Studies on Homer and the Homeric Age, Vol. 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Hellenic Saga Gaia (Earth)

The Hellenic Saga Gaia (Earth) Uranus (Heaven) Oceanus = Tethys Iapetus (Titan) = Clymene Themis Atlas Menoetius Prometheus Epimetheus = Pandora Prometheus • “Prometheus made humans out of earth and water, and he also gave them fire…” (Apollodorus Library 1.7.1) • … “and scatter-brained Epimetheus from the first was a mischief to men who eat bread; for it was he who first took of Zeus the woman, the maiden whom he had formed” (Hesiod Theogony ca. 509) Prometheus and Zeus • Zeus concealed the secret of life • Trick of the meat and fat • Zeus concealed fire • Prometheus stole it and gave it to man • Freidrich H. Fuger, 1751 - 1818 • Zeus ordered the creation of Pandora • Zeus chained Prometheus to a mountain • The accounts here are many and confused Maxfield Parish Prometheus 1919 Prometheus Chained Dirck van Baburen 1594 - 1624 Prometheus Nicolas-Sébastien Adam 1705 - 1778 Frankenstein: The Modern Prometheus • Novel by Mary Shelly • First published in 1818. • The first true Science Fiction novel • Victor Frankenstein is Prometheus • As with the story of Prometheus, the novel asks about cause and effect, and about responsibility. • Is man accountable for his creations? • Is God? • Are there moral, ethical constraints on man’s creative urges? Mary Shelly • “I saw the pale student of unhallowed arts kneeling beside the thing he had put together. I saw the hideous phantasm of a man stretched out, and then, on the working of some powerful engine, show signs of life, and stir with an uneasy, half vital motion. Frightful must it be; for supremely frightful would be the effect of any human endeavour to mock the stupendous mechanism of the Creator of the world” (Introduction to the 1831 edition) Did I request thee, from my clay To mould me man? Did I solicit thee From darkness to promote me? John Milton, Paradise Lost 10. -

Sample Odyssey Passage

The Odyssey of Homer Translated from Greek into English prose in 1879 by S.H. Butcher and Andrew Lang. Book I In a Council of the Gods, Poseidon absent, Pallas procureth an order for the restitution of Odysseus; and appearing to his son Telemachus, in human shape, adviseth him to complain of the Wooers before the Council of the people, and then go to Pylos and Sparta to inquire about his father. Tell me, Muse, of that man, so ready at need, who wandered far and wide, after he had sacked the sacred citadel of Troy, and many were the men whose towns he saw and whose mind he learnt, yea, and many the woes he suffered in his heart upon the deep, striving to win his own life and the return of his company. Nay, but even so he saved not his company, though he desired it sore. For through the blindness of their own hearts they perished, fools, who devoured the oxen of Helios Hyperion: but the god took from them their day of returning. Of these things, goddess, daughter of Zeus, whencesoever thou hast heard thereof, declare thou even unto us. Now all the rest, as many as fled from sheer destruction, were at home, and had escaped both war and sea, but Odysseus only, craving for his wife and for his homeward path, the lady nymph Calypso held, that fair goddess, in her hollow caves, longing to have him for her lord. But when now the year had come in the courses of the seasons, wherein the gods had ordained that he should return home to Ithaca, not even there was he quit of labours, not even among his own; but all the gods had pity on him save Poseidon, who raged continually against godlike Odysseus, till he came to his own country. -

Rejuvenations and Satyricons of Yesterday

REJUVENATIONS AND SATYRICONS OF YESTERDAY By PAN. S. CODELLAS, M.D. SAN FRANCISCO Whence and Whithe r ? and hard labour and exhausting diseases, HEN the grey matter in which the Fates give to men; they lived the human cortex began to like Gods with a soul not touched by sorrow, far away from labour and grief; develop and establish sen- there was no miserable senility; for always sation, perception, emo- the arms and legs were strong and inde- tions, instinctive, purposefulfatigable, or ra - enjoying merry feasts beyond tionalW reactions towards a desired the reach of all evils. They died as if they objective, association, memory, gen- were subdued into sleep.” [Hesiod’s eral intelligence, judgment, then man “Works and Days,” 90 seq.] began to realize environment and attempt to control it. The early man Impos ition of Death in his later intellectual infancy prob- ably was imbued with the curiosity Death was the subject of numerous to answer the question of the origin speculations as to its origin. Among of his earthly appearance and dis- the earliest primitive theories we appearance, of Life and Death. find it commonly thought to be a To primitive intellect human in- trick. At a later period it appears itium and exitus were not two op- to be due to the malevolence of posing ends as they are to maturing demons craving human flesh and for more advanced mind. this inflicting death to men. To some The earliest men thought of life death was the separation of the soul as a natural, normal condition, be- from the body, which was the result cause they realized by it in the male of sorcery. -

