Becoming Macedonian: Name Mapping and Ethnic Identity. the Case of Hephaistion*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CHERSONESUS MUSEUM M.I. ZOLOTAREV (Sevastopol) Abstract

CHERSONESUS MUSEUM M.I. ZOLOTAREV (Sevastopol) Abstract The first excavations of the ancient Greek and Byzatine city of Chersonesus in the Crimea occurred episodically after the 1820s, but in 1888 a full research program was initiated under the aegis of the Imperial Archaeological Commission. By the time after the Second World War much of the ancient city had been excavated, and investigation began of the Chersonesian chora and the Archaic settlement underlying the Doric city. In 1892 a small site museum was established which in 1924 took over apartments in the Monastery of Chersonesus and establish- ed the first exhibition of excavation finds. The Museum collections, some of which have now been published, contain over 120,000 items, including a unique collection of over 400 local grave monuments. The State Historico-Archaeological Preserve of Chersonesus in modern Sevastopol in the Crimea embraces the territory of the ancient Greek and Byzantine city of Chersonesus. The history of its archaeological investigation covers about one and a half centuries, the first excavations dating back to the first decades of the 19th century. Those were undertaken by several intellec- tuals from among the officers of the Black Sea navy. In 1827 by order of Admiral S. Greig, the commander of the Black Sea squadron, Lieutenant von Kruse excavated several Byzantine monuments in Chersonesus. That was done to commemorate the conversion of Russia to Christianity in 988. From then until 1888 all archaeological works carried out in Chersonesus were merely episodic. We should mention, however, the excavations of 1854 under- taken by Count A.S. -

Seven Churches of Revelation Turkey

TRAVEL GUIDE SEVEN CHURCHES OF REVELATION TURKEY TURKEY Pergamum Lesbos Thyatira Sardis Izmir Chios Smyrna Philadelphia Samos Ephesus Laodicea Aegean Sea Patmos ASIA Kos 1 Rhodes ARCHEOLOGICAL MAP OF WESTERN TURKEY BULGARIA Sinanköy Manya Mt. NORTH EDİRNE KIRKLARELİ Selimiye Fatih Iron Foundry Mosque UNESCO B L A C K S E A MACEDONIA Yeni Saray Kırklareli Höyük İSTANBUL Herakleia Skotoussa (Byzantium) Krenides Linos (Constantinople) Sirra Philippi Beikos Palatianon Berge Karaevlialtı Menekşe Çatağı Prusias Tauriana Filippoi THRACE Bathonea Küçükyalı Ad hypium Morylos Dikaia Heraion teikhos Achaeology Edessa Neapolis park KOCAELİ Tragilos Antisara Abdera Perinthos Basilica UNESCO Maroneia TEKİRDAĞ (İZMİT) DÜZCE Europos Kavala Doriskos Nicomedia Pella Amphipolis Stryme Işıklar Mt. ALBANIA Allante Lete Bormiskos Thessalonica Argilos THE SEA OF MARMARA SAKARYA MACEDONIANaoussa Apollonia Thassos Ainos (ADAPAZARI) UNESCO Thermes Aegae YALOVA Ceramic Furnaces Selectum Chalastra Strepsa Berea Iznik Lake Nicea Methone Cyzicus Vergina Petralona Samothrace Parion Roman theater Acanthos Zeytinli Ada Apamela Aisa Ouranopolis Hisardere Dasaki Elimia Pydna Barçın Höyük BTHYNIA Galepsos Yenibademli Höyük BURSA UNESCO Antigonia Thyssus Apollonia (Prusa) ÇANAKKALE Manyas Zeytinlik Höyük Arisbe Lake Ulubat Phylace Dion Akrothooi Lake Sane Parthenopolis GÖKCEADA Aktopraklık O.Gazi Külliyesi BİLECİK Asprokampos Kremaste Daskyleion UNESCO Höyük Pythion Neopolis Astyra Sundiken Mts. Herakleum Paşalar Sarhöyük Mount Athos Achmilleion Troy Pessinus Potamia Mt.Olympos -

