The Arms of Achilles: Re-Exchange in the Iliad

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Plutarch's 'Lives' and the Critical Reader

Plutarch's 'Lives' and the critical reader Book or Report Section Published Version Duff, T. (2011) Plutarch's 'Lives' and the critical reader. In: Roskam, G. and Van der Stockt, L. (eds.) Virtues for the people: aspects of Plutarch's ethics. Plutarchea Hypomnemata (4). Leuven University Press, Leuven, pp. 59-82. ISBN 9789058678584 Available at http://centaur.reading.ac.uk/24388/ It is advisable to refer to the publisher’s version if you intend to cite from the work. See Guidance on citing . Publisher: Leuven University Press All outputs in CentAUR are protected by Intellectual Property Rights law, including copyright law. Copyright and IPR is retained by the creators or other copyright holders. Terms and conditions for use of this material are defined in the End User Agreement . www.reading.ac.uk/centaur CentAUR Central Archive at the University of Reading Reading’s research outputs online Reprint from Virtues for the People. Aspects of Plutarchan Ethics - ISBN 978 90 5867 858 4 - Leuven University Press virtues for the people aspects of plutarchan ethics Reprint from Virtues for the People. Aspects of Plutarchan Ethics - ISBN 978 90 5867 858 4 - Leuven University Press PLUTARCHEA HYPOMNEMATA Editorial Board Jan Opsomer (K.U.Leuven) Geert Roskam (K.U.Leuven) Frances Titchener (Utah State University, Logan) Luc Van der Stockt (K.U.Leuven) Advisory Board F. Alesse (ILIESI-CNR, Roma) M. Beck (University of South Carolina, Columbia) J. Beneker (University of Wisconsin, Madison) H.-G. Ingenkamp (Universität Bonn) A.G. Nikolaidis (University of Crete, Rethymno) Chr. Pelling (Christ Church, Oxford) A. Pérez Jiménez (Universidad de Málaga) Th. -

Naming the Extrasolar Planets

Naming the extrasolar planets W. Lyra Max Planck Institute for Astronomy, K¨onigstuhl 17, 69177, Heidelberg, Germany [email protected] Abstract and OGLE-TR-182 b, which does not help educators convey the message that these planets are quite similar to Jupiter. Extrasolar planets are not named and are referred to only In stark contrast, the sentence“planet Apollo is a gas giant by their assigned scientific designation. The reason given like Jupiter” is heavily - yet invisibly - coated with Coper- by the IAU to not name the planets is that it is consid- nicanism. ered impractical as planets are expected to be common. I One reason given by the IAU for not considering naming advance some reasons as to why this logic is flawed, and sug- the extrasolar planets is that it is a task deemed impractical. gest names for the 403 extrasolar planet candidates known One source is quoted as having said “if planets are found to as of Oct 2009. The names follow a scheme of association occur very frequently in the Universe, a system of individual with the constellation that the host star pertains to, and names for planets might well rapidly be found equally im- therefore are mostly drawn from Roman-Greek mythology. practicable as it is for stars, as planet discoveries progress.” Other mythologies may also be used given that a suitable 1. This leads to a second argument. It is indeed impractical association is established. to name all stars. But some stars are named nonetheless. In fact, all other classes of astronomical bodies are named. -

