UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Reimagining

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Coronado and Aesop Fable and Violence on the Sixteenth-Century Plains

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Great Plains Quarterly Great Plains Studies, Center for 2009 Coronado and Aesop Fable and Violence on the Sixteenth-Century Plains Daryl W. Palmer Regis University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly Part of the Other International and Area Studies Commons Palmer, Daryl W., "Coronado and Aesop Fable and Violence on the Sixteenth-Century Plains" (2009). Great Plains Quarterly. 1203. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly/1203 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Great Plains Studies, Center for at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Great Plains Quarterly by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. CORONADO AND AESOP FABLE AND VIOLENCE ON THE SIXTEENTH~CENTURY PLAINS DARYL W. PALMER In the spring of 1540, Francisco Vazquez de the killing of this guide for granted, the vio Coronado led an entrada from present-day lence was far from straightforward. Indeed, Mexico into the region we call New Mexico, the expeditionaries' actions were embedded where the expedition spent a violent winter in sixteenth-century Spanish culture, a milieu among pueblo peoples. The following year, that can still reward study by historians of the after a long march across the Great Plains, Great Plains. Working within this context, I Coronado led an elite group of his men north explore the ways in which Aesop, the classical into present-day Kansas where, among other master of the fable, may have informed the activities, they strangled their principal Indian Spaniards' actions on the Kansas plains. -

Laila Lalami: Narrating North African Migration to Europe

Laila Lalami: Narrating North African Migration to Europe CHRISTIÁN H. RICCI UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, MERCED Introduction aila Lalami, author of three novels—Hope and Other Dangerous Pursuits L(2005), Secret Son (2009), and The Moor’s Account (2014)—and several short stories, has been considered the most important Moroccan author writ- ing in English; her work has been translated into more than eleven languages (Mehta 117). Compelled to write in a language that is not her mother tongue, Lalami’s narrations constitute a form of diasporic writing from within. She succeeds in defying not only the visual and cultural vilification of Muslims, but also the prevailing neo-orientalist concept of Muslim women’s writing as exclusively victim or escapee narratives. Up to now, the focus of most Mo- roccan migration stories “has been on male migrants as individuals, without reference to women, who nowadays constitute about 50% of international migration. This has led to the neglect of women in migration theories” (Ennaji and Sadiqui 8, 14). As the result of labor migration and family reunification (twenty percent of Moroccan citizens now live in Europe), combined with the geo- graphic proximity of Europe and North Africa, the notion of a national or “native” literature is slightly unstable with regard to Morocco. Its literary production is not limited by the borders of the nation-state, but spills over to the European continent, where the largest Moroccan-descent communities are in France (over a million), Spain (800,000), the Netherlands (370,000), and Belgium (200,000). Contemporary Moroccan literature does more than criticize and reb- el against the Makhzen, a term that originally refers to the storehouse where tribute and taxes to the sultan were stowed; through the centuries Makhzen has come to signify not just the power holders in Morocco, but how power has been exercised throughout society. -

Reef-Coral Fauna of Carrizo Creek, Imperial County, California, and Its Significance

THE REEF-CORAL FAUNA OF CARRIZO CREEK, IMPERIAL COUNTY, CALIFORNIA, AND ITS SIGNIFICANCE . .By THOMAS WAYLAND VAUGHAN . INTRODUCTION. occur has been determined by Drs . Arnold and Dall to be lower Miocene . The following conclusions seem warranted : Knowledge of the existence of the unusually (1) There was water connection between the Atlantic and interesting coral fauna here discussed dates Pacific across Central America not much previous to the from the exploration of Coyote Mountain (also upper Oligocene or lower Miocene-that is, during the known as Carrizo Mountain) by H . W. Fair- upper Eocene or lower Oligocene . This conclusion is the same as that reached by Messrs. Hill and Dall, theirs, how- banks in the early nineties.' Dr. Fairbanks ever, being based upon a study of the fossil mollusks . (2) sent the specimens of corals he collected to During lower Miocene time the West Indian type of coral Prof. John C. Merriam, at the University of fauna extended westward into the Pacific, and it was sub- California, who in turn sent them to me . sequent to that time that the Pacific and Atlantic faunas There were in the collection representatives of have become so markedly differentiated . two species and one variety, which I described As it will be made evident on subsequent under the names Favia merriami, 2 Stephano- pages that this fauna is much younger than ctenia fairbanksi,3 and Stephanoccenia fair- lower Miocene, the inference as to the date of banksi var. columnaris .4 As the geologic hori- the interoceanic connection given in the fore- zon was not even approximately known at that going quotation must be modified . -

