The Grotesque As It Appears in Western Art History and in Ian Marley’S Creative Creatures

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Analysis of Heracles As a Tragic Hero in the Trachiniae and the Heracles

The Suffering Heracles: An Analysis of Heracles as a Tragic Hero in The Trachiniae and the Heracles by Daniel Rom Thesis presented for the Master’s Degree in Ancient Cultures in the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, at Stellenbosch University Supervisor: Prof. Annemaré Kotzé March 2016 Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Declaration By submitting this thesis electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own, original work, that I am the sole author thereof (save to the extent explicitly otherwise stated), that reproduction and publication thereof by Stellenbosch University will not infringe any third party rights and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. March 2016 Copyright © 2016 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Abstract This thesis is an examination of the portrayals of the Ancient Greek mythological hero Heracles in two fifth century BCE tragic plays: The Trachiniae by Sophocles, and the Heracles by Euripides. Based on existing research that was examined, this thesis echoes the claim made by several sources that there is a conceptual link between both these plays in terms of how they treat Heracles as a character on stage. Fundamentally, this claim is that these two plays portray Heracles as a suffering, tragic figure in a way that other theatre portrayals of him up until the fifth century BCE had failed to do in such a notable manner. This thesis links this claim with a another point raised in modern scholarship: specifically, that Heracles‟ character and development as a mythical hero in the Ancient Greek world had given him a distinct position as a demi-god, and this in turn affected how he was approached as a character on stage. -

Classical Images – Greek Pegasus

Classical images – Greek Pegasus Red-figure kylix crater Attic Red-figure kylix Triptolemus Painter, c. 460 BC attr Skythes, c. 510 BC Edinburgh, National Museums of Scotland Boston, MFA (source: theoi.com) Faliscan black pottery kylix Athena with Pegasus on shield Black-figure water jar (Perseus on neck, Pegasus with Etrurian, attr. the Sokran Group, c. 350 BC Athenian black-figure amphora necklace of bullae (studs) and wings on feet, Centaur) London, The British Museum (1842.0407) attr. Kleophrades pntr., 5th C BC From Vulci, attr. Micali painter, c. 510-500 BC 1 New York, Metropolitan Museum of ART (07.286.79) London, The British Museum (1836.0224.159) Classical images – Greek Pegasus Pegasus Pegasus Attic, red-figure plate, c. 420 BC Source: Wikimedia (Rome, Palazzo Massimo exh) 2 Classical images – Greek Pegasus Pegasus London, The British Museum Virginia, Museum of Fine Arts exh (The Horse in Art) Pegasus Red-figure oinochoe Apulian, c. 320-10 BC 3 Boston, MFA Classical images – Greek Pegasus Silver coin (Pegasus and Athena) Silver coin (Pegasus and Lion/Bull combat) Corinth, c. 415-387 BC Lycia, c. 500-460 BC London, The British Museum (Ac RPK.p6B.30 Cor) London, The British Museum (Ac 1979.0101.697) Silver coin (Pegasus protome and Warrior (Nergal?)) Silver coin (Arethusa and Pegasus Levantine, 5th-4th C BC Graeco-Iberian, after 241 BC London, The British Museum (Ac 1983, 0533.1) London, The British Museum (Ac. 1987.0649.434) 4 Classical images – Greek (winged horses) Pegasus Helios (Sol-Apollo) in his chariot Eos in her chariot Attic kalyx-krater, c. -

