THE LOEB CLASSICAL LIBRARY Rounded by J'ames LOEB, LL.D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CLAS 4000 Seminar in Classics on Seneca's Thyestes and LATN 4002 Roman Drama

CLAS 4000 Seminar in Classics on Seneca’s Thyestes and LATN 4002 Roman Drama http://myweb.ecu.edu/stevensj/CLAS4000/2016syllabus.pdf Prof. John A. Stevens Spring 2016 Office: Ragsdale 133 [email protected] Office Hours: TTh 11-1:30 and by appt. (252) 328-6056 Objectives. Upon completion of this course, you will be able to: • Situate Senecan tragedy in the contexts of Roman literature, history and political philosophy • Analyze the elements of Roman Stoicism present in Seneca’s Thyestes • Characterize contemporary literary approaches to the play • Evaluate the play’s literary and philosophical elements as an integral whole Writing Intensive (WI) CLAS 4000 is a writing intensive course in the Writing Across the Curriculum Program at East Carolina University. With committee approval, this course contributes to the twelve-hour WI requirement for students at ECU. Additional information is available at: http://www.ecu.edu/writing/wac/. WI Course goals: • Use writing to investigate complex, relevant topics and address significant questions through engagement with and effective use of credible sources; • Produce writing that reflects an awareness of context, purpose, and audience, particularly within the written genres (including genres that integrate writing with visuals, audio or other multi-modal components) of their major disciplines and/or career fields; • Understand that writing as a process made more effective through drafts and revision; • Produce writing that is proofread and edited to avoid grammatical and mechanical errors; • Ability to assess and explain the major choices made in the writing process. • Students are responsible for uploading the following to iWebfolio (via Courses/Student Portfolio in OneStop): 1) A final draft of a major writing project from the WI course, 2) A description of the assignment for which the project was written, and 3) A writing self-analysis document (a component of our QEP). -

Iphigenia in Aulis by Euripides Translated by Nicholas Rudall Directed by Charles Newell

STUDY GUIDE Photo of Mark L. Montgomery, Stephanie Andrea Barron, and Sandra Marquez by joe mazza/brave lux, inc Sponsored by Iphigenia in Aulis by Euripides Translated by Nicholas Rudall Directed by Charles Newell SETTING The action takes place in east-central Greece at the port of Aulis, on the Euripus Strait. The time is approximately 1200 BCE. CHARACTERS Agamemnon father of Iphigenia, husband of Clytemnestra and King of Mycenae Menelaus brother of Agamemnon Clytemnestra mother of Iphigenia, wife of Agamemnon Iphigenia daughter of Agamemnon and Clytemnestra Achilles son of Peleus Chorus women of Chalcis who came to Aulis to see the Greek army Old Man servant of Agamemnon, was given as part of Clytemnestra’s dowry Messenger ABOUT THE PLAY Iphigenia in Aulis is the last existing work of the playwright Euripides. Written between 408 and 406 BCE, the year of Euripides’ death, the play was first produced the following year in a trilogy with The Bacchaeand Alcmaeon in Corinth by his son, Euripides the Younger, and won the first place at the Athenian City Dionysia festival. Agamemnon Costume rendering by Jacqueline Firkins. 2 SYNOPSIS At the start of the play, Agamemnon reveals to the Old Man that his army and warships are stranded in Aulis due to a lack of sailing winds. The winds have died because Agamemnon is being punished by the goddess Artemis, whom he offended. The only way to remedy this situation is for Agamemnon to sacrifice his daughter, Iphigenia, to the goddess Artemis. Agamemnon then admits that he has sent for Iphigenia to be brought to Aulis but he has changed his mind. -

