Complete Doc 11 25 14 Formatted

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Casablanca Le, 14 Mai 2010 AVIS N°45/10 RELATIF a L'offre

Casablanca le, 14 mai 2010 AVIS N°45/10 RELATIF A L’OFFRE PUBLIQUE DE RETRAIT EN VUE DE LA RADIATION DE LA SNI A L’INITIATIVE DE COPROPAR, LAFARGE ET DU GROUP INVEST Avis d’approbation de la Bourse de Casablanca n°05/10 du 12 Mai 2010 Visa du CDVM n° VI/EM/010/2010 du 13 Mai 2010 Vu le dahir portant loi n°1-93-211du 21 septembre 1993 modifié et complété par les lois n°34-96, 29- 00, 52-01 et 45-06 relatif à la Bourse des Valeurs, et notamment son article 7 bis, Vu les dispositions de la loi 26/03 relative aux offres publiques sur le marché boursier telle que modifiée et complétée par la loi n° 46-06 et notamment ses articles 6, 20 bis, 21 et 25. Vu les dispositions du Règlement Général de la Bourse des Valeurs, approuvé par l’arrêté du Ministre de l'économie des Finances n°1268-08 du 7 juillet 2008 et notamment ses articles 2.1.1 et 2.2.4. ARTICLE 1 : OBJET DE L’OPERATION Cadre de l’opération - Contexte de l’opération L’offre publique sur les titres de SNI s’inscrit dans le cadre de la réorganisation de l’ensemble SNI/ONA approuvée par les conseils d’administration de SNI et ONA réunis le 25 mars 2010. Cette réorganisation vise la création d’un holding d’investissement unique non coté et ce, à travers le retrait de la cote des deux entités SNI et ONA, suivi de leur fusion. -

Laila Lalami: Narrating North African Migration to Europe

Laila Lalami: Narrating North African Migration to Europe CHRISTIÁN H. RICCI UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, MERCED Introduction aila Lalami, author of three novels—Hope and Other Dangerous Pursuits L(2005), Secret Son (2009), and The Moor’s Account (2014)—and several short stories, has been considered the most important Moroccan author writ- ing in English; her work has been translated into more than eleven languages (Mehta 117). Compelled to write in a language that is not her mother tongue, Lalami’s narrations constitute a form of diasporic writing from within. She succeeds in defying not only the visual and cultural vilification of Muslims, but also the prevailing neo-orientalist concept of Muslim women’s writing as exclusively victim or escapee narratives. Up to now, the focus of most Mo- roccan migration stories “has been on male migrants as individuals, without reference to women, who nowadays constitute about 50% of international migration. This has led to the neglect of women in migration theories” (Ennaji and Sadiqui 8, 14). As the result of labor migration and family reunification (twenty percent of Moroccan citizens now live in Europe), combined with the geo- graphic proximity of Europe and North Africa, the notion of a national or “native” literature is slightly unstable with regard to Morocco. Its literary production is not limited by the borders of the nation-state, but spills over to the European continent, where the largest Moroccan-descent communities are in France (over a million), Spain (800,000), the Netherlands (370,000), and Belgium (200,000). Contemporary Moroccan literature does more than criticize and reb- el against the Makhzen, a term that originally refers to the storehouse where tribute and taxes to the sultan were stowed; through the centuries Makhzen has come to signify not just the power holders in Morocco, but how power has been exercised throughout society. -

Download Book

Arab American Literary Fictions, Cultures, and Politics American Literature Readings in the 21st Century Series Editor: Linda Wagner-Martin American Literature Readings in the 21st Century publishes works by contemporary critics that help shape critical opinion regarding literature of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries in the United States. Published by Palgrave Macmillan Freak Shows in Modern American Imagination: Constructing the Damaged Body from Willa Cather to Truman Capote By Thomas Fahy Arab American Literary Fictions, Cultures, and Politics By Steven Salaita Women and Race in Contemporary U.S. Writing: From Faulkner to Morrison By Kelly Lynch Reames Arab American Literary Fictions, Cultures, and Politics Steven Salaita ARAB AMERICAN LITERARY FICTIONS, CULTURES, AND POLITICS © Steven Salaita, 2007. Softcover reprint of the hardcover 1st edition 2007 978-1-4039-7620-8 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. First published in 2007 by PALGRAVE MACMILLAN™ 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10010 and Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire, England RG21 6XS Companies and representatives throughout the world. PALGRAVE MACMILLAN is the global academic imprint of the Palgrave Macmillan division of St. Martin’s Press, LLC and of Palgrave Macmillan Ltd. Macmillan® is a registered trademark in the United States, United Kingdom and other countries. Palgrave is a registered trademark in the European Union and other countries. ISBN 978-1-349-53687-0 ISBN 978-0-230-60337-0 (eBook) DOI 10.1057/9780230603370 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available from the Library of Congress. -