Mindaugas STROCKIS a NEW INTERPRETATION of THE

BALTISTICA VII PRIEDAS 2011 243–253 Mindaugas STROCKIS Vilnius University A NEW INTERPRETATION OF THE SYLLABLE TONES IN DORIC GREEK A thorough understanding of ancient Greek accentuation, especially of the nature of the Greek syllable tones, can contribute to our knowledge of the accentuation of other Indo-European languages, among them the Baltic languages, at least by furnishing some useful typological examples. We possess a fairly good knowledge of ancient Greek accentuation, but most of it is confined to the classical form of Greek, that is, Attic. The accentuation of the Doric dialect is scantily attested, and its relationship to the Attic is not quite clear. The amount of evidence that we have about Doric accentuation is just such as to make the problem interesting: not enough for obvious and decisive conclusions, but neither so little that one must abandon any attempt at interpretation altogether. The evidence about the accentuation of literary Doric that was gathered by classical scholarship from the papyri of Alcman, Pindar, and Theocritus, as well as from the descriptions of ancient grammarians, was summarised by Ahrens in 1843, and little, if any, new information was added since that time. Ahrens’ data can be summarised as follows: Acute in the last syllable where Attic has non-final accentuation: Doric φρᾱτήρ : Attic φρᾱ́τηρ. Acute in the names in -ᾱν (< -ᾱων), instead of Attic circumflex: Doric Ποτιδᾱ́ν : Attic Ποσειδῶν (< -δᾱ́ων); Ἀλκμᾱ́ν. Acute in monosyllabic nouns, where Attic has circumflex: Doric σκώρ : Attic σκῶρ, Doric γλαύξ : Attic γλαῦξ. No ‘short diphthongs’; all final -αι and -οι are ‘long’: nom. pl. -

First Wave COVID-19 Pandemics in Greece Anastasiou E., Duquenne M-N

First wave COVID-19 pandemics in Greece Anastasiou E., Duquenne M-N. The role of demographic, social and geographical factors In life satisfaction during the lockdown Preprint: DOI: 10.13140/RG.2.2.23684.55689 First wave COVID-19 pandemics in Greece: The role of demographic, social and geographical factors in life satisfaction during the lockdown Evgenia Anastasiou, Marie-Noelle Duquenne Laboratory of Demographic and Social Analyses (LDSA) Department of Planning and Regional Development, University of Thessaly, Volos, Greece, [email protected], [email protected] Abstract The onset of the coronavirus pandemic led to profound changes in populations' everyday lives. The main purpose of this research is to investigate the factors that affected life satisfaction during the first lockdown wave in Greece. A web-based survey was developed, and 4,305 questionnaires were completed corresponding to all Greek regional units. Statistical modeling (Multivariate Logistic Regression) was performed to evaluate in which extent significant geographical attributes and socioeconomic characteristics are likely to influence life satisfaction during the lockdown due to the pandemic. In the course of the present work, key findings emerge: Social distancing and confinement measures affected mostly men in relation to women. There is a strong positive association between life satisfaction and age, especially as regards older population. The change in the employment status, the increase in psychosomatic disorders and the increased usage of social media are also likely to impact negatively people’s life satisfaction. On the contrary, trust in government and the media and limited health concerns seem to have a strong association with subjective well-being. -

Hadrian and the Greek East

HADRIAN AND THE GREEK EAST: IMPERIAL POLICY AND COMMUNICATION DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By Demetrios Kritsotakis, B.A, M.A. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2008 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Fritz Graf, Adviser Professor Tom Hawkins ____________________________ Professor Anthony Kaldellis Adviser Greek and Latin Graduate Program Copyright by Demetrios Kritsotakis 2008 ABSTRACT The Roman Emperor Hadrian pursued a policy of unification of the vast Empire. After his accession, he abandoned the expansionist policy of his predecessor Trajan and focused on securing the frontiers of the empire and on maintaining its stability. Of the utmost importance was the further integration and participation in his program of the peoples of the Greek East, especially of the Greek mainland and Asia Minor. Hadrian now invited them to become active members of the empire. By his lengthy travels and benefactions to the people of the region and by the creation of the Panhellenion, Hadrian attempted to create a second center of the Empire. Rome, in the West, was the first center; now a second one, in the East, would draw together the Greek people on both sides of the Aegean Sea. Thus he could accelerate the unification of the empire by focusing on its two most important elements, Romans and Greeks. Hadrian channeled his intentions in a number of ways, including the use of specific iconographical types on the coinage of his reign and religious language and themes in his interactions with the Greeks. In both cases it becomes evident that the Greeks not only understood his messages, but they also reacted in a positive way. -