Alternative Names of a Maritime Feature: the Case of the Caribbean Sea

Alternative names of a maritime feature: The case of the Caribbean Sea POKOLY Béla* 1) The Caribbean Sea has been known by this name in the English language for several centuries. It is the widely accepted name in international contacts, and is so recorded by the International Hydrographic Organization. Still in some languages it is alternatively referred to as the Sea of the Antilles, especially in French. It may reflect the age of explorations, when the feature had various names. In Hungarian cartography it is one of the few marine features shown by giving the alter- native name in brackets: Karib (Antilla)‐ tenger (English Caribbean Sea /Sea of the Antilles/). 1. Introduction A look at any map or encyclopaedia would confirm that the Caribbean Sea is one of the major bodies of water of the world. With an approximate area of 2,750,000 km² (1,050,000 square miles), only the five oceans and the Mediterranean Sea are larger by surface. The sea is deepest at the Cayman Trough (or Cayman Trench) which has a maximum depth of 7,686 metres, where the North American and Caribbean plates create a complex zone of spreading and transform faults. The area witnessed two major seismic catastrophes in the past centuries: the 1692 Jamaica earthquake, and the 2010 Haiti earthquake. One associates the Caribbean, as a great sea with several features and facts. The three arguably most important facts coupled with the Caribbean: * Senior Advisor, Committee on Geographical Names, Ministry of Agriculture and Regional Development, Hungary 23 POKOLY Béla Exploration Columbus’ voyages of discovery to the bordering archipelago. -

Download Book

Arab American Literary Fictions, Cultures, and Politics American Literature Readings in the 21st Century Series Editor: Linda Wagner-Martin American Literature Readings in the 21st Century publishes works by contemporary critics that help shape critical opinion regarding literature of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries in the United States. Published by Palgrave Macmillan Freak Shows in Modern American Imagination: Constructing the Damaged Body from Willa Cather to Truman Capote By Thomas Fahy Arab American Literary Fictions, Cultures, and Politics By Steven Salaita Women and Race in Contemporary U.S. Writing: From Faulkner to Morrison By Kelly Lynch Reames Arab American Literary Fictions, Cultures, and Politics Steven Salaita ARAB AMERICAN LITERARY FICTIONS, CULTURES, AND POLITICS © Steven Salaita, 2007. Softcover reprint of the hardcover 1st edition 2007 978-1-4039-7620-8 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. First published in 2007 by PALGRAVE MACMILLAN™ 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10010 and Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire, England RG21 6XS Companies and representatives throughout the world. PALGRAVE MACMILLAN is the global academic imprint of the Palgrave Macmillan division of St. Martin’s Press, LLC and of Palgrave Macmillan Ltd. Macmillan® is a registered trademark in the United States, United Kingdom and other countries. Palgrave is a registered trademark in the European Union and other countries. ISBN 978-1-349-53687-0 ISBN 978-0-230-60337-0 (eBook) DOI 10.1057/9780230603370 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available from the Library of Congress. -

