Phoenix in the Iliad

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Hellenic Saga Gaia (Earth)

The Hellenic Saga Gaia (Earth) Uranus (Heaven) Oceanus = Tethys Iapetus (Titan) = Clymene Themis Atlas Menoetius Prometheus Epimetheus = Pandora Prometheus • “Prometheus made humans out of earth and water, and he also gave them fire…” (Apollodorus Library 1.7.1) • … “and scatter-brained Epimetheus from the first was a mischief to men who eat bread; for it was he who first took of Zeus the woman, the maiden whom he had formed” (Hesiod Theogony ca. 509) Prometheus and Zeus • Zeus concealed the secret of life • Trick of the meat and fat • Zeus concealed fire • Prometheus stole it and gave it to man • Freidrich H. Fuger, 1751 - 1818 • Zeus ordered the creation of Pandora • Zeus chained Prometheus to a mountain • The accounts here are many and confused Maxfield Parish Prometheus 1919 Prometheus Chained Dirck van Baburen 1594 - 1624 Prometheus Nicolas-Sébastien Adam 1705 - 1778 Frankenstein: The Modern Prometheus • Novel by Mary Shelly • First published in 1818. • The first true Science Fiction novel • Victor Frankenstein is Prometheus • As with the story of Prometheus, the novel asks about cause and effect, and about responsibility. • Is man accountable for his creations? • Is God? • Are there moral, ethical constraints on man’s creative urges? Mary Shelly • “I saw the pale student of unhallowed arts kneeling beside the thing he had put together. I saw the hideous phantasm of a man stretched out, and then, on the working of some powerful engine, show signs of life, and stir with an uneasy, half vital motion. Frightful must it be; for supremely frightful would be the effect of any human endeavour to mock the stupendous mechanism of the Creator of the world” (Introduction to the 1831 edition) Did I request thee, from my clay To mould me man? Did I solicit thee From darkness to promote me? John Milton, Paradise Lost 10. -

Essay 2 Sample Responses

Classics / WAGS 23: Second Essay Responses Grading: I replaced names with a two-letter code (A or B followed by another letter) so that I could read the essays anonymously. I grouped essays by levels of success and cross-read those groups to check that the rankings were consistent. Comments on the assignment: Writers found all manner of things to focus on: Night, crying, hospitality, the return of princes from the dead (Hector, Odysseus), and the exchange of bodies (Hector, Penelope). Here are four interesting and quite different responses: Essay #1: Substitution I Am That I Am: The Nature of Identity in the Iliad and the Odyssey The last book of the Iliad, and the penultimate book of the Odyssey, both deal with the issue of substitution; specifically, of accepting a substitute for a lost loved one. Priam and Achilles become substitutes for each others' absent father and dead son. In contrast, Odysseus's journey is fraught with instances of him refusing to take a substitute for Penelope, and in the end Penelope makes the ultimate verification that Odysseus is not one of the many substitutes that she has been offered over the years. In their contrasting depictions of substitution, the endings of the Iliad and the Odyssey offer insights into each epic's depiction of identity in general. Questions of identity are in the foreground throughout much of the Iliad; one need only try to unravel the symbolism and consequences of Patroclus’ donning Achilles' armor to see how this is so. In the interaction between Achilles and Priam, however, they are particularly poignant. -

The Herodotos Project (OSU-Ugent): Studies in Ancient Ethnography

Faculty of Literature and Philosophy Julie Boeten The Herodotos Project (OSU-UGent): Studies in Ancient Ethnography Barbarians in Strabo’s ‘Geography’ (Abii-Ionians) With a case-study: the Cappadocians Master thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master in Linguistics and Literature, Greek and Latin. 2015 Promotor: Prof. Dr. Mark Janse UGent Department of Greek Linguistics Co-Promotores: Prof. Brian Joseph Ohio State University Dr. Christopher Brown Ohio State University ACKNOWLEDGMENT In this acknowledgment I would like to thank everybody who has in some way been a part of this master thesis. First and foremost I want to thank my promotor Prof. Janse for giving me the opportunity to write my thesis in the context of the Herodotos Project, and for giving me suggestions and answering my questions. I am also grateful to Prof. Joseph and Dr. Brown, who have given Anke and me the chance to be a part of the Herodotos Project and who have consented into being our co- promotores. On a whole other level I wish to express my thanks to my parents, without whom I would not have been able to study at all. They have also supported me throughout the writing process and have read parts of the draft. Finally, I would also like to thank Kenneth, for being there for me and for correcting some passages of the thesis. Julie Boeten NEDERLANDSE SAMENVATTING Deze scriptie is geschreven in het kader van het Herodotos Project, een onderneming van de Ohio State University in samenwerking met UGent. De doelstelling van het project is het aanleggen van een databank met alle volkeren die gekend waren in de oudheid. -

