The Iliad of Homer by Homer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Odyssey Glossary of Names

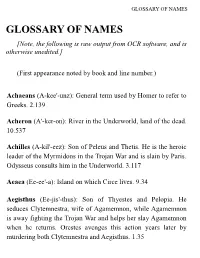

GLOSSARY OF NAMES GLOSSARY OF NAMES [Note, the following is raw output from OCR software, and is otherwise unedited.] (First appearance noted by book and line number.) Achaeans (A-kee'-unz): General term used by Homer to reFer to Greeks. 2.139 Acheron (A'-ker-on): River in the Underworld, land of the dead. 10.537 Achilles (A-kil'-eez): Son of Peleus and Thetis. He is the heroic leader of the Myrmidons in the Trojan War and is slain by Paris. Odysseus consults him in the Underworld. 3.117 Aeaea (Ee-ee'-a): Island on which Circe lives. 9.34 Aegisthus (Ee-jis'-thus): Son of Thyestes and Pelopia. He seduces Clytemnestra, wife of Agamemnon, while Agamemnon is away fighting the Trojan War and helps her slay Agamemnon when he returns. Orestes avenges this action years later by murdering both Clytemnestra and Aegisthus. 1.35 GLOSSARY OF NAMES Aegyptus (Ee-jip'-tus): The Nile River. 4.511 Aeolus (Ee'-oh-lus): King of the island Aeolia and keeper of the winds. 10.2 Aeson (Ee'-son): Son oF Cretheus and Tyro; father of Jason, leader oF the Argonauts. 11.262 Aethon (Ee'-thon): One oF Odysseus' aliases used in his conversation with Penelope. 19.199 Agamemnon (A-ga-mem'-non): Son oF Atreus and Aerope; brother of Menelaus; husband oF Clytemnestra. He commands the Greek Forces in the Trojan War. He is killed by his wiFe and her lover when he returns home; his son, Orestes, avenges this murder. 1.36 Agelaus (A-je-lay'-us): One oF Penelope's suitors; son oF Damastor; killed by Odysseus. -

Sophocles, Ajax, Lines 1-171

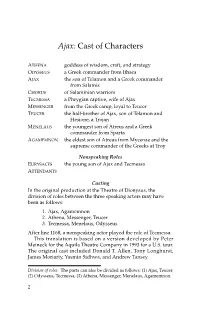

SophoclesFourTrag-00Bk Page 2 Thursday, July 26, 2007 3:56 PM Ajax: Cast of Characters ATHENA goddess of wisdom, craft, and strategy ODYSSEUS a Greek commander from Ithaca AJAX the son of Telamon and a Greek commander from Salamis CHORUS of Salaminian warriors TECMESSA a Phrygian captive, wife of Ajax MESSENGER from the Greek camp, loyal to Teucer TEUCER the half-brother of Ajax, son of Telamon and Hesione, a Trojan MENELAUS the youngest son of Atreus and a Greek commander from Sparta AGAMEMNON the eldest son of Atreus from Mycenae and the supreme commander of the Greeks at Troy Nonspeaking Roles EURYSACES the young son of Ajax and Tecmessa ATTENDANTS Casting In the original production at the Theatre of Dionysus, the division of roles between the three speaking actors may have been as follows: 1. Ajax, Agamemnon 2. Athena, Messenger, Teucer 3. Tecmessa, Menelaus, Odysseus After line 1168, a nonspeaking actor played the role of Tecmessa. This translation is based on a version developed by Peter Meineck for the Aquila Theatre Company in 1993 for a U.S. tour. The original cast included Donald T. Allen, Tony Longhurst, James Moriarty, Yasmin Sidhwa, and Andrew Tansey. Division of roles: The parts can also be divided as follows: (1) Ajax, Teucer; (2) Odysseus, Tecmessa; (3) Athena, Messenger, Menelaus, Agamemnon. 2 SophoclesFourTrag-00Bk Page 3 Thursday, July 26, 2007 3:56 PM Ajax SCENE: Night. The Greek camp at Troy. It is the ninth year of the Trojan War, after the death of Achilles. Odysseus is following tracks that lead him outside the tent of Ajax. -

