specifically Erica Theroux, Sarah Jousset, Anna Craven, Rachel Goldstein, Taylor McKinnon and Georgie Contreras for providing me with a lot of emotional support this year. I hope you all know how grateful I am for you as friends and how much I have appreciated your love this year. Thank you to my mom for FaceTiming me every time I was stressed about completing my thesis and encouraging me every step of the way. Finally, thank you to Ian Leeds for dropping everything and coming to me each time I needed it. -

Phoenix in the Iliad

University of Mary Washington Eagle Scholar Student Research Submissions Spring 5-4-2017 Phoenix in the Iliad Kati M. Justice Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.umw.edu/student_research Part of the Classics Commons Recommended Citation Justice, Kati M., "Phoenix in the Iliad" (2017). Student Research Submissions. 152. https://scholar.umw.edu/student_research/152 This Honors Project is brought to you for free and open access by Eagle Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Research Submissions by an authorized administrator of Eagle Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PHOENIX IN THE ILIAD An honors paper submitted to the Department of Classics, Philosophy, and Religion of the University of Mary Washington in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Departmental Honors Kati M. Justice May 2017 By signing your name below, you affirm that this work is the complete and final version of your paper submitted in partial fulfillment of a degree from the University of Mary Washington. You affirm the University of Mary Washington honor pledge: "I hereby declare upon my word of honor that I have neither given nor received unauthorized help on this work." Kati Justice 05/04/17 (digital signature) PHOENIX IN THE ILIAD Kati Justice Dr. Angela Pitts CLAS 485 April 24, 2017 2 Abstract This paper analyzes evidence to support the claim that Phoenix is an narratologically central and original Homeric character in the Iliad. Phoenix, the instructor of Achilles, tries to persuade Achilles to protect the ships of Achaeans during his speech. At the end of his speech, Phoenix tells Achilles about the story of Meleager which serves as a warning about waiting too long to fight the Trojans. -

The Arms of Achilles: Re-Exchange in the Iliad

The Arms of Achilles: Re-Exchange in the Iliad by Eirene Seiradaki A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of Classics University of Toronto © Copyright by Eirene Seiradaki (2014) “The Arms of Achilles: Re-Exchange in the Iliad ” Eirene Seiradaki Doctor of Philosophy Department of Classics University of Toronto 2014 Abstract This dissertation offers an interpretation of the re-exchange of the first set of Achilles’ arms in the Iliad by gift, loan, capture, and re-capture. Each transfer of the arms is examined in relation to the poem’s dramatic action, characterisation, and representation of social institutions and ethical values. Modern anthropological and economic approaches are employed in order to elucidate standard elements surrounding certain types of exchange. Nevertheless, the study primarily involves textual analysis of the Iliadic narratives recounting the circulation-process of Achilles’ arms, with frequent reference to the general context of Homeric exchange and re-exchange. The origin of the armour as a wedding gift to Peleus for his marriage to Thetis and its consequent bequest to Achilles signifies it as the hero’s inalienable possession and marks it as the symbol of his fate in the Iliad . Similarly to the armour, the spear, a gift of Cheiron to Peleus, is later inherited by his son. Achilles’ own bond to Cheiron makes this weapon another inalienable possession of the hero. As the centaur’s legacy to his pupil, the spear symbolises Achilles’ awareness of his coming death. In the present time of the Iliad , ii Achilles lends his armour to Patroclus under conditions that indicate his continuing ownership over his panoply and ensure the safe use of the divine weapons by his friend. -