Alexander the Great, in Case That, Having Completed the Conquest of Asia, He Should Have Turned His Arms on Europe

Alexander the Great, in case that, having completed the conquest of Asia, he should have turned his arms on Europe. 17 Nothing can be found farther from my intention, since the commencement of this history, than to digress, more than necessity required, from the course of narration; and, by embellishing my work with variety, to seek pleasing resting-places, as it were, for my readers, and relaxation for my own mind: nevertheless, the mention of so great a king and commander, now calls forth to public view those silent reflections, whom Alexander must have fought. Manlius Torquatus, had he met him in the field, might, perhaps, have yielded to Alexander in discharging military duties in battle (for these also render him no less illustrious); and so might Valerius Corvus; men who were distinguished soldiers, before they became commanders. The same, too, might have been the case with the Decii, who, after devoting their persons, rushed upon the enemy; or of Papirius Cursor, though possessed of such powers, both of body and mind. By the counsels of one youth, it is possible the wisdom of a whole senate, not to mention individuals, might have been baffled, [consisting of such members,] that he alone, who declared that "it consisted of kings," conceived a correct idea of a Roman senate. But then the danger was, that with more judgment than any one of those whom I have named he might choose ground for an encampment, provide supplies, guard against stratagems, distinguish the season for fighting, form his line of battle, or strengthen it properly with reserves. -

The Fleet of Syracuse (480-413 BCE)

ANDREAS MORAKIS The Fleet of Syracuse (480-413 BCE) The Deinomenids The ancient sources make no reference to the fleet of Syracuse until the be- ginning of the 5th century BCE. In particular, Thucydides, when considering the Greek maritime powers at the time of the rise of the Athenian empire, includes among them the tyrants of Sicily1. Other sources refer more precisely to Gelon’s fleet, during the Carthaginian invasion in Sicily. Herodotus, when the Greeks en- voys asked for Gelon’s help to face Xerxes’ attack, mentions the lord of Syracuse promising to provide, amongst other things, 200 triremes in return of the com- mand of the Greek forces2. The same number of ships is also mentioned by Ti- maeus3 and Ephorus4. It is very odd, though, that we hear nothing of this fleet during the Carthaginian campaign and the Battle of Himera in either the narration of Diodorus, or the briefer one of Herodotus5. Nevertheless, other sources imply some kind of naval fighting in Himera. Pausanias saw offerings from Gelon and the Syracusans taken from the Phoenicians in either a sea or a land battle6. In addition, the Scholiast to the first Pythian of Pindar, in two different situations – the second one being from Ephorus – says that Gelon destroyed the Carthaginians in a sea battle when they attacked Sicily7. 1 Thuc. I 14, 2: ὀλίγον τε πρὸ τῶν Μηδικῶν καὶ τοῦ ∆αρείου θανάτου … τριήρεις περί τε Σικελίαν τοῖς τυράννοις ἐς πλῆθος ἐγένοντο καὶ Κερκυραίοις. 2 Hdt. VII 158. 3 Timae. FGrHist 566 F94= Polyb. XII 26b, 1-5, but the set is not the court of Gelon, but the conference of the mainland Greeks in Corinth. -

Abstracts-Booklet-Lamp-Symposium-1

Dokuz Eylül University – DEU The Research Center for the Archaeology of Western Anatolia – EKVAM Colloquia Anatolica et Aegaea Congressus internationales Smyrnenses XI Ancient terracotta lamps from Anatolia and the eastern Mediterranean to Dacia, the Black Sea and beyond. Comparative lychnological studies in the eastern parts of the Roman Empire and peripheral areas. An international symposium May 16-17, 2019 / Izmir, Turkey ABSTRACTS Edited by Ergün Laflı Gülseren Kan Şahin Laurent Chrzanovski Last update: 20/05/2019. Izmir, 2019 Websites: https://independent.academia.edu/TheLydiaSymposium https://www.researchgate.net/profile/The_Lydia_Symposium Logo illustration: An early Byzantine terracotta lamp from Alata in Cilicia; museum of Mersin (B. Gürler, 2004). 1 This symposium is dedicated to Professor Hugo Thoen (Ghent / Deinze) who contributed to Anatolian archaeology with his excavations in Pessinus. 2 Table of contents Ergün Laflı, An introduction to the ancient lychnological studies in Anatolia, the eastern Mediterranean, Dacia, the Black Sea and beyond: Editorial remarks to the abstract booklet of the symposium...................................6-12. Program of the international symposium on ancient lamps in Anatolia, the eastern Mediterranean, Dacia, the Black Sea and beyond..........................................................................................................................................12-15. Abstracts……………………………………...................................................................................16-67. Constantin -