HOMERIC-ILIAD.Pdf

Homeric Iliad Translated by Samuel Butler Revised by Soo-Young Kim, Kelly McCray, Gregory Nagy, and Timothy Power Contents Rhapsody 1 Rhapsody 2 Rhapsody 3 Rhapsody 4 Rhapsody 5 Rhapsody 6 Rhapsody 7 Rhapsody 8 Rhapsody 9 Rhapsody 10 Rhapsody 11 Rhapsody 12 Rhapsody 13 Rhapsody 14 Rhapsody 15 Rhapsody 16 Rhapsody 17 Rhapsody 18 Rhapsody 19 Rhapsody 20 Rhapsody 21 Rhapsody 22 Rhapsody 23 Rhapsody 24 Homeric Iliad Rhapsody 1 Translated by Samuel Butler Revised by Soo-Young Kim, Kelly McCray, Gregory Nagy, and Timothy Power [1] Anger [mēnis], goddess, sing it, of Achilles, son of Peleus— 2 disastrous [oulomenē] anger that made countless pains [algea] for the Achaeans, 3 and many steadfast lives [psūkhai] it drove down to Hādēs, 4 heroes’ lives, but their bodies it made prizes for dogs [5] and for all birds, and the Will of Zeus was reaching its fulfillment [telos]— 6 sing starting from the point where the two—I now see it—first had a falling out, engaging in strife [eris], 7 I mean, [Agamemnon] the son of Atreus, lord of men, and radiant Achilles. 8 So, which one of the gods was it who impelled the two to fight with each other in strife [eris]? 9 It was [Apollo] the son of Leto and of Zeus. For he [= Apollo], infuriated at the king [= Agamemnon], [10] caused an evil disease to arise throughout the mass of warriors, and the people were getting destroyed, because the son of Atreus had dishonored Khrysēs his priest. Now Khrysēs had come to the ships of the Achaeans to free his daughter, and had brought with him a great ransom [apoina]: moreover he bore in his hand the scepter of Apollo wreathed with a suppliant’s wreath [15] and he besought the Achaeans, but most of all the two sons of Atreus, who were their chiefs. -

JONATHAN FENNO Curriculum Vitae

JONATHAN FENNO Curriculum Vitae SPECIAL INTERESTS Greek and Latin Poetry, Greek Religion, Ancient Athletics, Romans in Cinema DISSERTATION Poet, Athletes, and Heroes: Theban and Aeginetan Identity in Pindar's Aeginetan Odes DEGREES IN CLASSICS 6/1995 Ph.D., UCLA 6/1989 M.A., UCLA 5/1986 B.A. Summa cum Laude, Concordia College, Moorhead, Minnesota ACADEMIC POSITIONS 2009– Associate Professor, University of Mississippi 2002–09 Assistant Professor, University of Mississippi 2002 Adjunct Assistant Professor, Gettysburg College 1999–2001 Assistant Professor, College of Charleston 1996–99 Visiting Assistant Professor, College of Charleston 1995–96 Lecturer, UCLA 1988–95 Teaching Assistant, UCLA ARTICLES PUBLISHED “The Wrath and Vengeance of Swift-Footed Aeneas in Iliad XIII” Phoenix 62 (2008) 145–61 “The Mist Shed by Zeus in Iliad XVII” The Classical Journal 104.1 (2008) 1–9 “‘A Great Wave against the Stream’: Water Imagery in Iliadic Battle Scenes” American Journal of Philology 126.4 (2005) 475–504 “Semonides 7.43: A Hard/Stubborn Ass” Mnemosyne 58.3 (2005) 408–11 “Setting Aright the House of Themistius in Pindar’s Nemean 5 and Isthmian 6” Hermes 133.3 (2005) 294–311 “Praxidamas' Crown and the Omission at Pindar Nemean 6.18” Classical Quarterly 53.2 (2003) 338–46 PAPERS PRESENTED “Typical Heroic Careers and Large-Scale Design in the Iliad” CAMWS 2015 “Odysseus and Hector in the Iliad” CAMWS 2014 “The Schedius Sequence and the Alternating Rhythm of the Iliadic Battle Narrative” CAMWS 2013 “Stretching out the Battle in Equal Portions: An Iliadic -