Ms. Legrange's Lesson Plans

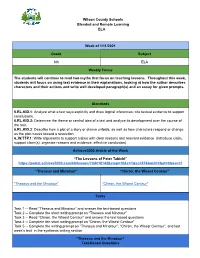

Wilson County Schools Blended and Remote Learning ELA Week of 1/11/2021 Grade Subject 6th ELA Weekly Focus The students will continue to read two myths that focus on teaching lessons. Throughout this week, students will focus on using text evidence in their explanations, looking at how the author describes characters and their actions and write well developed paragraph(s) and an essay for given prompts. Standards 6.RL.KID.1: Analyze what a text says explicitly and draw logical inferences; cite textual evidence to support conclusions. 6.RL.KID.2: Determine the theme or central idea of a text and analyze its development over the course of the text. 6.RL.KID.3: Describe how a plot of a story or drama unfolds, as well as how characters respond or change as the plot moves toward a resolution. 6..W.TTP.1 : Write arguments to support claims with clear reasons and relevant evidence (introduce claim, support claim(s), organize reasons and evidence, effective conclusion). Achieve3000 Article of the Week “The Lessons of Peter Tabichi” https://portal.achieve3000.com/kb/lesson/?lid=18142&step=10&c=1&sc=276&oid=0&ot=0&asn=1 “Theseus and Minotaur” “Chiron, the Wisest Centaur” "Theseus and the Minotaur" "Chiron, the Wisest Centaur" Tasks Task 1 -- Read “Theseus and Minotaur” and answer the text-based questions Task 2 -- Complete the short writing prompt on “Theseus and Minotaur” Task 3 -- Read ”Chiron, the Wisest Centaur” and answer the text-based questions Task 4 -- Complete the short writing prompt on “Chiron, the Wisest Centaur” Task 5 -- Complete the writing prompt on “Theseus and Minotaur”, “Chiron, the Wisest Centaur”, and last week’s text in the synthesis writing section. -

Loeb Lucian Vol5.Pdf

THE LOEB CLASSICAL LIBRARY FOUNDED BY JAMES LOEB, LL.D. EDITED BY fT. E. PAGE, C.H., LITT.D. litt.d. tE. CAPPS, PH.D., LL.D. tW. H. D. ROUSE, f.e.hist.soc. L. A. POST, L.H.D. E. H. WARMINGTON, m.a., LUCIAN V •^ LUCIAN WITH AN ENGLISH TRANSLATION BY A. M. HARMON OK YALE UNIVERSITY IN EIGHT VOLUMES V LONDON WILLIAM HEINEMANN LTD CAMBRIDGE, MASSACHUSETTS HARVARD UNIVERSITY PRESS MOMLXII f /. ! n ^1 First printed 1936 Reprinted 1955, 1962 Printed in Great Britain CONTENTS PAGE LIST OF LTTCIAN'S WORKS vii PREFATOEY NOTE xi THE PASSING OF PEBEORiNUS (Peregrinus) .... 1 THE RUNAWAYS {FugiUvt) 53 TOXARis, OR FRIENDSHIP (ToxaHs vd amiciHa) . 101 THE DANCE {Saltalio) 209 • LEXiPHANES (Lexiphanes) 291 THE EUNUCH (Eunuchiis) 329 ASTROLOGY {Astrologio) 347 THE MISTAKEN CRITIC {Pseudologista) 371 THE PARLIAMENT OF THE GODS {Deorutti concilhim) . 417 THE TYRANNICIDE (Tyrannicidj,) 443 DISOWNED (Abdicatvs) 475 INDEX 527 —A LIST OF LUCIAN'S WORKS SHOWING THEIR DIVISION INTO VOLUMES IN THIS EDITION Volume I Phalaris I and II—Hippias or the Bath—Dionysus Heracles—Amber or The Swans—The Fly—Nigrinus Demonax—The Hall—My Native Land—Octogenarians— True Story I and II—Slander—The Consonants at Law—The Carousal or The Lapiths. Volume II The Downward Journey or The Tyrant—Zeus Catechized —Zeus Rants—The Dream or The Cock—Prometheus—* Icaromenippus or The Sky-man—Timon or The Misanthrope —Charon or The Inspector—Philosophies for Sale. Volume HI The Dead Come to Life or The Fisherman—The Double Indictment or Trials by Jury—On Sacrifices—The Ignorant Book Collector—The Dream or Lucian's Career—The Parasite —The Lover of Lies—The Judgement of the Goddesses—On Salaried Posts in Great Houses. -