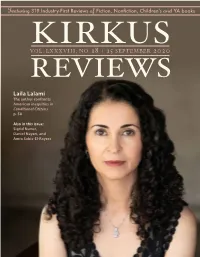

Kirkus Reviews on Our Website by Logging in As a Subscriber

Featuring 319 Industry-First Reviews of Fiction, Nonfiction, Children'sand YA books VOL.KIRKUS LXXXVIII, NO. 18 | 15 SEPTEMBER 2020 REVIEWS Laila Lalami The author confronts American inequities in Conditional Citizens p. 58 Also in this issue: Sigrid Nunez, Daniel Nayeri, and Amra Sabic-El-Rayess from the editor’s desk: The Way I Read Now Chairman BY TOM BEER HERBERT SIMON President & Publisher MARC WINKELMAN John Paraskevas # Among the many changes in my daily life this year—working from home, Chief Executive Officer wearing a mask in public, watching too much TV—my changing read- MEG LABORDE KUEHN ing habits register deeply. For one thing, I read on a Kindle now, with the [email protected] Editor-in-Chief exception of the rare galley sent to me at home and the books I’ve made TOM BEER a point of purchasing from local independent bookstores or ordering on [email protected] Vice President of Marketing Bookshop.org. The Kindle was borrowed—OK, confiscated—from my SARAH KALINA boyfriend at the beginning of the pandemic, when I left dozens of advance [email protected] reader copies behind at the office and accepted the reality that digital gal- Managing/Nonfiction Editor ERIC LIEBETRAU leys would be a practical necessity for the foreseeable future. I can’t say that I [email protected] love reading on my “new” Kindle—I’m still a sucker for physical books after Fiction Editor LAURIE MUCHNICK all these years—but I’ll admit that it fulfills its purpose efficiently. And I do [email protected] Tom Beer rather enjoy the instant gratification of going on NetGalley or Edelweiss Young Readers’ Editor VICKY SMITH and dispatching multiple books to my device in one fell swoop—a harmless [email protected] form of bingeing that affords a little dopamine rush. -

Moroccan Women and Immigration in Spanish Narrative and Film (1995-2008)

University of Kentucky UKnowledge University of Kentucky Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2010 MOROCCAN WOMEN AND IMMIGRATION IN SPANISH NARRATIVE AND FILM (1995-2008) Sandra Stickle Martín University of Kentucky, [email protected] Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Martín, Sandra Stickle, "MOROCCAN WOMEN AND IMMIGRATION IN SPANISH NARRATIVE AND FILM (1995-2008)" (2010). University of Kentucky Doctoral Dissertations. 766. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/gradschool_diss/766 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Kentucky Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION Sandra Stickle Martín The Graduate School University of Kentucky 2010 MOROCCAN WOMEN AND IMMIGRATION IN SPANISH NARRATIVE AND FILM (1995-2008) ___________________________________ ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION ____________________________________ A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of doctor of Philosophy in the College of Arts and Sciences at the University of Kentucky By Sandra Stickle Martín Lexington, Kentucky Director: Dr. Ana Rueda, Professor of Hispanic Studies Lexington, Kentucky 2010 Copyright © Sandra Stickle Martín 2010 ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION MOROCCAN WOMEN AND IMMIGRATION IN SPANISH NARRATIVE AND FILM (1995-2008) Spanish migration narratives and films present a series of conflicting forces: the assumptions of entitlement of both Western and Oriental patriarchal authority, the claims to autonomy and self determination by guardians of women’s rights, the confrontations between advocates of exclusion and hospitality in the host society, and the endeavor of immigrant communities to maintain traditions while they integrate into Spanish society. -

