Pseudo-Apollodoros' Bibliotheke and the Greek Mythological Tradition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Hellenic Saga Gaia (Earth)

The Hellenic Saga Gaia (Earth) Uranus (Heaven) Oceanus = Tethys Iapetus (Titan) = Clymene Themis Atlas Menoetius Prometheus Epimetheus = Pandora Prometheus • “Prometheus made humans out of earth and water, and he also gave them fire…” (Apollodorus Library 1.7.1) • … “and scatter-brained Epimetheus from the first was a mischief to men who eat bread; for it was he who first took of Zeus the woman, the maiden whom he had formed” (Hesiod Theogony ca. 509) Prometheus and Zeus • Zeus concealed the secret of life • Trick of the meat and fat • Zeus concealed fire • Prometheus stole it and gave it to man • Freidrich H. Fuger, 1751 - 1818 • Zeus ordered the creation of Pandora • Zeus chained Prometheus to a mountain • The accounts here are many and confused Maxfield Parish Prometheus 1919 Prometheus Chained Dirck van Baburen 1594 - 1624 Prometheus Nicolas-Sébastien Adam 1705 - 1778 Frankenstein: The Modern Prometheus • Novel by Mary Shelly • First published in 1818. • The first true Science Fiction novel • Victor Frankenstein is Prometheus • As with the story of Prometheus, the novel asks about cause and effect, and about responsibility. • Is man accountable for his creations? • Is God? • Are there moral, ethical constraints on man’s creative urges? Mary Shelly • “I saw the pale student of unhallowed arts kneeling beside the thing he had put together. I saw the hideous phantasm of a man stretched out, and then, on the working of some powerful engine, show signs of life, and stir with an uneasy, half vital motion. Frightful must it be; for supremely frightful would be the effect of any human endeavour to mock the stupendous mechanism of the Creator of the world” (Introduction to the 1831 edition) Did I request thee, from my clay To mould me man? Did I solicit thee From darkness to promote me? John Milton, Paradise Lost 10. -

OVID Metamorphoses

Metamorphoses Ovid, Joseph D. Reed, Rolfe Humphries Published by Indiana University Press Ovid, et al. Metamorphoses: The New, Annotated Edition. Indiana University Press, 2018. Project MUSE. muse.jhu.edu/book/58757. https://muse.jhu.edu/. For additional information about this book https://muse.jhu.edu/book/58757 [ Access provided at 20 May 2021 05:17 GMT from University of Washington @ Seattle ] book FIve The Fighting of Perseus* So Perseus told his story, and the halls Buzzed loud, not with the cheery noise that rings From floor to rafter at a wedding-party. No; this meant trouble. It was like the riot When sudden squalls lash peaceful waves to surges. Phineus was the reckless one to start it, That warfare, brandishing his spear of ash With sharp bronze point. “Look at me! Here I am,” He cried, “Avenger of my stolen bride! No wings will save you from me, and no god Turned into lying gold.”* He poised the spear, As Cepheus shouted: “Are you crazy, brother? What are you doing? Is this our gratitude, This our repayment for a maiden saved? If truth is what you want, it was not Perseus Who took her from you, but the Nereids Whose power is terrible, it was hornèd Ammon, It was that horrible monster from the ocean Who had to feed on my own flesh and blood, And that was when you really lost her, brother; 107 lines 20–47 She would have died—can your heart be so cruel To wish it so, to heal its grief by causing Grief in my heart? It was not enough, I take it, For you to see her bound and never help her, Never so much as lift a little finger, And you her uncle and her promised husband! So now you grieve that someone else did save her, You covet his reward, a prize so precious, It seems, you could not force yourself to take it From the rocks where it was bound. -

Chronique Archéologique De La Religion Grecque (Chronarg)

