1 Divine Intervention and Disguise in Homer's Iliad Senior Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Warrior Vaunts in the Iliad

250 Poulheria Kyriakou die bloße Rachehandlung ihm keine Befriedigung schaffen kann. Ihm fehlt die Erkenntnis der Beschaffenheit des Menschlichen, die größere Dauer und höheren Wert besitzt, als die bloße Rache- handlung. Es ist bezeichnend, daß Achilleus diese Wende nicht selbst durchführen kann, sondern daß sein Entschluß wieder als Ausfluß des göttlichen Willens dargeboten wird, wodurch der Weg zu einer echten Versöhnung geöffnet wird. Achilleus erfährt jetzt, was es heißt, hilfreich und edel zu handeln, nicht aber den Stolz auf die rein körperliche Gewalt als letztes Ziel ritterlichen Daseins an- zusehen. Es kann kein Zufall sein, daß die Ilias mit der feierlichen Beisetzung Hektors schließt, genau mit dem Akt, den Achilleus selbst vor dem Zweikampf höhnisch abgewiesen hatte. Es gibt also auch für das heroische Dasein eine Art der Auseinandersetzung, die das gemeinsame höhere Recht in Geltung läßt. Wollte Homer darauf hinweisen, daß er diese Art des Rittertums für die richtige hält? Bonn Hartmut Erbse WARRIOR VAUNTS IN THE ILIAD Warrior vaunts, the short speeches of triumph delivered over a vanquished dead or dying opponent, are peculiar to the Iliad and very rare in extant literature after Homer.1 These speeches have 1) In Od. 22 only the cowherd Philoetius vaunts over the suitor Ctesippus (287–91), ‘admonishing’ him not to boast in the future but to let the gods be the arbiters of his claims. A more conventional vaunt but over an unconventional ene- my is found in the Homeric Hymn to Apollo (362–70), on which see the detailed discussion of A.M. Miller, From Delos to Delphi (Leiden 1986) 88–91. -

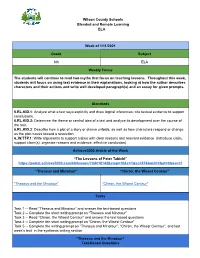

Ms. Legrange's Lesson Plans

Wilson County Schools Blended and Remote Learning ELA Week of 1/11/2021 Grade Subject 6th ELA Weekly Focus The students will continue to read two myths that focus on teaching lessons. Throughout this week, students will focus on using text evidence in their explanations, looking at how the author describes characters and their actions and write well developed paragraph(s) and an essay for given prompts. Standards 6.RL.KID.1: Analyze what a text says explicitly and draw logical inferences; cite textual evidence to support conclusions. 6.RL.KID.2: Determine the theme or central idea of a text and analyze its development over the course of the text. 6.RL.KID.3: Describe how a plot of a story or drama unfolds, as well as how characters respond or change as the plot moves toward a resolution. 6..W.TTP.1 : Write arguments to support claims with clear reasons and relevant evidence (introduce claim, support claim(s), organize reasons and evidence, effective conclusion). Achieve3000 Article of the Week “The Lessons of Peter Tabichi” https://portal.achieve3000.com/kb/lesson/?lid=18142&step=10&c=1&sc=276&oid=0&ot=0&asn=1 “Theseus and Minotaur” “Chiron, the Wisest Centaur” "Theseus and the Minotaur" "Chiron, the Wisest Centaur" Tasks Task 1 -- Read “Theseus and Minotaur” and answer the text-based questions Task 2 -- Complete the short writing prompt on “Theseus and Minotaur” Task 3 -- Read ”Chiron, the Wisest Centaur” and answer the text-based questions Task 4 -- Complete the short writing prompt on “Chiron, the Wisest Centaur” Task 5 -- Complete the writing prompt on “Theseus and Minotaur”, “Chiron, the Wisest Centaur”, and last week’s text in the synthesis writing section. -

Aeneidic and Odyssean Patterns of Escape and Release in Tolkien's "The Fall of Gondolin" and the Return of the King