Ms. Legrange's Lesson Plans

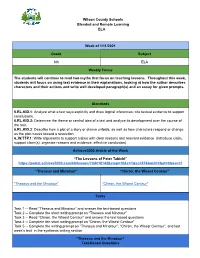

Wilson County Schools Blended and Remote Learning ELA Week of 1/11/2021 Grade Subject 6th ELA Weekly Focus The students will continue to read two myths that focus on teaching lessons. Throughout this week, students will focus on using text evidence in their explanations, looking at how the author describes characters and their actions and write well developed paragraph(s) and an essay for given prompts. Standards 6.RL.KID.1: Analyze what a text says explicitly and draw logical inferences; cite textual evidence to support conclusions. 6.RL.KID.2: Determine the theme or central idea of a text and analyze its development over the course of the text. 6.RL.KID.3: Describe how a plot of a story or drama unfolds, as well as how characters respond or change as the plot moves toward a resolution. 6..W.TTP.1 : Write arguments to support claims with clear reasons and relevant evidence (introduce claim, support claim(s), organize reasons and evidence, effective conclusion). Achieve3000 Article of the Week “The Lessons of Peter Tabichi” https://portal.achieve3000.com/kb/lesson/?lid=18142&step=10&c=1&sc=276&oid=0&ot=0&asn=1 “Theseus and Minotaur” “Chiron, the Wisest Centaur” "Theseus and the Minotaur" "Chiron, the Wisest Centaur" Tasks Task 1 -- Read “Theseus and Minotaur” and answer the text-based questions Task 2 -- Complete the short writing prompt on “Theseus and Minotaur” Task 3 -- Read ”Chiron, the Wisest Centaur” and answer the text-based questions Task 4 -- Complete the short writing prompt on “Chiron, the Wisest Centaur” Task 5 -- Complete the writing prompt on “Theseus and Minotaur”, “Chiron, the Wisest Centaur”, and last week’s text in the synthesis writing section. -

Sons and Fathers in the Catalogue of Argonauts in Apollonius Argonautica 1.23-233

Sons and fathers in the catalogue of Argonauts in Apollonius Argonautica 1.23-233 ANNETTE HARDER University of Groningen [email protected] 1. Generations of heroes The Argonautica of Apollonius Rhodius brings emphatically to the attention of its readers the distinction between the generation of the Argonauts and the heroes of the Trojan War in the next genera- tion. Apollonius initially highlights this emphasis in the episode of the Argonauts’ departure, when the baby Achilles is watching them, at AR 1.557-5581 σὺν καί οἱ (sc. Chiron) παράκοιτις ἐπωλένιον φορέουσα | Πηλείδην Ἀχιλῆα, φίλωι δειδίσκετο πατρί (“and with him his wife, hold- ing Peleus’ son Achilles in her arms, showed him to his dear father”)2; he does so again in 4.866-879, which describes Thetis and Achilles as a baby. Accordingly, several scholars have focused on the ways in which 1 — On this marker of the generations see also Klooster 2014, 527. 2 — All translations of Apollonius are by Race 2008. EuGeStA - n°9 - 2019 2 ANNETTE HARDER Apollonius has avoided anachronisms by carefully distinguishing between the Argonauts and the heroes of the Trojan War3. More specifically Jacqueline Klooster (2014, 521-530), in discussing the treatment of time in the Argonautica, distinguishes four periods of time to which Apollonius refers: first, the time before the Argo sailed, from the beginning of the cosmos (featured in the song of Orpheus in AR 1.496-511); second, the time of its sailing (i.e. the time of the epic’s setting); third, the past after the Argo sailed and fourth the present inhab- ited by the narrator (both hinted at by numerous allusions and aitia). -

