Download Book

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Laila Lalami: Narrating North African Migration to Europe

Laila Lalami: Narrating North African Migration to Europe CHRISTIÁN H. RICCI UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, MERCED Introduction aila Lalami, author of three novels—Hope and Other Dangerous Pursuits L(2005), Secret Son (2009), and The Moor’s Account (2014)—and several short stories, has been considered the most important Moroccan author writ- ing in English; her work has been translated into more than eleven languages (Mehta 117). Compelled to write in a language that is not her mother tongue, Lalami’s narrations constitute a form of diasporic writing from within. She succeeds in defying not only the visual and cultural vilification of Muslims, but also the prevailing neo-orientalist concept of Muslim women’s writing as exclusively victim or escapee narratives. Up to now, the focus of most Mo- roccan migration stories “has been on male migrants as individuals, without reference to women, who nowadays constitute about 50% of international migration. This has led to the neglect of women in migration theories” (Ennaji and Sadiqui 8, 14). As the result of labor migration and family reunification (twenty percent of Moroccan citizens now live in Europe), combined with the geo- graphic proximity of Europe and North Africa, the notion of a national or “native” literature is slightly unstable with regard to Morocco. Its literary production is not limited by the borders of the nation-state, but spills over to the European continent, where the largest Moroccan-descent communities are in France (over a million), Spain (800,000), the Netherlands (370,000), and Belgium (200,000). Contemporary Moroccan literature does more than criticize and reb- el against the Makhzen, a term that originally refers to the storehouse where tribute and taxes to the sultan were stowed; through the centuries Makhzen has come to signify not just the power holders in Morocco, but how power has been exercised throughout society. -

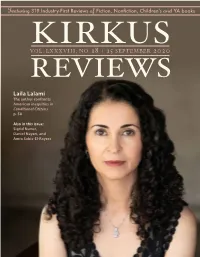

Kirkus Reviews on Our Website by Logging in As a Subscriber

Featuring 319 Industry-First Reviews of Fiction, Nonfiction, Children'sand YA books VOL.KIRKUS LXXXVIII, NO. 18 | 15 SEPTEMBER 2020 REVIEWS Laila Lalami The author confronts American inequities in Conditional Citizens p. 58 Also in this issue: Sigrid Nunez, Daniel Nayeri, and Amra Sabic-El-Rayess from the editor’s desk: The Way I Read Now Chairman BY TOM BEER HERBERT SIMON President & Publisher MARC WINKELMAN John Paraskevas # Among the many changes in my daily life this year—working from home, Chief Executive Officer wearing a mask in public, watching too much TV—my changing read- MEG LABORDE KUEHN ing habits register deeply. For one thing, I read on a Kindle now, with the [email protected] Editor-in-Chief exception of the rare galley sent to me at home and the books I’ve made TOM BEER a point of purchasing from local independent bookstores or ordering on [email protected] Vice President of Marketing Bookshop.org. The Kindle was borrowed—OK, confiscated—from my SARAH KALINA boyfriend at the beginning of the pandemic, when I left dozens of advance [email protected] reader copies behind at the office and accepted the reality that digital gal- Managing/Nonfiction Editor ERIC LIEBETRAU leys would be a practical necessity for the foreseeable future. I can’t say that I [email protected] love reading on my “new” Kindle—I’m still a sucker for physical books after Fiction Editor LAURIE MUCHNICK all these years—but I’ll admit that it fulfills its purpose efficiently. And I do [email protected] Tom Beer rather enjoy the instant gratification of going on NetGalley or Edelweiss Young Readers’ Editor VICKY SMITH and dispatching multiple books to my device in one fell swoop—a harmless [email protected] form of bingeing that affords a little dopamine rush. -

Moroccan Women and Immigration in Spanish Narrative and Film (1995-2008)