The Arms of Achilles: Re-Exchange in the Iliad

The Arms of Achilles: Re-Exchange in the Iliad by Eirene Seiradaki A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of Classics University of Toronto © Copyright by Eirene Seiradaki (2014) “The Arms of Achilles: Re-Exchange in the Iliad ” Eirene Seiradaki Doctor of Philosophy Department of Classics University of Toronto 2014 Abstract This dissertation offers an interpretation of the re-exchange of the first set of Achilles’ arms in the Iliad by gift, loan, capture, and re-capture. Each transfer of the arms is examined in relation to the poem’s dramatic action, characterisation, and representation of social institutions and ethical values. Modern anthropological and economic approaches are employed in order to elucidate standard elements surrounding certain types of exchange. Nevertheless, the study primarily involves textual analysis of the Iliadic narratives recounting the circulation-process of Achilles’ arms, with frequent reference to the general context of Homeric exchange and re-exchange. The origin of the armour as a wedding gift to Peleus for his marriage to Thetis and its consequent bequest to Achilles signifies it as the hero’s inalienable possession and marks it as the symbol of his fate in the Iliad . Similarly to the armour, the spear, a gift of Cheiron to Peleus, is later inherited by his son. Achilles’ own bond to Cheiron makes this weapon another inalienable possession of the hero. As the centaur’s legacy to his pupil, the spear symbolises Achilles’ awareness of his coming death. In the present time of the Iliad , ii Achilles lends his armour to Patroclus under conditions that indicate his continuing ownership over his panoply and ensure the safe use of the divine weapons by his friend. -

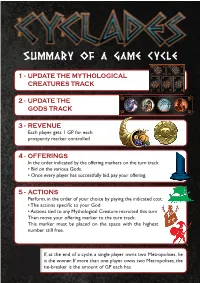

Summary of a Game Cycle

SUMMARY OF A GAME CYCLE 1 - UPDATE THE MYTHOLOGICAL CREATURES TRACK 2 - UPDATE THE GODS TRACK 3 - REVENUE Each player gets 1 GP for each prosperity marker controlled 4 - OFFERINGS In the order indicated by the offering markers on the turn track: s"IDONTHEVARIOUS'ODS s/NCEEVERYPLAYERHASSUCCESSFULLYBID PAYYOUROFFERING 5 - ACTIONS 0ERFORM INTHEORDEROFYOURCHOICEBYPAYINGTHEINDICATEDCOST s4HEACTIONSSPECIlCTOYOUR'OD s!CTIONSTIEDTOANY-YTHOLOGICAL#REATURERECRUITEDTHISTURN 4HENMOVEYOUROFFERINGMARKERTOTHETURNTRACK 4HIS MARKER MUST BE PLACED ON THE SPACE WITH THE HIGHEST NUMBERSTILLFREE )F ATTHEENDOFACYCLE ASINGLEPLAYEROWNSTWO-ETROPOLISES HE ISTHEWINNER)FMORETHANONEPLAYEROWNSTWO-ETROPOLISES THE TIE BREAKERISTHEAMOUNTOF'0EACHHAS MYTHOLOGICAL CREATURES THE FATES SATYR DRYAD Recieve your revenue again, just like Steal a Philosopher from the player Steal a Priest from the player of SIREN PEGASUS GIANT at the beginning of the Cycle. of your choice. your choice. Remove an opponent’s fleet from Designate one of your isles and Destroy a building. This action can the board and replace it with one move some or all of the troops on be used to slow down an opponent of yours. If you no longer have any it to another isle without having to or remove a troublesome Fortress. The Kraken, the Minotaur, Chiron, The following 4 creatures work the same way: place the figurine on the isle of fleets in reserve, you can take one have a chain of fleets. This creature The Giant cannot destroy a Metro- Medusa and Polyphemus have a your choice. The power of the creature is applied to the isle where it is until from somewhere else on the board. is the only way to invade an oppo- polis. figurine representing them as they the beginning of your next turn. -

Natural Chimerism

Natural Chimerism Definitions • Mosaic – two populations of cells with different genotypes in one individual that developed from a single fertilized egg (subset of cells with a mutation) • Hybrid – a cross (mix of chromosomes) between parents of two different (sub)species (horse & donkey > mule & hinny) • Chimera – fusion of cells from different individuals of same or different species that will develop side by side and form a single organism Artificial / Iatrogenic Chimera • Intra-species – bone marrow transplantation – stem cell transplantation – organ transplantation • Inter-species – mouse-human – sheep-goat – etc Chimera (Χίμαιρα, Chímaira, "the goat") ... originally a creature of the Greek mythology http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chimaera_(mythology) Typhon Echidna Cerberus Chimera Hydra Sphinx ? Natural Chimera • Fetal-maternal chimera • Blood sharing and twin chimera • Whole body or dispermic chimera • Tumor chimera • Germ cell chimera Rinkevich, Human Immunol 62:651 (2001) Gandparents Grandparents Mother Father Someone Someone Monozygotic Dizygotic Sister twins twins Brother Natural Chimera • Fetal-maternal chimera • Blood sharing and twin chimera • Whole body or dispermic chimera • Tumor chimera • Germ cell chimera Rinkevich, Human Immunol 62:651 (2001) Maternal immune system and pregnancy Placenta is a tumor Child is a parasite Kinsley & Lambert, Scientific American p.72 (01/2006) Nelson, Scientific American p.72 (02/2008) Maternal Instruction to Fetal Cells Self-defense versus immune tolerance Too much restraint of immunity: -