Early Theories of Foreignness (Kennedy, RECW Ch 1 Pp

Clas 122 2017 Mon Oct 2: Homer and Hesiod: Early Theories of Foreignness (Kennedy, RECW Ch 1 pp. 3-13) Overview of Homer's Odyssey -- a map of the world imagined by speakers of Greek The poem itself invites its audience to think about: What is a good society? What is a good leader? As readers here and now, we can also ask critical Questions: What are the poem's blind spots? How does the poem encourage its audience to think and behave? Do the poem's ideas about a good society and a good leader have meaning today? The images below come from a series of collages and paintings by Romare Bearden (1911-1988). The Smithsonian Institution organized a bautiful exhibit of the series recently, and there is a good free app (showing many of the works and adding audio commentary) available for I phone and android; search for "A Black Odyssey" where you get apps. As our story begins ..... During his journey back to his home in Ithaca after the war at Troy, Odysseus is on the island of Calypso. Athena asks Zeus if Odysseus can come home to Ithaca. Zeus says yes, and sends Hermes to tell Calypso that Odysseus needs to come home. Calypso lets Odysseus build a raft and he departs. This is only possible because .... RECW 1.1 Od. 1.22-26: Poseidon, the god of the sea, is visiting the Ethiopians, and thus is not watching Odysseus. Poseidon had been thwarting the homecoming because of the way that Odysseus treated the Cyclops Polyphemus, who was descended from Poseidon. -

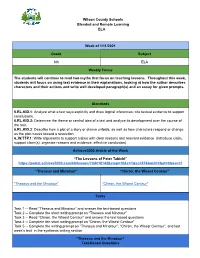

Ms. Legrange's Lesson Plans

Wilson County Schools Blended and Remote Learning ELA Week of 1/11/2021 Grade Subject 6th ELA Weekly Focus The students will continue to read two myths that focus on teaching lessons. Throughout this week, students will focus on using text evidence in their explanations, looking at how the author describes characters and their actions and write well developed paragraph(s) and an essay for given prompts. Standards 6.RL.KID.1: Analyze what a text says explicitly and draw logical inferences; cite textual evidence to support conclusions. 6.RL.KID.2: Determine the theme or central idea of a text and analyze its development over the course of the text. 6.RL.KID.3: Describe how a plot of a story or drama unfolds, as well as how characters respond or change as the plot moves toward a resolution. 6..W.TTP.1 : Write arguments to support claims with clear reasons and relevant evidence (introduce claim, support claim(s), organize reasons and evidence, effective conclusion). Achieve3000 Article of the Week “The Lessons of Peter Tabichi” https://portal.achieve3000.com/kb/lesson/?lid=18142&step=10&c=1&sc=276&oid=0&ot=0&asn=1 “Theseus and Minotaur” “Chiron, the Wisest Centaur” "Theseus and the Minotaur" "Chiron, the Wisest Centaur" Tasks Task 1 -- Read “Theseus and Minotaur” and answer the text-based questions Task 2 -- Complete the short writing prompt on “Theseus and Minotaur” Task 3 -- Read ”Chiron, the Wisest Centaur” and answer the text-based questions Task 4 -- Complete the short writing prompt on “Chiron, the Wisest Centaur” Task 5 -- Complete the writing prompt on “Theseus and Minotaur”, “Chiron, the Wisest Centaur”, and last week’s text in the synthesis writing section. -

Iliad Teacher Sample

CONTENTS Teaching Guidelines ...................................................4 Appendix Book 1: The Anger of Achilles ...................................6 Genealogies ...............................................................57 Book 2: Before Battle ................................................8 Alternate Names in Homer’s Iliad ..............................58 Book 3: Dueling .........................................................10 The Friends and Foes of Homer’s Iliad ......................59 Book 4: From Truce to War ........................................12 Weaponry and Armor in Homer..................................61 Book 5: Diomed’s Day ...............................................14 Ship Terminology in Homer .......................................63 Book 6: Tides of War .................................................16 Character References in the Iliad ...............................65 Book 7: A Duel, a Truce, a Wall .................................18 Iliad Tests & Keys .....................................................67 Book 8: Zeus Takes Charge ........................................20 Book 9: Agamemnon’s Day ........................................22 Book 10: Spies ...........................................................24 Book 11: The Wounded ..............................................26 Book 12: Breach ........................................................28 Book 13: Tug of War ..................................................30 Book 14: Return to the Fray .......................................32 -