University of Kentucky UKnowledge University of Kentucky Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2010 MOROCCAN WOMEN AND IMMIGRATION IN SPANISH NARRATIVE AND FILM (1995-2008) Sandra Stickle Martín University of Kentucky, [email protected] Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Martín, Sandra Stickle, "MOROCCAN WOMEN AND IMMIGRATION IN SPANISH NARRATIVE AND FILM (1995-2008)" (2010). University of Kentucky Doctoral Dissertations. 766. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/gradschool_diss/766 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Kentucky Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION Sandra Stickle Martín The Graduate School University of Kentucky 2010 MOROCCAN WOMEN AND IMMIGRATION IN SPANISH NARRATIVE AND FILM (1995-2008) ___________________________________ ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION ____________________________________ A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of doctor of Philosophy in the College of Arts and Sciences at the University of Kentucky By Sandra Stickle Martín Lexington, Kentucky Director: Dr. Ana Rueda, Professor of Hispanic Studies Lexington, Kentucky 2010 Copyright © Sandra Stickle Martín 2010 ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION MOROCCAN WOMEN AND IMMIGRATION IN SPANISH NARRATIVE AND FILM (1995-2008) Spanish migration narratives and films present a series of conflicting forces: the assumptions of entitlement of both Western and Oriental patriarchal authority, the claims to autonomy and self determination by guardians of women’s rights, the confrontations between advocates of exclusion and hospitality in the host society, and the endeavor of immigrant communities to maintain traditions while they integrate into Spanish society. -

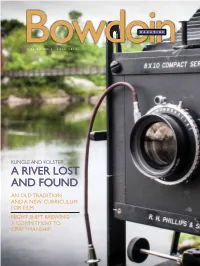

2012-Fall.Pdf

MAGAZINE BowdoiVOL.84 NO.1 FALL 2012 n KLINGLE AND KOLSTER A RIVER LOST AND FOUND AN OLD TRADITION AND A NEW CURRICULUM FOR FILM NIGHT SHIFT BREWING: A COMMITMENT TO CRAFTMANSHIP FALL 2012 BowdoinMAGAZINE CONTENTS 14 A River Lost and Found BY EDGAR ALLEN BEEM PHOTOGRAPHS BY BRIAN WEDGE ’97 AND MIKE KOLSTER Ed Beem talks to Professors Klingle and Kolster about their collaborative multimedia project telling the story of the Androscoggin River through photographs, oral histories, archival research, video, and creative writing. 24 Speaking the Language of Film "9,)3!7%3%,s0(/4/'2!0(3"9-)#(%,%34!0,%4/. An old tradition and a new curriculum combine to create an environment for film studies to flourish at Bowdoin. 32 Working the Night Shift "9)!.!,$2)#(s0(/4/'2!0(3"90!40)!3%#+) After careful research, many a long night brewing batches of beer, and with a last leap of faith, Rob Burns ’07, Michael Oxton ’07, and their business partner Mike O’Mara, have themselves a brewery. DEPARTMENTS Bookshelf 3 Class News 41 Mailbox 6 Weddings 78 Bowdoinsider 10 Obituaries 91 Alumnotes 40 Whispering Pines 124 [email protected] 1 |letter| Bowdoin FROM THE EDITOR MAGAZINE Happy Accidents Volume 84, Number 1 I live in Topsham, on the bank of the Androscoggin River. Our property is a Fall 2012 long and narrow lot that stretches from the road down the hill to our house, MAGAZINE STAFF then further down the hill, through a low area that often floods when the tide is Editor high, all the way to the water. -

The Role of Academia in Promoting Gender and Women’S Rights in the Arab World and the European Region

THE ROLE OF ACADEMIA IN PROMOTING GENDER AND WOMEN’S RIGHTS IN THE ARAB WORLD AND THE EUROPEAN REGION Erasmus+ project “Gender Studies Curriculum: A Step for Democracy and Peace in EU- Neighboring Countries with Different Traditions”, No. 561785-EPP-1-2015-1-LT-EPPKA2-CBHE-JP UDC 305(063) Dépôt Légal : 2019MO2902 ISBN : 978-9954-692-05-9 The Role Of Academia In Promoting Gender And Women’s Rights In The Arab World And The European Region // Edited by Souad Slaoui, Khalid Bekkaoui, Kebir Sandy, Sadik Rddad, Karima Belghiti. – Publ. Société Généraled’Equipement&d’impression, Fes, Morocco, 2019. – 382 pp. This book contains articles by participants in the Forum " The role of academia in promoting gender and women’s rights in the Arab world and the European region " (Morocco, Fez, October, 1- 5, 2018 ). In the articles, the actual problems of gender identity, gender equality, gender education, gender and politics, gender and religion are raised. The materials will be useful to researchers, scientists, graduate students and students dealing with the problems of gender equality, intersexual relations, statistical indices of gender equality and other aspects of this field. Technical Editors: Natalija Mažeikienė, Olga Avramenko, Volodymyr Naradovyi. Acknowedgements to PhD students Mrs.Hajar Brgharbi, Mr.Mouhssine El Hajjami who have extensively worked with editors on collecting the abstract and the paper at the first stage of the compilation of this Conference volume. Recommended for publication: Moroccan Cultural Studies Centre, University SIdi Mohammed Ben Abdallah, Faculty of Letters and Human Sciences Dhar Al Mahraz, Fez. ERASMUS+ Project “Gender Studies Curriculum: A Step for Democracy and Peace in EU- neighboring countries with different traditions – GeSt” [Ref. -