Euripides and Gender: the Difference the Fragments Make

Euripides and Gender: The Difference the Fragments Make Melissa Karen Anne Funke A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2013 Reading Committee: Ruby Blondell, Chair Deborah Kamen Olga Levaniouk Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Classics © Copyright 2013 Melissa Karen Anne Funke University of Washington Abstract Euripides and Gender: The Difference the Fragments Make Melissa Karen Anne Funke Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor Ruby Blondell Department of Classics Research on gender in Greek tragedy has traditionally focused on the extant plays, with only sporadic recourse to discussion of the many fragmentary plays for which we have evidence. This project aims to perform an extensive study of the sixty-two fragmentary plays of Euripides in order to provide a picture of his presentation of gender that is as full as possible. Beginning with an overview of the history of the collection and transmission of the fragments and an introduction to the study of gender in tragedy and Euripides’ extant plays, this project takes up the contexts in which the fragments are found and the supplementary information on plot and character (known as testimonia) as a guide in its analysis of the fragments themselves. These contexts include the fifth- century CE anthology of Stobaeus, who preserved over one third of Euripides’ fragments, and other late antique sources such as Clement’s Miscellanies, Plutarch’s Moralia, and Athenaeus’ Deipnosophistae. The sections on testimonia investigate sources ranging from the mythographers Hyginus and Apollodorus to Apulian pottery to a group of papyrus hypotheses known as the “Tales from Euripides”, with a special focus on plot-type, especially the rape-and-recognition and Potiphar’s wife storylines. -

I I I: Briseis. to Achilles

I I I: Briseis. to Achilles The character of Briseis is derived by Ovid from the Iliad. In that soQrce, however, the character of Briseis is scarcely developed and she is little more than a pivot around which the fabled wrath of Achilles is devdpped. While she may have been loved by Achilles in Homer's account, we should also note that for him the loss ofBriseis must surely have been perceived as an insult of the. gravest propor tions. We know very litde about Briseis and the charms she might have had in the eyes of Achilles; we only know that upon losing her Achilles retired from combat to his tent. In the Heroides, Briseis becomes a woman richly endowed with human feeling who grieves that she has not been reunited with the man she. loves, who fears that she will be supplanted by another, and who must now find her future life with those who destroyed her homeland, her family and her heritage. For Briseis the attraction identified u love is dangerously close to the fear of abandonment. She does not object so much to captivity as to the uncer~ty and instability that it has brought into her life. In this, Briseis echoes a theme which permeates the Heroidts: the lover and the beloved both seek to bring into their .lives a degree of permanence and changelessness that in reality is nearly impossible of attainment. But the situation of Bri~eis is still more tenuous. She is not only a pawn in a mysterious game being played out by characters superior to her in every way but she is also a barbarian. -

Greek Mythology / Apollodorus; Translated by Robin Hard

Great Clarendon Street, Oxford 0X2 6DP Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide in Oxford New York Athens Auckland Bangkok Bogotá Buenos Aires Calcutta Cape Town Chennai Dar es Salaam Delhi Florence Hong Kong Istanbul Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Mumbai Nairobi Paris São Paulo Shanghai Singapore Taipei Tokyo Toronto Warsaw with associated companies in Berlin Ibadan Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries Published in the United States by Oxford University Press Inc., New York © Robin Hard 1997 The moral rights of the author have been asserted Database right Oxford University Press (maker) First published as a World’s Classics paperback 1997 Reissued as an Oxford World’s Classics paperback 1998 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organizations. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above You must not circulate this book in any other binding or cover and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Apollodorus. [Bibliotheca. English] The library of Greek mythology / Apollodorus; translated by Robin Hard. -