Iliad Teacher Sample

CONTENTS Teaching Guidelines ...................................................4 Appendix Book 1: The Anger of Achilles ...................................6 Genealogies ...............................................................57 Book 2: Before Battle ................................................8 Alternate Names in Homer’s Iliad ..............................58 Book 3: Dueling .........................................................10 The Friends and Foes of Homer’s Iliad ......................59 Book 4: From Truce to War ........................................12 Weaponry and Armor in Homer..................................61 Book 5: Diomed’s Day ...............................................14 Ship Terminology in Homer .......................................63 Book 6: Tides of War .................................................16 Character References in the Iliad ...............................65 Book 7: A Duel, a Truce, a Wall .................................18 Iliad Tests & Keys .....................................................67 Book 8: Zeus Takes Charge ........................................20 Book 9: Agamemnon’s Day ........................................22 Book 10: Spies ...........................................................24 Book 11: The Wounded ..............................................26 Book 12: Breach ........................................................28 Book 13: Tug of War ..................................................30 Book 14: Return to the Fray .......................................32 -

Excerpts from Iliad Six (Hector Is the Oldest Son of Troy's King Priam, And

EXCERPTS FROM HOMER Excerpts from Iliad Six (Hector is the oldest son of Troy’s King Priam, and the chief defender of the city. He leaves battle temporarily to return to the city.) Focus questions: 1. What are the main roles of women in this section – i.e., what are the actions of the Trojan women, Theano, Hecuba (the queen, Hector’s mother) and Andromache? 2. How do women’s roles support the survival of the city – or do they? 3. In what ways do women contribute to or detract from a man’s honor? 4. Hector and Andromache’s relationship is perfect in Greek terms – how do they relate to one another? What is the balance of “power”? What roles does each play in the family? Now when Hector reached the Scaean gates and the oak tree, the wives and daughters of the Trojans came running towards him to ask after their sons, brothers, kinsmen, and husbands: he told them to set about praying to the gods, and many were made sorrowful as they heard him. Presently he reached the splendid palace of King Priam, adorned with colonnades of hewn stone. In it there were fifty bedchambers- all of hewn stone- built near one another, where the sons of Priam slept, each with his wedded wife. Opposite these, on the other side the courtyard, there were twelve upper rooms also of hewn stone for Priam's daughters, built near one another, where his sons-in-law slept with their wives. When Hector got there, his fond mother came up to him with Laodice the fairest of her daughters. -

Black Odysseus, White Caesar: When Did "White People" Become "White"? Author(S): James H

Black Odysseus, White Caesar: When Did "White People" Become "White"? Author(s): James H. Dee Source: The Classical Journal, Vol. 99, No. 2 (Dec., 2003 - Jan., 2004), pp. 157-167 Published by: The Classical Association of the Middle West and South Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3298065 . Accessed: 10/01/2014 10:38 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The Classical Association of the Middle West and South is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Classical Journal. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 140.141.14.5 on Fri, 10 Jan 2014 10:38:29 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions BLACK ODYSSEUS, WHITE CAESAR:WHEN DID "WHITE PEOPLE"BECOME "WHITE"? Nil nimium studeo, Caesar,tibi velle placere, nec scire utrumsis albus an aterhomo. Catullus' poem 93 is a famous and cryptic invective against Julius Caesar which concludes with the pointed remark, "I don't care to know whether you are a white or a black man." The phrase is a well-attested proverbial expression for complete in- difference about someone; most of the parallels cited by moderns are already gathered in Erasmus' Adagia at Chilias I, Centuria 6, No. -

Flowers in Greek Mythology

Flowers in Greek Mythology Everybody knows how rich and exciting Greek Mythology is. Everybody also knows how rich and exciting Greek Flora is. Find out some of the famous Greek myths flower inspired. Find out how feelings and passions were mixed together with flowers to make wonderful stories still famous in nowadays. Anemone:The name of the plant is directly linked to the well known ancient erotic myth of Adonis and Aphrodite (Venus). It has been inspired great poets like Ovidius or, much later, Shakespeare, to compose hymns dedicated to love. According to this myth, while Adonis was hunting in the forest, the ex- lover of Aphrodite, Ares, disguised himself as a wild boar and attacked Adonis causing him lethal injuries. Aphrodite heard the groans of Adonis and rushed to him, but it was too late. Aphrodite got in her arms the lifeless body of her beloved Adonis and it is said the she used nectar in order to spray the wood. The mixture of the nectar and blood sprang a beautiful flower. However, the life of this 1 beautiful flower doesn’t not last. When the wind blows, makes the buds of the plant to bloom and then drifted away. This flower is called Anemone because the wind helps the flowering and its decline. Adonis:It would be an omission if we do not mention that there is a flower named Adonis, which has medicinal properties. According to the myth, this flower is familiar to us as poppy meadows with the beautiful red colour. (Adonis blood). Iris: The flower got its name from the Greek goddess Iris, goddess of the rainbow. -