L'ambitiond'andre Azoulay Sanbar, Le Responsable De

Quand leMaroc sera islamiste Lacorruption, unsport national L'ambitiond'Andre Azoulay I'Equipement et wali de Marrakech, qui sera nomme en 200S wali de Tanger; le polytechnicien Driss Benhima, fils Durant les deux dernieres annees du regne d'Hassan II, d'un ancien Premier ministre et ministre de I'Interieur ; un vent reformateur va souffler pendant quelques mois au Mourad Cherif, qui fut plusieurs fois ministre et dirigea Maroc. Un des principaux artisans de cette volonte de tour atour l'Omnium nord-africain puis l'Office cherifien changement aura ete Andre Azoulay, le premier juif maro des phosphates - les deux neurons economiques du cain aetre nomme conseiller de SaMajeste par dahir (decret royaume -, avant d'etre nomme en mars 2006 ala tete de royal). Le parcours militant de ce Franco-Marocain, un la filiale de BNPParibas au Maroc, la BMCI ; et enfin Hassan ancien de Paribas et d'Eurocom, temoigne d'un incontes Abouyoub, plusieurs fois ministre et ancien ambassadeur. table esprit d'ouverture. Artisan constant d'un rapproche Ainsi Andre Azoulay pretendait, avec une telle garde ment [udeo-arabe, il cree en 1973 l'association Identite et rapprochee, aider le roi Hassan II dans ses velleites Dialogue alors qu'il reside encore en France. Aidepar Albert reformatrices. Sasson, un ancien doyen de la faculte de Rabat fort res Seulement, l'essai n'a pas ete transforme. Dans un pre pecte, Andre Azoulay organise de multiples rencontres mier temps, l'incontestable ouverture politique du entre juifs et Arabes.Sesliens d'amitie avec Issam Sartaoui, royaume, qui a vu Hassan II nommer ala tete du gouverne Ie responsable de l'OLP assassine en 1983, ou avec Elias ment le leader socialiste de l'USFP, s'est accompagnee d'un Sanbar, le responsable de la Revue d'etudes palestiniennes, processus d'assainissement economique. -

CONSEIL D'administration DU 17 Mars 2021

CONSEIL D’ADMINISTRATION DU 17 Mars 2021 RAPPORT DU CONSEIL D’ADMINISTRATION SUR LES OPERATIONS DE L’EXERCICE 2020 A L’ASSEMBLEE GENERALE ORDINAIRE ANNUELLE Messieurs les Actionnaires, Nous vous avons réuni en Assemblée Générale Ordinaire Annuelle, conformément à la loi et à l’article 22 des statuts, pour entendre le rapport du Conseil d’Administration et celui des Commissaires aux Comptes sur l’exercice clos le 31 décembre 2020. Avant d’analyser l’activité de la Compagnie, nous voudrions vous rappeler brièvement l’environnement économique international et national dans lequel elle a évolué ainsi que le contexte du secteur des assurances. CONTEXTE A l’international Dans un contexte de crise inédit, l’économie mondiale a connu une sévère récession en 2020 (- 3,7% selon la Banque Mondiale), frappée de plein fouet par la pandémie du COVID-19. Confrontée à une grave crise sanitaire (plus de 28,6 millions de cas au 28/02/2021), l’économie américaine a perdu 3,6% en 2020, la pire récession depuis 1946, affectée par les effets de la pandémie. Après une forte remontée du PIB au 3ème trimestre 2020 (+33,1% en glissement annuel), la reprise s’est affaiblie au 4ème trimestre 2020 suite à la résurgence des infections au Coronavirus et la mise en place de nouvelles restrictions locales. Pour sa part, la croissance en Zone Euro accuse un repli historique de 6,8% en 2020 en raison de l’aggravation de la situation sanitaire et la multiplication des mesures de confinement dans la plupart des grandes économies de la Zone. Le recul le plus marqué est en Espagne (-11%) contre -8,8% pour l’Italie, -8,3% pour la France et -5% pour l’Allemagne. -