1 Divine Intervention and Disguise in Homer's Iliad Senior Thesis

Divine Intervention and Disguise in Homer’s Iliad Senior Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Undergraduate School of Arts and Sciences Brandeis University Undergraduate Program in Classical Studies Professor Joel Christensen, Advisor In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts By Joana Jankulla May 2018 Copyright by Joana Jankulla 1 Copyright by Joana Jankulla © 2018 2 Acknowledgements First and foremost, I would like to thank my advisor, Professor Joel Christensen. Thank you, Professor Christensen for guiding me through this process, expressing confidence in me, and being available whenever I had any questions or concerns. I would not have been able to complete this work without you. Secondly, I would like to thank Professor Ann Olga Koloski-Ostrow and Professor Cheryl Walker for reading my thesis and providing me with feedback. The Classics Department at Brandeis University has been an instrumental part of my growth in my four years as an undergraduate, and I am eternally thankful to all the professors and staff members in the department. Thank you to my friends, specifically Erica Theroux, Sarah Jousset, Anna Craven, Rachel Goldstein, Taylor McKinnon and Georgie Contreras for providing me with a lot of emotional support this year. I hope you all know how grateful I am for you as friends and how much I have appreciated your love this year. Thank you to my mom for FaceTiming me every time I was stressed about completing my thesis and encouraging me every step of the way. Finally, thank you to Ian Leeds for dropping everything and coming to me each time I needed it. -

The 'Trial by Water' in Greek Myth and Literature

Leeds International Classical Studies 7.1 (2008) ISSN 1477-3643 (http://www.leeds.ac.uk/classics/lics/) © Fiona McHardy The ‘trial by water’ in Greek myth and literature FIONA MCHARDY (ROEHAMPTON UNIVERSITY) ABSTRACT: This paper discusses the theme of casting ‘unchaste’ women into the sea as a punishment in Greek myth and literature. Particular focus will be given to the stories of Danaë, Augë, Aerope and Phronime, who are all depicted suffering this punishment at the hands of their fathers. While Seaford (1990) has emphasized the theme of imprisonment which occurs in some of the stories involving the ‘floating chest’, I turn my attention instead to the theme of the sea. The coincidence in these stories of the threat of drowning for apparent promiscuity or sexual impurity with the escape of those girls who are innocent can be explained by the phenomenon of the ‘trial by water’ as evidenced in Babylonian and other early law codes (cf. Glotz 1904). Further evidence for this theory can be found in ancient novels where the trial of the heroine for sexual purity is often a key theme. The significance of chastity in the myths and in Athenian society is central to understanding the story patterns. The interrelationship of mythic and social ideals is drawn out in the paper. This paper examines the punishment of ‘unchaste’ women in Greek myth and literature, in particular their representation in Euripides’ fragmentary Augë, Cretan Women and Danaë. My focus is on punishments involving the sea, where it is possible to discern two interrelated strands in the tales.1 The first strand involves an angry parent condemning an errant daughter to be cast into the sea with the intention of drowning her. -