American Book Awards 2004

BEFORE COLUMBUS FOUNDATION PRESENTS THE AMERICAN BOOK AWARDS 2004 America was intended to be a place where freedom from discrimination was the means by which equality was achieved. Today, American culture THE is the most diverse ever on the face of this earth. Recognizing literary excel- lence demands a panoramic perspective. A narrow view strictly to the mainstream ignores all the tributaries that feed it. American literature is AMERICAN not one tradition but all traditions. From those who have been here for thousands of years to the most recent immigrants, we are all contributing to American culture. We are all being translated into a new language. BOOK Everyone should know by now that Columbus did not “discover” America. Rather, we are all still discovering America—and we must continue to do AWARDS so. The Before Columbus Foundation was founded in 1976 as a nonprofit educational and service organization dedicated to the promotion and dissemination of contemporary American multicultural literature. The goals of BCF are to provide recognition and a wider audience for the wealth of cultural and ethnic diversity that constitutes American writing. BCF has always employed the term “multicultural” not as a description of an aspect of American literature, but as a definition of all American litera- ture. BCF believes that the ingredients of America’s so-called “melting pot” are not only distinct, but integral to the unique constitution of American Culture—the whole comprises the parts. In 1978, the Board of Directors of BCF (authors, editors, and publishers representing the multicultural diversity of American Literature) decided that one of its programs should be a book award that would, for the first time, respect and honor excellence in American literature without restric- tion or bias with regard to race, sex, creed, cultural origin, size of press or ad budget, or even genre. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Reimagining

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Reimagining Transatlantic Iberian Conquests in Postcolonial Narratives and Rewriting Spaces of Resistance A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Spanish by Seher Rabia Rowther March 2020 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Benjamin Liu, Chairperson Dr. Covadonga Lamar-Prieto Dr. Freya Schiwy Copyright by Seher Rabia Rowther 2020 The Dissertation of Seher Rabia Rowther is approved: Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside DEDICATION The best stories unite us despite our various disparities and experiences in life. The worst event I experienced in graduate school was the hospitalization of my mother and my grandmother in the winter of 2016. It was the most challenging period in my life because my parents have given me a beautiful life of love, laughter, protection, and guidance. My family has been the best living example of strength and compassion. The summer after my grandmother passed, I went to Spain for the first time in my life. While traveling through Spain, I saw her in a dream. She was smiling as she passed me by—the same way she used to walk through our house with her walker. When I left Spain to return home, I started reading Radwa Ashour’s trilogy on the plane. When Radwa wrote about the families of Granada historically removed from their homes and forced to trek across the kingdoms of Castile, she did not just describe the multitude and their possessions in tow. She wrote about a grandson carrying his grandmother until her last breath and then having to bury her in a place he did not even recognize. -