Becoming Macedonian: Name Mapping and Ethnic Identity. the Case of Hephaistion*

Karanos 3, 2020 11-37 Becoming Macedonian: Name Mapping and Ethnic Identity. The Case of Hephaistion* by Jeanne Reames University of Nebraska at Omaha [email protected] With the Digital Assistance of Jason Heppler and Cory Starman ABSTRACT An epigraphical survey (with digital mapping component) of Greece and Magna Graecia reveals a pattern as to where Hephais-based names appear, up through the second century BCE. Spelled with an /eta/, these names are almost exclusively Attic-Ionian, while Haphēs-based names, spelled with an alpha, are Doric-Aeolian, and much fewer in number. There is virtually no overlap, except at the Panhellenic site of Delphi, and in a few colonies around the Black Sea. Furthermore, cult for the god Hephaistos –long recognized as a non-Greek borrowing– was popular primarily in Attic-Ionian and “Pelasgian” regions, precisely the same areas where we find Hephais-root names. The only area where Haphēs-based names appear in any quantity, Boeotia, also had an important cult related to the god. Otherwise, Hephaistos was not a terribly important deity in Doric-Aeolian populations. This epigraphic (and religious) record calls into question the assumed Macedonian ethnicity of the king’s best friend and alter-ego, Hephaistion. According to Tataki, Macedonian naming patterns followed distinctively non-Attic patterns, and cult for the god Hephaistos is absent in Macedonia (outside Samothrace). A recently published 4th century curse tablet from Pydna could, however, provide a clue as to why a Macedonian Companion had such a uniquely Attic-Ionian name. If Hephaistion’s ancestry was not, in fact, ethnically Macedonian, this may offer us an interesting insight into fluidity of Macedonian identity under the monarchy, and thereby, to ancient conceptualizations of ethnicity more broadly. -

UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Listening for the Plot: The Role of Desire in the Iliad's Narrative Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5mk193gc Author Lesser, Rachel Hart Publication Date 2015 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Listening for the Plot The Role of Desire in the Iliad’s Narrative By Rachel Hart Lesser A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Classics and the Designated Emphasis in Women, Gender and Sexuality in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in Charge: Professor Mark Griffith, Chair Professor Leslie Kurke Professor Richard P. Martin Professor Andrew Stewart Professor James G. Turner Spring 2015 © Copyright by Rachel Hart Lesser, 2015. All rights reserved. 1 ABSTRACT Listening for the Plot: The Role of Desire in the Iliad’s Narrative by Rachel Hart Lesser Doctor of Philosophy in Classics and the Designated Emphasis in Women, Gender and Sexuality University of California, Berkeley Professor Mark Griffith, Chair This dissertation is the first study to identify desire as a fundamental dynamic in the Iliad that structures its narrative and audience reception. Building on Peter Brooks’ concept of “narrative erotics,” I show how the desires of Akhilleus and his counterpart Helen drive and shape the Iliad’s plot and how Homer captures and maintains the audience’s attention by activating its parallel “narrative desire” to plot out the Iliad’s unique treatment of the Trojan War story. I argue that Homer encodes the characters’ desires in repeated triangles of subject, object, and rival, and that Akhilleus’ aggressive desires to dominate his rivals Agamemnon and Hektor cause the heroism and suffering at the poem’s heart. -

Sing, Goddess, Sing of the Rage of Achilles, Son of Peleus—

Homer, Iliad Excerpts 1 HOMER, ILIAD TRANSLATION BY IAN JOHNSTON Dr. D’s note: These are excerpts from the complete text of Johnston’s translation, available here. The full site shows original line numbers, and has some explanatory notes, and you should use it if you use this material for one of your written topics. Book I: The quarrel between Achilles and Agamemnon begins The Greeks have been waging war against Troy and its allies for 10 years, and in raids against smaller allies, have already won war prizes including women like Chryseis and Achilles’ girl, Briseis. Sing, Goddess, sing of the rage of Achilles, son of Peleus— that murderous anger which condemned Achaeans to countless agonies and threw many warrior souls deep into Hades, leaving their dead bodies carrion food for dogs and birds— all in fulfilment of the will of Zeus. Start at the point where Agamemnon, son of Atreus, that king of men, quarrelled with noble Achilles. Which of the gods incited these two men to fight? That god was Apollo, son of Zeus and Leto. Angry with Agamemnon, he cast plague down onto the troops—deadly infectious evil. For Agamemnon had dishonoured the god’s priest, Chryses, who’d come to the ships to find his daughter, Chryseis, bringing with him a huge ransom. In his hand he held up on a golden staff the scarf sacred to archer god Apollo. He begged Achaeans, above all the army’s leaders, the two sons of Atreus: “Menelaus, Agamemnon, sons of Atreus, all you well-armed Achaeans, may the gods on Olympus grant you wipe out Priam’s city, and then return home safe and sound. -