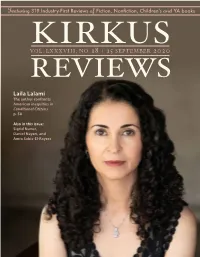

Kirkus Reviews on Our Website by Logging in As a Subscriber

Featuring 319 Industry-First Reviews of Fiction, Nonfiction, Children'sand YA books VOL.KIRKUS LXXXVIII, NO. 18 | 15 SEPTEMBER 2020 REVIEWS Laila Lalami The author confronts American inequities in Conditional Citizens p. 58 Also in this issue: Sigrid Nunez, Daniel Nayeri, and Amra Sabic-El-Rayess from the editor’s desk: The Way I Read Now Chairman BY TOM BEER HERBERT SIMON President & Publisher MARC WINKELMAN John Paraskevas # Among the many changes in my daily life this year—working from home, Chief Executive Officer wearing a mask in public, watching too much TV—my changing read- MEG LABORDE KUEHN ing habits register deeply. For one thing, I read on a Kindle now, with the [email protected] Editor-in-Chief exception of the rare galley sent to me at home and the books I’ve made TOM BEER a point of purchasing from local independent bookstores or ordering on [email protected] Vice President of Marketing Bookshop.org. The Kindle was borrowed—OK, confiscated—from my SARAH KALINA boyfriend at the beginning of the pandemic, when I left dozens of advance [email protected] reader copies behind at the office and accepted the reality that digital gal- Managing/Nonfiction Editor ERIC LIEBETRAU leys would be a practical necessity for the foreseeable future. I can’t say that I [email protected] love reading on my “new” Kindle—I’m still a sucker for physical books after Fiction Editor LAURIE MUCHNICK all these years—but I’ll admit that it fulfills its purpose efficiently. And I do [email protected] Tom Beer rather enjoy the instant gratification of going on NetGalley or Edelweiss Young Readers’ Editor VICKY SMITH and dispatching multiple books to my device in one fell swoop—a harmless [email protected] form of bingeing that affords a little dopamine rush. -

Moroccan Women and Immigration in Spanish Narrative and Film (1995-2008)

University of Kentucky UKnowledge University of Kentucky Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2010 MOROCCAN WOMEN AND IMMIGRATION IN SPANISH NARRATIVE AND FILM (1995-2008) Sandra Stickle Martín University of Kentucky, [email protected] Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Martín, Sandra Stickle, "MOROCCAN WOMEN AND IMMIGRATION IN SPANISH NARRATIVE AND FILM (1995-2008)" (2010). University of Kentucky Doctoral Dissertations. 766. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/gradschool_diss/766 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Kentucky Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION Sandra Stickle Martín The Graduate School University of Kentucky 2010 MOROCCAN WOMEN AND IMMIGRATION IN SPANISH NARRATIVE AND FILM (1995-2008) ___________________________________ ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION ____________________________________ A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of doctor of Philosophy in the College of Arts and Sciences at the University of Kentucky By Sandra Stickle Martín Lexington, Kentucky Director: Dr. Ana Rueda, Professor of Hispanic Studies Lexington, Kentucky 2010 Copyright © Sandra Stickle Martín 2010 ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION MOROCCAN WOMEN AND IMMIGRATION IN SPANISH NARRATIVE AND FILM (1995-2008) Spanish migration narratives and films present a series of conflicting forces: the assumptions of entitlement of both Western and Oriental patriarchal authority, the claims to autonomy and self determination by guardians of women’s rights, the confrontations between advocates of exclusion and hospitality in the host society, and the endeavor of immigrant communities to maintain traditions while they integrate into Spanish society. -

The Role of Academia in Promoting Gender and Women’S Rights in the Arab World and the European Region