Archaic Eretria

ARCHAIC ERETRIA This book presents for the first time a history of Eretria during the Archaic Era, the city’s most notable period of political importance. Keith Walker examines all the major elements of the city’s success. One of the key factors explored is Eretria’s role as a pioneer coloniser in both the Levant and the West— its early Aegean ‘island empire’ anticipates that of Athens by more than a century, and Eretrian shipping and trade was similarly widespread. We are shown how the strength of the navy conferred thalassocratic status on the city between 506 and 490 BC, and that the importance of its rowers (Eretria means ‘the rowing city’) probably explains the appearance of its democratic constitution. Walker dates this to the last decade of the sixth century; given the presence of Athenian political exiles there, this may well have provided a model for the later reforms of Kleisthenes in Athens. Eretria’s major, indeed dominant, role in the events of central Greece in the last half of the sixth century, and in the events of the Ionian Revolt to 490, is clearly demonstrated, and the tyranny of Diagoras (c. 538–509), perhaps the golden age of the city, is fully examined. Full documentation of literary, epigraphic and archaeological sources (most of which have previously been inaccessible to an English-speaking audience) is provided, creating a fascinating history and a valuable resource for the Greek historian. Keith Walker is a Research Associate in the Department of Classics, History and Religion at the University of New England, Armidale, Australia. -

Provided by the Internet Classics Archive. See Bottom for Copyright

Provided by The Internet Classics Archive. See bottom for copyright. Available online at http://classics.mit.edu//Homer/iliad.html The Iliad By Homer Translated by Samuel Butler ---------------------------------------------------------------------- BOOK I Sing, O goddess, the anger of Achilles son of Peleus, that brought countless ills upon the Achaeans. Many a brave soul did it send hurrying down to Hades, and many a hero did it yield a prey to dogs and vultures, for so were the counsels of Jove fulfilled from the day on which the son of Atreus, king of men, and great Achilles, first fell out with one another. And which of the gods was it that set them on to quarrel? It was the son of Jove and Leto; for he was angry with the king and sent a pestilence upon the host to plague the people, because the son of Atreus had dishonoured Chryses his priest. Now Chryses had come to the ships of the Achaeans to free his daughter, and had brought with him a great ransom: moreover he bore in his hand the sceptre of Apollo wreathed with a suppliant's wreath and he besought the Achaeans, but most of all the two sons of Atreus, who were their chiefs. "Sons of Atreus," he cried, "and all other Achaeans, may the gods who dwell in Olympus grant you to sack the city of Priam, and to reach your homes in safety; but free my daughter, and accept a ransom for her, in reverence to Apollo, son of Jove." On this the rest of the Achaeans with one voice were for respecting the priest and taking the ransom that he offered; but not so Agamemnon, who spoke fiercely to him and sent him roughly away. -

Dares Phrygius' De Excidio Trojae Historia: Philological Commentary and Translation

Faculteit Letteren & Wijsbegeerte Dares Phrygius' De Excidio Trojae Historia: Philological Commentary and Translation Jonathan Cornil Scriptie voorgedragen tot het bekomen van de graad van Master in de Taal- en letterkunde (Latijn – Engels) 2011-2012 Promotor: Prof. Dr. W. Verbaal ii Table of Contents Table of Contents iii Foreword v Introduction vii Chapter I. De Excidio Trojae Historia: Philological and Historical Comments 1 A. Dares and His Historia: Shrouded in Mystery 2 1. Who Was ‘Dares the Phrygian’? 2 2. The Role of Cornelius Nepos 6 3. Time of Origin and Literary Environment 9 4. Analysing the Formal Characteristics 11 B. Dares as an Example of ‘Rewriting’ 15 1. Homeric Criticism and the Trojan Legacy in the Middle Ages 15 2. Dares’ Problematic Connection with Dictys Cretensis 20 3. Comments on the ‘Lost Greek Original’ 27 4. Conclusion 31 Chapter II. Translations 33 A. Translating Dares: Frustra Laborat, Qui Omnibus Placere Studet 34 1. Investigating DETH’s Style 34 2. My Own Translations: a Brief Comparison 39 3. A Concise Analysis of R.M. Frazer’s Translation 42 B. Translation I 50 C. Translation II 73 D. Notes 94 Bibliography 95 Appendix: the Latin DETH 99 iii iv Foreword About two years ago, I happened to be researching Cornelius Nepos’ biography of Miltiades as part of an assignment for a class devoted to the study of translating Greek and Latin texts. After heaping together everything I could find about him in the library, I came to the conclusion that I still needed more information. So I decided to embrace my identity as a loyal member of the ‘Internet generation’ and began my virtual journey through the World Wide Web in search of articles on Nepos. -

