Title Page Echoes of the Salpinx: the Trumpet in Ancient Greek Culture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Serrated Silver Coinage of Carthage

The serrated silver coinage of Carthage Autor(en): Visonà, Paolo Objekttyp: Article Zeitschrift: Schweizerische numismatische Rundschau = Revue suisse de numismatique = Rivista svizzera di numismatica Band (Jahr): 86 (2007) PDF erstellt am: 11.10.2021 Persistenter Link: http://doi.org/10.5169/seals-178709 Nutzungsbedingungen Die ETH-Bibliothek ist Anbieterin der digitalisierten Zeitschriften. Sie besitzt keine Urheberrechte an den Inhalten der Zeitschriften. Die Rechte liegen in der Regel bei den Herausgebern. Die auf der Plattform e-periodica veröffentlichten Dokumente stehen für nicht-kommerzielle Zwecke in Lehre und Forschung sowie für die private Nutzung frei zur Verfügung. Einzelne Dateien oder Ausdrucke aus diesem Angebot können zusammen mit diesen Nutzungsbedingungen und den korrekten Herkunftsbezeichnungen weitergegeben werden. Das Veröffentlichen von Bildern in Print- und Online-Publikationen ist nur mit vorheriger Genehmigung der Rechteinhaber erlaubt. Die systematische Speicherung von Teilen des elektronischen Angebots auf anderen Servern bedarf ebenfalls des schriftlichen Einverständnisses der Rechteinhaber. Haftungsausschluss Alle Angaben erfolgen ohne Gewähr für Vollständigkeit oder Richtigkeit. Es wird keine Haftung übernommen für Schäden durch die Verwendung von Informationen aus diesem Online-Angebot oder durch das Fehlen von Informationen. Dies gilt auch für Inhalte Dritter, die über dieses Angebot zugänglich sind. Ein Dienst der ETH-Bibliothek ETH Zürich, Rämistrasse 101, 8092 Zürich, Schweiz, www.library.ethz.ch http://www.e-periodica.ch PAOLO VISONÀ THE SERRATED SILVER COINAGE OF CARTHAGE* Plates 5-7 1. INTRODUCTION Serrated silver coinscomprise a distinctive group of Carthaginian issues in precious metal, consisting of reduced shekels and double-shekels, that have not yet been fully studied.1 Even after G.K. Jenkins and R.B. -

VU Research Portal

VU Research Portal The impact of empire on market prices in Babylon Pirngruber, R. 2012 document version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication in VU Research Portal citation for published version (APA) Pirngruber, R. (2012). The impact of empire on market prices in Babylon: in the Late Achaemenid and Seleucid periods, ca. 400 - 140 B.C. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. E-mail address: [email protected] Download date: 25. Sep. 2021 THE IMPACT OF EMPIRE ON MARKET PRICES IN BABYLON in the Late Achaemenid and Seleucid periods, ca. 400 – 140 B.C. R. Pirngruber VRIJE UNIVERSITEIT THE IMPACT OF EMPIRE ON MARKET PRICES IN BABYLON in the Late Achaemenid and Seleucid periods, ca. 400 – 140 B.C. ACADEMISCH PROEFSCHRIFT ter verkrijging van de graad Doctor aan de Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, op gezag van de rector magnificus prof.dr. -

