Presentation of the Ancient Macedonian Kings and Their Court Still Endures, in Spite of Recent Notes on the Use of ‘Artifice’ in Key Ancient Accounts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Dialect of Elis and Its Position Within the Greek Dialectological System MA-Thesis for the Master Classics and Ancient Civilisations

The dialect of Elis and its position within the Greek dialectological system MA-thesis for the Master Classics and Ancient Civilisations Le site antique d’Olympie, illustration taken from Minon 2007 : 559 by M.J. van der Velden BA supervisors: dr. L. van Beek dr. A. Rademaker 2015-17 Universiteit Leiden Table of contents i. Acknowledgements ii. List of abbreviations 0. Introduction 1. The dialect features of Elean 1.1 West Greek features 1.1.1 West Greek phonological features 1.1.2 West Greek morphological features 1.1.3 Conclusion 1.2 Northwest Greek features 1.2.1 Northwest Greek phonological features 1.2.2 Northwest Greek morphological features 1.2.3 Conclusion 1.3 Features in common with various other dialects 1.3.1 Phonological features in common with various other dialects 1.3.2 Morphological features in common with various other dialects 1.3.3 Conclusion 1.4 Specifically Elean features 1.4.1 Specifically Elean phonological features 1.4.2 Specifically Elean morphological features 1.4.3 Conclusion 1.5 General conclusion 2. Evaluation 2.1 The consonant stem accusative plural in -ες 2.2 The consonant stem dative plural endings -οις and -εσσι 2.3 The middle participle in /-ēmenos/ 2.4 The development *ē > ǟ 2.5 The development *ӗ > α 2.6 The development *i > ε 3. Conclusion 4. Bibliography 2 Acknowledgements First of all, I would like to express my deepest gratitude towards Lucien van Beek for supervising my work, without whose help, comments and – at times necessary – incitations this study would not have reached its current shape, as well as towards Adriaan Rademaker for carefully reading my work and sharing his remarks. -

Download The

THE CONCEPT OF SACRED WAR IN ANCIENT GREECE By FRANCES ANNE SKOCZYLAS B.A., McGill University, 1985 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Department of Classics) We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA August 1987 ® Frances Anne Skoczylas, 1987 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of CLASSICS The University of British Columbia 1956 Main Mall Vancouver, Canada V6T 1Y3 Date AUtt-UST 5r 1Q87 ii ABSTRACT This thesis will trace the origin and development of the term "Sacred War" in the corpus of extant Greek literature. This term has been commonly applied by modern scholars to four wars which took place in ancient Greece between- the sixth and fourth centuries B. C. The modern use of "the attribute "Sacred War" to refer to these four wars in particular raises two questions. First, did the ancient historians give all four of these wars the title "Sacred War?" And second, what justified the use of this title only for certain conflicts? In order to resolve the first of these questions, it is necessary to examine in what terms the ancient historians referred to these wars. -

Ancient History Sourcebook: 11Th Brittanica: Sparta SPARTA an Ancient City in Greece, the Capital of Laconia and the Most Powerful State of the Peloponnese

Ancient History Sourcebook: 11th Brittanica: Sparta SPARTA AN ancient city in Greece, the capital of Laconia and the most powerful state of the Peloponnese. The city lay at the northern end of the central Laconian plain, on the right bank of the river Eurotas, a little south of the point where it is joined by its largest tributary, the Oenus (mount Kelefina). The site is admirably fitted by nature to guard the only routes by which an army can penetrate Laconia from the land side, the Oenus and Eurotas valleys leading from Arcadia, its northern neighbour, and the Langada Pass over Mt Taygetus connecting Laconia and Messenia. At the same time its distance from the sea-Sparta is 27 m. from its seaport, Gythium, made it invulnerable to a maritime attack. I.-HISTORY Prehistoric Period.-Tradition relates that Sparta was founded by Lacedaemon, son of Zeus and Taygete, who called the city after the name of his wife, the daughter of Eurotas. But Amyclae and Therapne (Therapnae) seem to have been in early times of greater importance than Sparta, the former a Minyan foundation a few miles to the south of Sparta, the latter probably the Achaean capital of Laconia and the seat of Menelaus, Agamemnon's younger brother. Eighty years after the Trojan War, according to the traditional chronology, the Dorian migration took place. A band of Dorians united with a body of Aetolians to cross the Corinthian Gulf and invade the Peloponnese from the northwest. The Aetolians settled in Elis, the Dorians pushed up to the headwaters of the Alpheus, where they divided into two forces, one of which under Cresphontes invaded and later subdued Messenia, while the other, led by Aristodemus or, according to another version, by his twin sons Eurysthenes and Procles, made its way down the Eurotas were new settlements were formed and gained Sparta, which became the Dorian capital of Laconia. -