Ancient History Sourcebook: 11Th Brittanica: Sparta SPARTA an Ancient City in Greece, the Capital of Laconia and the Most Powerful State of the Peloponnese

Ancient History Sourcebook: 11th Brittanica: Sparta SPARTA AN ancient city in Greece, the capital of Laconia and the most powerful state of the Peloponnese. The city lay at the northern end of the central Laconian plain, on the right bank of the river Eurotas, a little south of the point where it is joined by its largest tributary, the Oenus (mount Kelefina). The site is admirably fitted by nature to guard the only routes by which an army can penetrate Laconia from the land side, the Oenus and Eurotas valleys leading from Arcadia, its northern neighbour, and the Langada Pass over Mt Taygetus connecting Laconia and Messenia. At the same time its distance from the sea-Sparta is 27 m. from its seaport, Gythium, made it invulnerable to a maritime attack. I.-HISTORY Prehistoric Period.-Tradition relates that Sparta was founded by Lacedaemon, son of Zeus and Taygete, who called the city after the name of his wife, the daughter of Eurotas. But Amyclae and Therapne (Therapnae) seem to have been in early times of greater importance than Sparta, the former a Minyan foundation a few miles to the south of Sparta, the latter probably the Achaean capital of Laconia and the seat of Menelaus, Agamemnon's younger brother. Eighty years after the Trojan War, according to the traditional chronology, the Dorian migration took place. A band of Dorians united with a body of Aetolians to cross the Corinthian Gulf and invade the Peloponnese from the northwest. The Aetolians settled in Elis, the Dorians pushed up to the headwaters of the Alpheus, where they divided into two forces, one of which under Cresphontes invaded and later subdued Messenia, while the other, led by Aristodemus or, according to another version, by his twin sons Eurysthenes and Procles, made its way down the Eurotas were new settlements were formed and gained Sparta, which became the Dorian capital of Laconia. -

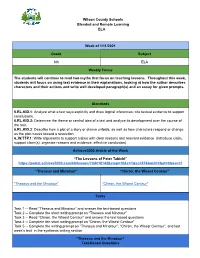

Ms. Legrange's Lesson Plans

Wilson County Schools Blended and Remote Learning ELA Week of 1/11/2021 Grade Subject 6th ELA Weekly Focus The students will continue to read two myths that focus on teaching lessons. Throughout this week, students will focus on using text evidence in their explanations, looking at how the author describes characters and their actions and write well developed paragraph(s) and an essay for given prompts. Standards 6.RL.KID.1: Analyze what a text says explicitly and draw logical inferences; cite textual evidence to support conclusions. 6.RL.KID.2: Determine the theme or central idea of a text and analyze its development over the course of the text. 6.RL.KID.3: Describe how a plot of a story or drama unfolds, as well as how characters respond or change as the plot moves toward a resolution. 6..W.TTP.1 : Write arguments to support claims with clear reasons and relevant evidence (introduce claim, support claim(s), organize reasons and evidence, effective conclusion). Achieve3000 Article of the Week “The Lessons of Peter Tabichi” https://portal.achieve3000.com/kb/lesson/?lid=18142&step=10&c=1&sc=276&oid=0&ot=0&asn=1 “Theseus and Minotaur” “Chiron, the Wisest Centaur” "Theseus and the Minotaur" "Chiron, the Wisest Centaur" Tasks Task 1 -- Read “Theseus and Minotaur” and answer the text-based questions Task 2 -- Complete the short writing prompt on “Theseus and Minotaur” Task 3 -- Read ”Chiron, the Wisest Centaur” and answer the text-based questions Task 4 -- Complete the short writing prompt on “Chiron, the Wisest Centaur” Task 5 -- Complete the writing prompt on “Theseus and Minotaur”, “Chiron, the Wisest Centaur”, and last week’s text in the synthesis writing section. -

The Silent Race Author(S): Standish O'grady Source: the Irish Review (Dublin), Vol