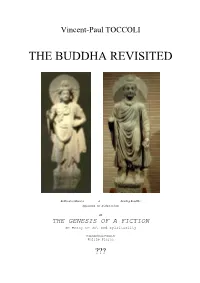

The Buddha Revisited

Vincent-Paul TOCCOLI THE BUDDHA REVISITED Bodhisattva Maitreya & Standing Bouddha Afghanistan, 1er & 2ème sicècles or THE GENESIS OF A FICTION an essay on art and spirituality Translated from French by Philip Pierce ??? "Stories do not belong to eternity "They belong to time "And out of time they grow... "It is in time "That stories, relived and redreamed "Become timeless... "Nations and people are largely the stories they feed themselves "If they tell themselves stories that are lies, "They will suffer the future consequences of those lies. "If they tell themselves stories that free their own truths "They will free their histories forfuture flowerings. (Ben OKRI, Birds of heaven, 25, 15) "Dans leur prétention à la sagesse, "Ils sont devenus fous, "Et ils ont changé la gloire du dieu incorruptible "Contre une représentation, "Simple image d`homme corruptible. (St Paul, to the Romans, 1, 22-23) C O N T E N T S INTRODUCTION FIRST PART: THE MAKING-SENSE TRANSGRESSIONS 1st SECTION: ON THE GANGES SIDE, 5th-1st cent. BC. Chap.1: The Buddhism of the Buddha Chap.2: The state of Buddhism under the last Mauryas 2nd SECTION: ON THE INDUS SIDE, 4th-1st cent. BC. Chap.3: The permanence of Philhellenism, from the Graeco-bactrians to the Scytho-Parthans Chap.4: An approach to the graeco-hellenistic influence SECOND PART: THE ARTIFICIAL FECUNDATIONS 3rd SECTION: THE SYMBOLIC IMAGINARY AND THE REPRESENTATION OF THE SACRED Chap.5: The figurative vision of Buddhism Chap.6: The aesthetic tradition of Greek sculpture 4th SECTION: THE PRECIPITATE IN SPACE -

Archaeology and History of Lydia from the Early Lydian Period to Late Antiquity (8Th Century B.C.-6Th Century A.D.)

Dokuz Eylül University – DEU The Research Center for the Archaeology of Western Anatolia – EKVAM Colloquia Anatolica et Aegaea Congressus internationales Smyrnenses IX Archaeology and history of Lydia from the early Lydian period to late antiquity (8th century B.C.-6th century A.D.). An international symposium May 17-18, 2017 / Izmir, Turkey ABSTRACTS Edited by Ergün Laflı Gülseren Kan Şahin Last Update: 21/04/2017. Izmir, May 2017 Websites: https://independent.academia.edu/TheLydiaSymposium https://www.researchgate.net/profile/The_Lydia_Symposium 1 This symposium has been dedicated to Roberto Gusmani (1935-2009) and Peter Herrmann (1927-2002) due to their pioneering works on the archaeology and history of ancient Lydia. Fig. 1: Map of Lydia and neighbouring areas in western Asia Minor (S. Patacı, 2017). 2 Table of contents Ergün Laflı, An introduction to Lydian studies: Editorial remarks to the abstract booklet of the Lydia Symposium....................................................................................................................................................8-9. Nihal Akıllı, Protohistorical excavations at Hastane Höyük in Akhisar………………………………10. Sedat Akkurnaz, New examples of Archaic architectural terracottas from Lydia………………………..11. Gülseren Alkış Yazıcı, Some remarks on the ancient religions of Lydia……………………………….12. Elif Alten, Revolt of Achaeus against Antiochus III the Great and the siege of Sardis, based on classical textual, epigraphic and numismatic evidence………………………………………………………………....13. Gaetano Arena, Heleis: A chief doctor in Roman Lydia…….……………………………………....14. Ilias N. Arnaoutoglou, Κοινὸν, συμβίωσις: Associations in Hellenistic and Roman Lydia……….……..15. Eirini Artemi, The role of Ephesus in the late antiquity from the period of Diocletian to A.D. 449, the “Robber Synod”.……………………………………………………………………….………...16. Natalia S. Astashova, Anatolian pottery from Panticapaeum…………………………………….17-18. Ayşegül Aykurt, Minoan presence in western Anatolia……………………………………………...19. -

Bullard Eva 2013 MA.Pdf

Marcomannia in the making. by Eva Bullard BA, University of Victoria, 2008 A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of Greek and Roman Studies Eva Bullard 2013 University of Victoria All rights reserved. This thesis may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without the permission of the author. ii Supervisory Committee Marcomannia in the making by Eva Bullard BA, University of Victoria, 2008 Supervisory Committee Dr. John P. Oleson, Department of Greek and Roman Studies Supervisor Dr. Gregory D. Rowe, Department of Greek and Roman Studies Departmental Member iii Abstract Supervisory Committee John P. Oleson, Department of Greek and Roman Studies Supervisor Dr. Gregory D. Rowe, Department of Greek and Roman Studies Departmental Member During the last stages of the Marcommani Wars in the late second century A.D., Roman literary sources recorded that the Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius was planning to annex the Germanic territory of the Marcomannic and Quadic tribes. This work will propose that Marcus Aurelius was going to create a province called Marcomannia. The thesis will be supported by archaeological data originating from excavations in the Roman installation at Mušov, Moravia, Czech Republic. The investigation will examine the history of the non-Roman region beyond the northern Danubian frontier, the character of Roman occupation and creation of other Roman provinces on the Danube, and consult primary sources and modern research on the topic of Roman expansion and empire building during the principate. iv Table of Contents Supervisory Committee ..................................................................................................... -