Ms. Legrange's Lesson Plans

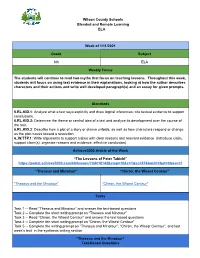

Wilson County Schools Blended and Remote Learning ELA Week of 1/11/2021 Grade Subject 6th ELA Weekly Focus The students will continue to read two myths that focus on teaching lessons. Throughout this week, students will focus on using text evidence in their explanations, looking at how the author describes characters and their actions and write well developed paragraph(s) and an essay for given prompts. Standards 6.RL.KID.1: Analyze what a text says explicitly and draw logical inferences; cite textual evidence to support conclusions. 6.RL.KID.2: Determine the theme or central idea of a text and analyze its development over the course of the text. 6.RL.KID.3: Describe how a plot of a story or drama unfolds, as well as how characters respond or change as the plot moves toward a resolution. 6..W.TTP.1 : Write arguments to support claims with clear reasons and relevant evidence (introduce claim, support claim(s), organize reasons and evidence, effective conclusion). Achieve3000 Article of the Week “The Lessons of Peter Tabichi” https://portal.achieve3000.com/kb/lesson/?lid=18142&step=10&c=1&sc=276&oid=0&ot=0&asn=1 “Theseus and Minotaur” “Chiron, the Wisest Centaur” "Theseus and the Minotaur" "Chiron, the Wisest Centaur" Tasks Task 1 -- Read “Theseus and Minotaur” and answer the text-based questions Task 2 -- Complete the short writing prompt on “Theseus and Minotaur” Task 3 -- Read ”Chiron, the Wisest Centaur” and answer the text-based questions Task 4 -- Complete the short writing prompt on “Chiron, the Wisest Centaur” Task 5 -- Complete the writing prompt on “Theseus and Minotaur”, “Chiron, the Wisest Centaur”, and last week’s text in the synthesis writing section. -

My Frends Are Animals Study Guide

STUDY GUIDE This Study Guide includes suggestions about preparing your students for a live theatre performance in order to help them take more from the experience. Included is information and ideas on how to use the performance to enhance aspects of your education curriculum: with exercises that respond to the themes presented in the performance and the dramatic elements. Please copy and distribute this guide to your fellow teachers. BOOKING INFORMATION Please contact the Booking Coordinator for more information. Local: 604 669 0631 Toll Free: 1 866 294 7943 Email: [email protected] CONTENTS Synopsis 3 Origins of the Story 3 About Babelle Theatre 3 Themes 4 Curriculum Connections: Arts Education 4 Social Studies 5 English Language Arts 6 Activities: Pre-Performance 7 Post-Performance 8 About Axis 11 Appendix 12 Characters 12 Vocabulary 12 Pantomime 15 CREDITS » Written by James Gordon King » Directed by Marie Farsi » Dramaturgy by Chris McGregor » Production Design by Jessica Oostergo » Puppets Design by Jeny Cassady » Lighting Design by Mimi Abrahams » Sound Design by Patrick Boudreau » Production Design Assistant Megan Veaudry » Stage Management by Aidan Hammond » Performed by Caitlin McFarlane, Meaghan Chenosky, Sabrina Vellani, Tyrone Savage Babelle Theatre Company ~ Axis Theatre Company 1. SYNOPSIS An all-ages romp from the city into the wild A bear wanders from the mountains into the city and the natural boundaries are flipped! Suddenly, we’re in a dream-like world where a misfit teenager named Jo becomes a ‘wild human’ – having to outrun mobs of agitated animals and escape human conservation officers in order to find her way home. -