Irish Review (Dublin) The Silent Race Author(s): Standish O'Grady Source: The Irish Review (Dublin), Vol. 1, No. 7 (Sep., 1911), pp. 313-321 Published by: Irish Review (Dublin) Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/30062738 . Accessed: 14/06/2014 05:40 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Irish Review (Dublin) is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Irish Review (Dublin). http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 185.44.77.128 on Sat, 14 Jun 2014 05:40:03 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions THE IRISH REVIEW 4 C~MIONTHLY MIAGAZINE OF IRISH LITERATURE, e4RT & SCIENCE SEPTEMBER 911 The Silent Race By STANDISH O' uRADY WHEN Byron was brooding over the possibility of an insurgent and re-surgent Greece, he thought especially of the Dorians, whether any true Dorian blood still ran there to answer the call of the captains, and thought there did. " On Suli's steep and Parga's shore Exists the remnant of a line Such as the Doric mothers bore: And here perhaps some seed is sown The Heracleidan blood might own." "Heracleidan," for the Doric-Spartan Chiefs claimed descent from Heracles. -

Herodotus' Four Markers of Greek Identity (Ch

Loyola Marymount University From the SelectedWorks of Katerina Zacharia September, 2008 Hellenisms (ii), Herodotus' Four Markers of Greek Identity (ch. 1) Katerina Zacharia, Loyola Marymount University Available at: https://works.bepress.com/katerina_zacharia/15/ 1. Herodotus’ Four Markers of Greek Identity Katerina Zacharia [...] πρὸς δὲ τοὺς ἀπὸ Σπάρτης ἀγγέλους τάδε· Τὸ μὲν δεῖσαι Λακεδαιμονίους μὴ ὁμολογήσωμεν τῷ βαρβάρῳ κάρτα ἀνθρωπήιον ἦν. ἀτὰρ αἰσχρῶς γε οἴκατε ἐξεπιστάμενοι τὸ Ἀθηναίων φρόνημα ἀρρωδῆσαι, ὅτι οὔτε χρυσός ἐστι γῆς οὐδαμόθι τοσοῦτος οὔτε χώρη καλλει καὶ ἀρετῇ μέγα ὑπερφέρουσα, τὰ ἡμεῖς δεξάμενοι ἐθέλοιμεν ἂν μηδίσαντες καταδουλῶσαι τὴν Ἑλλάδα. Πολλὰ τε γὰρ καὶ μεγαλα ἐστι τὰ διακωλύοντα ταῦτα μὴ ποιέειν μηδ᾿ ἢν ἐθέλωμεν, πρῶτα μὲν καὶ μέγιστα τῶν θεῶν τὰ ἀγάλματα καὶ τὰ οἰκήματα ἐμπεπρησμένα τε καὶ συγκεχωσμένα, τοῖσι ἡμέας ἀναγκαίως ἔχει τιμωρέειν ἐς τὰ μέγιστα μᾶλλον ἤ περ ὁμολογέειν τῷ ταῦτα ἐργασαμένῳ, αὖτις δὲ τὸ Ἑλληνικὸν, ἐὸν ὅμαιμόν τε καὶ ὁμόγλωσσον, καὶ θεῶν ἱδρύματά τε κοινὰ καὶ θυσίαι ἤθεά τε ὁμότροπα, τῶν προδότας γενέσθαι Ἀθηναίους οὐκ ἂν εὖ ἔχοι. ἐπίστασθέ τε οὕτω, εἰ μὴ καὶ πρότερον ἐτύγχανετε ἐπιστάμενοι, ἔστ᾿ ἂν καὶ εἶς περιῇ Ἀθηναίων, μηδαμὰ ὁμολογήσοντας ἡμέας Ξέρξῃ .1 Herodotus, Histories, 8, 144.1–3 1. The Sources: Some Qualifiers All contributors were invited to think about the four characteristic features of Hellenism (blood, language, religion, and customs) listed by some anonymous Athenian speakers at the end of Herodotus VIII, in the caption of this chapter. Some of the questions the contributors were asked to explore are: How far has it been true historically that these four features have acted 1 “To the Spartan envoys they said: ‘No doubt it was natural that the Lacedaemonians should dread the possibility of our making terms with Persia; none the less it shows a poor estimate of the spirit of Athens.