(Im)Mobility and Mediterranean Migrations: Journeys “Between the Pleasures of Wealth and the Desires of the Poor”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Laila Lalami: Narrating North African Migration to Europe

Laila Lalami: Narrating North African Migration to Europe CHRISTIÁN H. RICCI UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, MERCED Introduction aila Lalami, author of three novels—Hope and Other Dangerous Pursuits L(2005), Secret Son (2009), and The Moor’s Account (2014)—and several short stories, has been considered the most important Moroccan author writ- ing in English; her work has been translated into more than eleven languages (Mehta 117). Compelled to write in a language that is not her mother tongue, Lalami’s narrations constitute a form of diasporic writing from within. She succeeds in defying not only the visual and cultural vilification of Muslims, but also the prevailing neo-orientalist concept of Muslim women’s writing as exclusively victim or escapee narratives. Up to now, the focus of most Mo- roccan migration stories “has been on male migrants as individuals, without reference to women, who nowadays constitute about 50% of international migration. This has led to the neglect of women in migration theories” (Ennaji and Sadiqui 8, 14). As the result of labor migration and family reunification (twenty percent of Moroccan citizens now live in Europe), combined with the geo- graphic proximity of Europe and North Africa, the notion of a national or “native” literature is slightly unstable with regard to Morocco. Its literary production is not limited by the borders of the nation-state, but spills over to the European continent, where the largest Moroccan-descent communities are in France (over a million), Spain (800,000), the Netherlands (370,000), and Belgium (200,000). Contemporary Moroccan literature does more than criticize and reb- el against the Makhzen, a term that originally refers to the storehouse where tribute and taxes to the sultan were stowed; through the centuries Makhzen has come to signify not just the power holders in Morocco, but how power has been exercised throughout society. -

Download Book

Arab American Literary Fictions, Cultures, and Politics American Literature Readings in the 21st Century Series Editor: Linda Wagner-Martin American Literature Readings in the 21st Century publishes works by contemporary critics that help shape critical opinion regarding literature of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries in the United States. Published by Palgrave Macmillan Freak Shows in Modern American Imagination: Constructing the Damaged Body from Willa Cather to Truman Capote By Thomas Fahy Arab American Literary Fictions, Cultures, and Politics By Steven Salaita Women and Race in Contemporary U.S. Writing: From Faulkner to Morrison By Kelly Lynch Reames Arab American Literary Fictions, Cultures, and Politics Steven Salaita ARAB AMERICAN LITERARY FICTIONS, CULTURES, AND POLITICS © Steven Salaita, 2007. Softcover reprint of the hardcover 1st edition 2007 978-1-4039-7620-8 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. First published in 2007 by PALGRAVE MACMILLAN™ 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10010 and Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire, England RG21 6XS Companies and representatives throughout the world. PALGRAVE MACMILLAN is the global academic imprint of the Palgrave Macmillan division of St. Martin’s Press, LLC and of Palgrave Macmillan Ltd. Macmillan® is a registered trademark in the United States, United Kingdom and other countries. Palgrave is a registered trademark in the European Union and other countries. ISBN 978-1-349-53687-0 ISBN 978-0-230-60337-0 (eBook) DOI 10.1057/9780230603370 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available from the Library of Congress. -