Volume 18 Number 2 Article 1 Spring 4-15-1992 Aeneidic and Odyssean Patterns of Escape and Release in Tolkien's "The Fall of Gondolin" and The Return of the King David Greenman Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons Recommended Citation Greenman, David (1992) "Aeneidic and Odyssean Patterns of Escape and Release in Tolkien's "The Fall of Gondolin" and The Return of the King," Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature: Vol. 18 : No. 2 , Article 1. Available at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore/vol18/iss2/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Mythopoeic Society at SWOSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature by an authorized editor of SWOSU Digital Commons. An ADA compliant document is available upon request. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To join the Mythopoeic Society go to: http://www.mythsoc.org/join.htm Mythcon 51: A VIRTUAL “HALFLING” MYTHCON July 31 - August 1, 2021 (Saturday and Sunday) http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-51.htm Mythcon 52: The Mythic, the Fantastic, and the Alien Albuquerque, New Mexico; July 29 - August 1, 2022 http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-52.htm Abstract Sees classical influence in the quest patterns of olkienT ’s heroes. Tuor fits the pattern of Aeneas (the Escape Quest) and the hobbits in Return of the King follow that of Odysseus (the Return Quest). -

Homer and Greek Epic

HomerHomer andand GreekGreek EpicEpic INTRODUCTION TO HOMERIC EPIC (CHAPTER 4.IV) • The Iliad, Books 23-24 • Overview of The Iliad, Books 23-24 • Analysis of Book 24: The Death-Journey of Priam •Grammar 4: Review of Parts of Speech: Nouns, Verbs, Adjectives, Adverbs, Pronouns, Prepositions and Conjunctions HomerHomer andand GreekGreek EpicEpic INTRODUCTION TO HOMERIC EPIC (CHAPTER 4.IV) Overview of The Iliad, Book 23 • Achilles holds funeral games in honor of Patroclus • these games serve to reunite the Greeks and restore their sense of camaraderie • but the Greeks and Trojans are still at odds • Achilles still refuses to return Hector’s corpse to his family HomerHomer andand GreekGreek EpicEpic INTRODUCTION TO HOMERIC EPIC (CHAPTER 4.IV) Overview of The Iliad, Book 24 • Achilles’ anger is as yet unresolved • the gods decide he must return Hector’s body • Zeus sends Thetis to tell him to inform him of their decision • she finds Achilles sulking in his tent and he agrees to accept ransom for Hector’s body HomerHomer andand GreekGreek EpicEpic INTRODUCTION TO HOMERIC EPIC (CHAPTER 4.IV) Overview of The Iliad, Book 24 • the gods also send a messenger to Priam and tell him to take many expensive goods to Achilles as a ransom for Hector’s body • he sneaks into the Greek camp and meets with Achilles • Achilles accepts Priam’s offer of ransom and gives him Hector’s body HomerHomer andand GreekGreek EpicEpic INTRODUCTION TO HOMERIC EPIC (CHAPTER 4.IV) Overview of The Iliad, Book 24 • Achilles and Priam arrange an eleven-day moratorium on fighting -

Let's Think About This Reasonably: the Conflict of Passion and Reason

Let’s Think About This Reasonably: The Conflict of Passion and Reason in Virgil’s The Aeneid Scott Kleinpeter Course: English 121 Honors Instructor: Joan Faust Essay Type: Poetry Analysis It has long been a philosophical debate as to which is more important in human nature: the ability to feel or the ability to reason. Both functions are integral in our composition as balanced beings, but throughout history, some cultures have invested more importance in one than the other. Ancient Rome, being heavily influenced by stoicism, is probably the earliest example of a society based fundamentally on reason. Its most esteemed leaders and statesmen such as Cicero and Marcus Aurelius are widely praised today for their acumen in affairs of state and personal ethics which has survived as part of the classical canon. But when mentioning the classical canon, and the argument that reason is essential to civilization, a reader need not look further than Virgil’s The Aeneid for a more relevant text. The Aeneid’s protagonist, Aeneas, is a pious man who relies on reason instead of passion to see him through adversities and whose actions are foiled by a cast of overly passionate characters. Personages such as Dido and Juno are both portrayed as emotionally-laden characters whose will is undermined by their more rational counterparts. Also, reason’s importance is expressed in a different way in Book VI when Aeneas’s father explains the role reason will play in the future Roman Empire. Because The Aeneid’s antagonists are capricious individuals who either die or never find contentment, the text very clearly shows the necessity of reason as a human trait for survival and as a means to discover lasting happiness. -