THE ROLE OF ACADEMIA IN PROMOTING GENDER AND WOMEN’S RIGHTS IN THE ARAB WORLD AND THE EUROPEAN REGION Erasmus+ project “Gender Studies Curriculum: A Step for Democracy and Peace in EU- Neighboring Countries with Different Traditions”, No. 561785-EPP-1-2015-1-LT-EPPKA2-CBHE-JP UDC 305(063) Dépôt Légal : 2019MO2902 ISBN : 978-9954-692-05-9 The Role Of Academia In Promoting Gender And Women’s Rights In The Arab World And The European Region // Edited by Souad Slaoui, Khalid Bekkaoui, Kebir Sandy, Sadik Rddad, Karima Belghiti. – Publ. Société Généraled’Equipement&d’impression, Fes, Morocco, 2019. – 382 pp. This book contains articles by participants in the Forum " The role of academia in promoting gender and women’s rights in the Arab world and the European region " (Morocco, Fez, October, 1- 5, 2018 ). In the articles, the actual problems of gender identity, gender equality, gender education, gender and politics, gender and religion are raised. The materials will be useful to researchers, scientists, graduate students and students dealing with the problems of gender equality, intersexual relations, statistical indices of gender equality and other aspects of this field. Technical Editors: Natalija Mažeikienė, Olga Avramenko, Volodymyr Naradovyi. Acknowedgements to PhD students Mrs.Hajar Brgharbi, Mr.Mouhssine El Hajjami who have extensively worked with editors on collecting the abstract and the paper at the first stage of the compilation of this Conference volume. Recommended for publication: Moroccan Cultural Studies Centre, University SIdi Mohammed Ben Abdallah, Faculty of Letters and Human Sciences Dhar Al Mahraz, Fez. ERASMUS+ Project “Gender Studies Curriculum: A Step for Democracy and Peace in EU- neighboring countries with different traditions – GeSt” [Ref. -

Prince Henry the Navigator, Who Brought This Move Ment of European Expansion Within Sight of Its Greatest Successes

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. https://books.google.com PrinceHenrytheNavigator CharlesRaymondBeazley 1 - 1 1 J fteroes of tbe TRattong EDITED BY Sveltn Bbbott, flD.B. FELLOW OF BALLIOL COLLEGE, OXFORD PACTA DUOS VIVE NT, OPEROSAQUE OLMIA MHUM.— OVID, IN LI VI AM, f«». THE HERO'S DEEDS AND HARD-WON FAME SHALL LIVE. PRINCE HENRY THE NAVIGATOR GATEWAY AT BELEM. WITH STATUE, BETWEEN THE DOORS, OF PRINCE HENRY IN ARMOUR. Frontispiece. 1 1 l i "5 ' - "Hi:- li: ;, i'O * .1 ' II* FV -- .1/ i-.'..*. »' ... •S-v, r . • . '**wW' PRINCE HENRY THE NAVIGATOR THE HERO OF PORTUGAL AND OF MODERN DISCOVERY I 394-1460 A.D. WITH AN ACCOUNr Of" GEOGRAPHICAL PROGRESS THROUGH OUT THE MIDDLE AGLi> AS THE PREPARATION FOR KIS WORlf' BY C. RAYMOND BEAZLEY, M.A., F.R.G.S. FELLOW OF MERTON 1 fr" ' RifrB | <lvFnwn ; GEOGRAPHICAL STUDEN^rf^fHB-SrraSR^tttpXFORD, 1894 ule. Seneca, Medea P. PUTNAM'S SONS NEW YORK AND LONDON Cbe Knicftetbocftet press 1911 fe'47708A . A' ;D ,'! ~.*"< " AND TILDl.N' POL ' 3 -P. i-X's I_ • •VV: : • • •••••• Copyright, 1894 BY G. P. PUTNAM'S SONS Entered at Stationers' Hall, London Ube ftntcfeerbocfter press, Hew Iffotfc CONTENTS. PACK PREFACE Xvii INTRODUCTION. THE GREEK AND ARABIC IDEAS OF THE WORLD, AS THE CHIEF INHERITANCE OF THE CHRISTIAN MIDDLE AGES IN GEOGRAPHICAL KNOWLEDGE . I CHAPTER I. EARLY CHRISTIAN PILGRIMS (CIRCA 333-867) . 29 CHAPTER II. VIKINGS OR NORTHMEN (CIRCA 787-1066) . -

Cabeza De Vaca, Estebanico, and the Language of Diversity in Laila Lalami's the Moor's Account