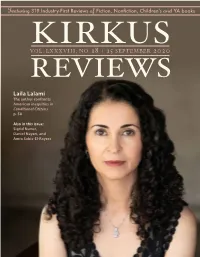

Kirkus Reviews on Our Website by Logging in As a Subscriber

Featuring 319 Industry-First Reviews of Fiction, Nonfiction, Children'sand YA books VOL.KIRKUS LXXXVIII, NO. 18 | 15 SEPTEMBER 2020 REVIEWS Laila Lalami The author confronts American inequities in Conditional Citizens p. 58 Also in this issue: Sigrid Nunez, Daniel Nayeri, and Amra Sabic-El-Rayess from the editor’s desk: The Way I Read Now Chairman BY TOM BEER HERBERT SIMON President & Publisher MARC WINKELMAN John Paraskevas # Among the many changes in my daily life this year—working from home, Chief Executive Officer wearing a mask in public, watching too much TV—my changing read- MEG LABORDE KUEHN ing habits register deeply. For one thing, I read on a Kindle now, with the [email protected] Editor-in-Chief exception of the rare galley sent to me at home and the books I’ve made TOM BEER a point of purchasing from local independent bookstores or ordering on [email protected] Vice President of Marketing Bookshop.org. The Kindle was borrowed—OK, confiscated—from my SARAH KALINA boyfriend at the beginning of the pandemic, when I left dozens of advance [email protected] reader copies behind at the office and accepted the reality that digital gal- Managing/Nonfiction Editor ERIC LIEBETRAU leys would be a practical necessity for the foreseeable future. I can’t say that I [email protected] love reading on my “new” Kindle—I’m still a sucker for physical books after Fiction Editor LAURIE MUCHNICK all these years—but I’ll admit that it fulfills its purpose efficiently. And I do [email protected] Tom Beer rather enjoy the instant gratification of going on NetGalley or Edelweiss Young Readers’ Editor VICKY SMITH and dispatching multiple books to my device in one fell swoop—a harmless [email protected] form of bingeing that affords a little dopamine rush. -

Moroccan Women and Immigration in Spanish Narrative and Film (1995-2008)

University of Kentucky UKnowledge University of Kentucky Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2010 MOROCCAN WOMEN AND IMMIGRATION IN SPANISH NARRATIVE AND FILM (1995-2008) Sandra Stickle Martín University of Kentucky, [email protected] Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Martín, Sandra Stickle, "MOROCCAN WOMEN AND IMMIGRATION IN SPANISH NARRATIVE AND FILM (1995-2008)" (2010). University of Kentucky Doctoral Dissertations. 766. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/gradschool_diss/766 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Kentucky Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION Sandra Stickle Martín The Graduate School University of Kentucky 2010 MOROCCAN WOMEN AND IMMIGRATION IN SPANISH NARRATIVE AND FILM (1995-2008) ___________________________________ ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION ____________________________________ A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of doctor of Philosophy in the College of Arts and Sciences at the University of Kentucky By Sandra Stickle Martín Lexington, Kentucky Director: Dr. Ana Rueda, Professor of Hispanic Studies Lexington, Kentucky 2010 Copyright © Sandra Stickle Martín 2010 ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION MOROCCAN WOMEN AND IMMIGRATION IN SPANISH NARRATIVE AND FILM (1995-2008) Spanish migration narratives and films present a series of conflicting forces: the assumptions of entitlement of both Western and Oriental patriarchal authority, the claims to autonomy and self determination by guardians of women’s rights, the confrontations between advocates of exclusion and hospitality in the host society, and the endeavor of immigrant communities to maintain traditions while they integrate into Spanish society. -

L'écriture De L'enfance Dans Le Texte Autobiographique Marocain

L’ÉCRITURE DE L’ENFANCE DANS LE TEXTE AUTOBIOGRAPHIQUE MAROCAIN. ÉLÉMENTS D’ANALYSE A TRAVERS L’ÉTUDE DE CINQ RÉCITS. LE CAS DE CHRAIBI, KHATIBI, CHOUKRI, MERNISSI ET RACHID O. By MUSTAPHA SAMI A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2013 1 © 2013 Sami Mustapha 2 To my family 3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I gratefully acknowledge my obligation to all the people who supported me during my work on this study. Especially I would first like to extend my sincere thanks to Dr. Alioune Sow, my Dissertation Director, for his strong support, continuous and invaluable input, and his patience and advice throughout the dissertation writing. My sincere gratitude and admiration to the other professors, members of my dissertation committee: Dr. William Calin, Dr. Brigitte Weltman and Dr. Fiona McLaughlin for their helpful comments and ongoing support. I would also like to thank all my professors at the University of Florida. 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................................... 4 LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS ............................................................................................. 7 ABSTRACT ..................................................................................................................... 8 CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION GÉNÉRALE ................................................................................ 10 1.1 -