The Greek World

THE GREEK WORLD THE GREEK WORLD Edited by Anton Powell London and New York First published 1995 by Routledge 11 New Fetter Lane, London EC4P 4EE This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2003. Disclaimer: For copyright reasons, some images in the original version of this book are not available for inclusion in the eBook. Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge 29 West 35th Street, New York, NY 10001 First published in paperback 1997 Selection and editorial matter © 1995 Anton Powell, individual chapters © 1995 the contributors All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Greek World I. Powell, Anton 938 Library of Congress Cataloguing in Publication Data The Greek world/edited by Anton Powell. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. 1. Greece—Civilization—To 146 B.C. 2. Mediterranean Region— Civilization. 3. Greece—Social conditions—To 146 B.C. I. Powell, Anton. DF78.G74 1995 938–dc20 94–41576 ISBN 0-203-04216-6 Master e-book ISBN ISBN 0-203-16276-5 (Adobe eReader Format) ISBN 0-415-06031-1 (hbk) ISBN 0-415-17042-7 (pbk) CONTENTS List of Illustrations vii Notes on Contributors viii List of Abbreviations xii Introduction 1 Anton Powell PART I: THE GREEK MAJORITY 1 Linear -

2210 Bc 2200 Bc 2190 Bc 2180 Bc 2170 Bc 2160 Bc 2150 Bc 2140 Bc 2130 Bc 2120 Bc 2110 Bc 2100 Bc 2090 Bc

2210 BC 2200 BC 2190 BC 2180 BC 2170 BC 2160 BC 2150 BC 2140 BC 2130 BC 2120 BC 2110 BC 2100 BC 2090 BC Fertile Crescent Igigi (2) Ur-Nammu Shulgi 2192-2190BC Dudu (20) Shar-kali-sharri Shu-Turul (14) 3rd Kingdom of 2112-2095BC (17) 2094-2047BC (47) 2189-2169BC 2217-2193BC (24) 2168-2154BC Ur 2112-2004BC Kingdom Of Akkad 2234-2154BC ( ) (2) Nanijum, Imi, Elulu Imta (3) 2117-2115BC 2190-2189BC (1) Ibranum (1) 2180-2177BC Inimabakesh (5) Ibate (3) Kurum (1) 2127-2124BC 2113-2112BC Inkishu (6) Shulme (6) 2153-2148BC Iarlagab (15) 2121-2120BC Puzur-Sin (7) Iarlaganda ( )(7) Kingdom Of Gutium 2177-2171BC 2165-2159BC 2142-2127BC 2110-2103BC 2103-2096BC (7) 2096-2089BC 2180-2089BC Nikillagah (6) Elulumesh (5) Igeshaush (6) 2171-2165BC 2159-2153BC 2148-2142BC Iarlagash (3) Irarum (2) Hablum (2) 2124-2121BC 2115-2113BC 2112-2110BC ( ) (3) Cainan 2610-2150BC (460 years) 2120-2117BC Shelah 2480-2047BC (403 years) Eber 2450-2020BC (430 years) Peleg 2416-2177BC (209 years) Reu 2386-2147BC (207 years) Serug 2354-2124BC (200 years) Nahor 2324-2176BC (199 years) Terah 2295-2090BC (205 years) Abraham 2165-1990BC (175) Genesis (Moses) 1)Neferkare, 2)Neferkare Neby, Neferkamin Anu (2) 3)Djedkare Shemay, 4)Neferkare 2169-2167BC 1)Meryhathor, 2)Neferkare, 3)Wahkare Achthoes III, 4)Marykare, 5)............. (All Dates Unknown) Khendu, 5)Meryenhor, 6)Neferkamin, Kakare Ibi (4) 7)Nykare, 8)Neferkare Tereru, 2167-2163 9)Neferkahor Neferkare (2) 10TH Dynasty (90) 2130-2040BC Merenre Antyemsaf II (All Dates Unknown) 2163-2161BC 1)Meryibre Achthoes I, 2)............., 3)Neferkare, 2184-2183BC (1) 4)Meryibre Achthoes II, 5)Setut, 6)............., Menkare Nitocris Neferkauhor (1) Wadjkare Pepysonbe 7)Mery-........, 8)Shed-........, 9)............., 2183-2181BC (2) 2161-2160BC Inyotef II (-1) 2173-2169BC (4) 10)............., 11)............., 12)User...... -

