UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Iliad Homer

The Iliad Homer BOOK I. How Agamemnon and Achilles fell out at the siege of Troy; and Achilles withdrew himself from battle, and won from Zeus a pledge that his wrong should be avenged on Agamemnon and the Achaians. Sing, goddess, the wrath of Achilles Peleus’ son, the ruinous wrath that brought on the Achaians woes innumerable, and hurled down into Hades many strong souls of heroes, and gave their bodies to be a prey to dogs and all winged fowls; and so the counsel of Zeus wrought out its accomplishment from the day when first strife parted Atreides king of men and noble Achilles. Who among the gods set the twain at strife and variance? Apollo, the son of Leto and of Zeus; for he in anger at the king sent a sore plague upon the host, so that the folk began to perish, because Atreides had done dishonour to Chryses the priest. For the priest had come to the Achaians’ fleet ships to win his daughter’s freedom, and brought a ransom beyond telling; and bare in his hands the fillet of Apollo the Far- darter upon a golden staff; and made his prayer unto all the Achaians, and most of all to the two sons of Atreus, orderers of the host; “Ye sons of Atreus and all ye well-greaved Achaians, now may the gods that dwell in the mansions of Olympus grant you to lay waste the city of Priam, and to fare happily homeward; only set ye my dear child free, and accept the ransom in reverence to the son of Zeus, far-darting Apollo.” The Iliad Homer Then all the other Achaians cried assent, to reverence the priest and accept his goodly ransom; yet the thing pleased not the heart of Agamemnon son of Atreus, but he roughly sent him away, and laid stern charge upon him, saying: “Let me not find thee, old man, amid the hollow ships, whether tarrying now or returning again hereafter, lest the staff and fillet of the god avail thee naught. -

HOMERIC-ILIAD.Pdf

Homeric Iliad Translated by Samuel Butler Revised by Soo-Young Kim, Kelly McCray, Gregory Nagy, and Timothy Power Contents Rhapsody 1 Rhapsody 2 Rhapsody 3 Rhapsody 4 Rhapsody 5 Rhapsody 6 Rhapsody 7 Rhapsody 8 Rhapsody 9 Rhapsody 10 Rhapsody 11 Rhapsody 12 Rhapsody 13 Rhapsody 14 Rhapsody 15 Rhapsody 16 Rhapsody 17 Rhapsody 18 Rhapsody 19 Rhapsody 20 Rhapsody 21 Rhapsody 22 Rhapsody 23 Rhapsody 24 Homeric Iliad Rhapsody 1 Translated by Samuel Butler Revised by Soo-Young Kim, Kelly McCray, Gregory Nagy, and Timothy Power [1] Anger [mēnis], goddess, sing it, of Achilles, son of Peleus— 2 disastrous [oulomenē] anger that made countless pains [algea] for the Achaeans, 3 and many steadfast lives [psūkhai] it drove down to Hādēs, 4 heroes’ lives, but their bodies it made prizes for dogs [5] and for all birds, and the Will of Zeus was reaching its fulfillment [telos]— 6 sing starting from the point where the two—I now see it—first had a falling out, engaging in strife [eris], 7 I mean, [Agamemnon] the son of Atreus, lord of men, and radiant Achilles. 8 So, which one of the gods was it who impelled the two to fight with each other in strife [eris]? 9 It was [Apollo] the son of Leto and of Zeus. For he [= Apollo], infuriated at the king [= Agamemnon], [10] caused an evil disease to arise throughout the mass of warriors, and the people were getting destroyed, because the son of Atreus had dishonored Khrysēs his priest. Now Khrysēs had come to the ships of the Achaeans to free his daughter, and had brought with him a great ransom [apoina]: moreover he bore in his hand the scepter of Apollo wreathed with a suppliant’s wreath [15] and he besought the Achaeans, but most of all the two sons of Atreus, who were their chiefs. -