The Role of Academia in Promoting Gender and Women’S Rights in the Arab World and the European Region

THE ROLE OF ACADEMIA IN PROMOTING GENDER AND WOMEN’S RIGHTS IN THE ARAB WORLD AND THE EUROPEAN REGION Erasmus+ project “Gender Studies Curriculum: A Step for Democracy and Peace in EU- Neighboring Countries with Different Traditions”, No. 561785-EPP-1-2015-1-LT-EPPKA2-CBHE-JP UDC 305(063) Dépôt Légal : 2019MO2902 ISBN : 978-9954-692-05-9 The Role Of Academia In Promoting Gender And Women’s Rights In The Arab World And The European Region // Edited by Souad Slaoui, Khalid Bekkaoui, Kebir Sandy, Sadik Rddad, Karima Belghiti. – Publ. Société Généraled’Equipement&d’impression, Fes, Morocco, 2019. – 382 pp. This book contains articles by participants in the Forum " The role of academia in promoting gender and women’s rights in the Arab world and the European region " (Morocco, Fez, October, 1- 5, 2018 ). In the articles, the actual problems of gender identity, gender equality, gender education, gender and politics, gender and religion are raised. The materials will be useful to researchers, scientists, graduate students and students dealing with the problems of gender equality, intersexual relations, statistical indices of gender equality and other aspects of this field. Technical Editors: Natalija Mažeikienė, Olga Avramenko, Volodymyr Naradovyi. Acknowedgements to PhD students Mrs.Hajar Brgharbi, Mr.Mouhssine El Hajjami who have extensively worked with editors on collecting the abstract and the paper at the first stage of the compilation of this Conference volume. Recommended for publication: Moroccan Cultural Studies Centre, University SIdi Mohammed Ben Abdallah, Faculty of Letters and Human Sciences Dhar Al Mahraz, Fez. ERASMUS+ Project “Gender Studies Curriculum: A Step for Democracy and Peace in EU- neighboring countries with different traditions – GeSt” [Ref. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Reimagining

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Reimagining Transatlantic Iberian Conquests in Postcolonial Narratives and Rewriting Spaces of Resistance A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Spanish by Seher Rabia Rowther March 2020 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Benjamin Liu, Chairperson Dr. Covadonga Lamar-Prieto Dr. Freya Schiwy Copyright by Seher Rabia Rowther 2020 The Dissertation of Seher Rabia Rowther is approved: Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside DEDICATION The best stories unite us despite our various disparities and experiences in life. The worst event I experienced in graduate school was the hospitalization of my mother and my grandmother in the winter of 2016. It was the most challenging period in my life because my parents have given me a beautiful life of love, laughter, protection, and guidance. My family has been the best living example of strength and compassion. The summer after my grandmother passed, I went to Spain for the first time in my life. While traveling through Spain, I saw her in a dream. She was smiling as she passed me by—the same way she used to walk through our house with her walker. When I left Spain to return home, I started reading Radwa Ashour’s trilogy on the plane. When Radwa wrote about the families of Granada historically removed from their homes and forced to trek across the kingdoms of Castile, she did not just describe the multitude and their possessions in tow. She wrote about a grandson carrying his grandmother until her last breath and then having to bury her in a place he did not even recognize. -

Cabeza De Vaca, Estebanico, and the Language of Diversity in Laila Lalami's the Moor's Account