The Truce in Iliad 3 and 4

Building Community Across the Battle- Lines: The Truce in Iliad 3 and 4 The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Elmer, David. 2012. Building Community Across the Battle-Lines: The Truce in Iliad 3 and 4. In Maintaining Peace and Interstate Stability in Archaic and Classical Greece, ed. Julia Wilker, 25-48. Mainz: Verlag Antike. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:33921641 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Open Access Policy Articles, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#OAP Building Community Across the Battle-Lines: The Truce in Iliad 3 and 4 Recent work on interstate relations in early Greece has produced two major revisions of established positions. The first is a welcome reassessment of Bruno Keil’s often-cited characterization of peace as “a contractual interruption of a (natural) state of war.”1 As Victor Alonso has stressed, war was only one possible mode of interaction for early Greek communities, and no more the default than either friendship or the lack of a relationship altogether.2 The second major development is represented by Polly Low’s reconsideration of the widespread assumption that “a strict line can be drawn between domestic and international life”: her work reveals the many ways in which Greek political life blurred the boundaries between intra- and inter-polis relationships.3 From a certain point of view, these two reconfigurations can be seen to be mutually reinforcing. -

1 Divine Intervention and Disguise in Homer's Iliad Senior Thesis

Divine Intervention and Disguise in Homer’s Iliad Senior Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Undergraduate School of Arts and Sciences Brandeis University Undergraduate Program in Classical Studies Professor Joel Christensen, Advisor In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts By Joana Jankulla May 2018 Copyright by Joana Jankulla 1 Copyright by Joana Jankulla © 2018 2 Acknowledgements First and foremost, I would like to thank my advisor, Professor Joel Christensen. Thank you, Professor Christensen for guiding me through this process, expressing confidence in me, and being available whenever I had any questions or concerns. I would not have been able to complete this work without you. Secondly, I would like to thank Professor Ann Olga Koloski-Ostrow and Professor Cheryl Walker for reading my thesis and providing me with feedback. The Classics Department at Brandeis University has been an instrumental part of my growth in my four years as an undergraduate, and I am eternally thankful to all the professors and staff members in the department. Thank you to my friends, specifically Erica Theroux, Sarah Jousset, Anna Craven, Rachel Goldstein, Taylor McKinnon and Georgie Contreras for providing me with a lot of emotional support this year. I hope you all know how grateful I am for you as friends and how much I have appreciated your love this year. Thank you to my mom for FaceTiming me every time I was stressed about completing my thesis and encouraging me every step of the way. Finally, thank you to Ian Leeds for dropping everything and coming to me each time I needed it. -

Select Epigrams from the Greek Anthology

SELECT EPIGRAMS FROM THE GREEK ANTHOLOGY J. W. MACKAIL∗ Fellow of Balliol College, Oxford. PREPARER’S NOTE This book was published in 1890 by Longmans, Green, and Co., London; and New York: 15 East 16th Street. The epigrams in the book are given both in Greek and in English. This text includes only the English. Where Greek is present in short citations, it has been given here in transliterated form and marked with brackets. A chapter of Notes on the translations has also been omitted. eti pou proima leuxoia Meleager in /Anth. Pal./ iv. 1. Dim now and soil’d, Like the soil’d tissue of white violets Left, freshly gather’d, on their native bank. M. Arnold, /Sohrab and Rustum/. PREFACE The purpose of this book is to present a complete collection, subject to certain definitions and exceptions which will be mentioned later, of all the best extant Greek Epigrams. Although many epigrams not given here have in different ways a special interest of their own, none, it is hoped, have been excluded which are of the first excellence in any style. But, while it would be easy to agree on three-fourths of the matter to be included in such a scope, perhaps hardly any two persons would be in exact accordance with regard to the rest; with many pieces which lie on the border line of excellence, the decision must be made on a balance of very slight considerations, and becomes in the end one rather of personal taste than of any fixed principle. For the Greek Anthology proper, use has chiefly been made of the two ∗PDF created by pdfbooks.co.za 1 great works of Jacobs,