'The Judgement of Paris' from Robert Graves

Extract, regarding ‘The Judgement of Paris’, from Robert Graves, The Greek Myths: Volume Two. h. Paris's noble birth was soon disclosed by his outstanding beauty, intelligence, and strength: when little more than a child, he routed a band of cattle-thieves and recovered the cows they had stolen, thus winning the surname Alexander.1 Though ranking no higher than a slave at this time, Paris became the chosen lover of Genone, daughter of the river Oeneus, a fountain-nymph. She had been taught the art of prophecy by Rhea, and that of medicine by Apollo while he was acting as Laomedon's herdsman. Paris and Oenone used to herd their flocks and hunt together; he carved her name in the bark of beech-trees and poplars.2 His chief amusement was setting Agelaus's bulls to fight one another; he would crown the victor with flowers, and the loser with straw. When one bull began to win consistently, Paris pitted it against the champions of his neighbours' herds, all of which were defeated. At last he offered to set a golden crown upon the horns of any bull that could overcome his own; so, for a jest, Ares turned himself into a bull, and won the prize. Paris's unhesitating award of this crown to Ares surprised and pleased the gods as they watched from Olympus; which is why Zeus chose him to arbitrate between the three goddesses.3 i. He was herding his cattle on Mount Gargarus, the highest peak of Ida, when Hermes, accompanied by Hera, Athene, and Aphrodite, delivered the golden apple and Zeus's message: 'Paris, since you are as handsome as you are wise in affairs of the heart, Zeus commands you to judge which of these goddesses is the fairest.' Paris accepted the apple doubtfully. -

1 Divine Intervention and Disguise in Homer's Iliad Senior Thesis

Divine Intervention and Disguise in Homer’s Iliad Senior Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Undergraduate School of Arts and Sciences Brandeis University Undergraduate Program in Classical Studies Professor Joel Christensen, Advisor In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts By Joana Jankulla May 2018 Copyright by Joana Jankulla 1 Copyright by Joana Jankulla © 2018 2 Acknowledgements First and foremost, I would like to thank my advisor, Professor Joel Christensen. Thank you, Professor Christensen for guiding me through this process, expressing confidence in me, and being available whenever I had any questions or concerns. I would not have been able to complete this work without you. Secondly, I would like to thank Professor Ann Olga Koloski-Ostrow and Professor Cheryl Walker for reading my thesis and providing me with feedback. The Classics Department at Brandeis University has been an instrumental part of my growth in my four years as an undergraduate, and I am eternally thankful to all the professors and staff members in the department. Thank you to my friends, specifically Erica Theroux, Sarah Jousset, Anna Craven, Rachel Goldstein, Taylor McKinnon and Georgie Contreras for providing me with a lot of emotional support this year. I hope you all know how grateful I am for you as friends and how much I have appreciated your love this year. Thank you to my mom for FaceTiming me every time I was stressed about completing my thesis and encouraging me every step of the way. Finally, thank you to Ian Leeds for dropping everything and coming to me each time I needed it. -

Astrocladistics of the Jovian Trojan Swarms

MNRAS 000,1–26 (2020) Preprint 23 March 2021 Compiled using MNRAS LATEX style file v3.0 Astrocladistics of the Jovian Trojan Swarms Timothy R. Holt,1,2¢ Jonathan Horner,1 David Nesvorný,2 Rachel King,1 Marcel Popescu,3 Brad D. Carter,1 and Christopher C. E. Tylor,1 1Centre for Astrophysics, University of Southern Queensland, Toowoomba, QLD, Australia 2Department of Space Studies, Southwest Research Institute, Boulder, CO. USA. 3Astronomical Institute of the Romanian Academy, Bucharest, Romania. Accepted XXX. Received YYY; in original form ZZZ ABSTRACT The Jovian Trojans are two swarms of small objects that share Jupiter’s orbit, clustered around the leading and trailing Lagrange points, L4 and L5. In this work, we investigate the Jovian Trojan population using the technique of astrocladistics, an adaptation of the ‘tree of life’ approach used in biology. We combine colour data from WISE, SDSS, Gaia DR2 and MOVIS surveys with knowledge of the physical and orbital characteristics of the Trojans, to generate a classification tree composed of clans with distinctive characteristics. We identify 48 clans, indicating groups of objects that possibly share a common origin. Amongst these are several that contain members of the known collisional families, though our work identifies subtleties in that classification that bear future investigation. Our clans are often broken into subclans, and most can be grouped into 10 superclans, reflecting the hierarchical nature of the population. Outcomes from this project include the identification of several high priority objects for additional observations and as well as providing context for the objects to be visited by the forthcoming Lucy mission. -