Kernos Revue internationale et pluridisciplinaire de religion grecque antique 29 | 2016 Varia Chronique archéologique de la religion grecque (ChronARG) Alain Duplouy, Valeria Tosti, Kalliopi Chatzinikolaou, Michael Fowler, Emmanuel Voutiras, Thierry Petit, Ilaria Battiloro, Massimo Osanna, Nicola Cucuzza et Alexis D’Hautcourt Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/kernos/2403 DOI : 10.4000/kernos.2403 ISSN : 2034-7871 Éditeur Centre international d'étude de la religion grecque antique Édition imprimée Date de publication : 1 octobre 2016 Pagination : 317-390 ISSN : 0776-3824 Référence électronique Alain Duplouy, Valeria Tosti, Kalliopi Chatzinikolaou, Michael Fowler, Emmanuel Voutiras, Thierry Petit, Ilaria Battiloro, Massimo Osanna, Nicola Cucuzza et Alexis D’Hautcourt, « Chronique archéologique de la religion grecque (ChronARG) », Kernos [En ligne], 29 | 2016, mis en ligne le 25 novembre 2018, consulté le 17 novembre 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/kernos/2403 ; DOI : https:// doi.org/10.4000/kernos.2403 Ce document a été généré automatiquement le 17 novembre 2020. Kernos Chronique archéologique de la religion grecque (ChronARG) 1 Chronique archéologique de la religion grecque (ChronARG) Alain Duplouy, Valeria Tosti, Kalliopi Chatzinikolaou, Michael Fowler, Emmanuel Voutiras, Thierry Petit, Ilaria Battiloro, Massimo Osanna, Nicola Cucuzza et Alexis D’Hautcourt [01. Athènes, Attique, Mégaride] 02. Péloponnèse (DESPINA Chatzivasiliou, ALAIN Duplouy ET VALERIA Tosti) Généralités 1 02.01 – A. Bertelli porte un regard critique sur le travail de B. von Mangoldt consacré aux lieux de culte héroïque d’époque classique et hellénistique en Grèce. Parmi les lieux de culte discutés, le Péloponnèse figure en bonne place, notamment l’herôon du carrefour à Corinthe, l’herôon delta de Messène ou le Pélopion d’Olympie. -

Champions of the Gods

Champions of the Gods Champions of the Gods by Warren Merrifield 1 Champions of the Gods Copyright ©2006 Warren Merrifield. This is an entry into the Iron Game Chef ‘06 competition. It uses the ingredients Ancient, Committee and Emotion, and is designed to be played in four two–hour sessions. Typeset in Garamond and Copperplate. Created with Apple Pages software on a G5 iMac. Contact me at [email protected] 2 Champions of the Gods Map of the Ancient Greek World 3 Champions of the Gods Introduction This is my Iron Game Chef ‘06 Entry. It uses the ingredients Ancient, Committee and Emotion, and is designed to be run in four two–hour sessions with between three and five participants. There is no Gamesmaster. I am no authority on Ancient Greece and its myths, so please indulge me any inaccuracies that I may have presented here. Background The Ancient Greek World, during the Age of Gods and Men: Zeus, father of all the Gods has decided that he wants a new religious festival for the Mortals to honour him. He has declared that it will be known as the “Olympics” and shall be held in the most worthy city–state in all of the Greek World — anywhere from Iberia to the Black Sea. But there are more city–states than Zeus can be bothered to remember, so to discover which is most worthy, he has chosen a number of his Godly offspring to do it for him. They will be known as the “Mount Olympus Committee”, and will report back in four mortal years, or Zeus shall rip all of Creation asunder. -