Hugh Lindsay, Strabo and the Shape of His Historika Hypomnemata

The Ancient History Bulletin VOLUME TWENTY-EIGHT: 2014 NUMBERS 1-2 Edited by: Edward Anson David Hollander Timothy Howe Joseph Roisman John Vanderspoel Pat Wheatley Sabine Müller ISSN 0835-3638 ANCIENT HISTORY BULLETIN Volume 28 (2014) Numbers 1-2 Edited by: Edward Anson, David Hollander, Sabine Müller, Joseph Roisman, John Vanderspoel, Pat Wheatley Senior Editor: Timothy Howe Editorial correspondents Elizabeth Baynham, Hugh Bowden, Franca Landucci Gattinoni, Alexander Meeus, Kurt Raaflaub, P.J. Rhodes, Robert Rollinger, Carol Thomas, Victor Alonso Troncoso Contents of volume twenty-eight Numbers 1-2 1 Hugh Lindsay, Strabo and the shape of his Historika Hypomnemata 20 Paul McKechnie, W.W. Tarn and the philosophers 37 Monica D’Agostini, The Shade of Andromache: Laodike of Sardis between Homer and Polybios 61 John Shannahan, Two Notes on the Battle of Cunaxa NOTES TO CONTRIBUTORS AND SUBSCRIBERS The Ancient History Bulletin was founded in 1987 by Waldemar Heckel, Brian Lavelle, and John Vanderspoel. The board of editorial correspondents consists of Elizabeth Baynham (University of Newcastle), Hugh Bowden (Kings College, London), Franca Landucci Gattinoni (Università Cattolica, Milan), Alexander Meeus (University of Leuven), Kurt Raaflaub (Brown University), P.J. Rhodes (Durham University), Robert Rollinger (Universität Innsbruck), Carol Thomas (University of Washington), Victor Alonso Troncoso (Universidade da Coruña) AHB is currently edited by: Timothy Howe (Senior Editor: [email protected]), Edward Anson, David Hollander, Sabine Müller, Joseph Roisman, John Vanderspoel and Pat Wheatley. AHB promotes scholarly discussion in Ancient History and ancillary fields (such as epigraphy, papyrology, and numismatics) by publishing articles and notes on any aspect of the ancient world from the Near East to Late Antiquity. -

Politics and Policy: Rome and Liguria, 200-172 B.C

Politics and policy: Rome and Liguria, 200-172 B.C. Eric Brousseau, Department of History McGill University, Montreal June, 2010 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Arts. ©Eric Brousseau 2010 i Abstract Stephen Dyson’s The Creation of the Roman Frontier employs various anthropological models to explain the development of Rome’s republican frontiers. His treatment of the Ligurian frontier in the second century BC posits a Ligurian ‘policy’ crafted largely by the Senate and Roman ‘frontier tacticians’ (i.e. consuls). Dyson consciously avoids incorporating the pressures of domestic politics and the dynamics of aristocratic competition. But his insistence that these factors obscure policy continuities is incorrect. Politics determined policy. This thesis deals with the Ligurian frontier from 200 to 172 BC, years in which Roman involvement in the region was most intense. It shows that individual magistrates controlled policy to a much greater extent than Dyson and other scholars have allowed. The interplay between the competing forces of aristocratic competition and Senatorial consensus best explains the continuities and shifts in regional policy. Abstrait The Creation of the Roman Frontier, l’œuvre de Stephen Dyson, utilise plusieurs modèles anthropologiques pour illuminer le développement de la frontière républicaine. Son traitement de la frontière Ligurienne durant la deuxième siècle avant J.-C. postule une ‘politique’ envers les Liguriennes déterminer par le Sénat et les ‘tacticiens de la frontière romain’ (les consuls). Dyson fais exprès de ne pas tenir compte des forces de la politique domestique et la compétition aristocratique. Mais son insistance que ces forces cachent les continuités de la politique Ligurienne est incorrecte. -