The Poetry Project Newsletter

THE POETRY PROJECT NEWSLETTER $5.00 #212 OCTOBER/NOVEMBER 2007 How to Be Perfect POEMS BY RON PADGETT ISBN: 978-1-56689-203-2 “Ron Padgett’s How to Be Perfect is. New Perfect.” —lyn hejinian Poetry Ripple Effect: from New and Selected Poems BY ELAINE EQUI ISBN: 978-1-56689-197-4 Coffee “[Equi’s] poems encourage readers House to see anew.” —New York Times The Marvelous Press Bones of Time: Excavations and Explanations POEMS BY BRENDA COULTAS ISBN: 978-1-56689-204-9 “This is a revelatory book.” —edward sanders COMING SOON Vertigo Poetry from POEMS BY MARTHA RONK Anne Boyer, ISBN: 978-1-56689-205-6 Linda Hogan, “Short, stunning lyrics.” —Publishers Weekly Eugen Jebeleanu, (starred review) Raymond McDaniel, A.B. Spellman, and Broken World Marjorie Welish. POEMS BY JOSEPH LEASE ISBN: 978-1-56689-198-1 “An exquisite collection!” —marjorie perloff Skirt Full of Black POEMS BY SUN YUNG SHIN ISBN: 978-1-56689-199-8 “A spirited and restless imagination at work.” Good books are brewing at —marilyn chin www.coffeehousepress.org THE POETRY PROJECT ST. MARK’S CHURCH in-the-BowerY 131 EAST 10TH STREET NEW YORK NY 10003 NEWSLETTER www.poetryproject.com #212 OCTOBER/NOVEMBER 2007 NEWSLETTER EDITOR John Coletti WELCOME BACK... DISTRIBUTION Small Press Distribution, 1341 Seventh St., Berkeley, CA 94710 4 ANNOUNCEMENTS THE POETRY PROJECT LTD. STAFF ARTISTIC DIRECTOR Stacy Szymaszek PROGRAM COORDINATOR Corrine Fitzpatrick PROGRAM ASSISTANT Arlo Quint 6 WRITING WORKSHOPS MONDAY NIGHT COORDINATOR Akilah Oliver WEDNESDAY NIGHT COORDINATOR Stacy Szymaszek FRIDAY NIGHT COORDINATOR Corrine Fitzpatrick 7 REMEMBERING SEKOU SUNDIATA SOUND TECHNICIAN David Vogen BOOKKEEPER Stephen Rosenthal DEVELOpmENT CONSULTANT Stephanie Gray BOX OFFICE Courtney Frederick, Erika Recordon, Nicole Wallace 8 IN CONVERSATION INTERNS Diana Hamilton, Owen Hutchinson, Austin LaGrone, Nicole Wallace A CHAT BETWEEN BRENDA COULTAS AND AKILAH OLIVER VOLUNTEERS Jim Behrle, David Cameron, Christine Gans, HR Hegnauer, Sarah Kolbasowski, Dgls. -

1 Preliminary Material

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Brownness: Mixed Identifications in Minority Immigrant Literature, 1900-1960 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1h43b9hg Author Rana, Swati Publication Date 2012 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Brownness: Mixed Identifications in Minority Immigrant Literature, 1900-1960 by Swati Rana A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Colleen Lye, Chair Professor Gautam Premnath Professor Marcial González Professor Rebecca McLennan Spring 2012 Copyright © 2012 by Swati Rana Abstract Brownness: Mixed Identifications in Minority Immigrant Literature, 1900-1960 by Swati Rana Doctor of Philosophy in English University of California, Berkeley Professor Colleen Lye, Chair My dissertation challenges our preconceptions of the ethnic literary tradition in the United States. Minority literature is generally read within a framework of resistance that prioritizes anti-hegemonic and anti-racist writings. I focus on a set of recalcitrant texts, written in the first part of the twentieth century, that do not fit neatly within this framework. My chapters trace an arc from Ameen Rihani’s !e Book of Khalid (1911), which personifies a universal citizen who refuses to be either Arab or American, to Paule Marshall’s Brown Girl, Brownstones (1959), which dramatizes the appeal of white identification for upwardly mobile Barbadian immigrants. I present the first comparative analysis of Afro-Caribbean, Arab, Filipino, Latino, and South Asian immigrant writings. !is archive includes familiar figures such as Claude McKay and William Carlos Williams as well as understudied writers such as Abraham Rihbany and Dalip Singh Saund. -