Manual of Mythology

^93 t.i CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY GIFT OF HENRY BEZIAT IN MEMORY OF ANDRE AND KATE BRADLEY BEZIAT 1944 Cornell University Library BL310 .M98 1893 and Rom No Manual of mythology. Greek « Cornell University S Library The original of this book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924029075542 'f' liiiiiliilM^^ ^ M^ISTU^L MYTHOLOGY: GREEK AND ROMAN, NORSE, AND OLD GERMAN, HINDOO AND EGYPTIAN MYTHOLOGY. BY ALEXANDER S. MURRAY, DEPARTMENT OF GREEK AND ROMAN ANTIQUITIES, BRITISH MUSEUM- REPRINTED FROM THE SECOND REVISED LONDON EDITION. •WITH 45 PLATES ON TINTED PAPER, REPRESENTING MORE THAN 90 MYTHOLOGICAL SUBJECTS. NEW YORK: CHARLES SCRIBNER'S SONS, 1893. ; PUBLISHERS' NOTE. Murray's Manual of Mythology has been known to the American public thus far only through the English edition. As originally published, the work was deficient in its account of the Eastern and Northern Mythology; but with these imperfections it secured a sale in this country which proved that it more nearly supplied the want which had long been felt of a compact hand-book in this study than did any other similar work. The preface to the second English edition indicates the important additions to, and changes which have been made in, the original work. Chapters upon the North- ern and Eastern Mythology have been supplied ; the descrip- tions of many of the Greek deities have been re-written accounts of the most memorable works of art, in which each deity is or was represented, have been added ; and a number iii IV PUBLISHERS NOTE. -

Ms. Legrange's Lesson Plans

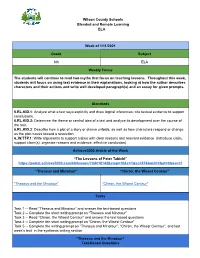

Wilson County Schools Blended and Remote Learning ELA Week of 1/11/2021 Grade Subject 6th ELA Weekly Focus The students will continue to read two myths that focus on teaching lessons. Throughout this week, students will focus on using text evidence in their explanations, looking at how the author describes characters and their actions and write well developed paragraph(s) and an essay for given prompts. Standards 6.RL.KID.1: Analyze what a text says explicitly and draw logical inferences; cite textual evidence to support conclusions. 6.RL.KID.2: Determine the theme or central idea of a text and analyze its development over the course of the text. 6.RL.KID.3: Describe how a plot of a story or drama unfolds, as well as how characters respond or change as the plot moves toward a resolution. 6..W.TTP.1 : Write arguments to support claims with clear reasons and relevant evidence (introduce claim, support claim(s), organize reasons and evidence, effective conclusion). Achieve3000 Article of the Week “The Lessons of Peter Tabichi” https://portal.achieve3000.com/kb/lesson/?lid=18142&step=10&c=1&sc=276&oid=0&ot=0&asn=1 “Theseus and Minotaur” “Chiron, the Wisest Centaur” "Theseus and the Minotaur" "Chiron, the Wisest Centaur" Tasks Task 1 -- Read “Theseus and Minotaur” and answer the text-based questions Task 2 -- Complete the short writing prompt on “Theseus and Minotaur” Task 3 -- Read ”Chiron, the Wisest Centaur” and answer the text-based questions Task 4 -- Complete the short writing prompt on “Chiron, the Wisest Centaur” Task 5 -- Complete the writing prompt on “Theseus and Minotaur”, “Chiron, the Wisest Centaur”, and last week’s text in the synthesis writing section. -

Sons and Fathers in the Catalogue of Argonauts in Apollonius Argonautica 1.23-233

Sons and fathers in the catalogue of Argonauts in Apollonius Argonautica 1.23-233 ANNETTE HARDER University of Groningen [email protected] 1. Generations of heroes The Argonautica of Apollonius Rhodius brings emphatically to the attention of its readers the distinction between the generation of the Argonauts and the heroes of the Trojan War in the next genera- tion. Apollonius initially highlights this emphasis in the episode of the Argonauts’ departure, when the baby Achilles is watching them, at AR 1.557-5581 σὺν καί οἱ (sc. Chiron) παράκοιτις ἐπωλένιον φορέουσα | Πηλείδην Ἀχιλῆα, φίλωι δειδίσκετο πατρί (“and with him his wife, hold- ing Peleus’ son Achilles in her arms, showed him to his dear father”)2; he does so again in 4.866-879, which describes Thetis and Achilles as a baby. Accordingly, several scholars have focused on the ways in which 1 — On this marker of the generations see also Klooster 2014, 527. 2 — All translations of Apollonius are by Race 2008. EuGeStA - n°9 - 2019 2 ANNETTE HARDER Apollonius has avoided anachronisms by carefully distinguishing between the Argonauts and the heroes of the Trojan War3. More specifically Jacqueline Klooster (2014, 521-530), in discussing the treatment of time in the Argonautica, distinguishes four periods of time to which Apollonius refers: first, the time before the Argo sailed, from the beginning of the cosmos (featured in the song of Orpheus in AR 1.496-511); second, the time of its sailing (i.e. the time of the epic’s setting); third, the past after the Argo sailed and fourth the present inhab- ited by the narrator (both hinted at by numerous allusions and aitia). -