The Iliad of Homer by Homer

The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Iliad of Homer by Homer This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at http://www.gutenberg.org/license Title: The Iliad of Homer Author: Homer Release Date: September 2006 [Ebook 6130] Language: English ***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE ILIAD OF HOMER*** The Iliad of Homer Translated by Alexander Pope, with notes by the Rev. Theodore Alois Buckley, M.A., F.S.A. and Flaxman's Designs. 1899 Contents INTRODUCTION. ix POPE'S PREFACE TO THE ILIAD OF HOMER . xlv BOOK I. .3 BOOK II. 41 BOOK III. 85 BOOK IV. 111 BOOK V. 137 BOOK VI. 181 BOOK VII. 209 BOOK VIII. 233 BOOK IX. 261 BOOK X. 295 BOOK XI. 319 BOOK XII. 355 BOOK XIII. 377 BOOK XIV. 415 BOOK XV. 441 BOOK XVI. 473 BOOK XVII. 513 BOOK XVIII. 545 BOOK XIX. 575 BOOK XX. 593 BOOK XXI. 615 BOOK XXII. 641 BOOK XXIII. 667 BOOK XXIV. 707 CONCLUDING NOTE. 747 Illustrations HOMER INVOKING THE MUSE. .6 MARS. 13 MINERVA REPRESSING THE FURY OF ACHILLES. 16 THE DEPARTURE OF BRISEIS FROM THE TENT OF ACHILLES. 23 THETIS CALLING BRIAREUS TO THE ASSISTANCE OF JUPITER. 27 THETIS ENTREATING JUPITER TO HONOUR ACHILLES. 32 VULCAN. 35 JUPITER. 38 THE APOTHEOSIS OF HOMER. 39 JUPITER SENDING THE EVIL DREAM TO AGAMEMNON. 43 NEPTUNE. 66 VENUS, DISGUISED, INVITING HELEN TO THE CHAMBER OF PARIS. -

Wilson County Schools Blended and Remote Learning Wilkins ELA 6Th Grade

Wilson County Schools Blended and Remote Learning Wilkins ELA 6th Grade Week of 1/11/2021 Grade Subject 6th ELA Weekly Focus The students will continue to read two myths that focus on teaching lessons. Throughout this week, students will focus on using text evidence in their explanations, looking at how the author describes characters and their actions and write well developed paragraph(s) and an essay for given prompts. Standards 6.RL.KID.1: Analyze what a text says explicitly and draw logical inferences; cite textual evidence to support conclusions. 6.RL.KID.2: Determine the theme or central idea of a text and analyze its development over the course of the text. 6.RL.KID.3: Describe how a plot of a story or drama unfolds, as well as how characters respond or change as the plot moves toward a resolution. 6..W.TTP.1: Write arguments to support claims with clear reasons and relevant evidence (introduce claim, support claim(s), organize reasons and evidence, effective conclusion). Achieve3000 Article of the Week 3rd Block completes on Tuesday 1/9, 2nd, 4th, 6th on Wednesday 1/10 “The Lessons of Peter Tabichi” https://portal.achieve3000.com/kb/lesson/?lid=18142&step=10&c=1&sc=276&oid=0&ot=0&asn=1 “Theseus and Minotaur” “Chiron, the Wisest Centaur” (found on commonlit.org) (found on commonlit.org) "Theseus and the Minotaur" "Chiron, the Wisest Centaur" Tasks Task 1 -- Read “Theseus and Minotaur” and answer the text-based questions Task 2 -- Complete the short writing prompt on “Theseus and Minotaur” Task 3 -- Read ”Chiron, the Wisest Centaur” and answer the text-based questions Task 4 -- Complete the short writing prompt on “Chiron, the Wisest Centaur” Task 5 -- Complete the writing prompt on “Theseus and Minotaur”, “Chiron, the Wisest Centaur”, and last Wilson County Schools Blended and Remote Learning Wilkins ELA 6th Grade week’s text in the synthesis writing section.