Greek Monsters and Creatures

Name ___________________________________ Date ____________________________ ELA Period ________ Ms. Hidalgo Greek Monsters and Creatures Directions: You will use this paper to record your notes about the different aspects of your assigned monster or creature. This information will be used to write a paragraph introducing your creature from the 1st person point of view. Name of Monster/Creature: Special Powers/Strengths: Physical Description: Role in Greek Mythology: Rivals: Symbols Associated with your Monster/Creature: Relatives: Other Interesting Information: Name ___________________________________ Date ____________________________ ELA Period ________ Ms. Hidalgo Greek Monsters and Creatures Directions: You will be assigned one of the Greek mythological creatures or monsters to research. You will be responsible for creating a power point slide that teaches your classmates about your mythological creature/monster. You will eventually be writing a script and narrating your slide from your creature’s point of view (1st person). MYTHOLOGICAL CREATURES ONCE YOU GET YOUR CREATURE/MONSTER 1) Using the websites found on my Satyr Naiads webpage, you will use the space on the Chiron The Furies back of this sheet to record information you are researching. Charon The Sirens Remember, you need good information Centaur The 3 Fates so the class will learn about your creature/monster. (Required elements Pegasus Hesperides are found on the back of this sheet.) Dryads 2) Take your research and begin to write MYTHOLOGICAL MONSTERS your paragraph that you will include on your Power Point slide and also use as your Argus Medusa Typhon script. Chimera Gorgons Scylla Hydra Cyclops Procrustes 3) Search for the picture/pictures (no more than 2) that you will use. -

Constellation Legends

Constellation Legends by Norm McCarter Naturalist and Astronomy Intern SCICON Andromeda – The Chained Lady Cassiopeia, Andromeda’s mother, boasted that she was the most beautiful woman in the world, even more beautiful than the gods. Poseidon, the brother of Zeus and the god of the seas, took great offense at this statement, for he had created the most beautiful beings ever in the form of his sea nymphs. In his anger, he created a great sea monster, Cetus (pictured as a whale) to ravage the seas and sea coast. Since Cassiopeia would not recant her claim of beauty, it was decreed that she must sacrifice her only daughter, the beautiful Andromeda, to this sea monster. So Andromeda was chained to a large rock projecting out into the sea and was left there to await the arrival of the great sea monster Cetus. As Cetus approached Andromeda, Perseus arrived (some say on the winged sandals given to him by Hermes). He had just killed the gorgon Medusa and was carrying her severed head in a special bag. When Perseus saw the beautiful maiden in distress, like a true champion he went to her aid. Facing the terrible sea monster, he drew the head of Medusa from the bag and held it so that the sea monster would see it. Immediately, the sea monster turned to stone. Perseus then freed the beautiful Andromeda and, claiming her as his bride, took her home with him as his queen to rule. Aquarius – The Water Bearer The name most often associated with the constellation Aquarius is that of Ganymede, son of Tros, King of Troy. -