Ms. Legrange's Lesson Plans

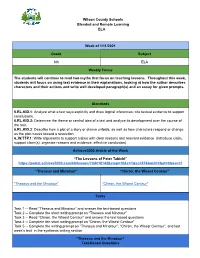

Wilson County Schools Blended and Remote Learning ELA Week of 1/11/2021 Grade Subject 6th ELA Weekly Focus The students will continue to read two myths that focus on teaching lessons. Throughout this week, students will focus on using text evidence in their explanations, looking at how the author describes characters and their actions and write well developed paragraph(s) and an essay for given prompts. Standards 6.RL.KID.1: Analyze what a text says explicitly and draw logical inferences; cite textual evidence to support conclusions. 6.RL.KID.2: Determine the theme or central idea of a text and analyze its development over the course of the text. 6.RL.KID.3: Describe how a plot of a story or drama unfolds, as well as how characters respond or change as the plot moves toward a resolution. 6..W.TTP.1 : Write arguments to support claims with clear reasons and relevant evidence (introduce claim, support claim(s), organize reasons and evidence, effective conclusion). Achieve3000 Article of the Week “The Lessons of Peter Tabichi” https://portal.achieve3000.com/kb/lesson/?lid=18142&step=10&c=1&sc=276&oid=0&ot=0&asn=1 “Theseus and Minotaur” “Chiron, the Wisest Centaur” "Theseus and the Minotaur" "Chiron, the Wisest Centaur" Tasks Task 1 -- Read “Theseus and Minotaur” and answer the text-based questions Task 2 -- Complete the short writing prompt on “Theseus and Minotaur” Task 3 -- Read ”Chiron, the Wisest Centaur” and answer the text-based questions Task 4 -- Complete the short writing prompt on “Chiron, the Wisest Centaur” Task 5 -- Complete the writing prompt on “Theseus and Minotaur”, “Chiron, the Wisest Centaur”, and last week’s text in the synthesis writing section. -

Iliad Teacher Sample

CONTENTS Teaching Guidelines ...................................................4 Appendix Book 1: The Anger of Achilles ...................................6 Genealogies ...............................................................57 Book 2: Before Battle ................................................8 Alternate Names in Homer’s Iliad ..............................58 Book 3: Dueling .........................................................10 The Friends and Foes of Homer’s Iliad ......................59 Book 4: From Truce to War ........................................12 Weaponry and Armor in Homer..................................61 Book 5: Diomed’s Day ...............................................14 Ship Terminology in Homer .......................................63 Book 6: Tides of War .................................................16 Character References in the Iliad ...............................65 Book 7: A Duel, a Truce, a Wall .................................18 Iliad Tests & Keys .....................................................67 Book 8: Zeus Takes Charge ........................................20 Book 9: Agamemnon’s Day ........................................22 Book 10: Spies ...........................................................24 Book 11: The Wounded ..............................................26 Book 12: Breach ........................................................28 Book 13: Tug of War ..................................................30 Book 14: Return to the Fray .......................................32 -

MONEY and the EARLY GREEK MIND: Homer, Philosophy, Tragedy

This page intentionally left blank MONEY AND THE EARLY GREEK MIND How were the Greeks of the sixth century bc able to invent philosophy and tragedy? In this book Richard Seaford argues that a large part of the answer can be found in another momentous development, the invention and rapid spread of coinage, which produced the first ever thoroughly monetised society. By transforming social relations, monetisation contributed to the ideas of the universe as an impersonal system (presocratic philosophy) and of the individual alienated from his own kin and from the gods (in tragedy). Seaford argues that an important precondition for this monetisation was the Greek practice of animal sacrifice, as represented in Homeric epic, which describes a premonetary world on the point of producing money. This book combines social history, economic anthropology, numismatics and the close reading of literary, inscriptional, and philosophical texts. Questioning the origins and shaping force of Greek philosophy, this is a major book with wide appeal. richard seaford is Professor of Greek Literature at the University of Exeter. He is the author of commentaries on Euripides’ Cyclops (1984) and Bacchae (1996) and of Reciprocity and Ritual: Homer and Tragedy in the Developing City-State (1994). MONEY AND THE EARLY GREEK MIND Homer, Philosophy, Tragedy RICHARD SEAFORD cambridge university press Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, Madrid, Cape Town, Singapore, São Paulo Cambridge University Press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge cb2 2ru, UK Published in the United States of America by Cambridge University Press, New York www.cambridge.org Information on this title: www.cambridge.org/9780521832281 © Richard Seaford 2004 This publication is in copyright. -

New Approaches to the Temple of Zeus at Olympia

New Approaches to the Temple of Zeus at Olympia New Approaches to the Temple of Zeus at Olympia Proceedings of the First Olympia-Seminar 8th-10th May 2014 Edited by András Patay-Horváth New Approaches to the Temple of Zeus at Olympia: Proceedings of the First Olympia-Seminar 8th-10th May 2014 Edited by András Patay-Horváth This book first published 2015 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2015 by András Patay-Horváth and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-7816-2 ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-7816-6 FOR J. GY. SZILÁGYI TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface ......................................................................................................... x List of Illustrations and Tables .................................................................. xii Abbreviations ............................................................................................ xx Introduction ................................................................................................ 1 Adopting a New Approach to the Temple and its Sculptural Decoration András Patay-Horváth Part I: Architecture Chapter One .............................................................................................. -