Expat Guide to Casablanca

EXPAT GUIDE TO CASABLANCA SEPTEMBER 2020 SUMMARY INTRODUCTION TO THE KINGDOM OF MOROCCO 7 ENTRY, STAY AND RESIDENCE IN MOROCCO 13 LIVING IN CASABLANCA 19 CASABLANCA NEIGHBOURHOODS 20 RENTING YOUR PLACE 24 GENERAL SERVICES 25 PUBLIC TRANSPORTATION 26 STUDYING IN CASABLANCA 28 EXPAT COMMUNITIES 30 GROCERIES AND FOOD SUPPLIES 31 SHOPPING IN CASABLANCA 32 LEISURE AND WELL-BEING 34 AMUSEMENT PARKS 36 SPORT IN CASABLANCA 37 BEAUTY SALONS AND SPA 38 NIGHT LIFE, RESTAURANTS AND CAFÉS 39 ART, CINEMAS AND THATERS 40 MEDICAL TREATMENT 45 GENERAL MEDICAL NEEDS 46 MEDICAL EMERGENCY 46 PHARMACIES 46 DRIVING IN CASABLANCA 48 DRIVING LICENSE 48 CAR YOU BROUGHT FROM ABROAD 50 DRIVING LAW HIGHLIGHTS 51 CASABLANCA FINANCE CITY 53 WORKING IN CASABLANCA 59 LOCAL BANK ACCOUNTS 65 MOVING TO/WITHIN CASABLANCA 69 TRAVEL WITHIN MOROCCO 75 6 7 INTRODUCTION TO THE KINGDOM OF MOROCCO INTRODUCTION TO THE KINGDOM OF MOROCCO TO INTRODUCTION 8 9 THE KINGDOM MOROCCO Morocco is one of the oldest states in the world, dating back to the 8th RELIGION AND LANGUAGE century; The Arabs called Morocco Al-Maghreb because of its location in the Islam is the religion of the State with more than far west of the Arab world, in Africa; Al-Maghreb Al-Akssa means the Farthest 99% being Muslims. There are also Christian and west. Jewish minorities who are well integrated. Under The word “Morocco” derives from the Berber “Amerruk/Amurakuc” which is its constitution, Morocco guarantees freedom of the original name of “Marrakech”. Amerruk or Amurakuc means the land of relegion. God or sacred land in Berber. -

2016 Retail Foods Morocco

THIS REPORT CONTAINS ASSESSMENTS OF COMMODITY AND TRADE ISSUES MADE BY USDA STAFF AND NOT NECESSARILY STATEMENTS OF OFFICIAL U.S. GOVERNMENT POLICY Required Report - public distribution Date: 12/30/2016 GAIN Report Number: MO1621 Morocco Retail Foods 2016 Approved By: Morgan Haas Agricultural Attaché Prepared By: Mohamed Fardaoussi, Agricultural Specialist Report Highlights: This report provides U.S. exporters of consumer-ready food products with an overview of the Moroccan retail foods sector. Best product prospects are included in this report. Best prospects for U.S. products are dried fruits and nuts (pistachios, walnuts, non-pitted prunes, raisins, and almonds), dairy (milk powder, whey, cheese, butter), confectionary items and frozen seafood. In 2015, U.S. exports of consumer-oriented product to Morocco were valued at $24 million. Table of Contents SECTION I. MARKET SUMMARY ........................................................................................................ 4 Major Categories of Supermarkets ..................................................................................................... 4 Trends in Distribution Channels ......................................................................................................... 4 Trends in Services Offered by Retailers ............................................................................................. 6 SECTION II: ROAD MAP FOR MARKET ENTRY ............................................................................... 8 A1. Large Retail and Wholesale -

The Role of Academia in Promoting Gender and Women’S Rights in the Arab World and the European Region