ON TRANSLATING the POETRY of CATULLUS by Susan Mclean

A publication of the American Philological Association Vol. 1 • Issue 2 • fall 2002 From the Editors REMEMBERING RHESUS by Margaret A. Brucia and Anne-Marie Lewis by C. W. Marshall uripides wrote a play called Rhesus, position in the world of myth. Hector, elcome to the second issue of Eand a play called Rhesus is found leader of the Trojan forces, sees the WAmphora. We were most gratified among the extant works of Euripi- opportunity for a night attack on the des. Nevertheless, scholars since antiq- Greek camp but is convinced first to by the response to the first issue, and we uity have doubted whether these two conduct reconnaissance (through the thank all those readers who wrote to share plays are the same, suggesting instead person of Dolon) and then to await rein- with us their enthusiasm for this new out- that the Rhesus we have is not Euripi- forcements (in the person of Rhesus). reach initiative and to tell us how much dean. This question of dubious author- Odysseus and Diomedes, aided by the they enjoyed the articles and reviews. ship has eclipsed many other potential goddess Athena, frustrate both of these Amphora is very much a communal project areas of interest concerning this play enterprises so that by morning, when and, as a result, it is too often sidelined the attack is to begin, the Trojans are and, as we move forward into our second in discussions of classical tragedy, when assured defeat. issue, we would like to thank those who it is discussed at all. George Kovacs For me, the most exciting part of the have been so helpful to us: Adam Blistein, wanted to see how the play would work performance happened out of sight of Executive Director of the American Philo- on stage and so offered to direct it to the audience. -

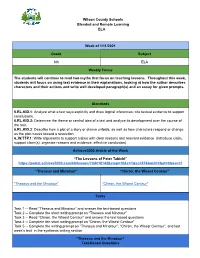

Ms. Legrange's Lesson Plans

Wilson County Schools Blended and Remote Learning ELA Week of 1/11/2021 Grade Subject 6th ELA Weekly Focus The students will continue to read two myths that focus on teaching lessons. Throughout this week, students will focus on using text evidence in their explanations, looking at how the author describes characters and their actions and write well developed paragraph(s) and an essay for given prompts. Standards 6.RL.KID.1: Analyze what a text says explicitly and draw logical inferences; cite textual evidence to support conclusions. 6.RL.KID.2: Determine the theme or central idea of a text and analyze its development over the course of the text. 6.RL.KID.3: Describe how a plot of a story or drama unfolds, as well as how characters respond or change as the plot moves toward a resolution. 6..W.TTP.1 : Write arguments to support claims with clear reasons and relevant evidence (introduce claim, support claim(s), organize reasons and evidence, effective conclusion). Achieve3000 Article of the Week “The Lessons of Peter Tabichi” https://portal.achieve3000.com/kb/lesson/?lid=18142&step=10&c=1&sc=276&oid=0&ot=0&asn=1 “Theseus and Minotaur” “Chiron, the Wisest Centaur” "Theseus and the Minotaur" "Chiron, the Wisest Centaur" Tasks Task 1 -- Read “Theseus and Minotaur” and answer the text-based questions Task 2 -- Complete the short writing prompt on “Theseus and Minotaur” Task 3 -- Read ”Chiron, the Wisest Centaur” and answer the text-based questions Task 4 -- Complete the short writing prompt on “Chiron, the Wisest Centaur” Task 5 -- Complete the writing prompt on “Theseus and Minotaur”, “Chiron, the Wisest Centaur”, and last week’s text in the synthesis writing section. -

Sons and Fathers in the Catalogue of Argonauts in Apollonius Argonautica 1.23-233

Sons and fathers in the catalogue of Argonauts in Apollonius Argonautica 1.23-233 ANNETTE HARDER University of Groningen [email protected] 1. Generations of heroes The Argonautica of Apollonius Rhodius brings emphatically to the attention of its readers the distinction between the generation of the Argonauts and the heroes of the Trojan War in the next genera- tion. Apollonius initially highlights this emphasis in the episode of the Argonauts’ departure, when the baby Achilles is watching them, at AR 1.557-5581 σὺν καί οἱ (sc. Chiron) παράκοιτις ἐπωλένιον φορέουσα | Πηλείδην Ἀχιλῆα, φίλωι δειδίσκετο πατρί (“and with him his wife, hold- ing Peleus’ son Achilles in her arms, showed him to his dear father”)2; he does so again in 4.866-879, which describes Thetis and Achilles as a baby. Accordingly, several scholars have focused on the ways in which 1 — On this marker of the generations see also Klooster 2014, 527. 2 — All translations of Apollonius are by Race 2008. EuGeStA - n°9 - 2019 2 ANNETTE HARDER Apollonius has avoided anachronisms by carefully distinguishing between the Argonauts and the heroes of the Trojan War3. More specifically Jacqueline Klooster (2014, 521-530), in discussing the treatment of time in the Argonautica, distinguishes four periods of time to which Apollonius refers: first, the time before the Argo sailed, from the beginning of the cosmos (featured in the song of Orpheus in AR 1.496-511); second, the time of its sailing (i.e. the time of the epic’s setting); third, the past after the Argo sailed and fourth the present inhab- ited by the narrator (both hinted at by numerous allusions and aitia). -