Inventory of Dual Forms in the Iliad

Carolin Hahnemann, Professor of Classics, Kenyon College, Gambier, OH 43022, USA [email protected] INVENTORY OF DUAL FORMS IN THE ILIAD This table follows the text of West’s Teubner edition; only occasionally does it record a dual reading reported in the critical apparatus. Since my primary interests concerns the different types of referents that take dual forms, in the fourth column after the name of the speaker (in capital letters) I distinguish the following types: Abstract Concepts Measure Objects Bodypart Nature Animal Persons Within the last group I have tentatively sought to establish the following subgroups: Sexual Couple Parent and Child Sibling Pair Equals in Action General Collective Many entries contain additional notes. Regarding these it is important to know that I started to add the label “formula” only late; hence it is very often missing. By “necessary dual” I mean forms for which no plural alternative exists such as the numeral. I can see two kinds of additional information that would help to provide a more well-rounded picture of the use of the dual in the Iliad. (1) Morphological analysis of each dual form would show the spread of dual forms according to part of speech as well as case, gender and declension for nouns and person, tense, mood, voice for verbs. (2) Tracking of the sequence of dual and plural per passage would give a sense of high versus low incidence of dual forms and also show whether dual forms gravitate toward are particular position within the passage such as its beginning or end. It is my hope that the table may prove useful to other scholars and will gladly provide microsoft versions for anybody who would like to adapt or build on the existing material as part of his or her own investigation (see email address in header). -

The Parthenon, Part I: from Its Multiple Beginnings to 432 BCE"

1 THE FORTNIGHTLY CLUB Of REDLANDS, CALIFORNIA Founded 24 January 1895 Meeting Number 1856 March 13, 2014 "The Parthenon, Part I: From its Multiple Beginnings to 432 BCE" Bill McDonald Assembly Room, A. K. Smiley Public Library 2 [1] (Numbers in red catalog the slides) Fortnightly Talk #6 From Herekleides of Crete, in the 3rd century BCE: “The most beautiful things in the world are there [in Athens}… The sumptuous temple of Athena stands out, and is well worth a look. It is called the Parthenon and it is on the hill above the theatre. It makes a tremendous impression on visitors.” Reporter: Did you visit the Parthenon during your trip to Greece?” Shaq: “I can’t really remember the names of the clubs we went to.” Architects, aesthetes, grand tour-takers from England, France and Germany all came to Rome in the 3rd quarter of the 18th century, where they developed on uneven evidence a newly austere view of the classical world that in turn produced the Greek revival across northern Europe and in America. Johann Joachim Winckelmann (1717 – 1768) [2], a self-made scholar of ancient Greek language and texts, was their unofficial high priest. In 1755 Winckelmann arrived for the first time in Rome, where thanks not only to his brilliant publications but also to a recent and, shall we say, a timely conversion to Catholicism, he was admitted by papal authorities to the Vatican galleries and storerooms (his friend Goethe said that Winckelmann was really “a pagan”). His contemporaries in Rome saw Greek civilization as a primitive source for Roman art, and had never troubled to isolate Greek art from its successor; Winckelmann reversed that, making Greek art and 3 architecture, especially sculpture—and especially of the young male form that he especially admired—not only distinctive in its own right but the font of the greatest Western art. -

1 Divine Intervention and Disguise in Homer's Iliad Senior Thesis

Divine Intervention and Disguise in Homer’s Iliad Senior Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Undergraduate School of Arts and Sciences Brandeis University Undergraduate Program in Classical Studies Professor Joel Christensen, Advisor In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts By Joana Jankulla May 2018 Copyright by Joana Jankulla 1 Copyright by Joana Jankulla © 2018 2 Acknowledgements First and foremost, I would like to thank my advisor, Professor Joel Christensen. Thank you, Professor Christensen for guiding me through this process, expressing confidence in me, and being available whenever I had any questions or concerns. I would not have been able to complete this work without you. Secondly, I would like to thank Professor Ann Olga Koloski-Ostrow and Professor Cheryl Walker for reading my thesis and providing me with feedback. The Classics Department at Brandeis University has been an instrumental part of my growth in my four years as an undergraduate, and I am eternally thankful to all the professors and staff members in the department. Thank you to my friends, specifically Erica Theroux, Sarah Jousset, Anna Craven, Rachel Goldstein, Taylor McKinnon and Georgie Contreras for providing me with a lot of emotional support this year. I hope you all know how grateful I am for you as friends and how much I have appreciated your love this year. Thank you to my mom for FaceTiming me every time I was stressed about completing my thesis and encouraging me every step of the way. Finally, thank you to Ian Leeds for dropping everything and coming to me each time I needed it. -