The Birds and Plato's Symposium.Pdf

Baquerizo 1 Olivia M. Baquerizo ([email protected]) CAMWS 2021, Plato Panel Fordham Univeristy Friday, April 9 Aetiologies of Eros: The Birds and Plato’s Symposium abstract: https://camws.org/sites/default/files/meeting2021/abstracts/2389AetiologiesofEros.pdf Ephialtes and Otus in the Platonic Aristophanes’ Speech 1. Ephialtes and Otus in the Symposium (190b.5-190c) trans. Nehamas and Woodruff ἦν οὖν τὴν ἰσχὺν δεινὰ καὶ τὴν ῥώμην, καὶ τὰ In strength and power, therefore, they were φρονήματα μεγάλα εἶχον, ἐπεχείρησαν δὲ τοῖς θεοῖς, terrible, and they had great ambitions. They καὶ ὃ λέγει Ὅμηρος περὶ Ἐφιάλτου τε καὶ Ὤτου, περὶ made an attempt on the gods, and homer’s ἐκείνων λέγεται, τὸ εἰς τὸν οὐρανὸν ἀνάβασιν story about Ephiatles and Otus was ἐπιχειρεῖν ποιεῖν, ὡς ἐπιθησομένων τοῖς θεοῖς originally about them: how they tried to make an ascent to heaven so as to attack the gods. 2. Ephialtes and Otus in the Odyssey (11.306-20) trans. A. S. kline τὴν δὲ μετ᾽ Ἰφιμέδειαν, Ἀλωῆος παράκοιτιν Next I saw Iphimedeia, Aloeus’ wife, who εἴσιδον, ἣ δὴ φάσκε Ποσειδάωνι μιγῆναι, claimed she had slept with Poseidon. She καί ῥ᾽ ἔτεκεν δύο παῖδε, μινυνθαδίω δ᾽ ἐγενέσθην, too bore twins, short-lived, godlike Otus and Ὦτόν τ᾽ ἀντίθεον τηλεκλειτόν τ᾽ Ἐφιάλτην, famous Ephialtes, the tallest most handsome οὓς δὴ μηκίστους θρέψε ζείδωρος ἄρουρα men by far, bar great Orion, whom the καὶ πολὺ καλλίστους μετά γε κλυτὸν Ὠρίωνα: 310 fertile Earth ever nourished. They were ἐννέωροι γὰρ τοί γε καὶ ἐννεαπήχεες ἦσαν fifteen feet wide, and fifty feet high at nine εὖρος, ἀτὰρ μῆκός γε γενέσθην ἐννεόργυιοι. -

Greek and Roman Mythology and Heroic Legend

G RE E K AN D ROMAN M YTH O LOGY AN D H E R O I C LE GEN D By E D I N P ROFES SOR H . ST U G Translated from th e German and edited b y A M D i . A D TT . L tt LI ONEL B RN E , , TRANSLATOR’S PREFACE S Y a l TUD of Greek religion needs no po ogy , and should This mus v n need no bush . all t feel who ha e looked upo the ns ns and n creatio of the art it i pired . But to purify stre gthen admiration by the higher light of knowledge is no work o f ea se . No truth is more vital than the seemi ng paradox whi c h - declares that Greek myths are not nature myths . The ape - is not further removed from the man than is the nature myth from the religious fancy of the Greeks as we meet them in s Greek is and hi tory . The myth the child of the devout lovely imagi nation o f the noble rac e that dwelt around the e e s n s s u s A ga an. Coar e fa ta ie of br ti h forefathers in their Northern homes softened beneath the southern sun into a pure and u and s godly bea ty, thus gave birth to the divine form of n Hellenic religio . M c an c u s m c an s Comparative ythology tea h uch . It hew how god s are born in the mind o f the savage and moulded c nn into his image . -

Magical Practice in the Latin West Religions in the Graeco-Roman World

Magical Practice in the Latin West Religions in the Graeco-Roman World Editors H.S. Versnel D. Frankfurter J. Hahn VOLUME 168 Magical Practice in the Latin West Papers from the International Conference held at the University of Zaragoza 30 Sept.–1 Oct. 2005 Edited by Richard L. Gordon and Francisco Marco Simón LEIDEN • BOSTON 2010 Th is book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Magical practice in the Latin West : papers from the international conference held at the University of Zaragoza, 30 Sept.–1 Oct. 2005 / edited by Richard L. Gordon and Francisco Marco Simon. p. cm. — (Religions in the Graeco-Roman world, ISSN 0927-7633 ; v. 168) Includes indexes. ISBN 978-90-04-17904-2 (hardback : alk. paper) 1. Magic—Europe—History— Congresses. I. Gordon, R. L. (Richard Lindsay) II. Marco Simón, Francisco. III. Title. IV. Series. BF1591.M3444 2010 133.4’3094—dc22 2009041611 ISSN 0927-7633 ISBN 978 90 04 17904 2 Copyright 2010 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, Th e Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill, Hotei Publishing, IDC Publishers, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers and VSP. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by Koninklijke Brill NV provided that the appropriate fees are paid directly to Th e Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Suite 910, Danvers, MA 01923, USA. -