Homer and Greek Epic

HomerHomer andand GreekGreek EpicEpic INTRODUCTION TO HOMERIC EPIC (CHAPTER 4.IV) • The Iliad, Books 23-24 • Overview of The Iliad, Books 23-24 • Analysis of Book 24: The Death-Journey of Priam •Grammar 4: Review of Parts of Speech: Nouns, Verbs, Adjectives, Adverbs, Pronouns, Prepositions and Conjunctions HomerHomer andand GreekGreek EpicEpic INTRODUCTION TO HOMERIC EPIC (CHAPTER 4.IV) Overview of The Iliad, Book 23 • Achilles holds funeral games in honor of Patroclus • these games serve to reunite the Greeks and restore their sense of camaraderie • but the Greeks and Trojans are still at odds • Achilles still refuses to return Hector’s corpse to his family HomerHomer andand GreekGreek EpicEpic INTRODUCTION TO HOMERIC EPIC (CHAPTER 4.IV) Overview of The Iliad, Book 24 • Achilles’ anger is as yet unresolved • the gods decide he must return Hector’s body • Zeus sends Thetis to tell him to inform him of their decision • she finds Achilles sulking in his tent and he agrees to accept ransom for Hector’s body HomerHomer andand GreekGreek EpicEpic INTRODUCTION TO HOMERIC EPIC (CHAPTER 4.IV) Overview of The Iliad, Book 24 • the gods also send a messenger to Priam and tell him to take many expensive goods to Achilles as a ransom for Hector’s body • he sneaks into the Greek camp and meets with Achilles • Achilles accepts Priam’s offer of ransom and gives him Hector’s body HomerHomer andand GreekGreek EpicEpic INTRODUCTION TO HOMERIC EPIC (CHAPTER 4.IV) Overview of The Iliad, Book 24 • Achilles and Priam arrange an eleven-day moratorium on fighting -

MONEY and the EARLY GREEK MIND: Homer, Philosophy, Tragedy

This page intentionally left blank MONEY AND THE EARLY GREEK MIND How were the Greeks of the sixth century bc able to invent philosophy and tragedy? In this book Richard Seaford argues that a large part of the answer can be found in another momentous development, the invention and rapid spread of coinage, which produced the first ever thoroughly monetised society. By transforming social relations, monetisation contributed to the ideas of the universe as an impersonal system (presocratic philosophy) and of the individual alienated from his own kin and from the gods (in tragedy). Seaford argues that an important precondition for this monetisation was the Greek practice of animal sacrifice, as represented in Homeric epic, which describes a premonetary world on the point of producing money. This book combines social history, economic anthropology, numismatics and the close reading of literary, inscriptional, and philosophical texts. Questioning the origins and shaping force of Greek philosophy, this is a major book with wide appeal. richard seaford is Professor of Greek Literature at the University of Exeter. He is the author of commentaries on Euripides’ Cyclops (1984) and Bacchae (1996) and of Reciprocity and Ritual: Homer and Tragedy in the Developing City-State (1994). MONEY AND THE EARLY GREEK MIND Homer, Philosophy, Tragedy RICHARD SEAFORD cambridge university press Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, Madrid, Cape Town, Singapore, São Paulo Cambridge University Press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge cb2 2ru, UK Published in the United States of America by Cambridge University Press, New York www.cambridge.org Information on this title: www.cambridge.org/9780521832281 © Richard Seaford 2004 This publication is in copyright. -