1 Reading Athenaios' Epigraphical Hymn to Apollo: Critical Edition And

Reading Athenaios’ Epigraphical Hymn to Apollo: Critical Edition and Commentaries DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Corey M. Hackworth Graduate Program in Greek and Latin The Ohio State University 2015 Dissertation Committee: Fritz Graf, Advisor Benjamin Acosta-Hughes Carolina López-Ruiz 1 Copyright by Corey M. Hackworth 2015 2 Abstract This dissertation is a study of the Epigraphical Hymn to Apollo that was found at Delphi in 1893, and since attributed to Athenaios. It is believed to have been performed as part of the Athenian Pythaïdes festival in the year 128/7 BCE. After a brief introduction to the hymn, I provide a survey and history of the most important editions of the text. I offer a new critical edition equipped with a detailed apparatus. This is followed by an extended epigraphical commentary which aims to describe the history of, and arguments for and and against, readings of the text as well as proposed supplements and restorations. The guiding principle of this edition is a conservative one—to indicate where there is uncertainty, and to avoid relying on other, similar, texts as a resource for textual restoration. A commentary follows, which traces word usage and history, in an attempt to explore how an audience might have responded to the various choices of vocabulary employed throughout the text. Emphasis is placed on Athenaios’ predilection to utilize new words, as well as words that are non-traditional for Apolline narrative. The commentary considers what role prior word usage (texts) may have played as intertexts, or sources of poetic resonance in the ears of an audience. -

Virgil, Aeneid 11 (Pallas & Camilla) 1–224, 498–521, 532–96, 648–89, 725–835 G

Virgil, Aeneid 11 (Pallas & Camilla) 1–224, 498–521, 532–96, 648–89, 725–835 G Latin text, study aids with vocabulary, and commentary ILDENHARD INGO GILDENHARD AND JOHN HENDERSON A dead boy (Pallas) and the death of a girl (Camilla) loom over the opening and the closing part of the eleventh book of the Aeneid. Following the savage slaughter in Aeneid 10, the AND book opens in a mournful mood as the warring parti es revisit yesterday’s killing fi elds to att end to their dead. One casualty in parti cular commands att enti on: Aeneas’ protégé H Pallas, killed and despoiled by Turnus in the previous book. His death plunges his father ENDERSON Evander and his surrogate father Aeneas into heart-rending despair – and helps set up the foundati onal act of sacrifi cial brutality that caps the poem, when Aeneas seeks to avenge Pallas by slaying Turnus in wrathful fury. Turnus’ departure from the living is prefi gured by that of his ally Camilla, a maiden schooled in the marti al arts, who sets the mold for warrior princesses such as Xena and Wonder Woman. In the fi nal third of Aeneid 11, she wreaks havoc not just on the batt lefi eld but on gender stereotypes and the conventi ons of the epic genre, before she too succumbs to a premature death. In the porti ons of the book selected for discussion here, Virgil off ers some of his most emoti ve (and disturbing) meditati ons on the tragic nature of human existence – but also knows how to lighten the mood with a bit of drag. -

Lectures on Greek Poetry

Lectures on Greek Poetry 1 2 ADAM MICKIEWICZ UNIVERSITY IN POZNAŃ CLASSICAL PHILOLOGY SERIES NO. 35 GERSON SCHADE Lectures on Greek Poetry POZNAŃ 2016 3 ABSTRACT. Gerson Schade, Lectures on Greek Poetry [Wykłady o poezji greckiej]. Adam Mickiewicz University Press. Poznań 2016. Pp. 226. Classical Philology Series No. 35. ISBN 978-83-232-3108-0. ISSN 0554-8160. Text in English with a summary in German. The series of lectures contained in this volume were written for students at Adam Mic- kiewicz University. A first group of these lectures are intended to serve as an introduc- tion to Greek poetry of the archaic, classical and pre-Hellenistic age. They treat a selection of texts, ranging from the eighth to the fourth century BC. A second group of these lec- tures focuses on Homer’s Iliad: while the whole work is treated, the lectures follow the story of Achilles, which is developed mainly in five books. All texts are provided in trans- lation, and secondary literature is discussed and used to make the texts more accessible for young students interested in poetry. The lectures introduce to some of the main issues that characterise the texts, such as their relationship to their primary audience, the impact of orality, and the influence of the eastern poetic tradition on the Greeks. Where appro- priate, the lectures also treat the interrelation between various texts, their intertextuality. They try to answer the questions of how poetry did work then, and why these texts do matter for the European poetic tradition. Schade Gerson, Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań, Faculty of Polish and Classical Philology, Institute of Classical Philology, Fredry 10, 61-701 Poznań, Poland Reviewers: prof.