1 Divine Intervention and Disguise in Homer's Iliad Senior Thesis

Divine Intervention and Disguise in Homer’s Iliad Senior Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Undergraduate School of Arts and Sciences Brandeis University Undergraduate Program in Classical Studies Professor Joel Christensen, Advisor In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts By Joana Jankulla May 2018 Copyright by Joana Jankulla 1 Copyright by Joana Jankulla © 2018 2 Acknowledgements First and foremost, I would like to thank my advisor, Professor Joel Christensen. Thank you, Professor Christensen for guiding me through this process, expressing confidence in me, and being available whenever I had any questions or concerns. I would not have been able to complete this work without you. Secondly, I would like to thank Professor Ann Olga Koloski-Ostrow and Professor Cheryl Walker for reading my thesis and providing me with feedback. The Classics Department at Brandeis University has been an instrumental part of my growth in my four years as an undergraduate, and I am eternally thankful to all the professors and staff members in the department. Thank you to my friends, specifically Erica Theroux, Sarah Jousset, Anna Craven, Rachel Goldstein, Taylor McKinnon and Georgie Contreras for providing me with a lot of emotional support this year. I hope you all know how grateful I am for you as friends and how much I have appreciated your love this year. Thank you to my mom for FaceTiming me every time I was stressed about completing my thesis and encouraging me every step of the way. Finally, thank you to Ian Leeds for dropping everything and coming to me each time I needed it. -

Studies in Early Mediterranean Poetics and Cosmology

The Ruins of Paradise: Studies in Early Mediterranean Poetics and Cosmology by Matthew M. Newman A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Classical Studies) in the University of Michigan 2015 Doctoral Committee: Professor Richard Janko, Chair Professor Sara L. Ahbel-Rappe Professor Gary M. Beckman Associate Professor Benjamin W. Fortson Professor Ruth S. Scodel Bind us in time, O Seasons clear, and awe. O minstrel galleons of Carib fire, Bequeath us to no earthly shore until Is answered in the vortex of our grave The seal’s wide spindrift gaze toward paradise. (from Hart Crane’s Voyages, II) For Mom and Dad ii Acknowledgments I fear that what follows this preface will appear quite like one of the disorderly monsters it investigates. But should you find anything in this work compelling on account of its being lucid, know that I am not responsible. Not long ago, you see, I was brought up on charges of obscurantisme, although the only “terroristic” aspects of it were self- directed—“Vous avez mal compris; vous êtes idiot.”1 But I’ve been rehabilitated, or perhaps, like Aphrodite in Iliad 5 (if you buy my reading), habilitated for the first time, to the joys of clearer prose. My committee is responsible for this, especially my chair Richard Janko and he who first intervened, Benjamin Fortson. I thank them. If something in here should appear refined, again this is likely owing to the good taste of my committee. And if something should appear peculiarly sensitive, empathic even, then it was the humanity of my committee that enabled, or at least amplified, this, too. -

Myth, the Marvelous, the Exotic, and the Hero in the Roman D'alexandre

Myth, the Marvelous, the Exotic, and the Hero in the Roman d’Alexandre Paul Henri Rogers A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Romance Languages (French) Chapel Hill 2008 Approved by: Dr. Edward D. Montgomery Dr. Frank A. Domínguez Dr. Edward D. Kennedy Dr. Hassan Melehy Dr. Monica P. Rector © 2008 Paul Henri Rogers ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii Abstract Paul Henri Rogers Myth, the Marvelous, the Exotic, and the Hero in the Roman d’Alexandre Under the direction of Dr. Edward D. Montgomery In the Roman d’Alexandre , Alexandre de Paris generates new myth by depicting Alexander the Great as willfully seeking to inscribe himself and his deeds within the extant mythical tradition, and as deliberately rivaling the divine authority. The contemporary literary tradition based on Quintus Curtius’s Gesta Alexandri Magni of which Alexandre de Paris may have been aware eliminates many of the marvelous episodes of the king’s life but focuses instead on Alexander’s conquests and drive to compete with the gods’ accomplishments. The depiction of his premature death within this work and the Roman raises the question of whether or not an individual can actively seek deification. Heroic figures are at the origin of divinity and myth, and the Roman d’Alexandre portrays Alexander as an essentially very human character who is nevertheless dispossessed of the powerful attributes normally associated with heroic protagonists.