Dares Phrygius' De Excidio Trojae Historia: Philological Commentary and Translation

Faculteit Letteren & Wijsbegeerte Dares Phrygius' De Excidio Trojae Historia: Philological Commentary and Translation Jonathan Cornil Scriptie voorgedragen tot het bekomen van de graad van Master in de Taal- en letterkunde (Latijn – Engels) 2011-2012 Promotor: Prof. Dr. W. Verbaal ii Table of Contents Table of Contents iii Foreword v Introduction vii Chapter I. De Excidio Trojae Historia: Philological and Historical Comments 1 A. Dares and His Historia: Shrouded in Mystery 2 1. Who Was ‘Dares the Phrygian’? 2 2. The Role of Cornelius Nepos 6 3. Time of Origin and Literary Environment 9 4. Analysing the Formal Characteristics 11 B. Dares as an Example of ‘Rewriting’ 15 1. Homeric Criticism and the Trojan Legacy in the Middle Ages 15 2. Dares’ Problematic Connection with Dictys Cretensis 20 3. Comments on the ‘Lost Greek Original’ 27 4. Conclusion 31 Chapter II. Translations 33 A. Translating Dares: Frustra Laborat, Qui Omnibus Placere Studet 34 1. Investigating DETH’s Style 34 2. My Own Translations: a Brief Comparison 39 3. A Concise Analysis of R.M. Frazer’s Translation 42 B. Translation I 50 C. Translation II 73 D. Notes 94 Bibliography 95 Appendix: the Latin DETH 99 iii iv Foreword About two years ago, I happened to be researching Cornelius Nepos’ biography of Miltiades as part of an assignment for a class devoted to the study of translating Greek and Latin texts. After heaping together everything I could find about him in the library, I came to the conclusion that I still needed more information. So I decided to embrace my identity as a loyal member of the ‘Internet generation’ and began my virtual journey through the World Wide Web in search of articles on Nepos. -

Breaking the Silence of Homer's Women in Pat Barker's the Silence

International Journal of English Language Studies (IJELS) ISSN: 2707-7578 DOI: 10.32996/ijels Website: https://al-kindipublisher.com/index.php/ijels Breaking the Silence of Homer’s Women in Pat Barker’s the Silence of The Girls Indrani A. Borgohain Ph.D. Candidate, University of Jordan, Amman, Jordan Corresponding Author: Indrani A. Borgohain, E-mail: [email protected] ARTICLE INFORMATION ABSTRACT Received: December 25, 2020 Since time immemorial, women have been silenced by patriarchal societies in most, if Accepted: February 10, 2021 not all, cultures. Women voices are ignored, belittled, mocked, interrupted or shouted Volume: 3 down. The aim of this study examines how the contemporary writer Pat Barker breaks Issue: 2 the silence of Homer’s women in her novel The Silence of The Girl (2018). A semantic DOI: 10.32996/ijels.2021.3.2.2 interplay will be conducted with the themes in an attempt to show how Pat Barker’s novel fit into the Greek context of the Trojan War. The Trojan War begins with the KEYWORDS conflict between the kingdoms of Troy and Mycenaean Greece. Homer’s The Iliad, a popular story in the mythological of ancient Greece, gives us the story from the The Iliad, Intertextuality, perspective of the Greeks, whereas Pat Barker’s new novel gives us the story from the Adaptation, palimpsestic, Trojan perspective of the queen- turned slave Briseis. Pat Barker’s, The Silence of the Girls, War, patriarchy, feminism written in 2018, readdresses The Iliad to uncover the unvoiced tale of Achilles’ captive, who is none other than Briseis. In the Greek saga, Briseis is the wife of King Mynes of Lyrnessus, an ally of Troy. -