THE MARS ULTOR COINS of C. 19-16 BC

UNIWERSYTET ZIELONOGÓRSKI IN GREMIUM 9/2015 Studia nad Historią, Kulturą i Polityką s . 7-30 Victoria Győri King’s College, London THE MARS ULTOR COINS OF C. 19-16 BC In 42 BC Augustus vowed to build a temple of Mars if he were victorious in aveng- ing the assassination of his adoptive father Julius Caesar1 . While ultio on Brutus and Cassius was a well-grounded theme in Roman society at large and was the principal slogan of Augustus and the Caesarians before and after the Battle of Philippi, the vow remained unfulfilled until 20 BC2 . In 20 BC, Augustus renewed his vow to Mars Ultor when Roman standards lost to the Parthians in 53, 40, and 36 BC were recovered by diplomatic negotiations . The temple of Mars Ultor then took on a new role; it hon- oured Rome’s ultio exacted from the Parthians . Parthia had been depicted as a prime foe ever since Crassus’ defeat at Carrhae in 53 BC . Before his death in 44 BC, Caesar planned a Parthian campaign3 . In 40 BC L . Decidius Saxa was defeated when Parthian forces invaded Roman Syria . In 36 BC Antony’s Parthian campaign was in the end unsuccessful4 . Indeed, the Forum Temple of Mars Ultor was not dedicated until 2 BC when Augustus received the title of Pater Patriae and when Gaius departed to the East to turn the diplomatic settlement of 20 BC into a military victory . Nevertheless, Augustus made his Parthian success of 20 BC the centre of a grand “propagandistic” programme, the principal theme of his new forum, and the reason for renewing his vow to build a temple to Mars Ultor . -

CALENDARS by David Le Conte

CALENDARS by David Le Conte This article was published in two parts, in Sagittarius (the newsletter of La Société Guernesiaise Astronomy Section), in July/August and September/October 1997. It was based on a talk given by the author to the Astronomy Section on 20 May 1997. It has been slightly updated to the date of this transcript, December 2007. Part 1 What date is it? That depends on the calendar used:- Gregorian calendar: 1997 May 20 Julian calendar: 1997 May 7 Jewish calendar: 5757 Iyyar 13 Islamic Calendar: 1418 Muharaim 13 Persian Calendar: 1376 Ordibehesht 30 Chinese Calendar: Shengxiao (Ox) Xin-You 14 French Rev Calendar: 205, Décade I Mayan Calendar: Long count 12.19.4.3.4 tzolkin = 2 Kan; haab = 2 Zip Ethiopic Calendar: 1990 Genbot 13 Coptic Calendar: 1713 Bashans 12 Julian Day: 2450589 Modified Julian Date: 50589 Day number: 140 Julian Day at 8.00 pm BST: 2450589.292 First, let us note the difference between calendars and time-keeping. The calendar deals with intervals of at least one day, while time-keeping deals with intervals less than a day. Calendars are based on astronomical movements, but they are primarily for social rather than scientific purposes. They are intended to satisfy the needs of society, for example in matters such as: agriculture, hunting. migration, religious and civil events. However, it has also been said that they do provide a link between man and the cosmos. There are about 40 calendars now in use. and there are many historical ones. In this article we will consider six principal calendars still in use, relating them to their historical background and astronomical foundation. -

Calendar of Roman Events

Introduction Steve Worboys and I began this calendar in 1980 or 1981 when we discovered that the exact dates of many events survive from Roman antiquity, the most famous being the ides of March murder of Caesar. Flipping through a few books on Roman history revealed a handful of dates, and we believed that to fill every day of the year would certainly be impossible. From 1981 until 1989 I kept the calendar, adding dates as I ran across them. In 1989 I typed the list into the computer and we began again to plunder books and journals for dates, this time recording sources. Since then I have worked and reworked the Calendar, revising old entries and adding many, many more. The Roman Calendar The calendar was reformed twice, once by Caesar in 46 BC and later by Augustus in 8 BC. Each of these reforms is described in A. K. Michels’ book The Calendar of the Roman Republic. In an ordinary pre-Julian year, the number of days in each month was as follows: 29 January 31 May 29 September 28 February 29 June 31 October 31 March 31 Quintilis (July) 29 November 29 April 29 Sextilis (August) 29 December. The Romans did not number the days of the months consecutively. They reckoned backwards from three fixed points: The kalends, the nones, and the ides. The kalends is the first day of the month. For months with 31 days the nones fall on the 7th and the ides the 15th. For other months the nones fall on the 5th and the ides on the 13th.