Flowers in Greek Mythology

Flowers in Greek Mythology Everybody knows how rich and exciting Greek Mythology is. Everybody also knows how rich and exciting Greek Flora is. Find out some of the famous Greek myths flower inspired. Find out how feelings and passions were mixed together with flowers to make wonderful stories still famous in nowadays. Anemone:The name of the plant is directly linked to the well known ancient erotic myth of Adonis and Aphrodite (Venus). It has been inspired great poets like Ovidius or, much later, Shakespeare, to compose hymns dedicated to love. According to this myth, while Adonis was hunting in the forest, the ex- lover of Aphrodite, Ares, disguised himself as a wild boar and attacked Adonis causing him lethal injuries. Aphrodite heard the groans of Adonis and rushed to him, but it was too late. Aphrodite got in her arms the lifeless body of her beloved Adonis and it is said the she used nectar in order to spray the wood. The mixture of the nectar and blood sprang a beautiful flower. However, the life of this 1 beautiful flower doesn’t not last. When the wind blows, makes the buds of the plant to bloom and then drifted away. This flower is called Anemone because the wind helps the flowering and its decline. Adonis:It would be an omission if we do not mention that there is a flower named Adonis, which has medicinal properties. According to the myth, this flower is familiar to us as poppy meadows with the beautiful red colour. (Adonis blood). Iris: The flower got its name from the Greek goddess Iris, goddess of the rainbow. -

1 Divine Intervention and Disguise in Homer's Iliad Senior Thesis

Divine Intervention and Disguise in Homer’s Iliad Senior Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Undergraduate School of Arts and Sciences Brandeis University Undergraduate Program in Classical Studies Professor Joel Christensen, Advisor In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts By Joana Jankulla May 2018 Copyright by Joana Jankulla 1 Copyright by Joana Jankulla © 2018 2 Acknowledgements First and foremost, I would like to thank my advisor, Professor Joel Christensen. Thank you, Professor Christensen for guiding me through this process, expressing confidence in me, and being available whenever I had any questions or concerns. I would not have been able to complete this work without you. Secondly, I would like to thank Professor Ann Olga Koloski-Ostrow and Professor Cheryl Walker for reading my thesis and providing me with feedback. The Classics Department at Brandeis University has been an instrumental part of my growth in my four years as an undergraduate, and I am eternally thankful to all the professors and staff members in the department. Thank you to my friends, specifically Erica Theroux, Sarah Jousset, Anna Craven, Rachel Goldstein, Taylor McKinnon and Georgie Contreras for providing me with a lot of emotional support this year. I hope you all know how grateful I am for you as friends and how much I have appreciated your love this year. Thank you to my mom for FaceTiming me every time I was stressed about completing my thesis and encouraging me every step of the way. Finally, thank you to Ian Leeds for dropping everything and coming to me each time I needed it. -