Phoenix in the Iliad

University of Mary Washington Eagle Scholar Student Research Submissions Spring 5-4-2017 Phoenix in the Iliad Kati M. Justice Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.umw.edu/student_research Part of the Classics Commons Recommended Citation Justice, Kati M., "Phoenix in the Iliad" (2017). Student Research Submissions. 152. https://scholar.umw.edu/student_research/152 This Honors Project is brought to you for free and open access by Eagle Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Research Submissions by an authorized administrator of Eagle Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PHOENIX IN THE ILIAD An honors paper submitted to the Department of Classics, Philosophy, and Religion of the University of Mary Washington in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Departmental Honors Kati M. Justice May 2017 By signing your name below, you affirm that this work is the complete and final version of your paper submitted in partial fulfillment of a degree from the University of Mary Washington. You affirm the University of Mary Washington honor pledge: "I hereby declare upon my word of honor that I have neither given nor received unauthorized help on this work." Kati Justice 05/04/17 (digital signature) PHOENIX IN THE ILIAD Kati Justice Dr. Angela Pitts CLAS 485 April 24, 2017 2 Abstract This paper analyzes evidence to support the claim that Phoenix is an narratologically central and original Homeric character in the Iliad. Phoenix, the instructor of Achilles, tries to persuade Achilles to protect the ships of Achaeans during his speech. At the end of his speech, Phoenix tells Achilles about the story of Meleager which serves as a warning about waiting too long to fight the Trojans. -

The Arms of Achilles: Re-Exchange in the Iliad

The Arms of Achilles: Re-Exchange in the Iliad by Eirene Seiradaki A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of Classics University of Toronto © Copyright by Eirene Seiradaki (2014) “The Arms of Achilles: Re-Exchange in the Iliad ” Eirene Seiradaki Doctor of Philosophy Department of Classics University of Toronto 2014 Abstract This dissertation offers an interpretation of the re-exchange of the first set of Achilles’ arms in the Iliad by gift, loan, capture, and re-capture. Each transfer of the arms is examined in relation to the poem’s dramatic action, characterisation, and representation of social institutions and ethical values. Modern anthropological and economic approaches are employed in order to elucidate standard elements surrounding certain types of exchange. Nevertheless, the study primarily involves textual analysis of the Iliadic narratives recounting the circulation-process of Achilles’ arms, with frequent reference to the general context of Homeric exchange and re-exchange. The origin of the armour as a wedding gift to Peleus for his marriage to Thetis and its consequent bequest to Achilles signifies it as the hero’s inalienable possession and marks it as the symbol of his fate in the Iliad . Similarly to the armour, the spear, a gift of Cheiron to Peleus, is later inherited by his son. Achilles’ own bond to Cheiron makes this weapon another inalienable possession of the hero. As the centaur’s legacy to his pupil, the spear symbolises Achilles’ awareness of his coming death. In the present time of the Iliad , ii Achilles lends his armour to Patroclus under conditions that indicate his continuing ownership over his panoply and ensure the safe use of the divine weapons by his friend. -

THE PALACES of HOMER. IT Is Much to Be Regretted That

264 THE PALACES OF HOMER. THE PALACES OF HOMER. IT is much to be regretted that the invaluable researches of Schliemann, which have done so much to illuminate many fields of Homeric archaeology, help us but little in our recon- struction of the houses of Homeric chiefs. Both at Hissarlik and at Mycenae that indefatigable explorer laid bare the founda- tions or substructions of houses, large in comparison with those which surrounded them, which must probably have belonged to chiefs or kings. But the dwelling at Hissarlik belonged to a far ruder city than that of Homer,1 and in the foundations of walls near the Agora of Mycenae no clear plan can be made out. So it is also at Ithaca. Gell's description of the plan of the palace of Odysseus, a plan which he professed to be based on still existing remains on Mount Aetos in Ithaca, rests, as is now well known, on nothing but invention and imagination. Schliemann found indeed on the summit of that hill a small level platform of triangular form, which he conjectures to have been originally in size some 166 feet by 127 feet, and surrounded by a massive circuit-wall. And within the circuit he found remnants of six or seven Cyclopean buildings, which may have been chambers of one house.2 But there is nothing to lead us to suppose that these buildings belonged to the Homeric age; therefore for a restoration of the palace of that age they afford little or no material. Evidence of closer bearing is furnished by existing country- houses and caravanserais of the East, where things change so slowly. -