Greek Top Trumps

MINOTAUR CERBERUS A man-eating monster with the head of A huge and powerful three-headed a bull. He was kept i hidden in a dog. He guarded the entrance to the labyrinth on the island of Crete. underworld. MAGIC 3 MAGIC 28 SPEED 48 SPEED 90 LETHALITY 88 LETHALITY 82 STRENGTH 85 STRENGTH 45 MORALITY -48 MORALITY -84 HYDRA CHIMERA A massive and poisonous serpent with A monstrous fire-breathing creature nine heads. Every time one head was made of the body of a lioness with a injured, another two grew in its place. snake tail and a goat’s head on his back. MAGIC 5 MAGIC 28 SPEED 10 SPEED 58 LETHALITY 94 LETHALITY 62 STRENGTH 82 STRENGTH 87 MORALITY -45 MORALITY 2 GRIFFIN UNICORN A fabulous creature with the head and A pure white horse-like creature with a wings of an eagle and the body of a long horn in the middle of its forehead. lion. MAGIC 49 MAGIC 95 SPEED 28 SPEED 84 LETHALITY 0 LETHALITY 35 STRENGTH 84 STRENGTH 50 MORALITY 100 MORALITY 100 CENTAUR CYCLOPS A creature which was half man and half Giants with a single eye in the middle of horse. its forehead. They made lightning and thunderbolts for Zeus to use. MAGIC 25 MAGIC 2 SPEED 95 SPEED 5 LETHALITY 10 LETHALITY 74 STRENGTH 20 STRENGTH 90 MORALITY 50 MORALITY -10 BASILISK PEGASUS The basilisk was the King of the snakes Pegasus sprang from the blood of the and the most poisonous creature on Gorgon Medusa when the hero Perseus earth. -

Fantastic Creatures and Where to Find Them in the Iliad

DOSSIÊ | DOSSIER Classica, e-ISSN 2176-6436, v. 32, n. 2, p. 235-252, 2019 FANTASTIC CREATURES AND WHERE TO FIND THEM IN THE ILIAD Camila Aline Zanon* * Post-doctoral researcher at the Departamento de Recebido em: 04/10/2019 Letras Clássicas Aprovado em: 25/10/2019 e Vernáculas, Universidade de São Paulo, grant 2016 / 26069-5 São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP). ABSTRACT: As a poem centered on war, the Iliad is not considered [email protected] to be endowed with the element of the fantastic as is the Odyssey. There are, however, mentions or allusions to some creatures fought by heroes of previous generation, like Heracles and Bellerophon, along with some brief mentions to other fantastic creatures, like the Gorgon, the centaurs, Briareus and Typhon. This paper aims to locate those brief presences in the broader narrative frame of the Iliad. KEYWORDS: Early Greek epic poetry; Homer; Iliad; monsters. CRIATURAS FANTÁSTICAS E ONDE ENCONTRÁ-LAS NA ILÍADA RESUMO: Enquanto um poema centrado na guerra, não se considera que a Ilíada seja dotada do elemento fantástico como a Odisseia. Há, contudo, menções ou alusões a algumas criaturas combatidas por heróis da geração anterior, como Héracles e Belerofonte, junto com algumas breves menções a outras criaturas fantásticas, como a Górgona, os centauros, Briareu e Tífon. Este artigo pretende localizar essas breves presenças no enquadramento narrativo mais amplo da Ilíada. PALAVRAS-CHAVE: Poesia épica grega arcaica; Homero; Ilíada; monstros. DOI: https://doi.org/10.24277/classica.v32i2.880 236 Camila Aline Zanon INTRODUCTION1 n his ‘The epic cycle and the uniqueness of Homer,’ Jasper Griffin (1977) sets the different attitudes relating to the fantastic as a criterion for establishing the superiority Iof Homer’s poems over the Epic Cycle. -