Studies in Early Mediterranean Poetics and Cosmology

The Ruins of Paradise: Studies in Early Mediterranean Poetics and Cosmology by Matthew M. Newman A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Classical Studies) in the University of Michigan 2015 Doctoral Committee: Professor Richard Janko, Chair Professor Sara L. Ahbel-Rappe Professor Gary M. Beckman Associate Professor Benjamin W. Fortson Professor Ruth S. Scodel Bind us in time, O Seasons clear, and awe. O minstrel galleons of Carib fire, Bequeath us to no earthly shore until Is answered in the vortex of our grave The seal’s wide spindrift gaze toward paradise. (from Hart Crane’s Voyages, II) For Mom and Dad ii Acknowledgments I fear that what follows this preface will appear quite like one of the disorderly monsters it investigates. But should you find anything in this work compelling on account of its being lucid, know that I am not responsible. Not long ago, you see, I was brought up on charges of obscurantisme, although the only “terroristic” aspects of it were self- directed—“Vous avez mal compris; vous êtes idiot.”1 But I’ve been rehabilitated, or perhaps, like Aphrodite in Iliad 5 (if you buy my reading), habilitated for the first time, to the joys of clearer prose. My committee is responsible for this, especially my chair Richard Janko and he who first intervened, Benjamin Fortson. I thank them. If something in here should appear refined, again this is likely owing to the good taste of my committee. And if something should appear peculiarly sensitive, empathic even, then it was the humanity of my committee that enabled, or at least amplified, this, too. -

Cultural Sightseeing

SIGHTSEEING IN CRETA A QUICK GUIDE TO INTERESTING PLACES WORTH VISIT SUMMER 2020 KNOSSOS The archaeological site of Knossos (Knosós GR: Κνωσός) is sited 5 km southeast of the city of Iraklion. There is evidence that this location was inhabited during the neolithic times (6000 B.C.). On the ruins of the neolithic settlement was built the first Minoan palace (1900 B.C.) where the dynasty of Minos ruled. This was destroyed in 1700 B.C and a new palace built in its place. The palace covered an area of 22,000sq.m, it was multi- storeyed and had an intricate plan. Due to this fact the Palace is connected with thrilling legends, such as the myth of the Labyrinth with the Minotaur. Between 1.700-1.450 BC, the Minoan civilization was at its peak and Knossos was the most important city-state. During these years the city was destroyed twice by earthquakes (1.600 BC, 1.450 BC) and rebuilt. The city of Knossos had 100.000 citizens and it continued to be an important city-state until the early Byzantine period. Knossos gave birth to famous men like Hersifron and his son Metagenis, whose creation was the temple of Artemis in Efesos, the Artemisio, one of the seven wonders of the ancient world. THE MINOAN PALACE AND CITY OF MALIA The Minoan Palace and the archaeological site of Malia are located 3 km East of the town of Malia. From the architectural point of view the Palace of Malia, is the third- largest of the Minoan Palaces and is considered the most "provincial" of them. -

The 'Trial by Water' in Greek Myth and Literature

Leeds International Classical Studies 7.1 (2008) ISSN 1477-3643 (http://www.leeds.ac.uk/classics/lics/) © Fiona McHardy The ‘trial by water’ in Greek myth and literature FIONA MCHARDY (ROEHAMPTON UNIVERSITY) ABSTRACT: This paper discusses the theme of casting ‘unchaste’ women into the sea as a punishment in Greek myth and literature. Particular focus will be given to the stories of Danaë, Augë, Aerope and Phronime, who are all depicted suffering this punishment at the hands of their fathers. While Seaford (1990) has emphasized the theme of imprisonment which occurs in some of the stories involving the ‘floating chest’, I turn my attention instead to the theme of the sea. The coincidence in these stories of the threat of drowning for apparent promiscuity or sexual impurity with the escape of those girls who are innocent can be explained by the phenomenon of the ‘trial by water’ as evidenced in Babylonian and other early law codes (cf. Glotz 1904). Further evidence for this theory can be found in ancient novels where the trial of the heroine for sexual purity is often a key theme. The significance of chastity in the myths and in Athenian society is central to understanding the story patterns. The interrelationship of mythic and social ideals is drawn out in the paper. This paper examines the punishment of ‘unchaste’ women in Greek myth and literature, in particular their representation in Euripides’ fragmentary Augë, Cretan Women and Danaë. My focus is on punishments involving the sea, where it is possible to discern two interrelated strands in the tales.1 The first strand involves an angry parent condemning an errant daughter to be cast into the sea with the intention of drowning her.