The Reconfiguration of Gender Relations in Syrian-American

Clio Women, Gender, History 37 | 2013 When Medicine Meets Gender The reconfiguration of gender relations in Syrian- American feminist discourse in the diasporic conditions of the late nineteenth century Dominique Cadinot Translator: Jeffrey Burkholder Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/cliowgh/413 DOI: 10.4000/cliowgh.413 ISSN: 2554-3822 Publisher Belin Electronic reference Dominique Cadinot, « The reconfiguration of gender relations in Syrian-American feminist discourse in the diasporic conditions of the late nineteenth century », Clio [Online], 37 | 2013, Online since 15 April 2014, connection on 01 May 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/cliowgh/413 ; DOI : 10.4000/ cliowgh.413 Clio The reconfiguration of gender relations and Syrian- American feminist discourse in the transnational space of the latter nineteenth century Dominique CADINOT The prejudices concerning Arab-Muslim civilization that have become so ingrained in popular imagination began to be perpetuated in the United States at the end of the Barbary Wars, fought by the Americans against the Ottoman regencies of North Africa between 1801 and 1815. This first US victory over the Arab world was perceived by Americans as a sign from Providence, confirming the superiority of their values and ideals over those of their adversaries. It is from this era that the image of the Arab woman begins to be associated with that of the odalisque of the harem, a sexual object, or with that of the ignorant wife reduced to servitude under her veil.1 However, in the United States of the early 20th century, immigrant women from the Middle East took advantage of their exile and their contact with American society to start breaking away from traditional social practices, thus demonstrating their will to free themselves from these gender stereotypes. -

5.00 #216 October/November 2008

$5.00 #216 OCTOBER/NOVEMBER 2008 New Books from Hanging Loose Press Tony Towle Sharon Mesmer Michael Cirelli William Corbett Winter Journey The Virgin Formica Lobster with Ol’ Opening Day Raves from his last “At turns intimate or Dirty Bastard A large new collection collection: Tony Towle boisterously satiric, “Vital and eye- of poems. Of past is “one of the New York The Virgin Formica catching and new.” – books: “Taut, School’s best-kept can gently detonate or David Lehman. precise...lucid and secrets.” – John erupt, carrying “Shows how hip-hop unflinching...” – Siri Ashbery. “Tony Towle’s readers along on is the evolution of Hustvedt. “One of the is one of the clear, ripples or classic poetry.” – few poets of our time authentic voices of shockwaves.” – Paul Kanye West. “Tender, who attends so well to American poetry.” – Violi. tough, revelatory...a the ear.” – Library Kenneth Koch. “Smart Praise for previous voice that doesn’t Journal. “Corbett is and sly, sure to disarm work: “. beautifully seem to have occurred interested in the and delight.” – Billy bold and vivaciously before.” – Patricia moment of clarity – Collins. His twelfth modern.” – Allen Smith. First revelation – and lets collection. Ginsberg. collection, by the the force and nature Paper, $16. Hardcover, Paper, $16. director of Urban of ‘seeing’...generate $26. Hardcover, $26. Word NYC. shapes in language.” – August Kleinzahler. Indran Marie Carter Paper, $16. Hardcover, $26. Paper, $16. Amirthanayagam The Trapeze Hardcover, $26. The Splintered Diaries R. Zamora Face: Tsunami Linmark Poems First book from the And keep in mind – editor of Word Jig: New The Evolution of a “These poems both Fiction from Scotland. -

Poetry Journals and Chapbooks Collection MSS.2010.10.04

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt958038pg No online items Guide to the Poetry Journals and Chapbooks Collection MSS.2010.10.04 SJSU Special Collections & Archives © 2010 Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Library San José State University One Washington Square San José, CA 95192-0028 [email protected] URL: http://library.sjsu.edu/sjsu-special-collections/sjsu-special-collections-and-archives Guide to the Poetry Journals and MSS.2010.10.04 1 Chapbooks Collection MSS.2010.10.04 Language of Material: English Contributing Institution: SJSU Special Collections & Archives Title: Poetry Journals and Chapbooks Collection creator: San Jose Museum of Art Identifier/Call Number: MSS.2010.10.04 Physical Description: 7.0 boxes Date (inclusive): 1930-1984 Abstract: The Poetry Journals and Chapbooks Collection provides a representative sample of the poetry published in the United States during the 1970s and early 1980s. The collection includes poetry chapbooks and journal issues, literary catalogs, publishing guides, magazine and press directories, broadsides, art prints, and other items. Most of the poetry journals and chapbooks were produced by small presses in the United States. A few of the journals contain interviews with writers and poets and some contain articles of poetry criticism. The journal titles include Big Moon, Bug Tar, The Chowder Review, Green's Magazine, Kayak, Vagabond, Wind, and The Wormwood Review. This collection is arranged into two series: Series I. Poetry Journals and Chapbooks 1930-1984 (bulk 1972-1983), n.d.; Series II. Miscellaneous Poetry 1970-1984 (bulk 1973-1979), n.d. In addition, there are a few feature poems by Charles Bukowski located in Series II.