Text Matters: A Journal of Literature, Theory and Culture Number 8 Engaging Ireland / American & Article 19 Canadian Studies October 2018 Cabeza de Vaca, Estebanico, and the Language of Diversity in Laila Lalami’s The Moor’s Account Zbigniew Maszewski University of Łódź Follow this and additional works at: https://digijournals.uni.lodz.pl/textmatters Recommended Citation Maszewski, Zbigniew. "Cabeza de Vaca, Estebanico, and the Language of Diversity in Laila Lalami’s The Moor’s Account." Text Matters: A Journal of Literature, Theory and Culture, no.8, 2020, pp. 320-331, doi:10.1515/texmat-2018-0019 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Arts & Humanities Journals at University of Lodz Research Online. It has been accepted for inclusion in Text Matters: A Journal of Literature, Theory and Culture by an authorized editor of University of Lodz Research Online. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Text Matters, Number 8, 2018 DOI: 10.1515/texmat-2018-0019 Zbigniew Maszewski University of Łódź Cabeza de Vaca, Estebanico, and the Language of Diversity in Laila Lalami’s The Moor’s Account A BSTR A CT Published in 1542, Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca’s La relación is a chronicle of the Pánfilo de Narváez’s 1527 expedition to the New World in which Cabeza de Vaca was one of the four survivors. His account has received considerable attention. It has been appreciated and critically examined as a narrative of conquest and colonization, a work of ethnographic interest, and a text of some literary value. -

Re-Writing Women's Identities and Experiences in Contemporary

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Research Repository Veiled experiences: re-writing women's identities and experiences in contemporary Muslim fiction in English Firouzeh Ameri B.A. Shahid Beheshti University, Tehran M.A. University of Tehran, Tehran This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of Murdoch University. 2012 i I declare that this thesis is my own account of my research and contains as its main content work which has not previously been submitted for a degree at any tertiary education institution. ii Abstract In dominant contemporary Western representations, including various media texts, popular fiction and life-narratives, both the Islamic faith in general and Muslim women in particular are often vilified and stereotyped. In many such representations Islam is introduced as a backward and violent religion, and Muslim women are represented as either its victims or its fortunate survivors. This trend in the representations of Islam and Muslim women has been markedly intensified following the terrorist attacks of 9/11 2001. This thesis takes a postpositivist realist approach to reading selected contemporary women’s fiction, written in English, and foregrounding the lives and religious identities of Muslim women who are neither victims nor escapees of Islam but willingly committed to their faith. Texts include The Translator (1999) and Minaret (2005) by Leila Aboulela, Does my head look big in this? (2005) by Randa Abdel-Fattah, Sweetness in the belly (2005) by Camilla Gibb and The girl in the tangerine scarf (2006) by Mohja Kahf. -

VF Pdf 10.36

1 « Le capital immatériel s’affirme désormais comme un des paramètres les plus récents qui ont été retenus au niveau international pour mesurer la valeur globale des Etats et des entreprises ». Extrait du Discours Royal à la Nation adressé à l’occasion de la Fête du Trône le 30 juillet 2014 PREFACE Longtemps, l’aspiration à l’universalité fut liée à une domination de fait, par la force ou l’idéologie, par la culture ou la religion, les technologies maîtri- sées ou l’élan conquérant d’une civilisation... Encore qualifiait-on d’universel ce qui régentait l’espace considéré comme le centre du monde du moment, ce que la vision d’aujourd’hui, notamment avec l’essor de la Chine et l’émer- gence de l’Afrique, relativise. Pour nous méditerranéens, l’universel fut entre autres et tour à tour grec, romain, arabe, italien avec la renaissance, etc. Au siècle «des Lumières» apparaît un concept nouveau, un universalisme phi- losophique construit sur le dialogue, l’écrit et le verbe, et fondé sur la raison comme seul ciment du consentement espéré de tous. D’autres prétentions à l’universel qui s’ensuivirent eurent moins de délicatesse ; l’humanité ne s’en est séparée qu’au prix de millions de morts. Mais des volontés autoritaires à vocation hégémoniste sont toujours là, des idéologies, des radicalismes religieux, des systèmes économiques domina- teurs, des modèles technologiques ou économiques voulus sans alternative, des impérialismes déguisés en évidences incontournables parfois. Ce sont des machines à laminer les libertés comme les identités. Ces candidats à l’universalisme ne font pas bon ménage avec les particula- rismes. -