The Eternal Fire of Vesta

2016 Ian McElroy All Rights Reserved THE ETERNAL FIRE OF VESTA Roman Cultural Identity and the Legitimacy of Augustus By Ian McElroy A thesis submitted to the Graduate School-New Brunswick Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Master of Arts Graduate Program in Classics Written under the direction of Dr. Serena Connolly And approved by ___________________________________________ ___________________________________________ ___________________________________________ New Brunswick, New Jersey October 2016 ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS The Eternal Fire of Vesta: Roman Cultural Identity and the Legitimacy of Augustus By Ian McElroy Thesis Director: Dr. Serena Connolly Vesta and the Vestal Virgins represented the very core of Roman cultural identity, and Augustus positioned his public image beside them to augment his political legitimacy. Through analysis of material culture, historiography, and poetry that originated during the principate of Augustus, it becomes clear that each of these sources of evidence contributes to the public image projected by the leader whom Ronald Syme considered to be the first Roman emperor. The Ara Pacis Augustae and the Res Gestae Divi Augustae embody the legacy the Emperor wished to establish, and each of these cultural works contain significant references to the Vestal Virgins. The study of history Livy undertook also emphasized the pathetic plight of Rhea Silvia as she was compelled to become a Vestal. Livy and his contemporary Dionysius of Halicarnassus explored the foundation of the Vestal Order and each writer had his own explanation about how Numa founded it. The Roman poets Virgil, Horace, Ovid, and Tibullus incorporated Vesta and the Vestals into their work in a way that offers further proof of the way Augustus insinuated himself into the fabric of Roman cultural identity by associating his public image with these honored priestesses. -

Astrocladistics of the Jovian Trojan Swarms

MNRAS 000,1–26 (2020) Preprint 23 March 2021 Compiled using MNRAS LATEX style file v3.0 Astrocladistics of the Jovian Trojan Swarms Timothy R. Holt,1,2¢ Jonathan Horner,1 David Nesvorný,2 Rachel King,1 Marcel Popescu,3 Brad D. Carter,1 and Christopher C. E. Tylor,1 1Centre for Astrophysics, University of Southern Queensland, Toowoomba, QLD, Australia 2Department of Space Studies, Southwest Research Institute, Boulder, CO. USA. 3Astronomical Institute of the Romanian Academy, Bucharest, Romania. Accepted XXX. Received YYY; in original form ZZZ ABSTRACT The Jovian Trojans are two swarms of small objects that share Jupiter’s orbit, clustered around the leading and trailing Lagrange points, L4 and L5. In this work, we investigate the Jovian Trojan population using the technique of astrocladistics, an adaptation of the ‘tree of life’ approach used in biology. We combine colour data from WISE, SDSS, Gaia DR2 and MOVIS surveys with knowledge of the physical and orbital characteristics of the Trojans, to generate a classification tree composed of clans with distinctive characteristics. We identify 48 clans, indicating groups of objects that possibly share a common origin. Amongst these are several that contain members of the known collisional families, though our work identifies subtleties in that classification that bear future investigation. Our clans are often broken into subclans, and most can be grouped into 10 superclans, reflecting the hierarchical nature of the population. Outcomes from this project include the identification of several high priority objects for additional observations and as well as providing context for the objects to be visited by the forthcoming Lucy mission. -