Text Matters: A Journal of Literature, Theory and Culture Number 8 Engaging Ireland / American & Article 19 Canadian Studies October 2018 Cabeza de Vaca, Estebanico, and the Language of Diversity in Laila Lalami’s The Moor’s Account Zbigniew Maszewski University of Łódź Follow this and additional works at: https://digijournals.uni.lodz.pl/textmatters Recommended Citation Maszewski, Zbigniew. "Cabeza de Vaca, Estebanico, and the Language of Diversity in Laila Lalami’s The Moor’s Account." Text Matters: A Journal of Literature, Theory and Culture, no.8, 2020, pp. 320-331, doi:10.1515/texmat-2018-0019 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Arts & Humanities Journals at University of Lodz Research Online. It has been accepted for inclusion in Text Matters: A Journal of Literature, Theory and Culture by an authorized editor of University of Lodz Research Online. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Text Matters, Number 8, 2018 DOI: 10.1515/texmat-2018-0019 Zbigniew Maszewski University of Łódź Cabeza de Vaca, Estebanico, and the Language of Diversity in Laila Lalami’s The Moor’s Account A BSTR A CT Published in 1542, Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca’s La relación is a chronicle of the Pánfilo de Narváez’s 1527 expedition to the New World in which Cabeza de Vaca was one of the four survivors. His account has received considerable attention. It has been appreciated and critically examined as a narrative of conquest and colonization, a work of ethnographic interest, and a text of some literary value. -

Geology of Isla Mona Puerto Rico, and Notes on Age of Mona Passage

Geology of Isla Mona Puerto Rico, and Notes on Age of Mona Passage GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 317-C Prepared in cooperation with the Puerto Rico Water Resources Authority', Puerto Rico Economic Development Administration, Puerto Rico Aqueduct and Sewer Authority, and Puerto Rico Department of the Interior Geology of Isla Mona Puerto Rico, and Notes on Age of Mona Passage By CLIFFORD A. KAYE With a section on THE PETROGRAPHY OF THE PHOSPHORITES By ZALMAN S. ALTSCHULER COASTAL GEOLOGY OF PUERTO RICO GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 317-C Prepared in cooperation with the Puerto Rico Water Resources Authority', Puerto Rico Economic Development Administration^ Puerto Rico Aqueduct and Sewer Authority^ and Puerto Rico Department of the Interior UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1959 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR FRED A. SEATON, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Thomas B. Nolan, Director For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U. S. Government Printing Office Washington 25, D. C. - Price 65 cents (paper cover) CONTENTS Page Page Abstract ----_--__----_-______________ 141 Geology of Isla Mona Continued Geology of Isla Mona_________________ 142 Phosphorite deposits.____________________________ 156 Introduction _____________________ 142 History of mining________-_-_-__-_--.____- 156 Location and topographic description 142 Description of deposits._____________________ 156 Climate _________________________ 143 Petrography of the phosphorites, by Zalman S. Flora and fauna. _________________ 144 Altschuler_______________________________ 157 Faunal origin __ _________________ 145 Analytical data.__-_-----------_1------- 159 History. _ __-----__--__.________ 145 Petrography and origin-_____-___-_---__- 159 Rocks. __________________________ 146 Supplementary nptes on mineralogy of Isla Isla Mona limestone. -

Re-Writing Women's Identities and Experiences in Contemporary

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Research Repository Veiled experiences: re-writing women's identities and experiences in contemporary Muslim fiction in English Firouzeh Ameri B.A. Shahid Beheshti University, Tehran M.A. University of Tehran, Tehran This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of Murdoch University. 2012 i I declare that this thesis is my own account of my research and contains as its main content work which has not previously been submitted for a degree at any tertiary education institution. ii Abstract In dominant contemporary Western representations, including various media texts, popular fiction and life-narratives, both the Islamic faith in general and Muslim women in particular are often vilified and stereotyped. In many such representations Islam is introduced as a backward and violent religion, and Muslim women are represented as either its victims or its fortunate survivors. This trend in the representations of Islam and Muslim women has been markedly intensified following the terrorist attacks of 9/11 2001. This thesis takes a postpositivist realist approach to reading selected contemporary women’s fiction, written in English, and foregrounding the lives and religious identities of Muslim women who are neither victims nor escapees of Islam but willingly committed to their faith. Texts include The Translator (1999) and Minaret (2005) by Leila Aboulela, Does my head look big in this? (2005) by Randa Abdel-Fattah, Sweetness in the belly (2005) by Camilla Gibb and The girl in the tangerine scarf (2006) by Mohja Kahf.