Sage Is , Based Pressure E Final Out- Rned by , : Hearts, Could Persuade

Xerxes' War 137 136 Herodotus Book 7 a match for three Greeks. The same is true of my fellow Spartans. fallen to the naval power of the invader. So the Spartans would have They are the equal of any men when they fight alone; fighting to stood alone, and in their lone stand they would have performed gether, they surpass all other men. For they are free, but not entirely mighty deeds and died nobly. Either that or, seeing the other Greeks free: They obey a master called Law, and they fear this master much going over to the Persians, they would have come to terms with more than your men fear you. They do whatever it commands them Xerxes. Thus, in either case, Greece would have been subjugated by the Persians, for I cannot see what possible use it would have been to to do, and its commands are always the same: Not to retreat from the fortify the Isthmus if the king had had mastery over the sea. battlefield even when badly outnumbered; to stay in formation and either conquer or die. So if anyone were to say that the Athenians were saviors of "If this talk seems like nonsense to you, then let me stay silent Greece, he would not be far off the truth. For it was the Athenians who held the scales in balance; whichever side they espoused would henceforth; I spoke only under compulsion as it is. In any case, sire, I be sure to prevail. It was they who, choosing to maintain the freedom hope all turns out as you wish." of Greece, roused the rest of the Greeks who had not submitted, and [7.105] That was Demaratus' response. -

1 Divine Intervention and Disguise in Homer's Iliad Senior Thesis

Divine Intervention and Disguise in Homer’s Iliad Senior Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Undergraduate School of Arts and Sciences Brandeis University Undergraduate Program in Classical Studies Professor Joel Christensen, Advisor In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts By Joana Jankulla May 2018 Copyright by Joana Jankulla 1 Copyright by Joana Jankulla © 2018 2 Acknowledgements First and foremost, I would like to thank my advisor, Professor Joel Christensen. Thank you, Professor Christensen for guiding me through this process, expressing confidence in me, and being available whenever I had any questions or concerns. I would not have been able to complete this work without you. Secondly, I would like to thank Professor Ann Olga Koloski-Ostrow and Professor Cheryl Walker for reading my thesis and providing me with feedback. The Classics Department at Brandeis University has been an instrumental part of my growth in my four years as an undergraduate, and I am eternally thankful to all the professors and staff members in the department. Thank you to my friends, specifically Erica Theroux, Sarah Jousset, Anna Craven, Rachel Goldstein, Taylor McKinnon and Georgie Contreras for providing me with a lot of emotional support this year. I hope you all know how grateful I am for you as friends and how much I have appreciated your love this year. Thank you to my mom for FaceTiming me every time I was stressed about completing my thesis and encouraging me every step of the way. Finally, thank you to Ian Leeds for dropping everything and coming to me each time I needed it. -

Lucan's Natural Questions: Landscape and Geography in the Bellum Civile Laura Zientek a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulf

Lucan’s Natural Questions: Landscape and Geography in the Bellum Civile Laura Zientek A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2014 Reading Committee: Catherine Connors, Chair Alain Gowing Stephen Hinds Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Classics © Copyright 2014 Laura Zientek University of Washington Abstract Lucan’s Natural Questions: Landscape and Geography in the Bellum Civile Laura Zientek Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor Catherine Connors Department of Classics This dissertation is an analysis of the role of landscape and the natural world in Lucan’s Bellum Civile. I investigate digressions and excurses on mountains, rivers, and certain myths associated aetiologically with the land, and demonstrate how Stoic physics and cosmology – in particular the concepts of cosmic (dis)order, collapse, and conflagration – play a role in the way Lucan writes about the landscape in the context of a civil war poem. Building on previous analyses of the Bellum Civile that provide background on its literary context (Ahl, 1976), on Lucan’s poetic technique (Masters, 1992), and on landscape in Roman literature (Spencer, 2010), I approach Lucan’s depiction of the natural world by focusing on the mutual effect of humanity and landscape on each other. Thus, hardships posed by the land against characters like Caesar and Cato, gloomy and threatening atmospheres, and dangerous or unusual weather phenomena all have places in my study. I also explore how Lucan’s landscapes engage with the tropes of the locus amoenus or horridus (Schiesaro, 2006) and elements of the sublime (Day, 2013). -

Meet the Philosophers of Ancient Greece

Meet the Philosophers of Ancient Greece Everything You Always Wanted to Know About Ancient Greek Philosophy but didn’t Know Who to Ask Edited by Patricia F. O’Grady MEET THE PHILOSOPHERS OF ANCIENT GREECE Dedicated to the memory of Panagiotis, a humble man, who found pleasure when reading about the philosophers of Ancient Greece Meet the Philosophers of Ancient Greece Everything you always wanted to know about Ancient Greek philosophy but didn’t know who to ask Edited by PATRICIA F. O’GRADY Flinders University of South Australia © Patricia F. O’Grady 2005 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the publisher. Patricia F. O’Grady has asserted her right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identi.ed as the editor of this work. Published by Ashgate Publishing Limited Ashgate Publishing Company Wey Court East Suite 420 Union Road 101 Cherry Street Farnham Burlington Surrey, GU9 7PT VT 05401-4405 England USA Ashgate website: http://www.ashgate.com British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Meet the philosophers of ancient Greece: everything you always wanted to know about ancient Greek philosophy but didn’t know who to ask 1. Philosophy, Ancient 2. Philosophers – Greece 3. Greece – Intellectual life – To 146 B.C. I. O’Grady, Patricia F. 180 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Meet the philosophers of ancient Greece: everything you always wanted to know about ancient Greek philosophy but didn’t know who to ask / Patricia F. -

Greek Mythology

Greek Mythology The Creation Myth “First Chaos came into being, next wide bosomed Gaea(Earth), Tartarus and Eros (Love). From Chaos came forth Erebus and black Night. Of Night were born Aether and Day (whom she brought forth after intercourse with Erebus), and Doom, Fate, Death, sleep, Dreams; also, though she lay with none, the Hesperides and Blame and Woe and the Fates, and Nemesis to afflict mortal men, and Deceit, Friendship, Age and Strife, which also had gloomy offspring.”[11] “And Earth first bore starry Heaven (Uranus), equal to herself to cover her on every side and to be an ever-sure abiding place for the blessed gods. And earth brought forth, without intercourse of love, the Hills, haunts of the Nymphs and the fruitless sea with his raging swell.”[11] Heaven “gazing down fondly at her (Earth) from the mountains he showered fertile rain upon her secret clefts, and she bore grass flowers, and trees, with the beasts and birds proper to each. This same rain made the rivers flow and filled the hollow places with the water, so that lakes and seas came into being.”[12] The Titans and the Giants “Her (Earth) first children (with heaven) of Semi-human form were the hundred-handed giants Briareus, Gyges, and Cottus. Next appeared the three wild, one-eyed Cyclopes, builders of gigantic walls and master-smiths…..Their names were Brontes, Steropes, and Arges.”[12] Next came the “Titans: Oceanus, Hypenon, Iapetus, Themis, Memory (Mnemosyne), Phoebe also Tethys, and Cronus the wily—youngest and most terrible of her children.”[11] “Cronus hated his lusty sire Heaven (Uranus). -