Study Questions Helen of Troycomp

Study Questions Helen of Troy 1. What does Paris say about Agamemnon? That he treated Helen as a slave and he would have attacked Troy anyway. 2. What is Priam’s reaction to Paris’ action? What is Paris’ response? Priam is initially very upset with his son. Paris tries to defend himself and convince his father that he should allow Helen to stay because of her poor treatment. 3. What does Cassandra say when she first sees Helen? What warning does she give? Cassandra identifies Helen as a Spartan and says she does not belong there. Cassandra warns that Helen will bring about the end of Troy. 4. What does Helen say she wants to do? Why do you think she does this? She says she wants to return to her husband. She is probably doing this in an attempt to save lives. 5. What does Menelaus ask of King Priam? Who goes with him? Menelaus asks for his wife back. Odysseus goes with him. 6. How does Odysseus’ approach to Priam differ from Menelaus’? Who seems to be more successful? Odysseus reasons with Priam and tries to appeal to his sense of propriety; Menelaus simply threatened. Odysseus seems to be more successful; Priam actually considers his offer. 7. Why does Priam decide against returning Helen? What offer does he make to her? He finds out that Agamemnon sacrificed his daughter for safe passage to Troy; Agamemnon does not believe that is an action suited to a king. Priam offers Helen the opportunity to become Helen of Troy. 8. What do Agamemnon and Achilles do as the rest of the Greek army lands on the Trojan coast? They disguise themselves and sneak into the city. -

Metempsychosis in Aeneid Six Author(S): E

Metempsychosis in Aeneid Six Author(s): E. L. Harrison Reviewed work(s): Source: The Classical Journal, Vol. 73, No. 3 (Feb. - Mar., 1978), pp. 193-197 Published by: The Classical Association of the Middle West and South Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3296685 . Accessed: 12/02/2013 21:07 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The Classical Association of the Middle West and South is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Classical Journal. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded on Tue, 12 Feb 2013 21:07:57 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions METEMPSYCHOSISIN AENEID SIX The purposeof this note is to suggest that, in orderto understandmore clearly the lines in which Virgil preparesthe way for his paradeof heroes in Book Six (679-755), we need to appreciatethe difficulties presentedby the introduction of such an episode, and consider how he handled them.' Although we can only surmise, it seems highly probablethat, influencedby the practice at the funerals of prominentRomans of having relatives walk in processionwearing portrait-masks of the dead man's ancestors,2Virgil decided to stage a similar spectacle on a granderscale, including in its scope the great figures of Rome's past. -

Nick Susa Epic Mythomemology – the Iliad Book 1: Achilles Was Fighting

Nick Susa Epic Mythomemology – The Iliad Book 1: Achilles was fighting alongside Agamemnon, the King of Argos, during the Trojan war. After winning a battle each was given a war prize, a woman. Achilles was given Briseis, and Agamemnon was given Chryseis. However, the father of Chryseis, Chryses, who was also a priest of Apollo, wasn’t ready to part with his daughter and came with a ransom for his daughter for King Agamemnon. Agamemnon refused the ransom in favor of keeping Chryseis and threatened the priest. Horrified and upset the priest (Chryses) calls upon Apollo and asks him to put a plague upon the Achaean armies, one of which Agamemnon leads. For nine days the armies were struck with a plague, on the tenth Achilles called a meeting to find the reason for the plague. Calchas, a prophet and follower of Apollo, being protected by Achilles, explains that Agamemnon refusing the ransom was the reason for the plague and he must return the girl and make a sacrifice of one hundred cows to Apollo in order to end the plague. Agamemnon decides to appease Apollo, but only if he can take away Achilles war prize, Briseis. Achilles doesn’t believe that Agamemnon should gain Briseis, so the two begin to argue. Achilles decides that he and his men shall not fight in the war because of Agamemnon’s actions. After Agamemnon takes Briseis away, Achilles cries and prays to his mother, Thetis, asking her to have Zeus grant the Achaean armies many loses. Zeus was not around to be asked though, but after twelve days, he returns and promises to Thetis that he will grant the Trojans many victories and the Achaeans many losses. -

WRATH of ACHILLES: the MYTHS of the TROJAN WAR “The Feast of Peleus”