Euripides and Gender: the Difference the Fragments Make

Euripides and Gender: The Difference the Fragments Make Melissa Karen Anne Funke A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2013 Reading Committee: Ruby Blondell, Chair Deborah Kamen Olga Levaniouk Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Classics © Copyright 2013 Melissa Karen Anne Funke University of Washington Abstract Euripides and Gender: The Difference the Fragments Make Melissa Karen Anne Funke Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor Ruby Blondell Department of Classics Research on gender in Greek tragedy has traditionally focused on the extant plays, with only sporadic recourse to discussion of the many fragmentary plays for which we have evidence. This project aims to perform an extensive study of the sixty-two fragmentary plays of Euripides in order to provide a picture of his presentation of gender that is as full as possible. Beginning with an overview of the history of the collection and transmission of the fragments and an introduction to the study of gender in tragedy and Euripides’ extant plays, this project takes up the contexts in which the fragments are found and the supplementary information on plot and character (known as testimonia) as a guide in its analysis of the fragments themselves. These contexts include the fifth- century CE anthology of Stobaeus, who preserved over one third of Euripides’ fragments, and other late antique sources such as Clement’s Miscellanies, Plutarch’s Moralia, and Athenaeus’ Deipnosophistae. The sections on testimonia investigate sources ranging from the mythographers Hyginus and Apollodorus to Apulian pottery to a group of papyrus hypotheses known as the “Tales from Euripides”, with a special focus on plot-type, especially the rape-and-recognition and Potiphar’s wife storylines. -

The Women of Ovid's Ars Amatoria

THE WOMEN OF OVID’S ARS AMATORIA: NATURE OR CULTURE? The women of Ovid’s Ars Amatoria may well impress the readers of this poem as a highly ‘unnatural’ lot. They mince, pout, and posture through the three books of Ovid’s treatise on the lover’s art with the calculated elegance and studied poise of dancers in a minuet. Their appearance, however, is deceptive. Ἀ closer look exposes the cultivation of these feminae cultissimae as a fragile patina, literally only skin deep. In the following essay, we shall consider how and why this can be so. Before we can begin to penetrate the elegant surface of the women of Ovid’s poem it is first necessary to consider the context in which they appear and operate: the poem itself. Ovid’s Ars Amatoria is an exposition and celebration of erotic culture, amatory cultus which by the late first century at Rome had progressed (at least in some circles) far beyond the inept fumbling of the rustic past, but as yet awaited codification into a handbook of didactic precepts by a master of the art. Enter the praeceptor. Drawing on a vast store of personal experience, usus (AA 1.29),1 as well as objective observation, this professorial paragon codifies the lover’s art in canons which turn on artifice, inhibition, hypocracy, and sublimation. The praeceptor’s rules comprise a system for manipulating and transcending the natural erotic impulse, and as such are not only the description of a cultural process but are themselves a cultural product.2 *& Although the poet expresses certain reservations about some aspects of 1 All references to the text of the Ars Amatoria are indicated by the siglum AA and are according to the edition of E.J. -

I I I: Briseis. to Achilles

I I I: Briseis. to Achilles The character of Briseis is derived by Ovid from the Iliad. In that soQrce, however, the character of Briseis is scarcely developed and she is little more than a pivot around which the fabled wrath of Achilles is devdpped. While she may have been loved by Achilles in Homer's account, we should also note that for him the loss ofBriseis must surely have been perceived as an insult of the. gravest propor tions. We know very litde about Briseis and the charms she might have had in the eyes of Achilles; we only know that upon losing her Achilles retired from combat to his tent. In the Heroides, Briseis becomes a woman richly endowed with human feeling who grieves that she has not been reunited with the man she. loves, who fears that she will be supplanted by another, and who must now find her future life with those who destroyed her homeland, her family and her heritage. For Briseis the attraction identified u love is dangerously close to the fear of abandonment. She does not object so much to captivity as to the uncer~ty and instability that it has brought into her life. In this, Briseis echoes a theme which permeates the Heroidts: the lover and the beloved both seek to bring into their .lives a degree of permanence and changelessness that in reality is nearly impossible of attainment. But the situation of Bri~eis is still more tenuous. She is not only a pawn in a mysterious game being played out by characters superior to her in every way but she is also a barbarian.