Nick Susa Epic Mythomemology – the Iliad Book 1: Achilles Was Fighting

Nick Susa Epic Mythomemology – The Iliad Book 1: Achilles was fighting alongside Agamemnon, the King of Argos, during the Trojan war. After winning a battle each was given a war prize, a woman. Achilles was given Briseis, and Agamemnon was given Chryseis. However, the father of Chryseis, Chryses, who was also a priest of Apollo, wasn’t ready to part with his daughter and came with a ransom for his daughter for King Agamemnon. Agamemnon refused the ransom in favor of keeping Chryseis and threatened the priest. Horrified and upset the priest (Chryses) calls upon Apollo and asks him to put a plague upon the Achaean armies, one of which Agamemnon leads. For nine days the armies were struck with a plague, on the tenth Achilles called a meeting to find the reason for the plague. Calchas, a prophet and follower of Apollo, being protected by Achilles, explains that Agamemnon refusing the ransom was the reason for the plague and he must return the girl and make a sacrifice of one hundred cows to Apollo in order to end the plague. Agamemnon decides to appease Apollo, but only if he can take away Achilles war prize, Briseis. Achilles doesn’t believe that Agamemnon should gain Briseis, so the two begin to argue. Achilles decides that he and his men shall not fight in the war because of Agamemnon’s actions. After Agamemnon takes Briseis away, Achilles cries and prays to his mother, Thetis, asking her to have Zeus grant the Achaean armies many loses. Zeus was not around to be asked though, but after twelve days, he returns and promises to Thetis that he will grant the Trojans many victories and the Achaeans many losses. -

Aziz Nikolaos Kilisesi Kazıları 1989-2009

Aziz Nikolaos Kilisesi Kazıları 1989-2009 Yayına Hazırlayanlar Sema Doğan Ebru Fatma Fındık Aziz Nikolaos Kilisesi Kazıları 1989-2009 ISBN 978-9944-483-81-0 Aziz Nikolaos Kilisesi Kazıları 1989-2009 Yayına Hazırlayanlar Sema Doğan Ebru Fatma Fındık Kapak Görseli Aziz Nikolaos Kilisesi, naostan bemaya bakış (Z.M. Yasa / KA-BA) Ofset Hazırlık Homer Kitabevi Baskı Matsis Matbaa Hizmetleri Sanayi ve Ticaret Ltd. Şti. Tevfikbey Mahallesi Dr. Ali Demir Caddesi No: 51 34290 Sefaköy/İstanbul Tel: 0212 624 21 11 Sertifika No: 40421 1. Basım 2018 © Homer Kitabevi ve Yayıncılık Ltd. Şti. Tüm metin ve fotoğrafların yayım hakkı saklıdır. Tanıtım için yapılacak kısa alıntılar dışında yayımcının yazılı izni olmaksızın hiçbir yolla çoğaltılamaz. Homer Kitabevi ve Yayıncılık Ltd. Şti. Tomtom Mah. Yeni Çarşı Caddesi No: 52-1 34433 Beyoğlu/İstanbul Sertifika No: 16972 Tel: (0212) 249 59 02 • (0212) 292 42 79 Faks: (0212) 251 39 62 e-posta: [email protected] www.homerbooks.com Aziz Nikolaos Kilisesi Kazıları 1989-2009 Yayına Hazırlayanlar Sema Doğan Ebru Fatma Fındık Yıldız Ötüken’e… İçindekiler Sunuş 7 Jews and Christians in Ancient Lycia: A Fresh Appraisal Mark Wilson 11 Kaynaklar Eşliğinde Aziz Nikolaos Kilisesi’nin Tarihi Sema Doğan 35 Aziz Nikolaos Kilisesi Kazı Çalışmaları 1989-2009 S Yıldız Ötüken 63 Aziz Nikolaos Kilisesi Projesi 2000-2015 Yılları Arasında Proje Kapsamında Gerçekleştirilen Danışmanlık, Projelendirme, Planlama ve Uygulama Çalışmaları Cengiz Kabaoğlu 139 Malzeme Sorunları ve Koruma Önerileri Bekir Eskici 185 Tuğla Örnekleri Arkeometrik