SING, GODDESS OF THE WRATH OF ACHILLES: THE MYTHS OF THE TROJAN WAR “The Feast Of Peleus” E. Burne-Jones (1872-81) Eris The Greek Goddess of Chaos Paris and the nymph Oinone happy on Mt. Ida Peter Paul Rubens, “Judgment Of Paris” Salvador Dali, “The Judgment of Paris” (1960-64) “Paris and Helen,” Jacques-Louis David (1788) “The Abduction of Helen” From an illuminated edition of Ovid’s Metamorphosis (late 15th c.) OATH OF TYNDAREUS When Helen reached marriageable age, the greatest kings and warriors from all Greece sought to win her hand. They brought magnificent gifts to her mortal father Tyndareus. The suitors included Ajax, Peleus, Diomedes, Patroclus and Odysseus. In return for Tyndareus’ niece Penelope in marriage, Odysseus drew up an oath to be taken by all the suitors. They would swear to accept the choice of Tyndareus. If any man ever took Helen by force, they would fight to regain her for her lawful husband. Tyndareus selected Menelaus, king of Sparta, who had brought the most valuable gifts. “Odysseus’ Induction,” Heywood Hardy (1874) “Thetis Dips Achilles Into The River Syx” Antoine Borel (18th c.) Achilles taught to play the lyre by Chiron Jan de Bray, “The Discovery of Achilles Among the Daughters of Lycomedes” [1664] Aulis today Achilles wounds Telephus in Mysia Iphigenia, Achilles, Clytemnestra and Agamemnon at Aulis “Sacrifice of Iphigenia at Aulis,” A wall painting from the House of the Tragic Poet at Pompeii 63-70 CE Peter Pietersz Lastman, “Orestes and Pylades Disputing the Altar” (1614) Philoctetes with Heracles’ bow on Lemnos Protesilaus steps ashore at Troy Patroclus separates Briseis from Achilles Briseis and Agamemnon Jean-Auguste Dominique Ingres, “Jupiter and Thetis” (1811) Paris and Menelaus in single combat Aeneas and Aphrodite were both wounded by Diomedes “Achilles Receives Agamemnon’s Messengers,” Jacques-Louis David (1801) “Helen on the Walls of Troy,” -Gustave Moreau, c. -

(2018). Gazing at Helen with Stesichorus. in A. Kampakoglou, & A

Finglass, P. J. (2018). Gazing at Helen with Stesichorus. In A. Kampakoglou, & A. Novokhatko (Eds.), Gaze, Vision, and Visuality in Ancient Greek Literature (pp. 140–159). (Trends in Classics Supplements; Vol. 54). Walter de Gruyter GmbH. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110571288-007 Peer reviewed version License (if available): CC BY-NC-ND Link to published version (if available): 10.1515/9783110571288-007 Link to publication record in Explore Bristol Research PDF-document This is the accepted author manuscript (AAM). The final published version (version of record) is available online via De Gruyter at DOI 10.1515/9783110571288-007. Please refer to any applicable terms of use of the publisher. University of Bristol - Explore Bristol Research General rights This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite only the published version using the reference above. Full terms of use are available: http://www.bristol.ac.uk/red/research-policy/pure/user-guides/ebr-terms/ GAZING AT HELEN WITH STESICHORUS P. J. Finglass οἳ δ’ ὡς οὖν εἴδονθ’ Ἑλένην ἐπὶ πύργον ἰοῦσαν, 155 ἦκα πρὸς ἀλλήλους ἔπεα πτερόεντ’ ἀγόρευον· οὐ νέμεσις Τρῶας καὶ ἐϋκνήμιδας Ἀχαιοὺς τοιῆιδ’ ἀμφὶ γυναικὶ πολὺν χρόνον ἄλγεα πάσχειν· αἰνῶς ἀθανάτηισι θεῆις εἰς ὦπα ἔοικεν· ἀλλὰ καὶ ὧς τοίη περ ἐοῦσ’ ἐν νηυσὶ νεέσθω, 160 μηδ’ ἡμῖν τεκέεσσί τ’ ὀπίσσω πῆμα λίποιτο. Hom. Il. 3.154-60 When they saw Helen on her way to the tower, they began to speak winged words quietly to each other. ‘It is no cause for anger that the Trojans and well-greaved Achaeans should long suffer pains on behalf of such a woman.