7/21/04 9:48 AM Page 332

Leonardo_37-4_265- 7/21/04 9:48 AM Page 332 Downloaded from http://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/pdf/10.1162/0024094041724472 by guest on 24 September 2021 Leonardo_37-4_265- 7/21/04 9:49 AM Page 333 AB GENERAL ARTICLE RI TO L AO NG Chimera Contemporary: DY The Enduring Art of the Composite Beast ABSTRACT The author examines the history of artists’ depictions of Dave Powell fanciful organisms that are formed by combining parts of various species. Broadly tracing the progression of this pursuit from prehistory through the Ancient, Renaissance and Romantic Periods and up to the 20th century and contemporary he aesthetic of the composite animal form has the different branches are gov- T genetic art, the article analyzes been a persistent presence from the primordial depths of erned by distinctly different genetic the seemingly consistent effort human culture to the present dawn of the genetic age. codes. to render these forms simultane- Throughout the course of history, whenever artists have ren- ously nonthreatening or vulnera- dered subjects by melding the physiology of different species, ble in attitude and visually HIMERIC ENDITIONS realistic. The author asks they have almost invariably utilized techniques to render the C R : NCIENT THROUGH whether this practice, which subject visually plausible and pseudo-realistic. Yet perhaps A seems to stem from aesthetic more importantly, chimerical creatures are also commonly CLASSICAL concerns, is sufficiently critical rendered as vulnerable: depicted in either playful or serene Some 10 to 15 millennia have in regards to current trends in genetic engineering. poses, in a state of dying or suffering defeat, or as simply nonag- passed since the stag-antlered, tail- gressive. -

Embodying the Chimera : Toward a Phenobiological Subjectivity ” Bernard Andrieu

Embodying the Chimera : toward a phenobiological subjectivity ” Bernard Andrieu To cite this version: Bernard Andrieu. Embodying the Chimera : toward a phenobiological subjectivity ”. Eduardo Zac ed. Signs of Life, BiotArt And Beyond, M.I.T. Press, p. 57-68., 2007. hal-00447815 HAL Id: hal-00447815 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00447815 Submitted on 15 Jan 2010 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. 3 Embodying the Chimera: Biotechnology and Subjectivity Bernard Andrieu ‘‘Chacun d’eux portait sur son dos une e´norme Chime`re’’ [Each one of them carried on his back an enormous Chimera] —Baudelaire, Le Spleen de Paris, bk. VI Until the end of the seventeenth century, the monstrous body had a mythological func- tion: A sign from irate gods, the monster (Kapler 1980) is not malformed like Oedipus’s twisted foot/fate, it is a prodigious creature whose corporeal formation endows it with superior power. However, one must differentiate between fabulous monsters, whose corpo- real hybridization remains paradoxical, and biological monsters studied as early as Hippo- crates in Of Generation, X-I, and Aristotle in Of the Generation of Animals, Book IV. -

The Chimaera of Arezzo | Exhibition Checklist

The Chimaera of Arezzo | Exhibition Checklist The Chimaera of Arezzo July 16, 2009 to February 8, 2010 The J. Paul Getty Museum at the Getty Villa EXHIBITION CHECKLIST 1) The Chimaera of Arezzo Etruscan, about 400 B.C.; found in Arezzo Bronze, Ht 78.5 cm, L 129 cm Museo Archeologico Nazionale, Florence, inv. 1 A large-scale bronze of the legendary three-headed beast, this sculpture was originally a single element in a group composition that included Bellerophon and Pegasus. On its foreleg is a dedicatory inscription to the supreme Etruscan deity, Tinia. M. Iozzo, ed., The Chimaera of Arezzo, Florence 2009. 2) Lakonian Black-Figured Kylix Attributed to the Boreads Painter, about 565 B.C. Terracotta, Ht 12.5 cm, Diam 18.5 cm The J. Paul Getty Museum, 85.AE.121 In an unusual heraldic composition decorating the tondo of this cup, the Chimaera fends off the hooves of Pegasus while Bellerophon crouches below, thrusting his spear into the monster’s shaggy belly. As in Attic iconography, the Chimaera turns its lion head away from the attack. C. Stibbe, “Bellerophon and the Chimaira on a Lakonian Cup by the Boreads Painter,” Greek Vases in the J. Paul Getty Museum 5, 1991, pp. 5–12. 3) Lucanian Red-Figured Amphora (Panathenaic Shape) Attributed to the Pisticci-Amykos Group, about 420 B.C.; found in Ruvo di Puglia Terracotta, Ht 63 cm Museo Archeologico Nazionale, Naples, inv. 82263 On the shoulder, Stheneboea and Pegasus look on as King Proetus bids farewell to Bellerophon, who holds a sealed tablet commanding his death.