A HISTORY of the PELASGIAN THEORY. FEW Peoples Of

A HISTORY OF THE PELASGIAN THEORY. FEW peoples of the ancient world have given rise to so much controversy as the Pelasgians; and of few, after some centuries of discussion, is so little clearly established. Like the Phoenicians, the Celts, and of recent years the Teutons, they have been a peg upon which to hang all sorts of speculation ; and whenever an inconvenient circumstance has deranged the symmetry of a theory, it has been safe to ' call it Pelasgian and pass on.' One main reason for this ill-repute, into which the Pelasgian name has fallen, has been the very uncritical fashion in which the ancient statements about the Pelasgians have commonly been mishandled. It has been the custom to treat passages from Homer, from Herodotus, from Ephorus, and from Pausanias, as if they were so many interchangeable bricks to build up the speculative edifice; as if it needed no proof that genealogies found sum- marized in Pausanias or Apollodorus ' were taken by them from poems of the same class with the Theogony, or from ancient treatises, or from prevalent opinions ;' as if, further, ' if we find them mentioning the Pelasgian nation, they do at all events belong to an age when that name and people had nothing of the mystery which they bore to the eyes of the later Greeks, for instance of Strabo;' and as though (in the same passage) a statement of Stephanus of Byzantium about Pelasgians in Italy ' were evidence to the same effect, perfectly unexceptionable and as strictly historical as the case will admit of 1 No one doubts, of course, either that popular tradition may transmit, or that late writers may transcribe, statements which come from very early, and even from contemporary sources. -

Bearing Razors and Swords: Paracomedy in Euripides’ Orestes

%HDULQJ5D]RUVDQG6ZRUGV3DUDFRPHG\LQ(XULSLGHV· 2UHVWHV &UDLJ-HQG]D $PHULFDQ-RXUQDORI3KLORORJ\9ROXPH1XPEHU :KROH1XPEHU )DOOSS $UWLFOH 3XEOLVKHGE\-RKQV+RSNLQV8QLYHUVLW\3UHVV '2, KWWSVGRLRUJDMS )RUDGGLWLRQDOLQIRUPDWLRQDERXWWKLVDUWLFOH KWWSVPXVHMKXHGXDUWLFOH Access provided by University of Kansas Libraries (5 Dec 2016 18:13 GMT) BEARING RAZORS AND SWORDS: PARACOMEDY IN EURIPIDES’ ORESTES CRAIG JENDZA Abstract. In this article, I trace a nuanced interchange between Euripides’ Helen, Aristophanes’ Thesmophoriazusae, and Euripides’ Orestes that contains a previ- ously overlooked example of Aristophanic paratragedy and Euripides’ paracomic response. I argue that the escape plot from Helen, in which Menelaus and Helen flee with “sword-bearing” men ξιφηφόρος( ), was co-opted in Thesmophoriazusae, when Aristophanes staged Euripides escaping with a man described as “being a razor-bearer” (ξυροφορέω). Furthermore, I suggest that Euripides re-appropriates this parody by escalating the quantity of sword-bearing men in Orestes, suggest- ing a dynamic poetic rivalry between Aristophanes and Euripides. Additionally, I delineate a methodology for evaluating instances of paracomedy. PARATRAGEDY, COMEDY’S AppROPRIATION OF LINES, SCENES, AND DRAMATURGY FROM TRAGEDY, constitutes a source of the genre’s authority (Foley 1988; Platter 2007), a source of the genre’s identity as a literary underdog in comparison to tragedy (Rosen 2005), and a source of its humor either through subverting or ridiculing tragedy (Silk 1993; Robson 2009, 108–13) or through audience detection and identification of quotations (Wright 2012, 145–50).1 The converse relationship between 1 Rau 1967 marks the beginning of serious investigation into paratragedy by analyz- ing numerous comic scenes that are modeled on tragic ones and providing a database, with hundreds of examples, of tragic lines that Aristophanes parodies.