THE ROLE OF ACADEMIA IN PROMOTING GENDER AND WOMEN’S RIGHTS IN THE ARAB WORLD AND THE EUROPEAN REGION Erasmus+ project “Gender Studies Curriculum: A Step for Democracy and Peace in EU- Neighboring Countries with Different Traditions”, No. 561785-EPP-1-2015-1-LT-EPPKA2-CBHE-JP UDC 305(063) Dépôt Légal : 2019MO2902 ISBN : 978-9954-692-05-9 The Role Of Academia In Promoting Gender And Women’s Rights In The Arab World And The European Region // Edited by Souad Slaoui, Khalid Bekkaoui, Kebir Sandy, Sadik Rddad, Karima Belghiti. – Publ. Société Généraled’Equipement&d’impression, Fes, Morocco, 2019. – 382 pp. This book contains articles by participants in the Forum " The role of academia in promoting gender and women’s rights in the Arab world and the European region " (Morocco, Fez, October, 1- 5, 2018 ). In the articles, the actual problems of gender identity, gender equality, gender education, gender and politics, gender and religion are raised. The materials will be useful to researchers, scientists, graduate students and students dealing with the problems of gender equality, intersexual relations, statistical indices of gender equality and other aspects of this field. Technical Editors: Natalija Mažeikienė, Olga Avramenko, Volodymyr Naradovyi. Acknowedgements to PhD students Mrs.Hajar Brgharbi, Mr.Mouhssine El Hajjami who have extensively worked with editors on collecting the abstract and the paper at the first stage of the compilation of this Conference volume. Recommended for publication: Moroccan Cultural Studies Centre, University SIdi Mohammed Ben Abdallah, Faculty of Letters and Human Sciences Dhar Al Mahraz, Fez. ERASMUS+ Project “Gender Studies Curriculum: A Step for Democracy and Peace in EU- neighboring countries with different traditions – GeSt” [Ref. -

14Th Annual Global Women's Rights Forum

Program of the 14th Annual Global Women’s Rights Forum Wednesday, March 4, 2015 Feminist Art in Movement: The Sarah Bush Dance Project 6:00-8:00 p.m., McLaren Conference Center 250 & 251 *Reception at 6:00 p.m., Performance at 6:30 p.m.* The Sarah Bush Dance Project (SBDP) is a contemporary dance company based in Oakland. Led by Artistic Director Sarah Bush, SBDP has brought Urban Contemporary dance to venues throughout the Bay Area since 1999. Sarah Bush creates dances that show strong, emotional, well-rounded women — dances that inspire all women to feel better about our place in the world. The company explores issues of identity, gender, and sexuality within the broader themes of love, relationships, loss, power and empowerment. Thursday, March 5, 2015 Engendering Immigration Justice 6:30-8:00 p.m., Fromm Hall, Maier Room This evening will focus on the ways in which immigration policies at the international, national, and local levels are affected by gender and other intersecting relations of power, and show how women are organizing to achieve a more just and humane immigration politics. Panelists: Maylei Blackwell Professor Maylei Blackwell is an interdisciplinary scholar activist, oral historian, and author of ¡Chicana Power! Contested Histories of Feminism in the Chicano Movement, published with University of Texas Press. She is an Assistant Professor in the César E. Chávez Department of Chicana/o Studies and Women's Studies Department, and affiliated faculty in the American Indian Studies and Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Studies. Her research has two distinct, but interrelated trajectories that broadly analyze how women's social movements in the U.S. -

2014 Annual Report

2014 ANNUAL REPORT 0 1 9 4 - 2 0 1 years 4 2014 ANNUAL REPORT 0 1 9 4 - 2 0 1 years 4 This is a particularly important year for Attijariwafa bank as we complete our one hundred and tenth year. We are therefore celebrating more than a century of providing banking and banking- related activities in the interests of our country’s economic and industrial development and the well- being of our fellow citizens. M. Mohamed El Kettani Président Directeur Général Chairman and CEO’S Message ANNUAL REPORT ATTIJARIWAFA BANK 2014 Our Group’s history is inextricably intertwined with With the legacy of two century-old banks, that of the Kingdom of Morocco. Not only does that Attijariwafa bank has constantly sought to diversify make us proud, it constantly inspires us to scale even its business lines to provide its corporate customers greater heights. Attijariwafa bank’s history began when with the most sophisticated payment methods two French banks, Compagnie Algérienne de Crédit and financing products to satisfy their constantly et de Banque (CACB) and Banque Transatlantique, evolving requirements. Our Group is also committed to opened branches in Tangier in 1904 and 1911 meeting the needs of all our fellow citizens, whatever respectively. their socio-economic background. For this reason, In the aftermath of the independence, Banque Attijariwafa bank was the first bank to make the Transatlantique became Banque Commerciale financial inclusion of low-income households one du Maroc (BCM) and, in 1987, emerged as the of its strategic priorities. Attijariwafa bank is proud of Kingdom’s leading private sector bank.