Miscellanea a Repetition in the Myrmidons Of

MISCELLANEA A REPETITION IN THE MYRMIDONS OF AESCHYLUS I recently suggested that Mette F 224, may be used to restore POx 2163, 6, and that the fragment belongs to the Myrmidons of Aeschylus 1). Although the correlation of three letters is not strong evidence for this restoration and attribution 2), an allusion in Aristophanes' Frogs to r ypoq 3), in combination with Trypho's reason for quoting the lines 4), makes the suggestion more plausible. At line g28 of the Frogs, Euripides criticizes Aeschylus for using the words and i«cpPoS. Aristophanes seems to have the Achilleis trilogy in mind in this section of the play 5) and Euripides seems to be criticizing the overuse of the word Tr«cppos (it is in the plural and certainly is not one of the 'horse-cliffed' words such as ypu7taLé1'ouç and (g29). It is thus possible that Aristophanes is alluding to our fragment in which 7a'ypoq appears (elsewhere in Aeschylus only Mette, F 201) and that, since he implies the word was overused, it is repeated in the Myrmidons. Trypho quotes the lines because they contain a figure of speech. After the quotation, he says: yccp cxvd rou axPysia.c. Trypho is illustrating a figure of speech in which the author used rpc18mxi« to mean 'accuracy' instead of the more common meaning 'sparing'. In the lines themselves, the word describes Teucer's success with his bow in stopping the Phrygians, who were attempt- ing to leap over the ditch (vid. Iliad 12, Ajax and Teucer success- I) C. P. 66 (1971), 112. -

An Analysis of Heracles As a Tragic Hero in the Trachiniae and the Heracles

The Suffering Heracles: An Analysis of Heracles as a Tragic Hero in The Trachiniae and the Heracles by Daniel Rom Thesis presented for the Master’s Degree in Ancient Cultures in the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, at Stellenbosch University Supervisor: Prof. Annemaré Kotzé March 2016 Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Declaration By submitting this thesis electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own, original work, that I am the sole author thereof (save to the extent explicitly otherwise stated), that reproduction and publication thereof by Stellenbosch University will not infringe any third party rights and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. March 2016 Copyright © 2016 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Abstract This thesis is an examination of the portrayals of the Ancient Greek mythological hero Heracles in two fifth century BCE tragic plays: The Trachiniae by Sophocles, and the Heracles by Euripides. Based on existing research that was examined, this thesis echoes the claim made by several sources that there is a conceptual link between both these plays in terms of how they treat Heracles as a character on stage. Fundamentally, this claim is that these two plays portray Heracles as a suffering, tragic figure in a way that other theatre portrayals of him up until the fifth century BCE had failed to do in such a notable manner. This thesis links this claim with a another point raised in modern scholarship: specifically, that Heracles‟ character and development as a mythical hero in the Ancient Greek world had given him a distinct position as a demi-god, and this in turn affected how he was approached as a character on stage. -

1 Divine Intervention and Disguise in Homer's Iliad Senior Thesis

Divine Intervention and Disguise in Homer’s Iliad Senior Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Undergraduate School of Arts and Sciences Brandeis University Undergraduate Program in Classical Studies Professor Joel Christensen, Advisor In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts By Joana Jankulla May 2018 Copyright by Joana Jankulla 1 Copyright by Joana Jankulla © 2018 2 Acknowledgements First and foremost, I would like to thank my advisor, Professor Joel Christensen. Thank you, Professor Christensen for guiding me through this process, expressing confidence in me, and being available whenever I had any questions or concerns. I would not have been able to complete this work without you. Secondly, I would like to thank Professor Ann Olga Koloski-Ostrow and Professor Cheryl Walker for reading my thesis and providing me with feedback. The Classics Department at Brandeis University has been an instrumental part of my growth in my four years as an undergraduate, and I am eternally thankful to all the professors and staff members in the department. Thank you to my friends, specifically Erica Theroux, Sarah Jousset, Anna Craven, Rachel Goldstein, Taylor McKinnon and Georgie Contreras for providing me with a lot of emotional support this year. I hope you all know how grateful I am for you as friends and how much I have appreciated your love this year. Thank you to my mom for FaceTiming me every time I was stressed about completing my thesis and encouraging me every step of the way. Finally, thank you to Ian Leeds for dropping everything and coming to me each time I needed it.