Anthologie Des Écrivains Marocains De L'émigration

Anthologie des écrivains marocains de l’émigration © A. Retnani - La Croisée des Chemins Rue Essanaani, quartier bourgogne, 20050 Casablanca - Maroc [email protected] [email protected] Site Web : www.editionslacroiseedeschemins.com ISBN : 978-9954-1-0298-5 Dépôt légal : 2010 MO 0386 Salim Jay Anthologie des écrivains marocains de l’émigration Du même auteur - Brèves notes cliniques sur le cas Guy des Cars, Barbare, 1979 - La Semaine où Madame Simone eut cents ans, La Différence, 1979 - Le Fou de lecture et les quarante romans, Confrontation, 1981 - Tu seras Nabab, mon fils (sous le pseudonyme d’Irène Refrain), Rupture 1982 - Bernard Frank, Rupture 1982 - Romans maghrébins, l’Afrique littéraire, 1983 - Romans du monde noir, l’Afrique littéraire, 1984 - Portrait du géniteur en poète officiel,Denoël , 1985, réédition La Différence, 2008 - Idriss, Michel Tournier, et les autres, La Différence, 1986 - Cent un Maliens nous manquent, Arcantère, 1987 - L’Afrique de l’Occident (1887-1987), l’Afrique littéraire, 1987 - L’Oiseau vit de sa plume, Belfond, 1989 - Avez-vous lu Henri Thomas ?, Le Félin, 1990 - Les Écrivains sont dans leur assiette, « Point Virgule », Seuil, 1991 - Starlette au haras (sous le pseudonyme d’Alexandra Quadripley), Éditions de Septembre, 1992 - Du côté de Saint-Germain-des-Prés, Jacques Bertoin, 1992 - Pour Angelo Rinaldi, Belles Lettres, 1994 - Jean Freustié, romancier de la sincérité, Le Rocher, 1998 - Sagesse du milieu du monde, Paris Méditerranée, 1999 - Tu ne traverseras pas le détroit, -

The Story of How Estebanico Became Mustafa in Laila Lalami's The

– Centre for Languages and Literature English Studies The Story of How Estebanico Became Mustafa in Laila Lalami’s The Moor’s Account: Retelling Stories in a Post-Colonial Light Linnéa Ungewitter ENGK01 Degree project in English Literature Spring 2016 Centre for Languages and Literature Lund University Supervisor: Kiki Lindell Abstract Both post-colonialism and historical novels are highly topical research themes in today’s literary field, but storytelling as a genre has lost its status. This essay aims to look at the importance of storytelling in the 2014 published novel The Moor’s Account, and how storytelling can be connected to post-colonial rewritings of history. This is achieved through looking at the emphasis on storytelling in the novel, and then drawing connections between retelling stories and rewriting history. Finally this is situated in a post-colonial discourse and analysis. This essay concludes that author Laila Lalami successfully integrates a Moroccan literary tradition of storytelling with a rewriting of a Western travelogue, while also using the act of telling stories to give a voice and identity to a silenced historical person. Lalami’s novel also shows how the multi-voiced aspect of retelling stories promotes diversity, and that the far from primitive genre of storytelling has a given place in literature generally, and in post-colonial novels especially. Keywords: storytelling, post-colonialism, plurality, diversity, New Historicism, identity, history, rewritings, hybridity, Morocco, Cabeza de Vaca, Laila Lalami Table of Contents Introduction 1 Telling a Story – Forming an Identity 2 Retelling a Story – New Historicism and Historical Fiction 8 A Story About Post-colonialism 12 Conclusion 18 Works Cited 20 Introduction The world is filled with stories: stories about a long lost past, stories about people, stories about events and even stories about yourself and people around you.